The Cook-Peary Files: The Barrill Affidavit, Part 4: Who got what?

Written on September 10, 2022

This is the 21st in a series examining significant unpublished documents related to the Polar Controversy.

As we have already seen, the newspapers carried an account saying Ed Barrill had been bribed with $5,000 to make his affidavit against Cook, but that General Hubbard was quoted several times as denying he had received anything for his signature. James Ashton’s only known public comment appeared in the New York Times on October 30, 1909. There he was quoted as saying that Barrill had received $100-$200 for expenses, but that he would have to look it up in his expense books to be sure.

In his chapter “The Mt. McKinley Bribery” in My Attainment of the Pole, Cook contended that Barrill visited Seattle, and in the presence of Seattle Times editor, Joe Blethen, dickered for sums ranging up to $10,000 for an affidavit that would discredit him. Eventually, Cook said, Barrill failed in this attempt, and decamped to Tacoma to meet with James Ashton. Soon after, Cook alleged, he was seen at a Tacoma bank by a witness who claimed he had been passed $1,500 in large bills. For this and “other considerations,” Cook claimed, Barrill had signed the affidavit published in the Globe.

These statements were based on solid evidence. It came in the form of a long letter from one C. O. Anderson, an attorney in Kennewick, WA, who claimed to have interviewed the witness to the Barrill payoff:

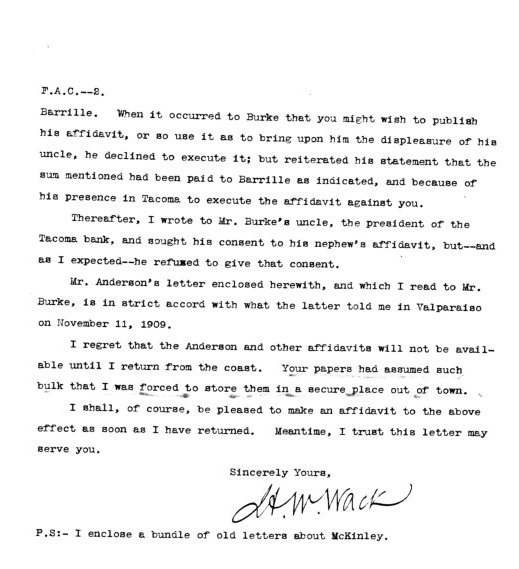

H. Wellington Wack, Cook’s lawyer, followed up by visiting this witness in Indiana. He forwarded a summary of what he had found to assist Cook as he was finishing up the text of his book in early 1911:

The affidavits Wack mentions here have as yet not come to light.

Early in October 1909, rumors of plans to bribe Barrill had already induced Cook to take countermeasures. He wrote Barrill enclosing $200 and asking him to meet him in St. Louis on October 6, cautioning him to “Kindly give no press interviews whatsoever.” He also sent Printz $500, paying him his full back wages.

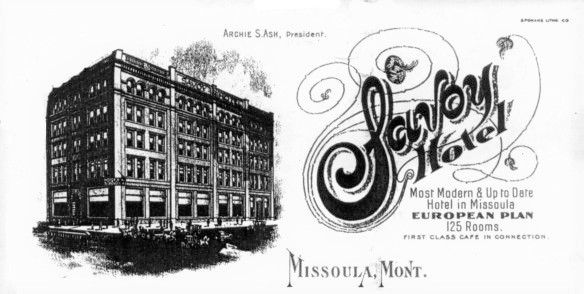

When Cook’s serial story of his conquest of the North Pole had begun to appear in the New York Herald, Roscoe C. Mitchell, one of the paper’s reporters, had been assigned to accompany Cook as his “confidential agent” to watch over the Herald’s interests. Cook now dispatched him, under the direction of his attorney to Missoula, Montana.

At the new Savoy Hotel there, two local lawyers, Col. Tom Marshall of Missoula, and “General” Elbert D. Weed, of Helena, assisted Mittchell in finding witnesses to counter any potential statements made by Barrill. The lawyers took affidavits from Barrill’s real estate business partner, C. G. Bridgeford and several others. Fred Printz, who reportedly was doing some dickering himself for as much as $1,000, also was interviewed by Cook’s lawyers at the Savoy. Mitchell was later joined there by Cook and his private secretary, Walter Lonsdale.

Statements by Bridgeford had been published in the New York Herald on October 12. He claimed that Barrill had shown him his Alaskan diary a number of times, and that the story it contained corroborated Cook’s account. When Barrill’s diary was published in the Globe, this proved to be the case, as was Bridgeford’s physical description of the diary, which was completely accurate, giving evidence that he had indeed seen it. He also testified that Barrill had held forth on the climb a number of times and that his story had been consistently the same: that he and Cook had reached the summit of Mt. McKinley. Others in the community verified this was true as well.

