This is the latest in a series of posts that publish for the first time significant documents related to the Polar Controversy.

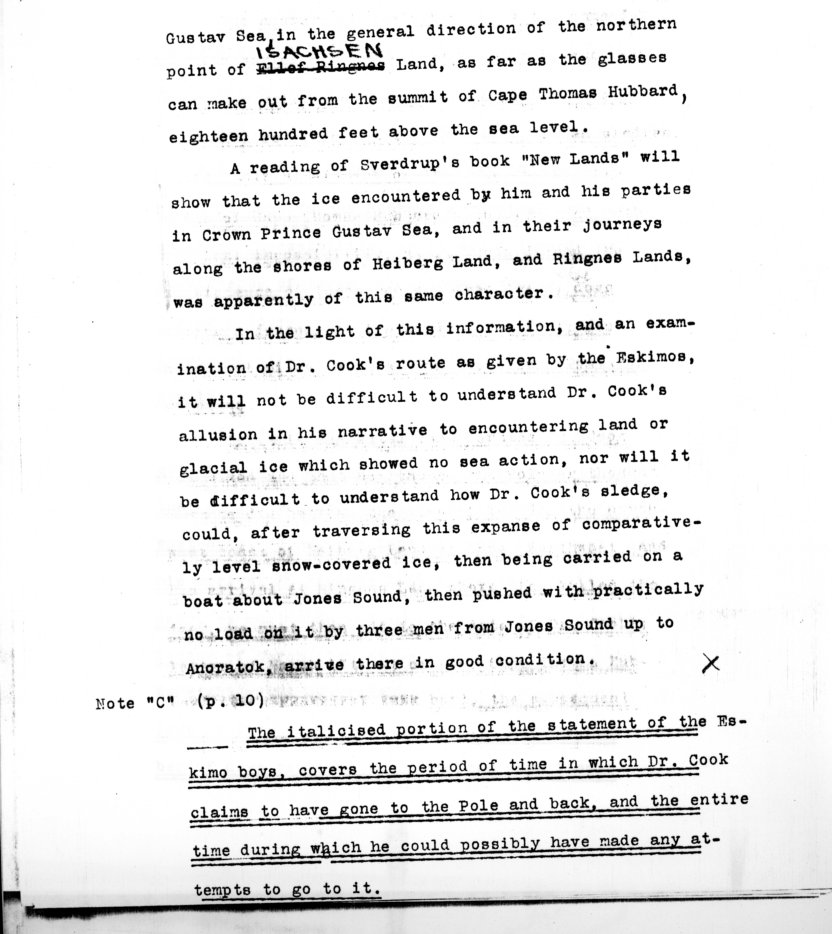

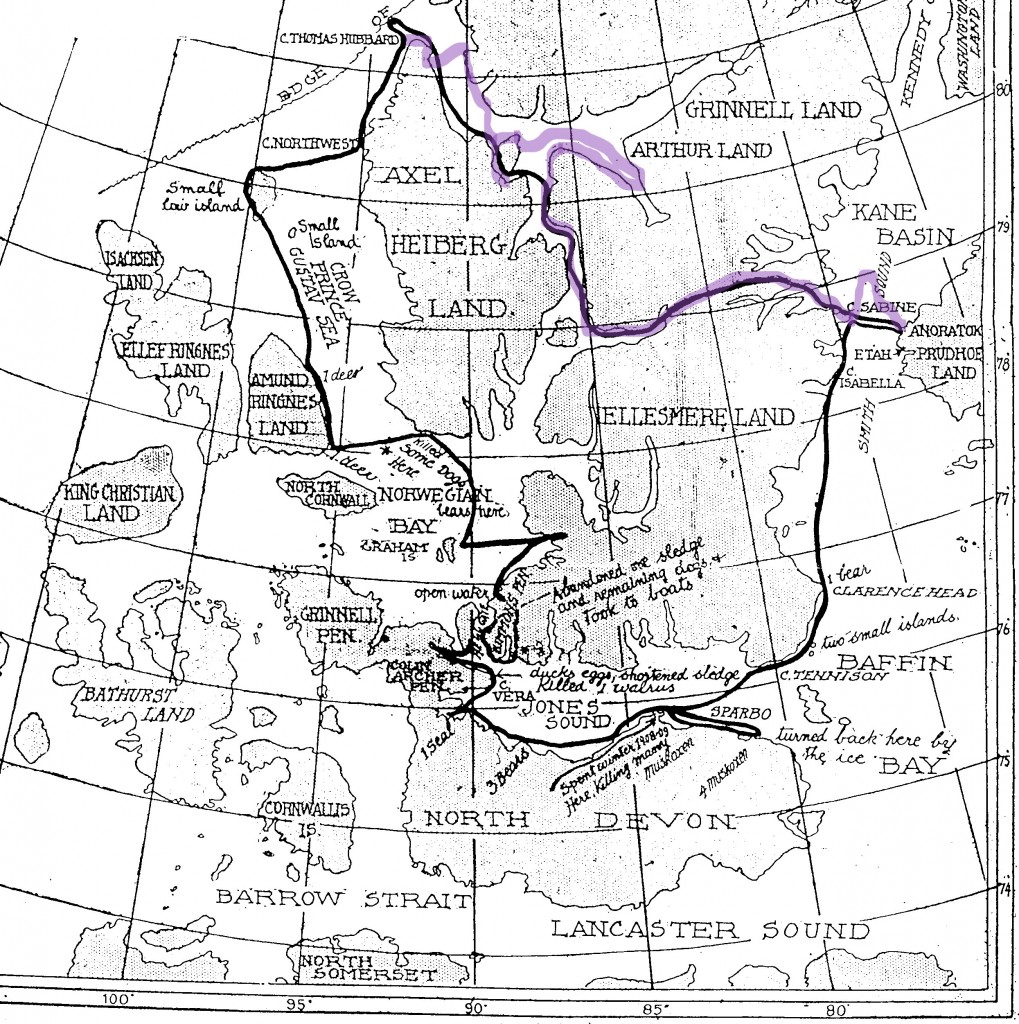

We have now come to the penultimate installment of this series, having examined the first leg of Cook’s journey from Annoatok to Cape Thomas Hubbard and the third leg of his journey from his return to land until he again reached Annoatok. We have seen that as far as the first leg is concerned, when compared to documentary evidence, Peary’s alleged Inuit account is demonstrably incorrect in many crucial respects, whereas in the case of the third leg, compared to more limited documentary but significant circumstantial evidence, Peary’s statement is borne out to a much larger extent than the route claimed by Dr. Cook. Between these two legs lies a gap covering the period Cook was out on the sea ice north of his starting place at the tip of Axel Heiberg Island.

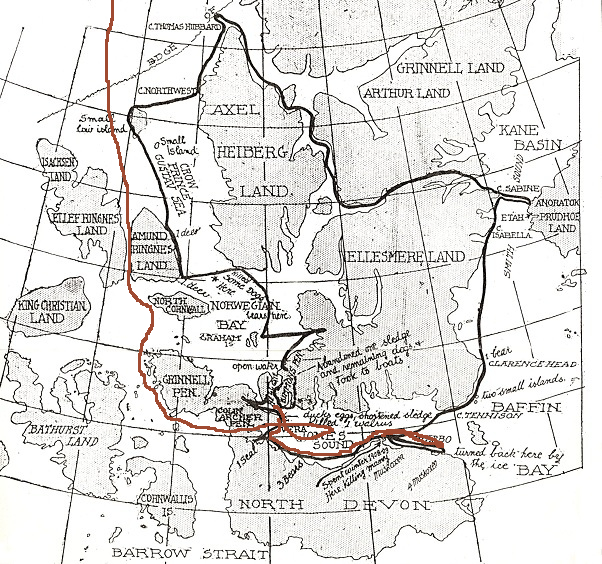

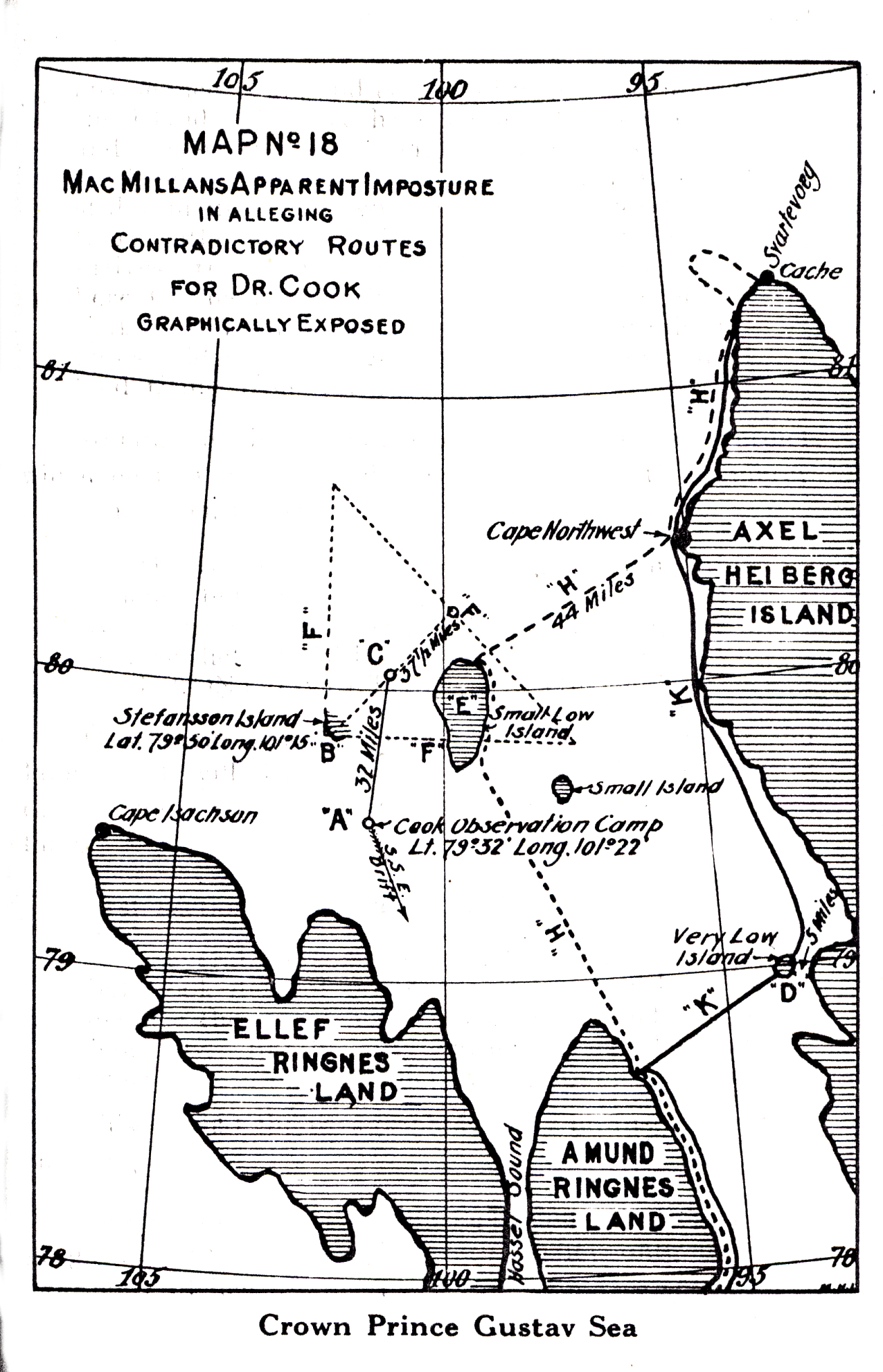

There is no question that Cook left land. Every witness, and even Peary, conceded that. The only questions to be settled are in what direction he went, how long he remained away from land, and how far he traveled during that time. The first of these is easily dispatched: when he left land he went to the northwest, not due north. Cook, himself, and every account that touches on this part of his journey, including Peary’s, are consistent on this point. But why?

