Looking back on the eve of the centennial of the great Polar Controversy.

Written on September 1, 2009

It all began with these words sent in a telegram from Lerwick, Shetland Islands, on the morning of September 1, 1909:

REACHED NORTH POLE APRIL 21, 1908. DISCOVERED LAND FAR NORTH. RETURN TO COPENHAGEN BY STEAMER HANS EGEDE. FREDERICK COOK.

It will be 100 years ago tomorrow that those fateful words broke upon an unsuspecting world. For the next four months the world, and especially the United States, was obsessed with the controversy that they began over the question of who was the discoverer of the North Pole, Frederick A. Cook, who sent the telegram, or Robert E. Peary, who cabled five days later: STARS AND STRIPES NAILED TO POLE, and who three days after that accused Cook in making his prior claim, of simply handing the world a “Gold Brick.” But will the world now take any note of the centennial of the greatest scientific dispute of all time? To judge by the attention garnered by the hundredth anniversaries of the two explorer’s actual claims, probably it won’t. Apparently this shows the current state of the debate: both claims are now generally discredited, absolutely so for those who have studied the complicated details; the mystery is gone, and with it the fascination. Little is left to argue over except by the partisans. Those partisans on both sides still exist, mind you, and as long as they do, they still want everyone to believe their man is the true discoverer.

Cook’s centennial passes virtually unnoticed.

The only event marking Cook’s 1908 claim was a gathering of the dwindling faithful of the Frederick A. Cook Society in rented rooms in New York City. That’s not really surprising, since Cook’s claim was discredited just two months after he made it, when the Konsistorium of the University of Copenhagen, the experts that Cook chose to review his “proofs,” rendered it’s judgment: “The Commission is therefore of the opinion that there can not in the material which has been submitted to us for examination, be found any proof whatsoever of Dr Cook having reached the Northpole.” Yet the faithful duly met on May 6, 2008, but the only note made of it by the outside world was a short piece that appeared on March 30 in the local Brooklyn section of the New York Times by freelance writer James Vescovi. At that meeting members of the Cook Society and several academics and “polar historians” they regularly feature at these paid-for gatherings, presented papers reciting their mantras on how Cook was cheated of his claim and his fame by a great conspiracy, or on academic topics unrelated to him at all.

Cook vs. Dyche? Cook’s supporters are as confused as usual.

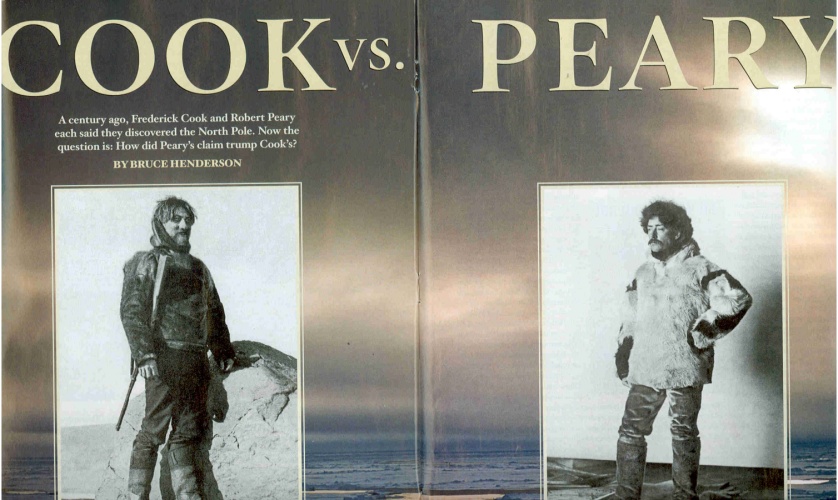

Yet Peary’s 1909 claim got nearly as little attention. If Tom Avery hadn’t been using the date to launch his book, To the End of the Earth, detailing his 2005 attempt to bolster Peary’s claim by duplicating Peary’s timetable of 37 days in getting to the Pole, April 6, 2009 might have passed with little notice either. The only print article specifically marking the centennial was a piece entitled “Cook vs. Peary,” in the Smithsonian magazine’s April number, whose purpose, ironically, was to raise the possibility that Frederick Cook might be the true discoverer. The author, Bruce Henderson, who has had associations with the Cook Society, tried to rehabilitate Cook with True North, an essentially plagiaristic rewrite of the first Cook-slanted biography, The Case for Dr. Cook, published in 1961 by Andrew Freeman.