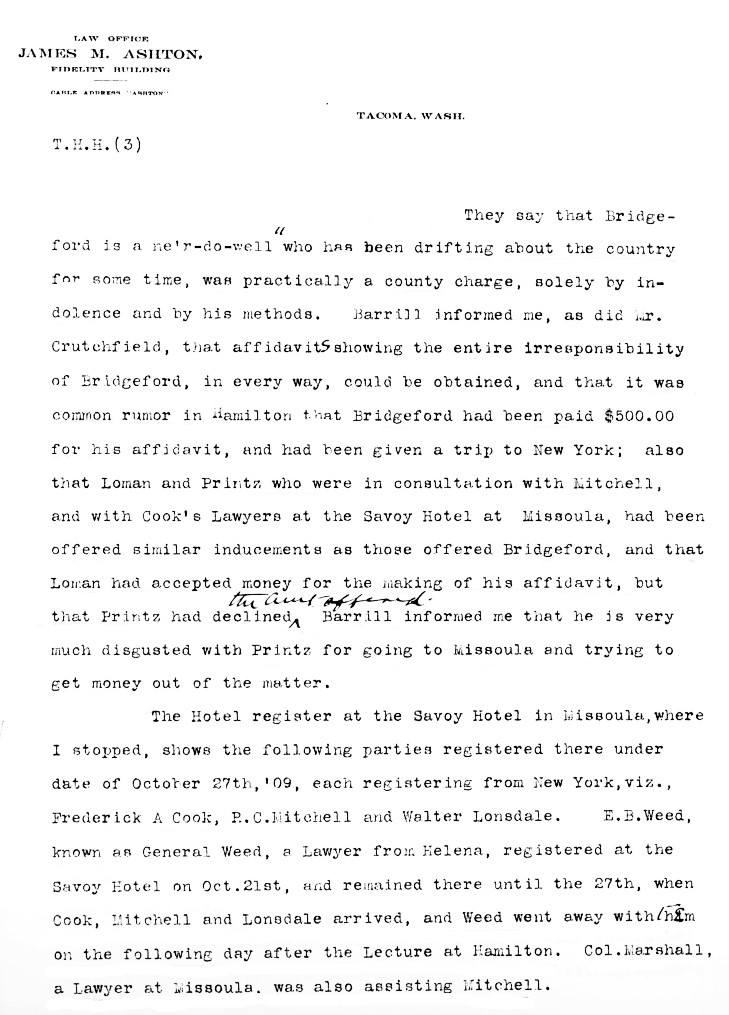

These moves did not go unnoticed by Ashton, who had his own agents working the ground in Montana. He wrote to General Hubbard about what he found out and also sought to discredit Bridgeford.

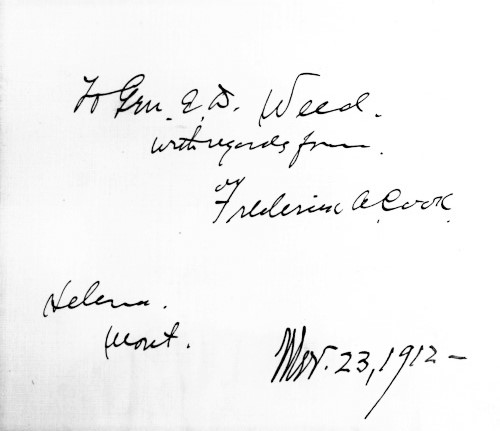

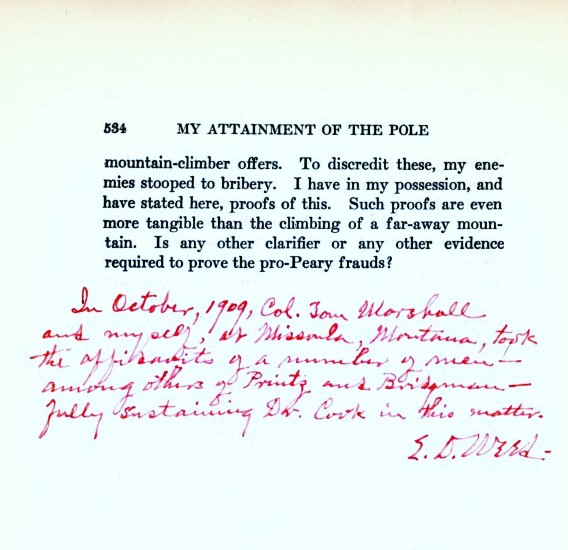

In the copy of My Attainment of the Pole that Cook gave to Weed in 1912, the lawyer made a number of annotations in red ink throughout. On page 534 he confirmed Ashton’s statements, but made the Freudian slip of writing “Bridgman” for “Bridgeford” as one of the men from whom Cook’s contingent obtained affidavits.