It appears that he took this direction for several reasons. As his erroneous celestial observation sights published in My Attainment of the Pole prove, and all other relevant evidence, including his conversation with Alfred de Quervain show (see Part 6 of this series) Cook never mastered the navigational skills necessary to find the North Pole, including the use of a sextant. This seems incredible, but is evidently true, nonetheless.

He was an avid reader of anything that had to do with the polar regions, collected everything published on the subject, and even had those articles bound into books for future reference. Cook, who was described by one associate as “ingenious and impractical,” said that in these readings he had found a simple way to reach the North Pole by compass alone. After studying the data published by Nansen and Sverdrup, he surmised that near the 97th parallel there was what he termed a “magnetic meridian” (actually an isogonic line) where the needle of a magnetic compass would point 180° out of true. In other words, once on this “magnetic meridian,” the compass’s needle, instead of pointing due North, would point due South, enabling him to reach the North Pole by following his compass due South, dispensing with the need to take celestial observations with a sextant. Or so he thought.

This was an idea Cook believed the rest of his life, even mentioning it in the “Author’s Note” to his posthumous book, Return from the Pole, written in the 1930s. But it was not that simple, though Cook never understood why, because once reached, it would have been impossible to stay on his “magnetic meridian” without frequent checks of his position via a sextant. That isogonic line, if not on the 97th parallel, did lie somewhere to the northwest of Cook’s starting point. But another reason he might have chosen such a course also came from his extensive study of polar-related scientific literature.

At the time of Cook’s expedition, a large part of the Arctic basin had never been explored. There was a strong belief in some scientific circles, based on observations of natural phenomena in the high arctic, that there lay in that unexplored region above Canada and Alaska undiscovered land or possibly even an “unknown continent.” Through his reading, Cook absorbed this belief. As early as 1900 he wrote: “It seems reasonable to expect some rocky islets north of Greenland as far as the 85th parallel, surely to the 84th. If stations were placed here there would be only 360 miles to cover [to reach the pole].” Up to the moment he left Annoatok, he had this idea in mind. Before he departed, he left two letters (both dated February 20, 1908—the day after he later said he left for the pole!), one addressed to Knud Rasmussen and the other “To whom it may concern.” The one to Rasmussen mentioned that “There is also a strong possibility of our finding much land to the westward of Crocker Land,” and that he might return via them to Alaska instead of Greenland. If he could go far enough to make such a discovery in the area that many scientists believed already held unknown land, it would be a major scientific result of his expedition and also might serve as a way station to replenish supplies on his return journey from the North Pole or act as a stepping stone for some future attempt to reach it. And if an actual “unknown continent” existed, it might mitigate the generally easterly drift reported by earlier explorers, and possibly also shield his route from the extreme disruptions to the pack ice experienced by others who had tried to approach the pole from routes much farther east, including Peary’s 1906 attempt, on which he was nearly swept past the top of Greenland and out to sea. Peary’s report after that expedition that he had sighted from the heights of Cape Thomas Hubbard a new land lying about 120 miles northwest, which me called “Crocker Land,” only strengthened Cook’s belief that a course to the northwest would have many practical advantages.

We have it from Cook that the two additional natives accompanied him for three full days, but did not sleep at their camp at the end of the third day, but instead started for home. Peary’s statement is incorrect on this point, because it is confirmed by one of those Inuit, Inughito, in the notes taken down by George Borup (see Part 4 of this series). One of the many oddities of My Attainment of the Pole is that Cook doesn’t mention taking the two extra natives until after he has already gone two days from land. He does claim, however that he made two of his longest marches with their assistance.

Although MacMillan’s later accounts differ in detail from that which Peary published, he signed his name to Peary’s as a true account of what Cook’s Inuit said in 1909. So if we consider Peary’s published account the first account they gave him, and the one closest to the events being described, this contradictory evidence demands a careful reading of the rest of it, similar to that done by Captain Hall (see Part 10). Peary’s published account, although it does not say so explicitly, as Captain Hall discovered, implies Cook traveled at least four days on the ice away from land in addition to whatever time it took to return, and indeed, its vague language does not rule out an even longer stay on the ice than that. However, how far he actually traveled is difficult to determine because there is no consistent evidence in any of the subsequent reported accounts of what Cook’s Inuit companions said except that all of them claim the Inuit said they were never out of sight of land.

Of course, Cook himself said he left land on March 18 and traveled all the way to the North Pole and back between that date and June 13. So, let us be clear on this point from the very start: although how far he traveled is uncertain, Frederick Cook did not reach the North Pole. This was not, however, because, as Peary implied, he had inadequate equipment or supplies to do so, but because by the time he reached his jumping off place he had already run out of the most important commodity of all on such a trip: Time itself.

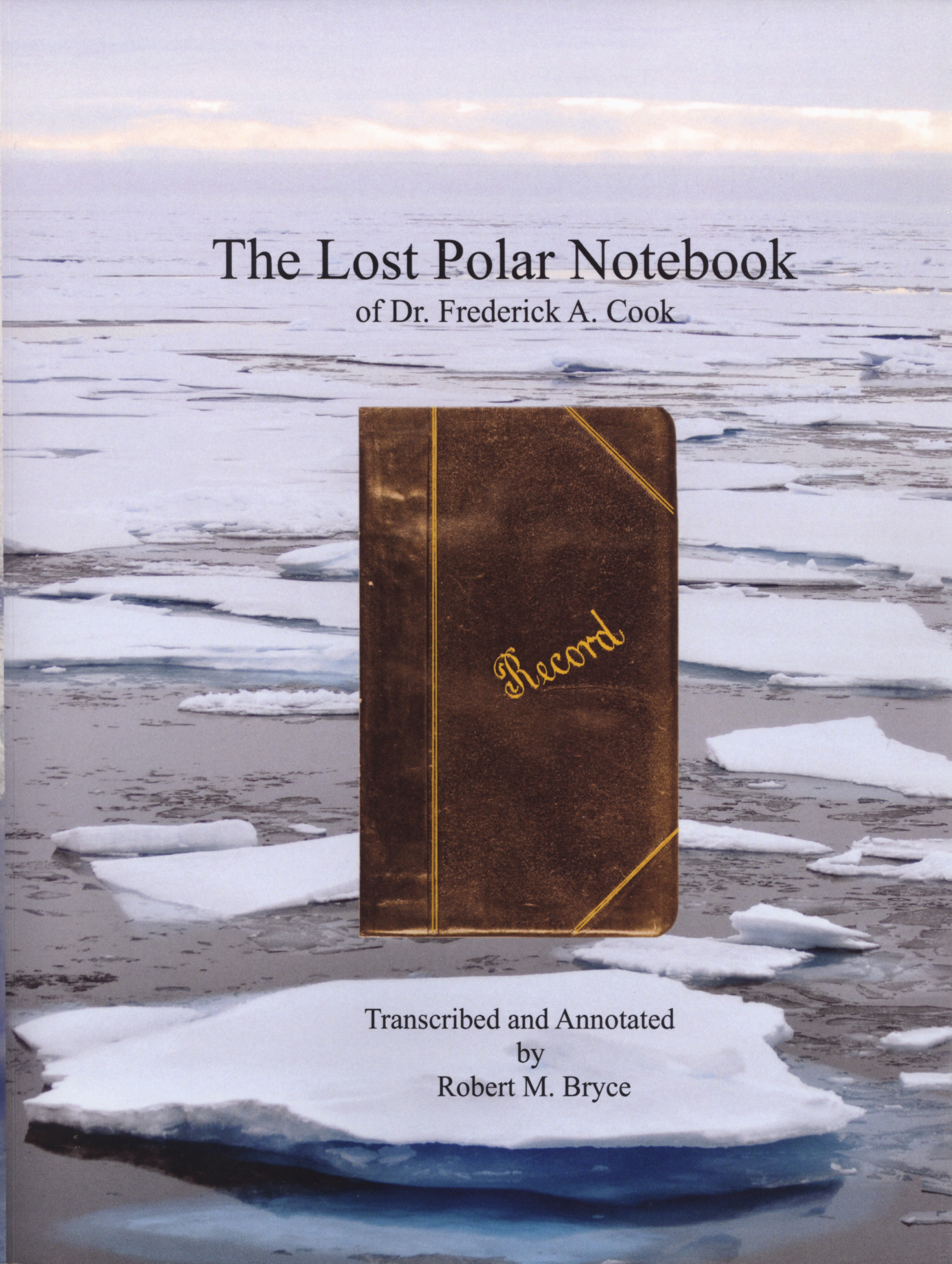

A careful analytical study of his original field diary kept on the first leg of his journey which I recovered from Denmark in 1994 (see the author’s The Lost Arctic Notebook of Dr. Frederick A. Cook), and the account written by Rudolf Franke, Cook’s only civilized companion over the winter, shows that he left Annoatok, not on February 19 as he claimed, but a week later, and that he was delayed en route to the extent that he did not reach Cape Thomas Hubbard until about April 13. Cook knew starting for the pole that late would be untenable with the advance of the season, and his claim to have attained it on April 21, just 8 days after he left land, would be, of course, impossible. His delays en route were not due to poor planning, however.

The diary he kept over his winter at Annoatok, now at the Library of Congress, shows that he fully intended to make an actual attempt to reach the pole. Many of his preparations show that he had been theorizing this attempt for years, had made careful and practical plans for his attempt, had adequate equipment and supplies, and strongly refutes any argument that his expedition was some sham from the beginning designed to cover up an already premeditated plan to make a fraudulent claim of success. Although he left a week later than he claimed in My Attainment of the Pole, his diary indicates that he nevertheless left at the earliest possible time that he could, considering weather conditions and logistical necessities. Likewise, his tardy arrival at his place of departure from land was not due to poor planning, either, but instead to two uncontrollable factors: the actual physical conditions he encountered en route, and the fact that he was traveling with a large group of Inuit.

