Cook & Peary, twenty-five years on

Written on February 17, 2022

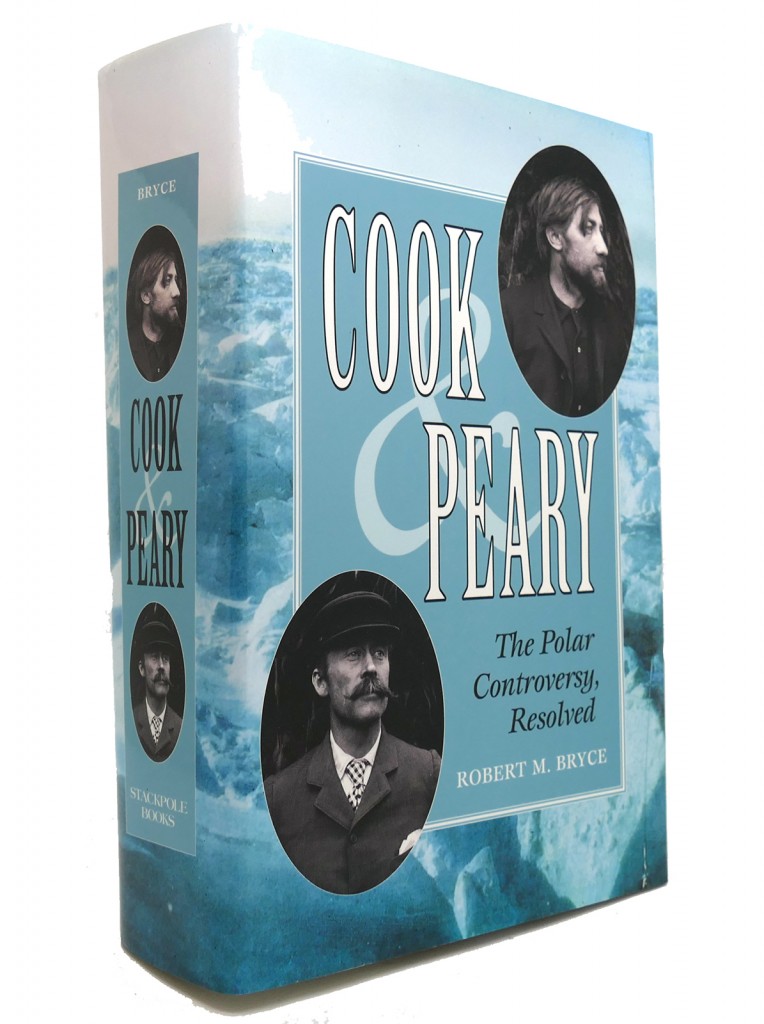

Twenty-five years ago today, February 17, 1997, Cook & Peary, the Polar Controversy, resolved, was published.

I’d first taken an interest in the titanic dispute over who first reached the North Pole in the mid-1970’s and read the narratives Cook and Peary had written about their attainments of the North Pole. I also made an effort to read all the books that had been written about the dispute going back to Captain Thomas F. Hall’s pioneering analysis of 1917, Has the North Pole been Discovered? I had also read many magazine articles published during the controversy, so that I had a good grounding in the primary published sources on the subject. There things rested until the controversy was rekindled by a discovery in Peary’s papers at the National Archives in 1989 that seemed to indicate he had fallen far short of the Pole in 1909. With Peary’s claim in doubt, the claim of his rival, Dr. Frederick A. Cook to have beaten him to the Pole, though long discredited, received new attention.

I made contact with the Frederick A. Cook Society to see if access could be had to comparable papers of his discredited rival. I was told Janet Vetter, Cook’s only direct descendant, owned Dr. Cook’s papers, and after writing to her, I received a letter hinting that she might grant such access. But before I could arrange anything more concrete, Ms. Vetter died suddenly on August 10, 1989, at the age of 51. Under the terms of her will, her grandfather’s papers were to go to the Library of Congress, just 40 miles from my home.

When I read of the gift, I wasted no time in contacting the Library of Congress and was told that Vetter’s papers would be arriving sometime in early 1990. A further inquiry revealed, however, that there were no plans to catalog the papers in the near future, but that some of the most important ones, including Cook’s original field diaries had already arrived and could be seen by appointment. After I examined these, I urged the head of the manuscript division, Dr. James H. Hutson, to expedite processing of Cook’s papers, and by that Summer I was at work reading the entire gift.

