The Cook-Peary Files: The “Eskimo Testimony”: Part 5: Donald MacMillan

Written on February 22, 2023

This is the latest in a series of posts that publish for the first time significant documents related to the Polar Controversy.

The only member of Peary’s crew we have not dealt with is Donald MacMillan. The subject of the “Eskimo Testimony” comes up a number of times in his writings over the years. MacMillan outlived all the other members of Peary’s expedition, not dying until 1970. Although most of his relevant published writings are now in the public domain, under the current US Copyright laws, his unpublished writings are protected until 2040. There is little respect for the copyright laws in the digital age, but owning copyrights myself, I do try to observe them, so in the discussion that follows I will only summarize these unpublished writings as to their content, rather than quoting from them directly. For those wishing to see the source materials of these summaries, I will list where they can be found as we go along.

As noted before, MacMillan signed off on the version of the Inuit testimony Peary published in the newspapers in October 1909, and by so doing, tacitly agreed to its accuracy. There is reason to believe that MacMillan may even have witnessed Henson’s questioning of the Inuit aboard the Roosevelt in August 1909, but his own accounts of what the Inuit said vary from Peary’s published account in ways that are hard to reconcile. MacMillan’s accounts are given here in chronological order and summarize what MacMillan said about the route Cook took as related by the Inuit who accompanied him.

First of all, however, we need to get one thing out of the way. MacMillan could not speak Inuktitut, so whatever he recorded had to have come from someone who did, or was derived from what he could understand through isolated word phrases or sign language. Kenn Harper, who wrote a book about Mene, the Inuit boy Peary brought back to America in 1897, and who was married to an Inuk and spoke her language fluently, wrote to me regarding MacMillan’s grasp of the language, which he characterized as “abysmal.” His mother in law, Amaunnalik, who worked for MacMillan on some of his later cruises to the Arctic, often joked about his attempts to speak to the Inuit in their tongue. (letter to the author, dated October 10, 1994).

#1 MacMillan’s 1909 diary: In MacMillan’s diary he says he had questioned “nearly all” of the men Cook had with him once he left land, and that they all agreed that they were never out of sight of land and that they did not spend more than three nights on the sea ice. When they reached the cache they had laid on shore, the sleds were still so heavily laden with food that Cook did not increase his loads from the cache. Along the way they discovered two islands to the southwest of Cape Thomas Hubbard. They were gone such a short time that they found duck and gull eggs “perfectly fresh” upon their return. According to the Inuit, they could have crossed Jones Sound in their boat, but preferred to winter in an igloo. In a later entry he relates that Whitney had told him that Cook had gone beyond Peary’s 1906 record, as Cook had instructed him to do. It should be noted that MacMillan habitually rewrote his accounts, and in fact was the butt of jokes on the Crocker Land Expedition for constantly revising his manuscripts. There are thus several versions of his “diary” and they vary somewhat from revision to revision. This particular version is now at Bowdoin College.