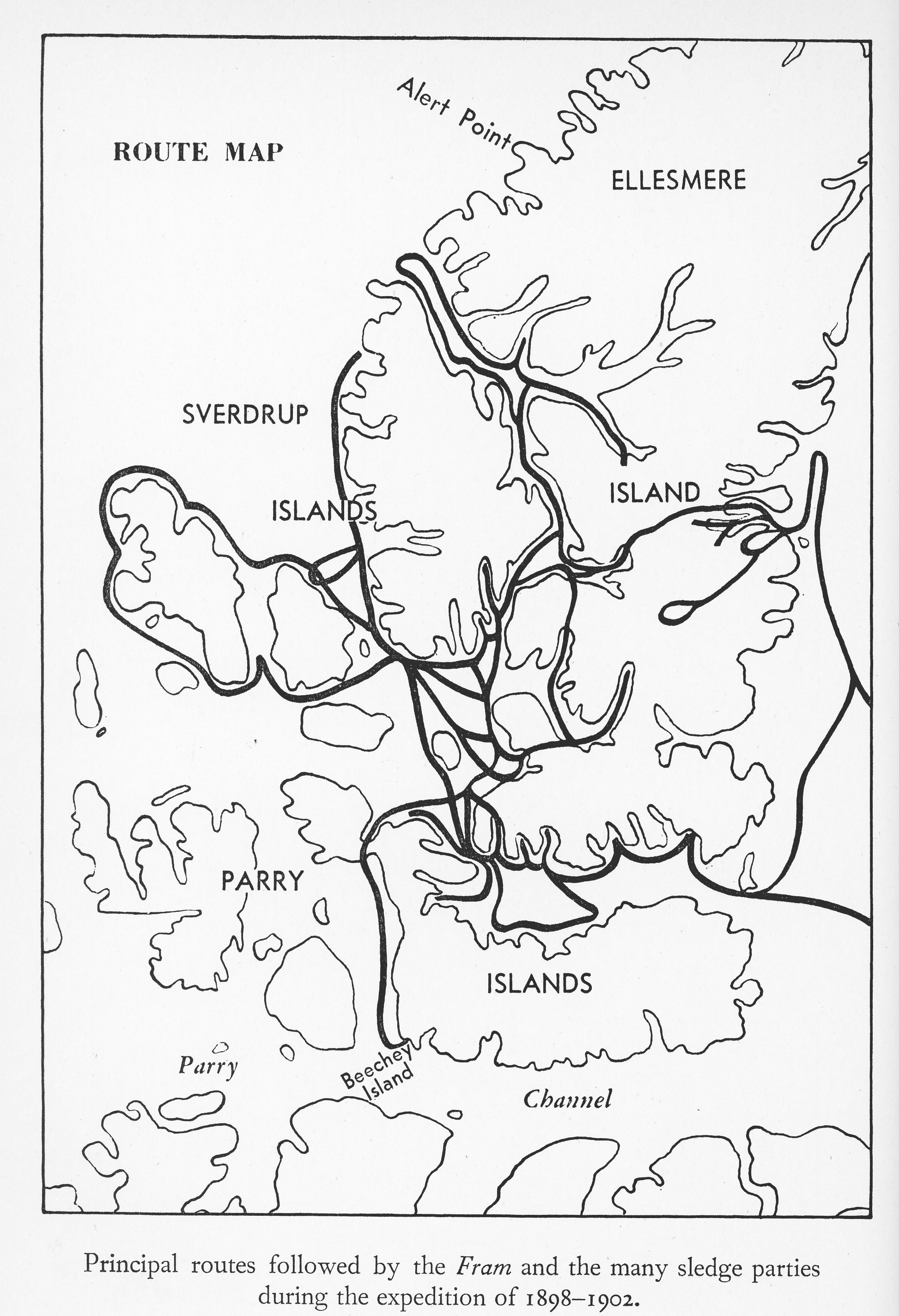

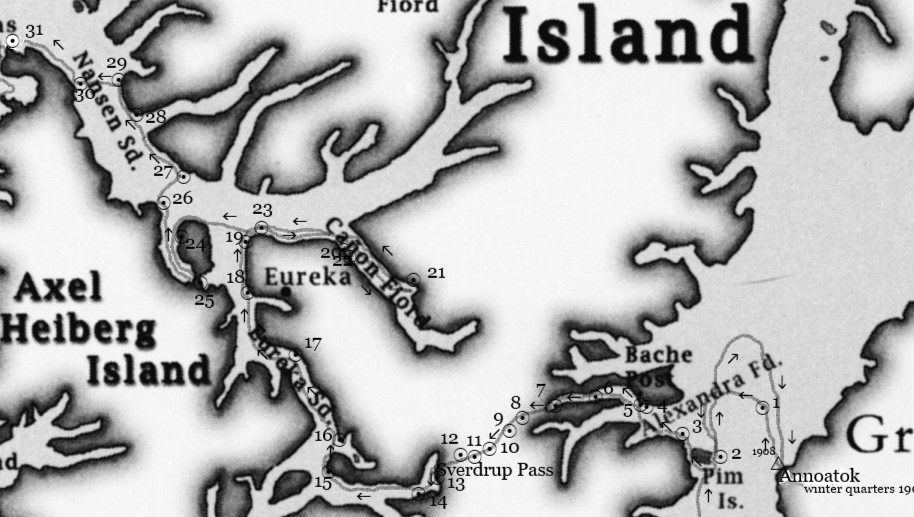

Cook had studied Sverdrup’s book, New Land, in detail, and hoped to shortcut Sverdrup’s route to Nansen Sound by reaching the icecap of Elllesmere Island, and from there descending into Cannon Fjord. Unable to do this, he was forced to follow Sverdrup’s route and encountered all the same impediments Sverdrup had described in his crossing Ellesmere to Bay Fjord in 1899: little snow cover on the pass, and a glacier that blocked access to the route of descent into the fjord. He was delayed five days by the glacier alone. But his Inuit companions were his major source of delay. Although they were indispensable to Cook in getting him safely to his jumping off point, Inuit in those days could not be hurried. They had no concept of such things as “deadlines,” or such abstractions as “the North Pole” and the time limits on when a successful trip had to begin for one to reach it and return alive again.

As far back as Charles Francis Hall, who in the 1860s was the first explorer to adopt Inuit culture and travel with them, explorers were frustrated by their inability to impress Inuit with such abstract goals as they were pursuing. They were slowed by the Inuit propensity to keep to no time schedule, and were thus forced to travel instead at the Inuit’s own pace. As Wally Herbert found out by his experiences with Inuit in the mid-1960s, little had changed since Hall’s time: “Unlike most Europeans, they do not regard the Arctic as a setting in which to test themselves, they are the Inuit, the real men, and never in a hurry.” But Cook was in a hurry.

He knew that to have any realistic chance of reaching the North Pole every day counted. He had estimated a round trip of 80 days from Cape Thomas Hubbard, so he had no time to lose to begin his journey at the earliest possible moment. But his Inuit were not explorers; they were hunters, first and foremost, and whenever game was encountered they slaughtered it. After slaughtering it they dressed it carefully and cached what they and their dogs did not eat for future reference. These procedures took time—in the case of musk oxen kill, a full day or more. As they encountered herds of these animals as well as polar bears along their route to land’s end, they thus moved at the Inuit hunter’s unhurried, age-old pace. This caused Cook’s time schedule to continue to slip, so much so, that by the time he reached halfway up Eureka Sound he knew he would arrive too late at the shore of the Arctic Ocean to have any reasonable chance of reaching the pole.

Cook’s detour into Greely and Cannon Fjords to lay caches for his return to Greenland, instead of taking the direct route up Nansen Sound Peary mistakenly attributed to him on his map, were errands no explorer bent on reaching the pole would have gone on, and they show that it is very likely that by that point, Cook was at least considering a false claim to have reached the North Pole.

With the pole out of the picture, two questions still remain: how long and how far did Cook travel on the sea ice after leaving land, and why, if he knew he had no chance of success at the pole, did he hazard any journey away from land at all? The first question has at least some evidence we can consider; the second is one that can be only speculated on, given our knowledge of subsequent events. But it must be stated right here, before beginning, that the answer to either question cannot be given with a great degree of certainty. The answers proposed here are therefore the author’s considered opinions only, not statements of fact, because as we stated at the very outset of this series, it is impossible to “prove” an unwitnessed assertion, which is what Cook’s claim of polar attainment is. But every opinion given here is based on evidence, nonetheless. So, let’s consider the evidence bearing on the first question, first.

As we have seen (Part 13 of this series) the Inuit story about their journey with Cook changed. At first, anyone who heard Inuit gossip along the Greenland coast in 1909 from Nerke to Umanaq Fjord, consistently and without exception heard that Daagtikoorsuaq and two Inuit had reached the North Pole. That changed when Peary arrived there in August. Then the consistent story became that they had not been out of sight of land, and, therefore, Cook could not have reached the pole, which lay hundreds of miles from any known coast. That change came when Etukishuk and Ahwelah realized “what Peary’s men wanted them to say.” Henson, their interrogator himself, confirmed this: “[Dr. Cook] ordered [his Inuit] to say that they had been at the North Pole, [but] after I questioned them over and over again they confessed that they had not gone beyond the land ice.”

But the change of their story may actually represent something else, besides “ilira.” They at first probably believed that they had reached the North Pole because Cook had told them so. Why would he have turned back if he hadn’t? Furthermore, according to Rasmussen, Cook had shown signs of elation and “jumped and danced like an Angekok when he had looked at his sun glass and saw that they were only one day’s journey from the Great Nail.” (as quoted in “The Witnesses for Dr. Cook,” by the then United States Minister to Denmark, Maurice Francis Egan, which appeared in The Rosary, v. xxxv, no. 5 (November 1909)). After camping there several days he started back voluntarily, although there was “no need to turn back because the ice was good.” They understood generally that the North Pole lay out over the ice to the North, but not just how far, and Cook had gone an entirely different direction than Peary to get there.

Harry Whitney, who lived and traveled with the Polar Inuit a year, has many insightful and sympathetic things to say about them and their culture in his book, Hunting with the Eskimos. Whitney noted that Inuit, although they had a good sense of direction, were not good at judging distances, and in the light of the never-setting summer sun, divided periods of effort into “sleeps” instead of days:

“Four “sleeps” indicated nothing. It might have meant two hundred miles, or it

might have meant 50 miles. The Eskimo has no conception of distance. He is

endowed with certain artistic instincts which enable him to draw a fairly accurate map

of a coast line with which he is thoroughly familiar, but he cannot tell you, even

approximately, how far it is from one point to another. Often when they told me a

place we were bound for was very close at hand, it developed that we were far from it.

This is something they are never sure of and cannot indicate.”

Cook certainly knew this, so he knew that the Inuit had no conception of the distance to the North Pole. Abstractions like the North Pole meant nothing to them anyway, so they had no interest in the place themselves and were not eager to go far from land in any case. They probably begged Cook to return, as Pewahto would MacMillan in 1914. They would be satisfied by Cook’s mere statement that the goal had been reached, and then would happily return to the safety of land and to their families on home shores, where they would collect their pay. In 1909, Ahwelah and Etukishuk shared with other Inuit Cook’s statement to them that they had reached the “Big Navel,” but in 1914, when MacMillan had shown them on the map in My Attainment of the Pole where Cook said he had gone with them to reach it, they had a good laugh over it. Even with “no conception of distance,” they could see they had not traveled that far north. After that, the Inuit nicknamed Cook “The Big Liar.”

Peary’s statement does not attribute any estimate of the distance they went form shore at all. There were some later estimates given, ranging from 12-25 miles, but Peary’s statement only said they were never out of sight of land. Of course, this precludes that Cook actually reached the pole, but we have already ruled out that possibility by documentary evidence. If the Inuit told the truth, how far could Cook have gone and still not have been “out of sight of land”? For a definite answer to this question we must turn forward five years to MacMillan’s experiences on his attempt to reach Crocker Land in 1914 (see Part 6).

In his 1914 letter to Brainerd, MacMillan states that he lost sight of Grant Land at about 75 miles from shore, and in his book, Four Years in the White North, he said it was 78. In his original diary, now at the American Museum of Natural History, he says he was at this position on his sixth day of travel. He also states there that the next morning he thought he saw land in the morning to the west, but it proved to be only a mirage. After going on two more days he was stopped by chaotic ice. At that point MacMillan placed his party’s position at 106 miles northwest of their starting point by dead reckoning (DR), but a celestial observation gave their position as 82° 11’ N, 120 miles from shore. (In his book, MacMillan says this observed position “agreed almost exactly with out dead-reckoning,” but this is not true. Other details in his book are also at variance with his original diary.) They then attempted to go on the next day, but the ice was so impossible they made only a few miles before giving up, because they were already beyond the supposed position of Crocker Land and nothing was in sight. They had been on the ice 8 days at this point and had averaged about 15 a day by observation, not counting their last few futile miles. [all mileage figures are in Nautical Miles, 60 of which equal one degree of latitude]. However, when MacMillan published his book about the Crocker Land Expedition, he claimed his traveling companion, Ensign Green, had “recomputed” their position at the time they turned back and found that instead of 120 miles, they were actually 150 miles away from their starting point. That ups the mileage to 18.75 miles per day.