In a preface to the Smithsonian article Henderson predicted that “there’s going to be a lot of stories about the centennial of the discovery of the North Pole by Robert Peary.” He was wrong on that, as he was about so much else in his book. Not even the National Geographic Society made any note of the 100th anniversary of Peary’s claim to be the discoverer of the North Pole, a title it had helped to create and in the past had often vigorously defended. In so doing, Smithsonian’s article stood out as unusually singular, and left it with the egg on it’s face that has usually been reserved in the past for the National Geographic Society, whenever the Polar Controversy raised it’s head. The editors at Smithsonian (the magazine relies entirely on free lance writers, not Smithsonian employees, and disclaims that the views it contains are necessarily those of the Smithsonian Institution) were apparently the only ones so ill informed as to allow themselves to appear to endorse Cook’s claim, which is now almost universally recognized as an attempt at the greatest circumstantial scientific fraud of the 20th Century. Actually, the article should have been entitled “Cook vs. Dyche,” as among its numerous gaffs and biased versions of events, the other explorer facing down Cook on the double-page spread that introduced the article is not Peary at all, but L. L. Dyche, a professor at Kansas State University, who went twice to Greenland, once with each of the contentious explorers, to gather biological specimens.

Dr. Cook at Bowdoin.

The only major commemoration of Peary’s centennial took place at Peary’s Alma Mater, Bowdoin College, in Brunswick, Maine. (see Blogroll) It consisted of an internal symposium and a very well mounted exhibition that brought together many key artifacts of Peary’s 1908-1909 expedition in the rooms of the Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum under the title “Northward over the Great Ice.” Among them were one of Peary’s sledges and the silk flag Peary carried on all of his journeys after 1897, and from which he cut portions to leave at key points in his travels, including a long diagonal swath he claimed to have buried at the North Pole in 1909. The exhibit also had a number of interesting items related to the other members of Peary’s team, including a newsreel interview with Matthew Henson, Peary’s long-time servant turned assistant.

Cook received more attention than expected at Bowdoin, including equal-sized photographic portraits in one frame with a summary of the controversy mounted beneath, captioned “Heroes or Villains?” An enlargement of Cook’s photo of an igloo that he said he erected at the North Pole was also on display in the hall.

The Case For Dr. Cook.

Within the exhibition itself, Cook got a case all to himself containing a map of his reported route, a picture of the remains of the stone igloo at Cape Hardy (notice: it is not a cave) where he spent the winter of 1908-1909 with his two Inuit companions, and several souvenirs of the dispute, including the cover page from a French publication showing Cook and Peary in a fist fight at the North Pole while penguins look on. Of course, there have never been any penguins at the North Pole, but then again Cook and Peary were never there either.

Is the Polar Controversy nearing an end?

Considering the level of the centenary commemorations of the respective explorer’s claims, with their centenaries past, it appears now that the Polar Controversy is finally coming to a close. Naturally enough, the world doesn’t often note anniversaries beyond the 100th , after all. And the Polar Controversy from the start has always been sustained by two things: power and money. The National Geographic Society has, at least publicly, lost interest, and without it’s power of publicity, the doubts about Peary are becoming permanent. The war chest provided to the Frederick A. Cook Society by the will of Dr. Cook’s last lineal descendant to keep up the fight, is now, by the admission of the society’s president, Warren B. Cook, at low ebb. That money has been the largest factor in promoting Cook’s fake over the last 20 years. When that money runs dry, Cook’s claim will probably sink quietly into the oblivion it deserves. But his fascination as an unusually forward-looking personality and romantic fabulist will probably persist. On the other hand, Peary’s self-centered, imperialist personality and once-common, disdainful attitudes toward “inferior races” has little appeal today, and shorn of his claimed accomplishments, there is little left to admire.

Filed in: Uncategorized.