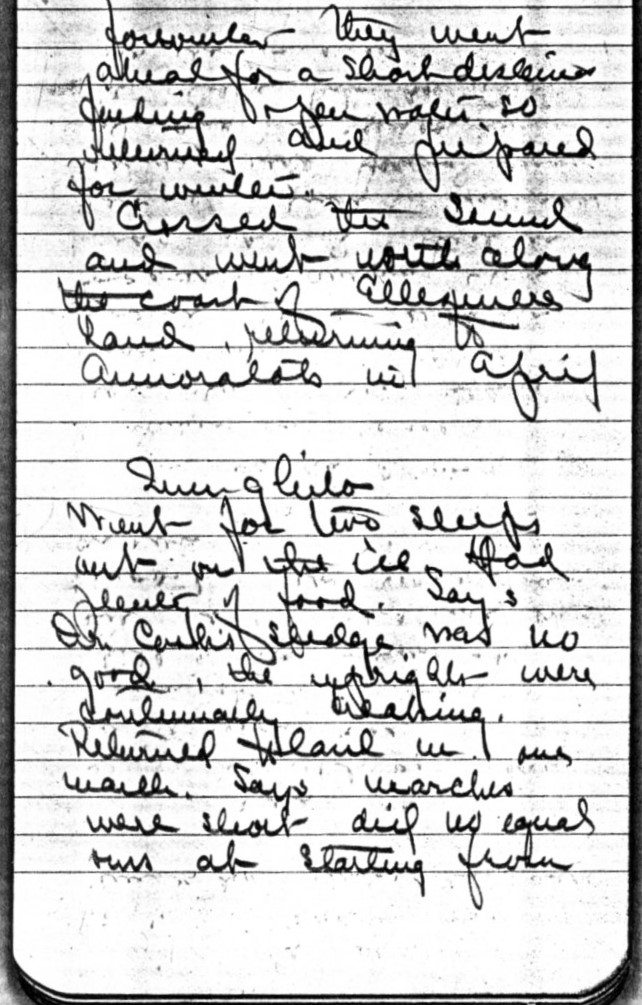

#2 At NARA II is a memorandum in a notebook exactly like the one Peary says he kept on his way to the North Pole and back in 1909. This account is titled “Information about Dr. Cook.” Because it was kept sequestered by Peary with Peary’s North Pole Diary and Borup’s account of the Inuit interviews (see Part 4 of this series), it may have been taken down at the interviews Henson held with the Inuit who had accompanied Dr. Cook.

Sample page from MacMillan’s memorandum

MacMillan says there that Cook left Annoatok early in March with 8 men and 8 sledges, and the last word from him came in the form of the letter addressed to Rudolph Franke, dated March 14 at Cape Thomas Hubbard, that was brought back by six of the Inuit in May, 1908.

It goes on to say that when Cook departed over the ice, he took four Inuit with him. Inugito and Koolootingwah accompanied Cook, Ahwelah and Etukishuk onto the ice for “one sleep,” MacMillan said, before turning back, and they caught up to the others at Shei Island [actually a peninsula]. Although he claims they went only one sleep, MacMillan says they built two igloos on the ice before turning back, implying they stayed with Cook two days. After they left, Cook and his companions encountered “bad ice and open water,” used their ice picks once while on the ice, and returned to land a little west of their starting point. They then went south along the west coast of Axel Heiberg Island, building three igloos before they started using Cook’s silk tent. Along the way they discovered two unknown islands in Crown Prince Gustav Sea. They continued south to Cape Southwest and then to Graham Island in Norwegian Bay before reaching Hell Gate. They reached Jones Sound by way of Colin Archer Peninsula and followed its shores around to Cape Sparbo. From there they went a short distance before finding open water. They then turned back to Cape Sparbo and started building their igloo there for the winter. In the spring they crossed frozen Jones Sound and went north along the east coast of Ellesmere Island, returning to Annoatok in April. They had no meat on the sledges when they left land, and while on the ice saw no bears. They killed none of their dogs to feed the others, made no caches on the ice, and they crossed no leads.

When they returned to the land they visited the cache they had left there, and Etukishuk retrieved his rifle from it. They then went down the west coast of Axel Heiberg Island to a group of small islands shown on Sverdrup’s chart and then crossed the narrow southern end of Crown Prince Gustav Sea to Amund Ringnes Island, then followed down the east coast of that and across Norwegian Bay to Hell Gate. Here they abandoned their dogs, took to their boat and followed round the head & south shore of Jones Sound, but met ice on the inside of Coburg Island. They then went back to Cape Sparbo, where they wintered. In the spring they followed the coast north to Cape Sabine & thence across to Annoatok.

In the same memorandum, MacMillan said Inugito told him they went two sleeps, not one, on the ice and that they always had plenty of food. Inugito said Cook’s sled’s upstanders broke continually on the journey. He and Koolootingwah were able to return to land again after leaving Cook and the others in one march without sleeping. He added that Cook’s marches were short and did not equal the ones he had made while working for Peary in 1906, when he had tried to reach the North Pole from Cape Columbia. He also commented on the abundance of game, noting bears, deer and musk oxen that they killed along the way.

Egingwah, who had only been to the edge of the polar sea with Cook, said the ice near the shore was smooth, but further out it was rough.

Macmillan said that Etukishuk told him he remained on the ice “not more than three sleeps and were never out of sight of land.” He also mentioned camping on a large, uncharted island and that they had seen a second one. He added to the game list that they found, saying plenty of duck and gull eggs were found at Cape Vera, but no hatchlings. Etukishuk said they abandoned their dogs at Hell Gate and took to Cook’s folding boat to cross the straights, and by the time they reached Cape Sparbo, they were unable to cross Jones Sound because of open water.