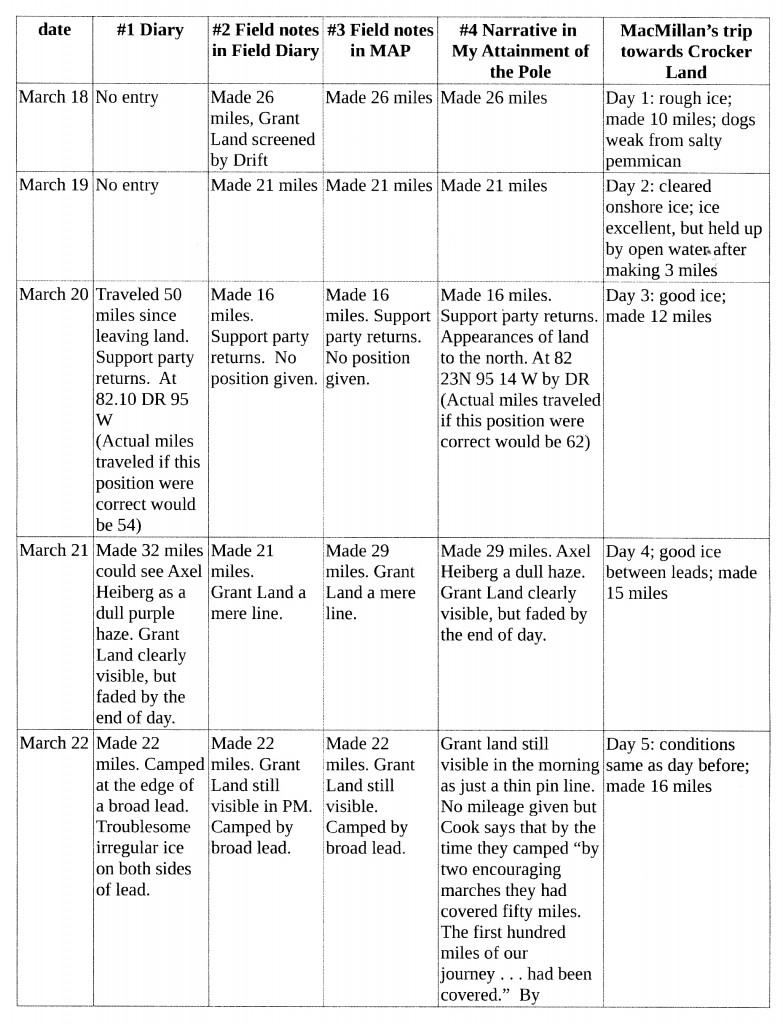

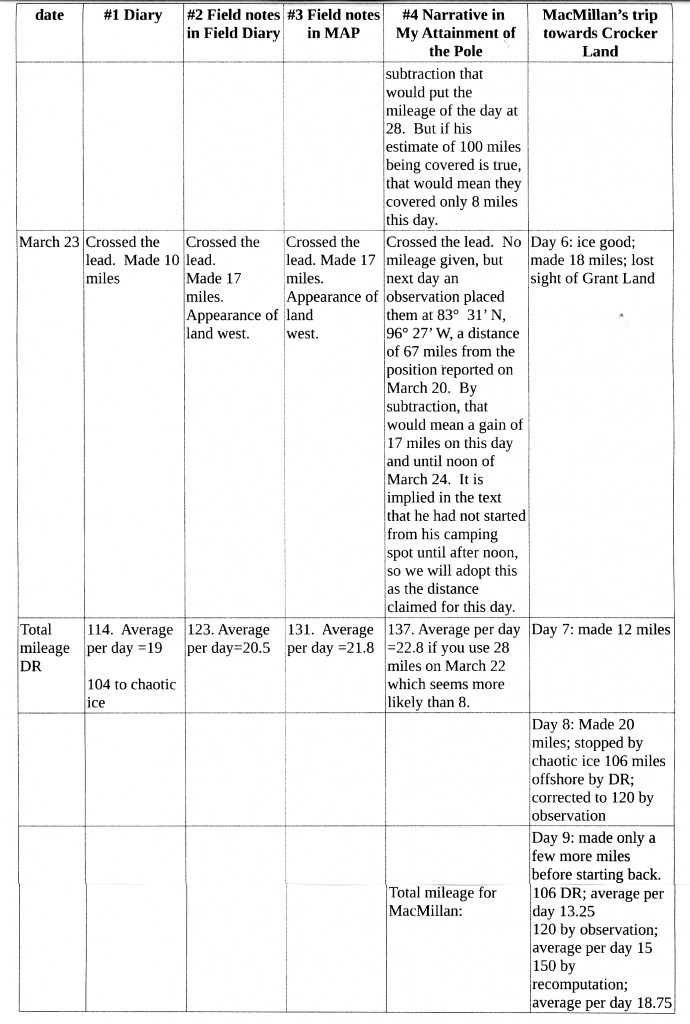

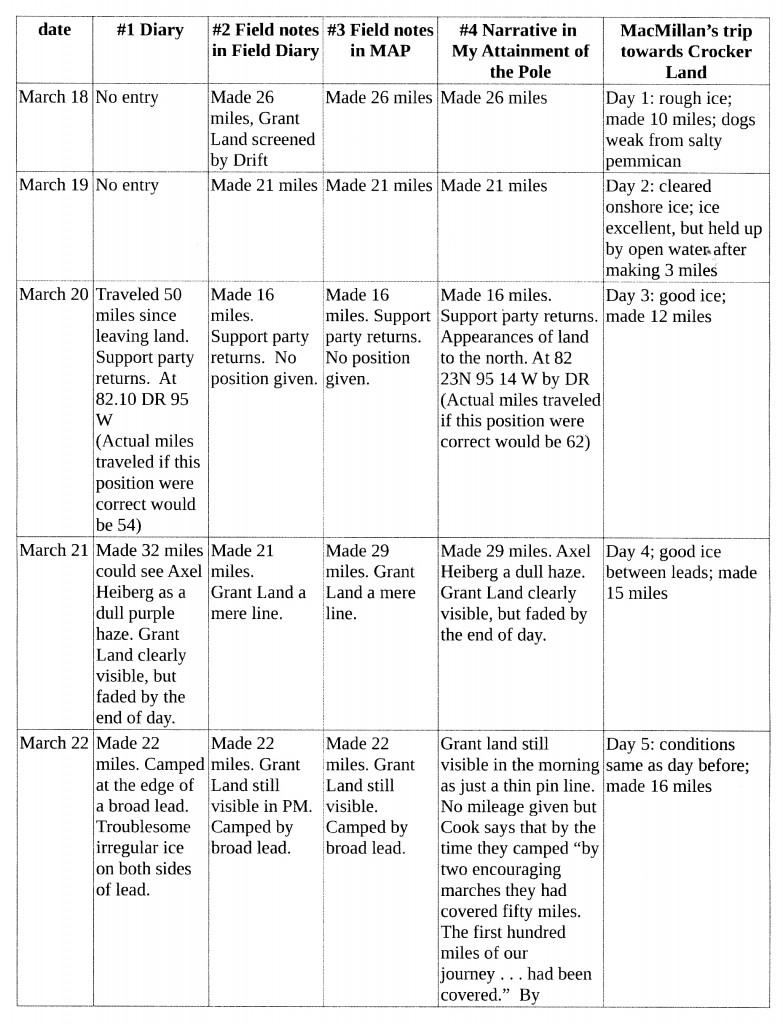

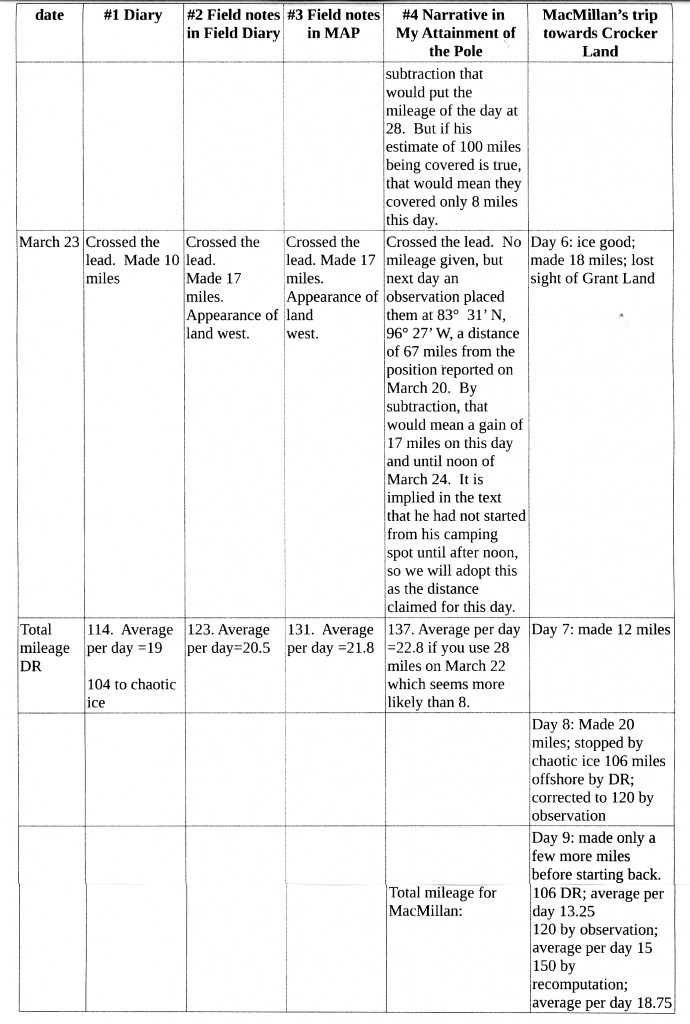

Let us now compare Cook’s various accounts of his journey on the sea ice in 1908 to Macmillan’s. There are four sources of data: #1: a Cook diary containing an incomplete circumstantial account; #2: Cook’s field diary that he kept on the first leg of his journey, which also contains a series of sequential notes covering his entire time on the ice; #3: his narrative account of his entire trip in My Attainment of the Pole and #4: his so-called “copy of the field notes” he kept on his journey, which were published as an appendix in that book. But first, a few words about the two manuscript sources.

#1 is an account covering the 6 days from March 18-23. The first entry is dated March 20, and summarizes that day and the two previous. This account is most similar in appearance and format to the separate diary Cook kept from the time he left Annoatok until he reached the point from which he headed out over the sea ice (#2). The size of its writing, the style of narrative, the data included and the incidental events described are all similar to the record he kept from leaving his winter base until he reached Cape Thomas Hubbard in that notebook. The “field notes” in that same book, on the other hand, contain entries for each day starting with March 19 and ending June 13, 1908, and continue that account, but the size of the writing and their format is entirely dissimilar. #1, starting on March 20, is consistent with the regular daily entries in his field diary kept on the first leg of his trip, but not with other diaries kept while Cook was not in the field. Nor is it consistent in content with either his “field notes” or the narrative account in his book. These “field notes” are in very small writing and are in the style of telegraphic phrases with little narrative content at all. And there is yet another contradictory source in the form of a “copy” of his published field notes, but, suspiciously, that also has entries for the days from February 19-March 18, not in either version of the so-called “field notes.” These additional entries do not match those in his original narrative notebook (#2).

After examining all of the diaries Cook wrote while on his expedition of 1908-09, the author concluded that the “field notes” in #2 were probably written, not during the time they describe, but during the period Cook overwintered at Cape Sparbo, or possibly even later—the period during which the Inuit remembered he “wrote and wrote.” For all of these reasons, the author is of the opinion that #1 is an actual field record of the first six days of his journey away from land, and that the other sources are after the fact or imaginary accounts. Here is a table comparing the content of the overlapping data these four sources contain, with an extra column with the relevant data from MacMillan’s original field diary:

A couple of things to notice in this comparison: The diary (#1) mileage total is the lowest. If this was an actual record and Cook was claiming the pole, in inventing a false narrative going all the way to the pole, he naturally would want to adjust his mileages upward for these days with each successive rewrite so he could reach the pole on April 21 with a reasonable daily average mileage. Notice that this is the exact pattern of the four successive accounts (if the author’s opinion of the sequence in which they were written is correct), the highest being his eventual published narrative. This is the pattern of fudging that is clearly demonstrated in his adjustment of dates in his field diary (#2) kept on the first leg of his trip. Also, notice the conflict on March 23 in his narrative account. The first five days in his “field notes” add up to 92 miles. On March 22 he says he went 22 miles. At the end of the sixth day in his narrative he gives no mileage for the day, but he says the first 100 miles have been covered, implying 8 miles for this day, but his statement that he had two marches in a row adding 50 miles to his total gives a figure of 28 miles for that day. And later in My Attainment of the Pole he says, “The goal lay 400 miles away,” which rules out the smaller figure.