Not far into this examination, I began a parallel examination of the vast Peary gift, housed just seven blocks away from the Library of Congress at the National Archives. For a person as steeped in the published Cook-Peary literature as I was, I quickly realized that despite all the previous articles and books already written on the Polar Controversy, there was much significant that had never been known about the dispute between the two explorers. I was certain that I could make an original contribution to the subject through a systematic and careful examination of these original materials. I decided then and there to write a book evaluating their content and how they related to the historical controversy and the larger question of it as an example of historical truth.

The result was published seven years later as Cook & Peary, the Polar Controversy, resolved. It was the fruit of three years of intensive research into not only the papers housed in Washington, to which I commuted three times a week for nearly six months, but also into just about every accessible collection of primary documentation on the subject, including a detailed reading of much of the massive printed literature, primary and secondary, personal interviews with living connections to the story, hundreds of letters of inquiry, tens of thousands of miles of travel and eventually eight years of writing and revision. All this primary material was documented by more than 2,400 source notes at the book’s end. By 1993 the manuscript, which filled an entire box of continuous-feed computer paper, was in reasonably good shape, and I set off on another three-year quest to find a publisher for it.

Many publishers were enthusiastic after they read my cover letter; they were less interested when they weighed my manuscript. Eventually, I sent only the first three chapters to Stackpole Books after getting a positive response to my proposal, avoiding mentioning the bulk of the whole manuscript. There I found an editor on the same page as I, Sally Atwater; she asked for three more chapters, and by the time she had read them, she was hooked. A contract was signed. But even as I prepared my manuscript for actual publication, new things came to light, new leads developed and new revisions were made as a result, some even after the galley proofs were printed.

The book got a lot of attention upon its release, with feature articles in the Washington Post ’s “Style” section and the US news section of the New York Times. These led immediately to a number of interviews, including segments the night of publication aired on ABC World News Tonight and MSNBC, and later, appearances on NPR’s The Diane Rehm Show and The World, as well as in two documentaries produced by the BBC.

Apparently, however, few absorbed the import of the new evidence I had uncovered, let alone that of the whole sweep of my 1,000+ page book, even those with prior knowledge of the subject or those who had the patience just to study my book thoroughly. It was dismissed out of hand, of course, by Cook’s partisans. They had convinced themselves that I was writing a book that would vindicate Cook and were shocked that it produced convincing evidence that he had lied about the results of his attempt to climb Mt. McKinley, and his real, but equally failed, attempt to reach the North Pole. But even some others scoffed at the subtitle, “The Polar Controversy, resolved.”

They may not have been Cook partisans, but they had some stake in wanting to see the controversy continue, like proprietors of “adventure” companies that promoted ultra-expensive “Last Degree” treks to the North Pole, and persons with some previous self-interest in justifying their version of the controversy that they had put into print, or others who simply liked to argue over it interminably. They said there would never be an end to the controversy, simply because there would never be possible to produce actual documentary evidence that proved Cook’s story a lie—the proverbial “Smoking Gun” that would end it, absolutely.

In the wake of my publication of Cook’s fake “summit” photo in DIO, following my recovery of it from a badly faded copy and its subsequent publication in the New York Times in 1998, Cook’s McKinley claim, that also still had its advocates even beyond The Frederick A. Cook Society, and which was called in mountaineering circles, “The Lie that Won’t Die,” finally breathed its last.

After my book was reviewed widely, reference after reference published subsequently cited Cook & Peary in their evaluation of the rival explorers’ claims. By the time of the centennial of the outbreak of the dispute between the two explorers in 2009, it had become a virtual consensus that certainly neither Cook nor Peary reached the Pole when he said he did, or ever. Even the National Geographic Society had nothing officially to say in support of Peary on the 100th Anniversary of his supposed attainment or to commemorate it, something they had never failed to do on any significant occasion in the past involving Peary’s alleged discovery.

Even the publication of what was, in effect, a feeble rewrite of Andrew Freeman’s The Case for Doctor Cook, that appeared in 2005 under the title True North, did nothing to stem the tide of dismissing Cook’s polar claim out of hand, as it had been early on, reversing the trend of a more positive consideration of Cook’s polar attempt in the light of the collapse of Peary’s claim.

However, my subsequent publication of The Lost Notebook of Dr. Frederick A. Cook in 2013, which closely analyzed a notebook whose existence had been unknown to scholars before the publication of Cook & Peary, finally provided the “Smoking Gun” that skeptics doubted would ever be produced, proving Cook could not possibly have reached the North Pole in 1908. Between the two books, the greatest geographic controversy in history, The Polar Controversy, had finally and truly been resolved.

Filed in: Uncategorized.