MacMillan led his own expedition to the Arctic starting in 1913. His goal was to explore the land Peary reported seeing from the heights of Cape Thomas Hubbard, which Peary called Crocker Land. In 1914 MacMillan journeyed about 100 miles out from Axel Heiberg Island to the northwest in search of that mythical land. He had with him on this trip Etukishuk, who had been with Cook in 1908 when he left the same cape. He made several reports of what Etukishuk said about Cook’s trip at that time and also had many opportunities to question the Inuit at his base at Etah during the course of the Crocker Land Expedition, which did not return until 1917. Here are his reports on what MacMillan said he heard at that time.

#3 In a letter to David Brainard dated August 25th 1914, MacMillan said that after they set out to the northwest, they came upon pressure ridges and open leads of water, but after getting through the rough ice near the shore, they had excellent going and covered as many as 30 miles a day, and that he lost sight of the last land at about 75 miles out. In another letter to Thomas Hubbard dated December 11, 1914, he had something to say about Cook. He said Etukishuk told where they had camped on Cook’s outward trip and pointed out a spot on the polar sea that Cook had turned back, which MacMillan estimated was about 15 miles from shore. In this letter he said he had read passages of My Attainment of the Pole to Etukishuk and Ahwelah, who “had many a laugh” over them. ( The Brainard letter is now at Bowdoin, the Hubbard letter is at NARA II.)

#4 MacMillan, in the draft of his book Four Years in the White North, now at Bowdoin, says that at end of the his first march seeking Crocker Land, they camped at the base of a small pressure ridge about 14 miles from land. When asked how far Etukishuk had gone with Cook before turning back, the Inuit looked back toward Cape Colgate and pointed to a small pressure ridge, indicating that as the place they had turned back. When asked where they had gone after that, Etukishuk was supposed to have said they went back to land to get a rifle they had placed in their cache, and then down the south shore and out to a “small island which we found in the ice.” After spending the winter in a rock-sod igloo, they had walked back to Annoatok in the spring. “Here was the same story which he had told to me in the cabin on board the S.S. Roosevelt, anchored at Etah on August 17, 1909!” MacMillan exclaimed. However, when his book was published in 1918, MacMillan left out this entire passage. Nor are there any similar passages to this in any of MacMillan’s original Crocker Land Expedition diaries now at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

#5 After his return from the Crocker Land Expedition, MacMillan sent a letter from Boston to the editor of the American Geographical Society’s journal regarding what the Inuit said about Cook’s journey, which was the most detailed account he ever produced. The letter, dated December 21, 1917, was reproduced in full in The Geographical Review’s February, 1918 number as “New Evidence that Cook did not reach the Pole.” In this account MacMillan said Cook had never actually been to Cape Thomas Hubbard, and that accounted for him not being able to locate the cairn Peary had left there in 1906, which Cook said he had searched for in vain. On the point of land Cook left, MacMillan related, Cook had cached “a few small articles” and departed in the company of four Inuit, who traveled together for one day, during which he covered “about 12 miles.” After competing an igloo, two of the Inuit returned. Cook and his remaining two Inuit did not proceed beyond this point, he said, and after sleeping two nights there, the party returned to the cache on the shore of Axel Heiberg Island, took everything from the cache and proceed south, following its western shore. “Two low islands were discovered in about latitude 79°, very low and about five miles from land.” They then crossed over to Amund Ringnes Island where they killed one or two caribou. From there they went to Cape Southwest, then along the southwest shores of Ellesmere Island, then crossed the land to Goose (Gaas) Fjord and went south to its entrance. There they “turned west, then north into the narrow channel known as Hell Gate” where they abandoned their dogs and one sledge and launched their small collapsible boat. They followed along the southern shore of Jones Sound to Baffin Bay where they encountered heavy ice that stopped their progress. They then turned back to Cape Sparbo, where they prepared an old Inuit igloo for the winter. Game was plentiful and the igloo, well stocked with meat, was warm and comfortable. In the spring, manhauling their sled, they crossed Jones Sound. Between Coburg Island and Ellesmere Island they discovered two small islands, and after much privation, they crossed Smith Sound and reached Annoatok.