A couple of things to notice in this comparison: The diary (#1) mileage total is the lowest. If this was an actual record and Cook was claiming the pole, in inventing a false narrative going all the way to the pole, he naturally would want to adjust his mileages upward for these days with each successive rewrite so he could reach the pole on April 21 with a reasonable daily average mileage. Notice that this is the exact pattern of the four successive accounts (if the author’s opinion of the sequence in which they were written is correct), the highest being his eventual published narrative. This is the pattern of fudging that is clearly demonstrated in his adjustment of dates in his field diary (#2) kept on the first leg of his trip. Also, notice the conflict on March 23 in his narrative account. The first five days in his “field notes” add up to 92 miles. On March 22 he says he went 22 miles. At the end of the sixth day in his narrative he gives no mileage for the day, but he says the first 100 miles have been covered, implying 8 miles for this day, but his statement that he had two marches in a row adding 50 miles to his total gives a figure of 28 miles for that day. And later in My Attainment of the Pole he says, “The goal lay 400 miles away,” which rules out the smaller figure.

All four accounts are consistent in saying that Grant Land (the name then in use for the uppermost portion of Ellesmere Island) was still visible until the end of the fourth day out. That would be at 82 miles in the diary (#1) account, or 92 in the other three. For the fifth day, #1-3 add a further 22 miles to this. But #4 because of the conflict noted above, is ambiguous. Only #2 and #3 are in agreement for March 23. These are the kinds of inconsistencies that are the mark of invention, not the recording of actual events as they happened. Therefore, in many respects there is reason to believe that #1 is probably a genuine account of Cook’s first six days on the ice (and even it has insertions and deletions within the original text. The reader can find a complete transcription of this diary account on pages 969 to 973 of the author’s book, Cook & Peary, the Polar Controversy, resolved, which shows these changes as well).

Since Cook was not traveling due north, but slightly west of north by his own account, he would have been traveling more miles to make the distance between the two latitude readings he gives. In his book Cook describes his method of deal reckoning: “We were traveling about two and one-half miles per hour. By making due allowances for detours and halts at pressure lines, the number of hours traveled gave us a fair estimate of the day’s distance. Against this the pedometer offered a check, and the compass gave the course. Thus, over blank charts, our course was marked.” Notice that he says his course is determined by compass alone, but he never mentions any corrections for magnetic variation. If you don’t know what that is, then any course set solely by compass can’t be accurate. This implies he is acting on his untenable idea of being on his “magnetic meridian,” which he believes lies approximately along the 97th parallel. As long as one has sight of a point whose bearings are known, such as Grant Land, one can steer an approximate course, but such a “system” of navigation is pure guesswork without such a bearing, and so anyone traveling out of sight of land would lose all points of reference for direction. This alone, for any sane traveler, suggests that Cook never really would have gone out of sight of land.

No matter what MacMillan said in his book, MacMillan found his own dead reckoning was always less than his celestial observations indicated. And the difference between the two was quite significant in their initial sight and even more so in Green’s later “recomputaion” of it. MacMillan and Green possibly had reason to want to inflate the distance they traveled, however. They wanted to make sure they traveled beyond the assumed location of Peary’s Crocker Land, but reading their diaries, one feels that they were very eager, because of the failing condition of their dogs, to turn back as soon as soon as possible. Not only were their dogs were dying in the traces, the season was advancing and the Inuit were urging them to “turn back as Dr. Cook had.” In this there is the suspicion that MacMillan and Green, like Cook, were adjusting their mileages upward as well, perhaps to assure others that their trip undoubtedly covered the distance necessary to assure that Peary’s Crocker Land had no existence at its estimated position. In his published narrative, MacMillan leaves open the possibility, for instance, that it might lie farther off shore than they expected. But, intentions aside, we have, like Cook’s various accounts, only their positional data to guide us.

If we just accept the difference between their first celestial observation and their DR figure of 106 miles, their DR was out by -12%. So if MacMillan said that they were still able to see Grant Land at a distance of 75-78 miles DR, adding 12% to that means it was visible at 84-86 miles. This matches up quite well with Cook’s statements of the distance he lost sight of it in #1’s diary entries, that seem to be an actual record written in the field. If you take Green’s recomputation to be valid, their DR was off by -30%. That means they would have to add 22 ½ miles, making the distance at which Grant Land was visible 97-99 miles. This raises the possibility that Cook could have been that far from shore without being inconsistent with the Inuit statement that they were never out of sight of land.

The various estimates of Cook’s distance from shore when he turned back given by MacMillan (see Part 6 of this series) range from 12-15 miles, and Henson estimated 20-25. The Inuit gave no estimate in Peary’s statement. However, in Borup’s notes, Etukishuk gave his own estimate that the distance he traveled with Cook was not as far as he had gone with Matt Ryan in 1906 (see Part 5). On Peary’s failed attempt to reach the North Pole that year, Ryan had headed one of Peary’s support divisions that he sent back in stages as the expedition drew away from land. Ryan stopped at the so-called “Big Lead,” where Peary was delayed by open water for one week. This was by observation located at 84° 38’, 115 miles north of Point Moss. This suggests Etukishuk thought that the distance he traveled with Cook and with Ryan were similar, but that he felt Cook’s was the lesser of the two, or he would not have made such a comparison, because even though Inuit had trouble gauging distances, 12-15 miles is hardly comparable to 115. Of the totals of the three accounts in the table, only the #1 diary account is less than Ryan went—one mile less, but none of the others are hugely incomparable.

MacMillan’s attempt to reach “Crocker Land” was the nearest contemporary journey to the northwest from Cape Thomas Hubbard after Cook’s. No one had every traveled before over the route MacMillan took, unless it was Cook. MacMillan’s experiences are not in dispute, though his various accounts of it, like Cook’s, are not consistent in every detail, either. Therefore, a comparison of MacMillan’s accounts of his trip with Cook’s accounts of his, should prove enlightening. If they have nothing in common, then that would be circumstantial evidence that Cook’s account is invention, with little basis in fact, and, as MacMillan said, he turned back only a very short distance from shore. Such a comparison is very apt, too, because besides the route, the two have so much else in common.

MacMillan was in the habit of rewriting his original diaries, “improving” his story with each new version, something he also had in common with Cook. So there are several “diaries. He also wrote several published accounts of his journey toward Crocker Land, and there is also the original diary of his companion Fitzhugh Green and a detailed account of the trip that Green published in several long magazine articles as well. The author has written a comparative study of all these materials, but it has not been published as yet due to copyright restrictions. That comparison runs about 70 pages, so it would be impossible to mention all the differences between these various accounts in this short space. So, to keep things simple, MacMillan’s journey is here recounted in the earliest of these sources. It is summarized comparatively with Cook’s in the last column of the table above.

Given the plethora of accounts left by each explorer, and their numerous variants, much more so for MacMillan’s than Cook’s, it’s probably best to compare apples with apples. Therefore in equating the two trips, we will assume Cook’s diary #1 is the closest to an original source that we have for Cook, and compare it to the known original source for MacMillan, his original diary now at the American Museum, where Green’s also is held. Since we are simplifying things, and we have only DR figures for Cook, we will use MacMillan’s DR figures as well.

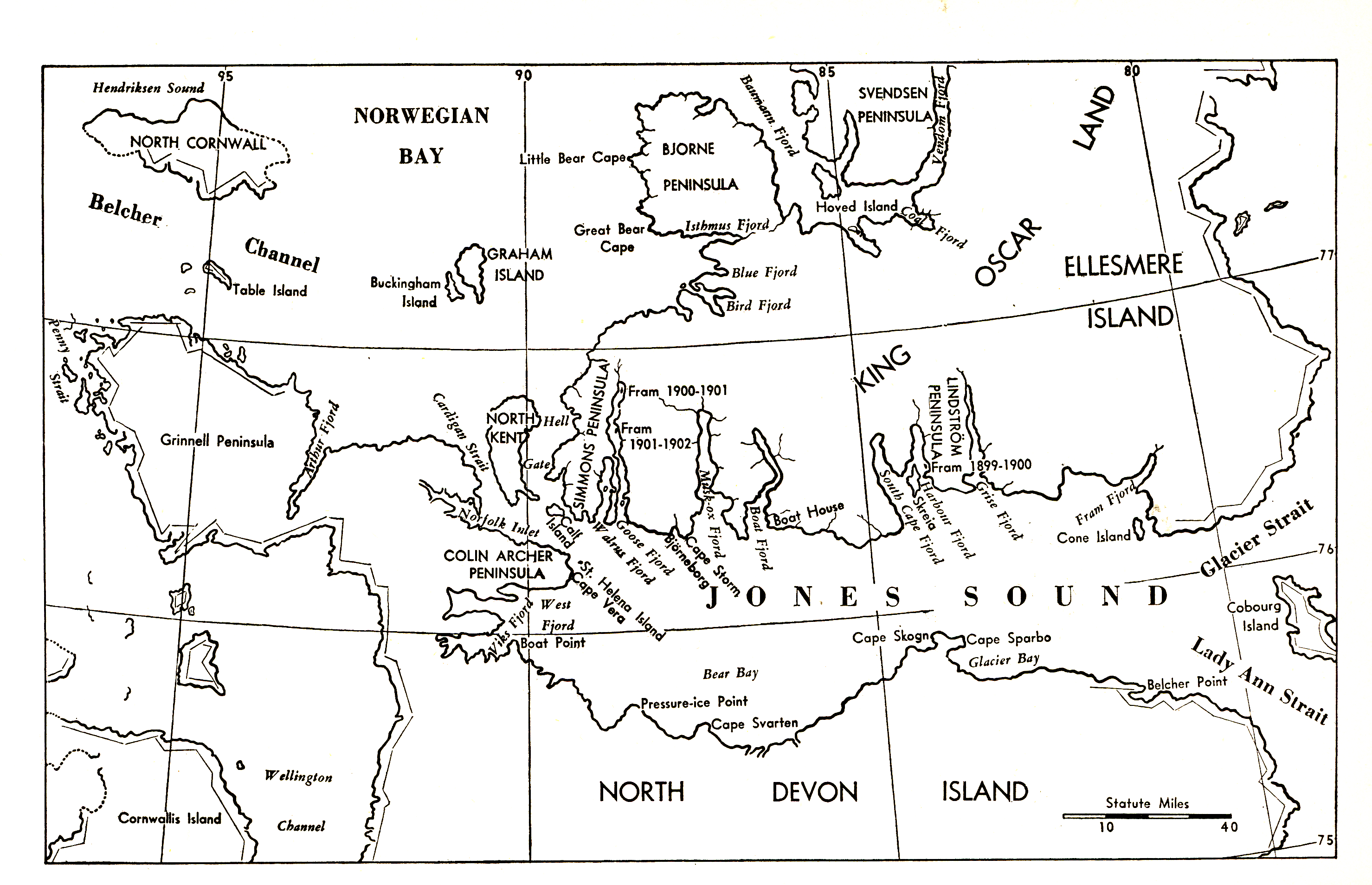

MacMillan’s forces were similar to Cook’s: himself, Fitzhugh Green, and the two Inuit, Pewahto and Etukishuk, the same Inuit who had been with Cook in 1908. They left Cape Thomas Hubbard on April 16th, 1914, three days later than Cook’s apparent start date of April 13th from exactly the same location. Both went northwest. Macmillan’s trip over it’s first six days went 74 miles by DR at a rate of nearly 12.33 miles per day, Cook’s went 114 at a pace of 19 miles per day.