“In October 1909, Col. Tom Marshall and myself, at Missoula, Montana, took the affidavits of a number of men – among others of Printz and Bridgman – fully sustaining Dr. Cook in the matter.

(signed) E. D. Weed”

Some have assumed, based on press reports and the discovery of the $5,000 Hubbard bank draft drawn by Ashton among Peary’s papers, that Barrill received the full $5,000 (about $150,000 today), but it should be remembered that Ashton had told Hubbard the amount was to cover “everything.” Everything would include paying off not only Barrill, but also the other four persons whose affidavits the Globe eventually published. It also would include the expenses of various parties, including Walter Miller, who sought out and brought the various wintnesses to Ashton, or arranged the taking of their affidavits. Then there was the cost of having Barrill’s lengthy diary accurately deciphered and transcribed, paying for Barrill and his wife’s trip to New York City, and other expenses such as transportation, lodging and meals for the various sworn witnesses, etc. And this is assuming that none of Ashton’s fees were included in the sum, which well they might have been.

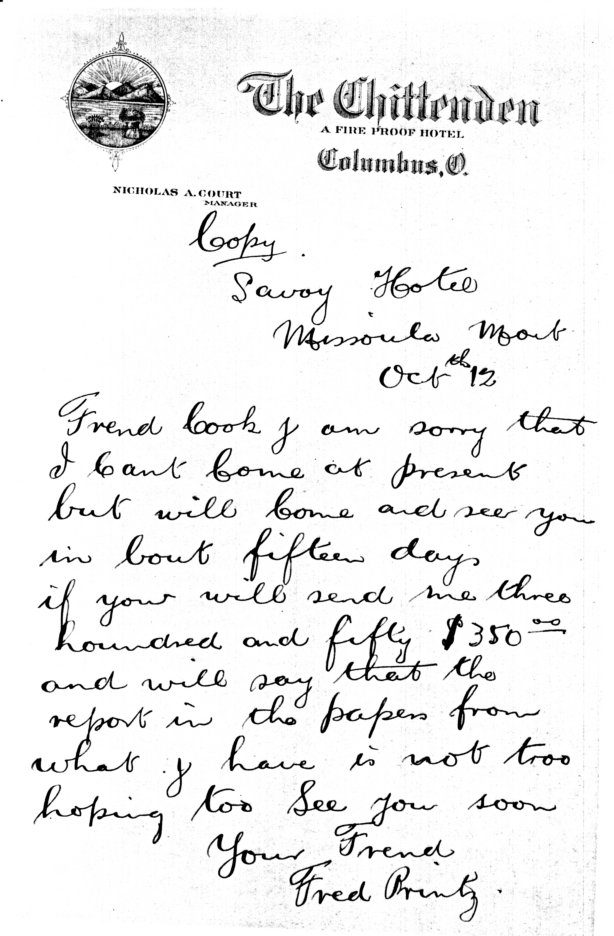

It’s probably accurate then, based on the witness, that Barrill actually received only $1,500, but still a substantial sum. Cook claimed that Printz eventually got $500, after being promised more, and that both Miller and Beecher “were promised large amounts, but were cheated at the ‘showdown.’” Just exactly what the others got is unknown. Cook also claimed Printz tried to sell Roscoe Mitchell an affidavit supporting him for $1,000, was turned down, and later solicited $350 in a letter dated October 12. The letter, which is quoted in Cook’s book on page 525, was among the holdings of the Frederick Cook Society before they were transferred to Ohio State, and presumably is there now.

However, it’s curious that it says it is a “copy” and is on the stationary of the Chittendon Hotel in Columbus, OH, when it is said to have been written at the Savoy in Missoula. For Printz’s part, he denied ever having written such a letter. Because he ended up signing an affidavit for Ashton, we can assume he got nothing from Cook’s side.

The Anderson and Wack letters were in the collection of the Frederick A. Cook Society, presumably now at Ohio State. The undated letter from Cook to Barrill enclosing $200 and the Ashton letter are at NARA II. Weed’s copy of My Attainment of the Pole is the possession of the author.

Filed in: Uncategorized.