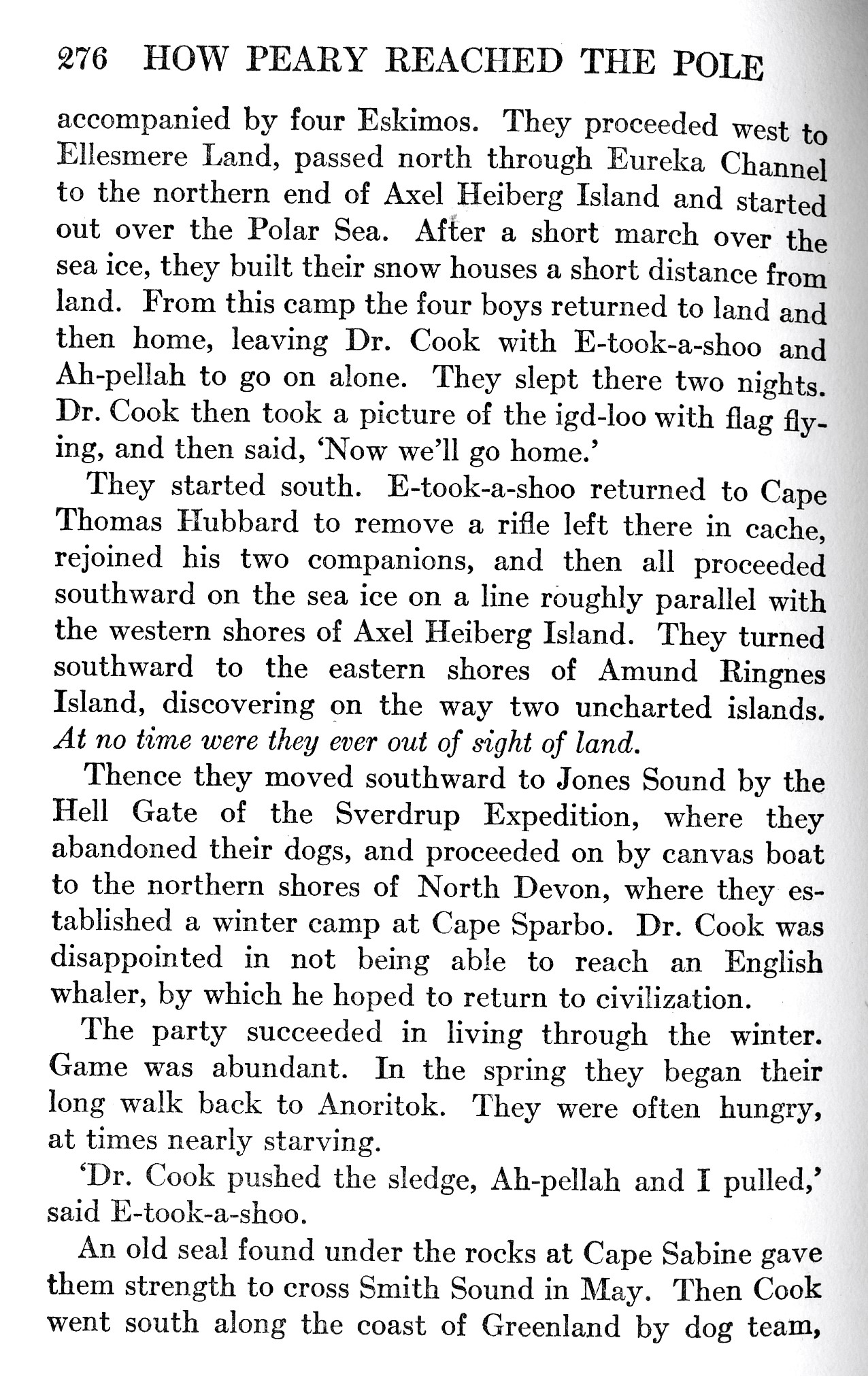

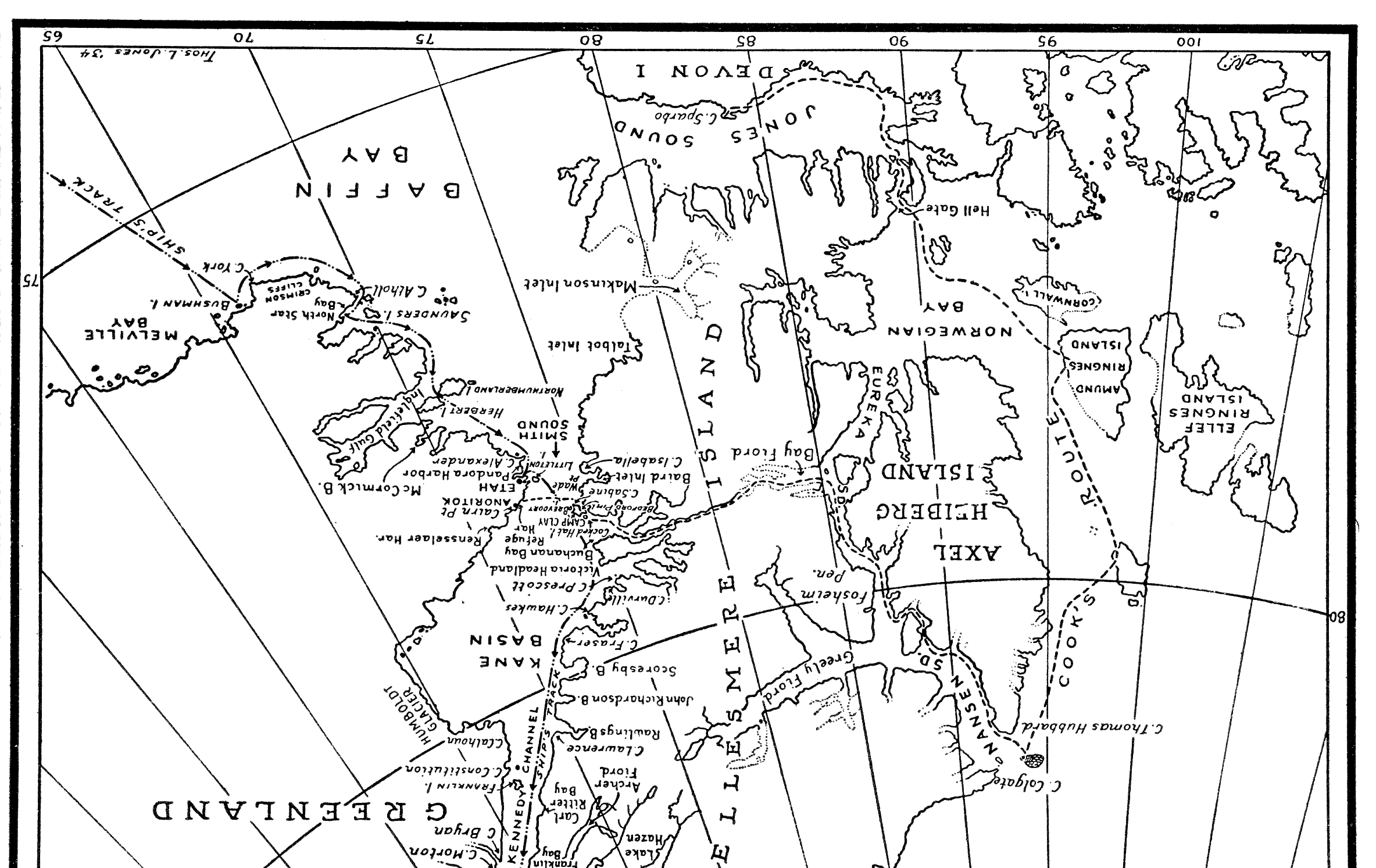

#6 In his 1934 book, How Peary Reached the Pole, MacMillan had yet another go at it; here is the relevant page: “With Dr. Cook [the Inuit and Franke] left Anoritok in the early spring,

with the intention of catching the first steamer for Copenhagen.”

Again, this version differs in some details from MacMillan’s previous accounts. On the end papers of this book he published a new map showing Cook’s alleged route according to his Inuit companions. The route on this map is very different from the one published by Peary.

So what is one to make of all of these various MacMillan accounts? If one reads the different accounts and compares their details, one soon realizes they are not, as MacMillan claims, “the same story which he had told to me in the cabin on board the S.S. Roosevelt, anchored at Etah on August 17, 1909!” They differ from Peary’s version in many significant ways, and from each other for that matter, as to the distance Cook traveled on the ice, the time the two extra Inuit spent with Cook’s party, the time Cook, Etukishuk and Ahwelah spent at the igloo after the other two Inuit returned, the direction in which Cook’s party moved once they broke camp, where they made landfall, and what they took from the cache they had left at Cape Thomas Hubbard upon their landfall. MacMillan even questions if Cook ever was at Cape Thomas Hubbard at all in one of them, which Peary’s version accepted without question. Then there are also differences in the accounts of their return trip: the size and location of the two islands they sighted, for instance, is very different in the various accounts, and Cook’s route varies from Peary’s published 1909 map, allegedly drawn by his Inuit. A more detailed accounting of all these differences will be made once we have considered the two accounts of what Knud Rasmussen says he heard from Inuit in Greenland in 1909.

Filed in: Uncategorized.