The descriptions of the ice over which they traveled is very similar. In My Attainment of the Pole, Cook described the ice near shore as “slowly forced downward by strong currents from the north, and pounded and piled in jagged mountainous heaps for miles about the land.” MacMillan described it as “hard, rough ice all around us and as far as the eye can see.” Perhaps the fact that MacMillan was held up by open water the second day out, when he estimated he had traveled 13 miles from shore, was the basis of his later estimate that Cook turned back 12-15 miles from shore, because Peary’s statement said (erroneously) that Cook and his Inuit had turned back after two days of travel when they hit the first open water.

Once past this rough ice, Cook characterized the going as good: “For several hours we seemed to soar over the white spaces” before the ice changed to “thick fields of glacier-like ice giving way to floes of moderate size and thickness. These were separated by zones of troublesome crushed ice thrown into high-pressure lines, which offered serious barriers.” In his book, Macmillan said after the rough ice onshore, that four four days he traveled “over a rolling plain of old ice covered with low mounds and compacted drift.” But then the ice abruptly changed to “a perfect chaos of pressure ridge crossing and crisscrossing in all directions,” according to MacMillan. Cook also encountered this abrupt change: “We reached a line of high-pressure ridges. Beyond these the ice was cut into smaller floes and thrown together into ugly irregularities. . . hummocks and pressure lines which seemed impossible from a distance.” He took this to be “The Big Lead,” previously described by Peary in 1906.

On the eighth day out, MacMillan was turned back when he hit those chaotic ice conditions, which he placed at 106 miles out by DR. In Cook’s statement refuting Rasmussen’s second version of Cook’s journey told to him by the Inuit missionaries (see Part 9), Cook said he did not experience any open water until he reached “The Big Lead,” which he estimated was 100 miles out. In diary #1, Cook says he encountered chaotic ice conditions on his fifth day out at 104 miles DR. The original celestial observation at this point put MacMillan at 82° 11’ N, 108° 22’at which the compass variation was 178° out of true—nearly on Cook’s “magnetic meridian” of 180°. In this comparison (and remember, Cook claimed to be only person to have traveled over this route prior to 1914), the specific ice conditions each describes, although they can vary from year to year, are very similar. So, again, the two trips show extremely close correlation. But has any information come to light to show that the area over which MacMillan traveled has relatively consistent ice conditions, year to year, such as those we have seen exist between the Queen Elizabeth Islands?

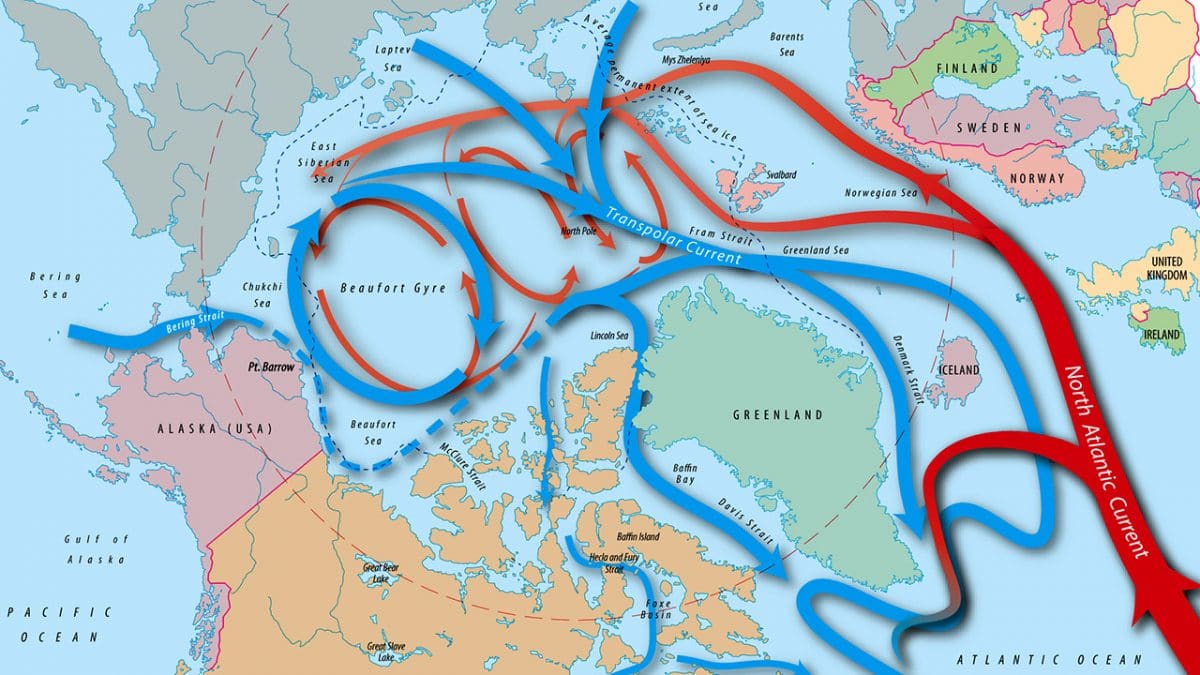

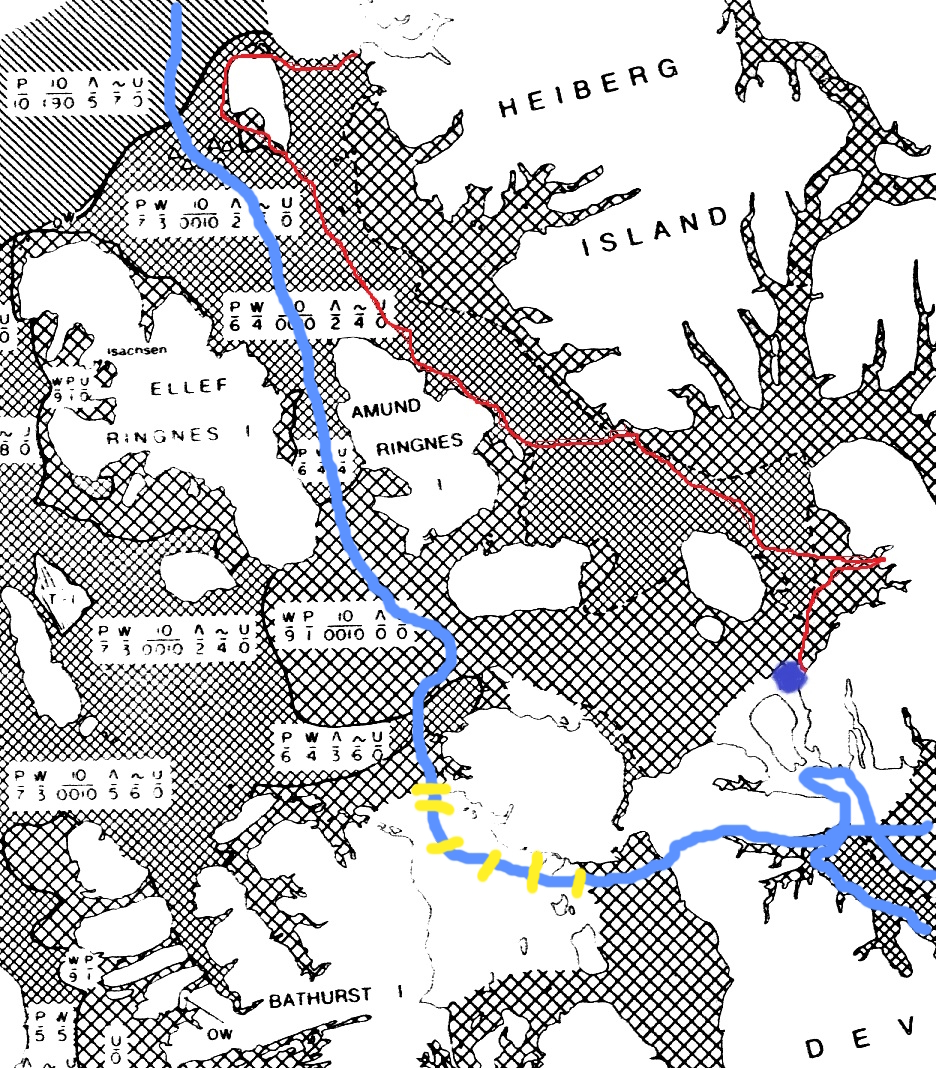

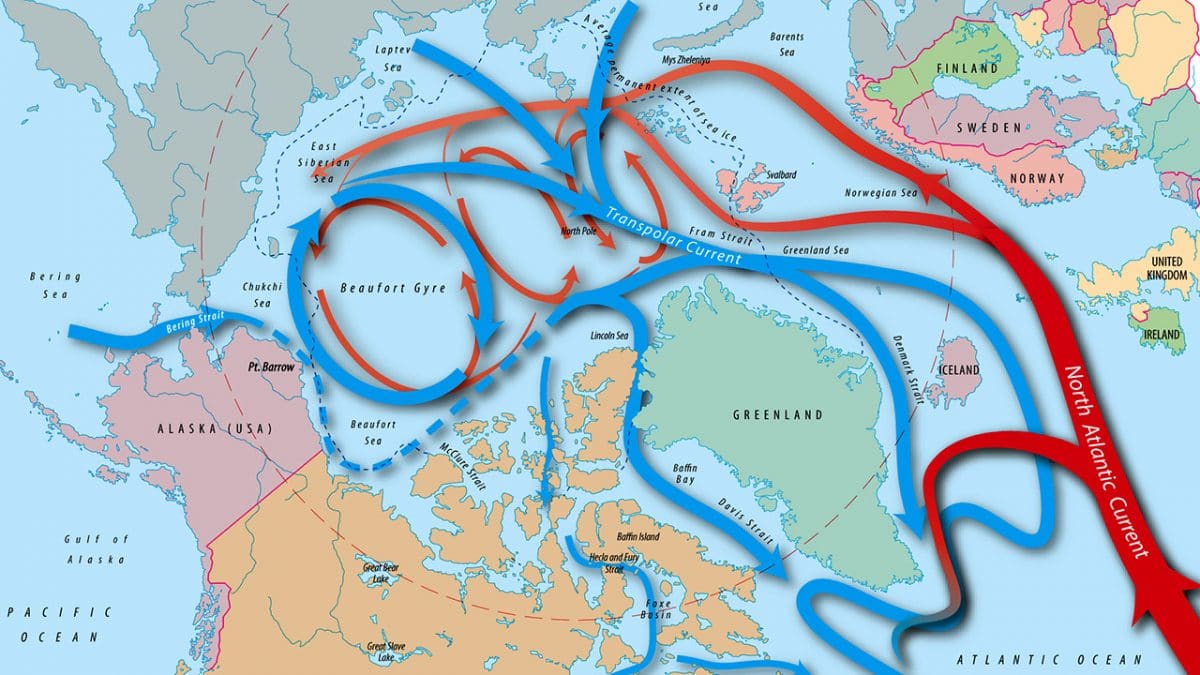

Beyond a comparison of the original written accounts, as we did in the case of the third leg of Cook’s journey (see Part 16), more circumstantial evidence can be gleaned from an examination of environmental conditions and factors in the area under consideration. Here is a chart showing the major currents in the Arctic Ocean:

Along the course MacMillan took, the ice is relatively undisturbed by tides and currents. In a paper delivered at Ohio State University in 1993, Captain Brian Shoemaker attempted to match Cook’s reports bearing on what is now know of these factors along his alleged route. The result was mixed, in that some factors north of 84°, especially drift data, didn’t match up with Cook’s reports, but Shoemaker contended conditions closer to shore did. For instance, he explained that over the route Cook claimed there was what he called a “current null area,” resulting in very little drift.

This is because of low tidal currents in the Queen Elizabeth Islands, due to their relative geographical locations to one another and the multi-year ice between them. Furthermore, the predominant current that flows from from the Behring Sea, west to east in the summer, is practically non-existent during the winter and early spring months due to the increased salinity of the water due to the freezing of freshwater rivers flowing into the sea from the northern coasts of Alaska and arctic Canada (the dashed line on the chart).

In Cook’s published narrative he noted an area beyond the initial rough onshore ice where there were a number of icebergs visible, some of which he judged to be grounded. From this observation he concluded that “the sea was very shallow for a long distance from land.” But in the same area, at 17 miles from shore DR, MacMillan made a sounding finding no bottom at 2000 fathoms, though he attributed some of this apparent depth to his axe, which he was using as a weight, being swept away laterally by a strong current. MacMillan was right. The sea is not that deep where he made his sounding, but it is not shallow a long way out, either, dropping off sharply to about 1500 feet along MacMillan’s route. But Cook’s observation may have been correct, nonetheless, though his conclusions were wrong. In Captain Shoemaker’s paper he noted that due to the lack of current, icebergs tended to congregate in the “current null area.”

In the early spring, during which both Cook and MacMillan traveled, Shoemaker wrote, the ice would not have been disturbed greatly until about 100 miles out on MacMillan’s known course. This disturbance is caused by the Beaufort Gyre, which flows strongly clockwise to the west at that point (see the chart). The Gyre apparently is caused by an upwelling of freshwater of unknown origin. As the climate has warmed in recent years, the strength of the Gyre seems to be weakening, boding possibly radical climate shifts for Europe, but its dynamics are still not well understood. MacMillan’s route would go right between the southwest shear zone caused by the strong clockwise circulation of the Beaufort Gyre and that of weaker counterclockwise easterly currents, spawned by remnants of the warm North Atlantic current, shown in red on the chart, leaving the area between the two with hardly any current at all. On the basis of this analysis, Captain Shoemaker said Cook’s narrative was consistent with then environmental conditions as far as 84° N, although these conditions were totally unknown in 1908, but were unconfirmed until MacMillan experienced their effects in 1914. It was MacMillan’s encounter with the southwest shear zone caused by the Beaufort Gyre, which MacMillan misattributed to the action of currents over shoal ground, that made further progress so difficult that he gave up his quest for Crocker Land and turned back to land. The fact that Cook first described this unknown western current and that MacMillan coming after him confirmed its existence, and also that each estimated it at precisely the same place, is evidence that both of them must have traveled about 100 miles to the northwest of the tip of Axel Heiberg Island, the place where it would be first observed along their respective routes.

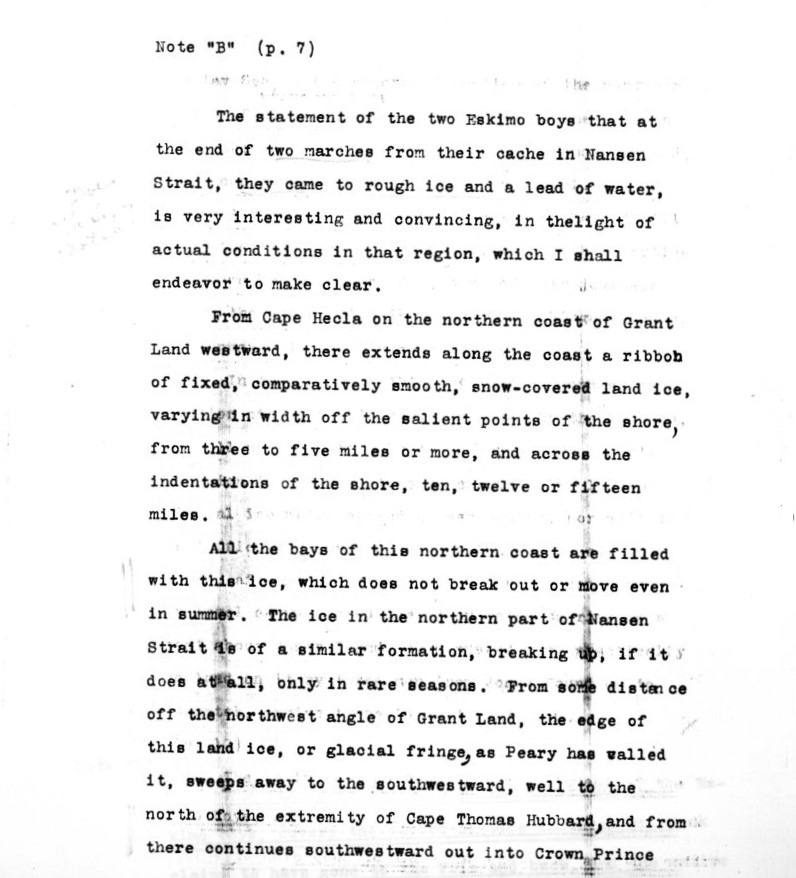

As noted, in Cook’s reply to Rasmussen’s contention (see Part 9) that he was stopped by open water near land, Cook said, “if so, the returning Eskimos would have reported it. The nearest water to land was at the big lead 100 miles off, where land was but a blue haze on the horizon.” Furthermore, this contention seems to be preserved in Inuit folk memory.

If we turn again to the account based on Inuit folk memory recounted by Inuutersuaq (see Part 12), it seems to be describing precisely such a journey as Cook and MacMillan each described. Points of congruence are given in bold print. It says “[Cook’s party] travelled a long time towards the north on the two dog sledges with the leader out in front on his skis as usual. The whole time they could make out faintly some of the coast of Grant Land [the north coast of Ellesmere Island] . . . Presently they came to large expanses of drift ice and after having travelled through this for some time ice packs came into sight. The leader stopped then and wanted to go no further. . . . They stopped for a long time in an area where there was enormous drift ice and pack ice which had broken loose from the polar ice. They reached the place in the middle of their most hopeless struggle and camped there. Their leader said nothing to them about having reached the North Pole. . . They said they were not so far from land. They of course meant that they could see some of Cape Columbia on the north coast of Ellesmere Land the whole time. It was moreover the place which [Peary] used as a depot and starting point for his [trip in] 1909, when he was on his way to the North Pole.” Only the details previously pointed out (that Cook didn’t use skis, and that Cook said nothing of reaching the pole) conflict with a description of either MacMillan’s or Cook’s narratives. Its description of conditions experienced while on the sea is very similar to what would have actually been experienced on a journey along their routes to about 100 miles offshore.

Counterbalancing this, however, is the statement of Inughito, who said that Cook’s marches were short while he was with him, and not as long as those he had made while working with Peary in 1909. Cook’s first three marches away from land, on which Inughito would have been with him, as can be seen from the chart, totaled 84 miles in #1, an average of 28 miles a day. Peary’s early marches to the Big Lead, where Inughito turned back on Peary’s 1909 attempt are not given daily distances in Peary’s account, but must have averaged far less than this—about 5 per day, because it took Goodsell 14 days to reach the point he turned back, which he estimated as about 80 miles north of his starting point. However, it is not at all clear that Inughito’s statement is referring only to the time he was out on the Arctic Ocean with Cook, or instead to Cook’s overall progress from his start from Annoatok. Cook took 48 days to reach Cape Thomas Hubbard, a distance by Cook’s own records of 735 miles including detours, for an average of 15.3 miles per day, though to be accurate, he did not travel at all because of delays on some of these days.

In 1909, Inughito was in Dr. Goodsell’s division and set out with him from Cape Columbia on March 1, 1909. They traveled north to the Big Lead. Here’s what Goodsell said in his March 14th 1909 entry, the day he turned back: “Left Commander Peary’s 7th igloo from Cape Columbia about 0 a.m. this morning. Dead reckoning 84° 20′, about 75-80 miles in direct line from Cape Columbia, 100 or more to the route we are compelled to follow.” On March 13, the Doctor had recorded that “Inughito frosted left heel, and it may be necessary for him to return to Columbia when I start to-morrow,” and indeed he took him with him. On March 19, the day he reached Cape Columbia, he mentions that he would be taking Inuguito and another Inuit, who had twisted a knee, back to the Roosevelt. He traveled back to the Cape in 5 days, arriving there early in the morning of the 19th. The latitude of Cape Columbia is 83° 11′. If Goodsell’s dead reckoning is accurate, he would be only about 69 miles due north of the cape. However, he estimates the ice conditions caused them to travel about 100 miles. So, in Borup’s record of what Inughito said, if the Inuit was referring to the total length of his marches with Peary compared to those when he was with Cook being not as long as Peary’s total, that is absolutely correct, because he was only with Cook three days.

If Cook and MacMillan actually reached the same place before turning back, as we have already noted, and if we compare MacMillan’s DR average to Cook’s, it will be seen that even the report that looks most likely to be a true account (#1) would work out to an average of 19 miles per day vs MacMillan’s of only a bit over 13. And indeed, Cook took only five days to reach the chaos of ice he describes in #1, while MacMillan took eight. However, Cook left land with the pick of the dogs from a large pack that had been fed on fresh meat during the whole outward journey to that point, whereas from the first day of his journey MacMillan continually complained in his diary that his dogs were in very poor condition because they had diarrhea from being fed on pemmican which contained an excessive amount of salt. Some of them actually dropped dead, and although the Inuit rode the sleds whenever possible, both MacMillan and Green walked the whole way to spare their teams the added weight, so much did they fear them giving out.

Anyone familiar with the early Antarctic journeys using dogs will be familiar with the vast difference in strength and stamina of dogs fed on fresh meat compared to dog pemmican—even saltless dog pemmican. Also, for the first three days of his journey away from land, Cook had four natives with him to help him get forward, whereas MacMillan and Green had just two. It is reasonable, therefore, to expect that Cook’s party would travel more miles per day against MacMillan’s poor performing teams, and would have reached the same place quicker than he.

Another possible source of evidence is the photographs taken during Cook’s alleged journey to the North Pole, vs MacMillan’s journey towards Crocker Land. Cook and Peary doubter, the astronomer Dennis Rawlins, finds it suspicious, especially considering Cook’s proven record of misrepresenting photographs, that few of Cook’s show him in the vicinity of any rough ice. Only one published picture, the one opposite Page 172 in My Attainment of the Pole, shows such ice.

There is another, unpublished one, in the Library of Congress, which was probably taken at the same place (see page 338 of the author’s book, The Lost Polar Notebook of Dr. Frederick A. Cook). However, the same might be said of the pictures MacMillan published. Only three of his show such ice in his book or in any of the articles he published before the book came out. Two of those (the one opposite page 76 and the lower of the two opposite page 78) are explicitly identified as having been taken at the location of the chaotic ice MacMillan encountered near his turnaround position; the other one is implicitly so. And beyond the ice pressed against Axel Heiberg Island, neither Cook nor MacMillan describe daunting ice impediments along their entire journey until they suddenly encountered chaotic ice, each about 100 miles from shore, the position known today as that where on such a course as MacMillan took they would have encountered the southwesterly shear zone caused by the Beaufort Gyre.

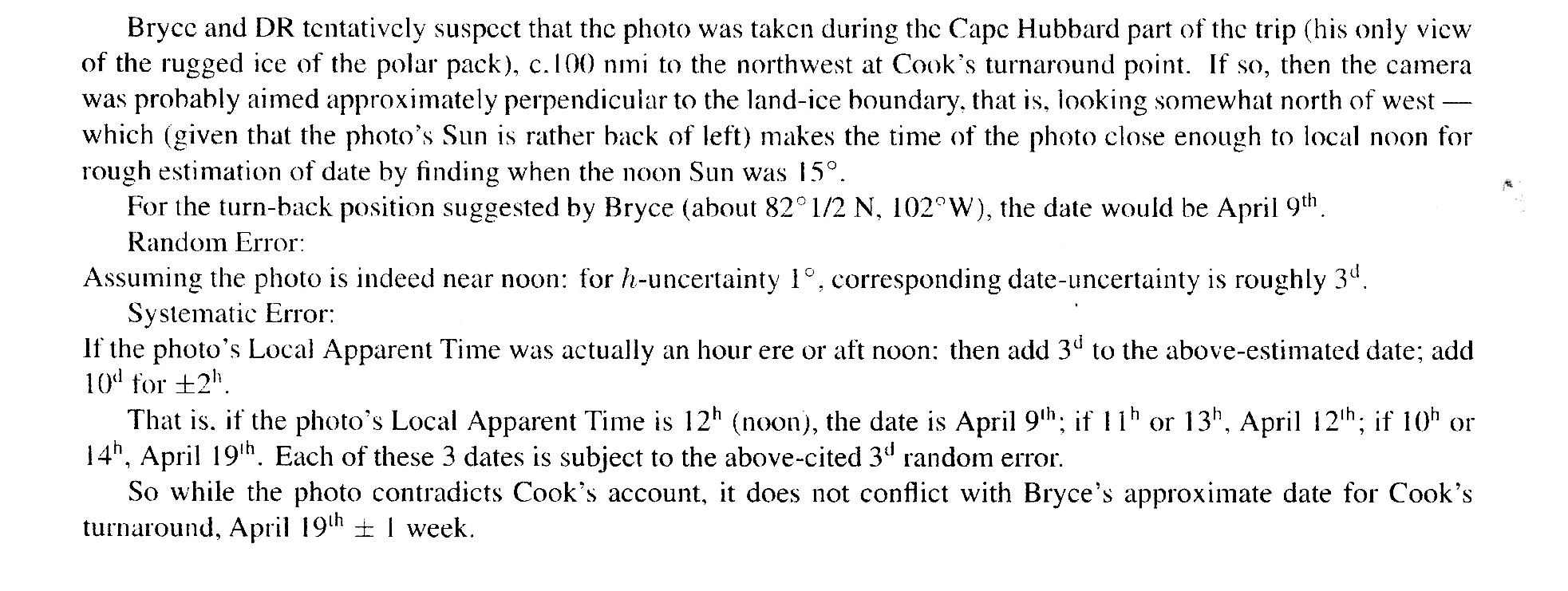

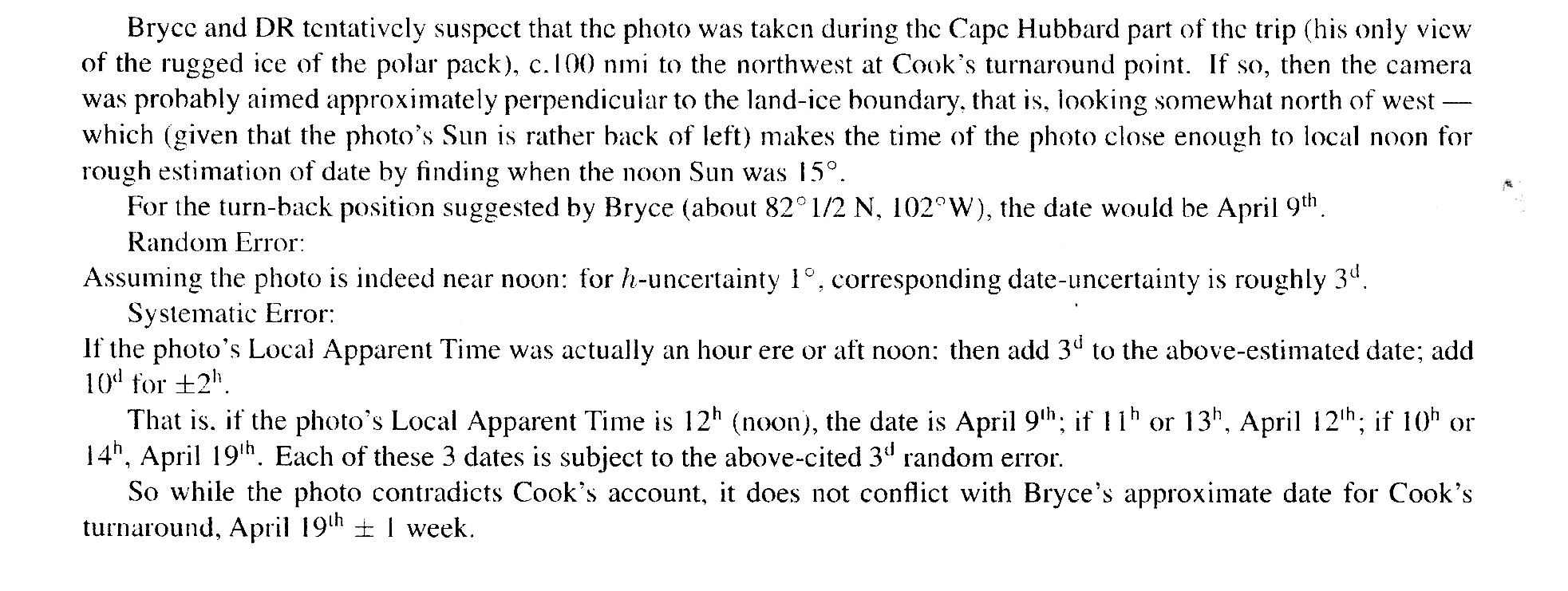

Initially, Rawlins considered as plausible my suggestion that Cook’s only published picture of rough ice might have been taken at his last camp before he turned back toward land. To test this possibility, he did a thorough photogrammetric analysis of it, using both the picture as published in his book and also a lantern slide of this image now in the Photographic Division of the Library of Congress, using shadows visible in the picture and other parameters derived from it. In December 2013 he sent me the results of his analysis. Here they are exactly as I received them:

This said, it must also be said clearly, that recently, Rawlins has disowned this analysis. He has instead accepted MacMillan’s story that Cook never went more than 12 miles (although MacMillan’s three different estimates ranged between 12 and 15 miles) as true. He has never furnished me with any other analysis or counter evidence for this other than Cook’s lack of photographs of rough ice, although I made him aware of some of the circumstantial evidence recounted in this series, and asked him to consider it in light of the many points of convergence with known physical conditions along Cook’s route, along with the many points of congruence with MacMillan’s similar journey in 1914, as described above. Rawlins has made it clear on numerous occasions that he despises Frederick Cook, and apparently on that basis alone is unwilling to give him credit for even a trip that fell more than 400 miles short of the North Pole.

We have already examined the physical conditions that existed between the Queen Elizabeth Island in Cook’s time, and by a comparison of the route outlined by the Inuit to Peary and that of Dr. Cook, have concluded that the Inuit version is supported by those conditions to a far greater degree than Cook’s. The limited documentary evidence available about that final leg of Cook’s journey also strongly favors their version as more trustworthy than Cook’s. In the case of his trip away from land, there is little documentary evidence, but what there is leans toward the author’s contention that #1 represents a circumstantial account of what actually happened, as does a comparison of it with MacMillan’s journey over the same area at the same time of year. So do all the then unknown physical conditions in the area the two expeditions traversed. Finally, Rawlins photographic analysis does not rule out the author’s approximate location for the position of Cook’s last camp, and there are no other Cook photographs that support him going any farther. In fact, his photographs of phenomena he experienced farther along his route, including those of “Bradley Land,” supposed to lie just north of Peary’s “Crocker Land,” and that of a “Glacial Island” within two degrees of the pole, have all been proven fakes.

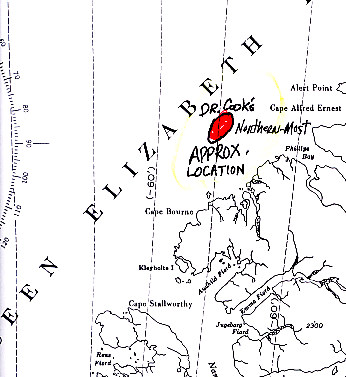

The author contends that the numerous points of congruence described above are too many to represent mere coincidences. So, on the basis of the evidence discussed here, he remains of the opinion that Frederick Cook made a journey of 6 to 8 days to the northwest of Cape Thomas Hubbard and was turned back at about the same latitude MacMillan was forced to do the same by the impossible ice conditions caused by the southwest shear zone related to the Beaufort Gyre, approximately 100 miles northwest of Cape Thomas Hubbard.

This does not mean that Cook was 100 miles nearer the pole when he turned back, because he was not going, and did not intend to go, due north. Assuming both encountered the southwest shear zone at about the same latitude, 82° 30’ N, from Cook’s mileage in #1 he would have been at about 102° W longitude. So his journey put him only about 65 nautical miles nearer the pole than the location of Cape Thomas Hubbard, or 462 miles short of it.

MacMillan’s DR calculations are nearly identical to Cook’s #1. Green’s “recomputation” put MacMillan at 82° 30’ N, 108° 22’ W. at which position MacMillan reported the magnetic declination, 178° W, not far from Cook’s “magnetic meridian.” We have no recomputation for Cook. But, of course, if Cook’s DR was in error to the same extent as MacMillan’s DR was, he would have ended up in almost exactly the same place Green’s figures showed. But working on just the best data we have, which in Cook’s case is sketchy at best, Cook’s DR position and Green’s result are about 48 miles apart, the distance between parallels of longitude at 82° 30’ N being only 8 miles apart. These positions have another implication for authenticity of Cook’s account: MacMillan’s course being farther to the west, it is reasonable to assume that MacMillan would have lost sight of land earlier than Cook, since Grant Land lay to the east.

This amazingly close positioning of the hypothesized turn about positions of Cook and MacMillan, again seems more than mere coincidence, just as does the congruence between Cook’s story of his journey in #1 and the Inuit folk memory of it. Even more interesting are the conclusions the Inuit drew about Cook’s intentions: “Ulloriaq theorized that [Cook] ‘was clear in his mind that he could not reach the North Pole. He therefore concentrated persistently on the trip to the large drift ice instead.’” As we shall see in the last installment of this series, that appears to be a fairly good description of what Cook actually did.

Sources not specifically mentioned in the text:

Bryce, Robert M., The Lost Polar Notebook of Dr. Frederick A. Cook, 2023.

Shoemaker, Brian, “Oceanographic Currents in the Arctic Ocean: Did Cook Discover an Unknown Drift,” Byrd Polar Research Center Report No. 18, 1998.

A couple of things to notice in this comparison: The diary (#1) mileage total is the lowest. If this was an actual record and Cook was claiming the pole, in inventing a false narrative going all the way to the pole, he naturally would want to adjust his mileages upward for these days with each successive rewrite so he could reach the pole on April 21 with a reasonable daily average mileage. Notice that this is the exact pattern of the four successive accounts (if the author’s opinion of the sequence in which they were written is correct), the highest being his eventual published narrative. This is the pattern of fudging that is clearly demonstrated in his adjustment of dates in his field diary (#2) kept on the first leg of his trip. Also, notice the conflict on March 23 in his narrative account. The first five days in his “field notes” add up to 92 miles. On March 22 he says he went 22 miles. At the end of the sixth day in his narrative he gives no mileage for the day, but he says the first 100 miles have been covered, implying 8 miles for this day, but his statement that he had two marches in a row adding 50 miles to his total gives a figure of 28 miles for that day. And later in My Attainment of the Pole he says, “The goal lay 400 miles away,” which rules out the smaller figure.

A couple of things to notice in this comparison: The diary (#1) mileage total is the lowest. If this was an actual record and Cook was claiming the pole, in inventing a false narrative going all the way to the pole, he naturally would want to adjust his mileages upward for these days with each successive rewrite so he could reach the pole on April 21 with a reasonable daily average mileage. Notice that this is the exact pattern of the four successive accounts (if the author’s opinion of the sequence in which they were written is correct), the highest being his eventual published narrative. This is the pattern of fudging that is clearly demonstrated in his adjustment of dates in his field diary (#2) kept on the first leg of his trip. Also, notice the conflict on March 23 in his narrative account. The first five days in his “field notes” add up to 92 miles. On March 22 he says he went 22 miles. At the end of the sixth day in his narrative he gives no mileage for the day, but he says the first 100 miles have been covered, implying 8 miles for this day, but his statement that he had two marches in a row adding 50 miles to his total gives a figure of 28 miles for that day. And later in My Attainment of the Pole he says, “The goal lay 400 miles away,” which rules out the smaller figure.