The Cook-Peary Files: The “Eskimo Testimony”: Part 7: Knud Rasmussen 1

Written on April 11, 2023

This is the latest in a series of posts that publish for the first time significant documents related to the Polar Controversy.

Knud Rasmussen first visited the Polar Inuit in 1902 as part of the Danish Literary Expedition sent out to study Inuit culture. He was part Inuit himself, and would spend a lot of time north of the permanent Danish settlements in Greenland after that. In 1910 Rasmussen and Peter Freuchen would establish the Thule mission and trading post at North Star Bay, 20 miles up the coast from Cape York, to take advantage of a lucrative fur trade with the Polar Inuit farther north. But even by 1909, Rasmussen had already become something of a Danish folk-hero. As Captain Shoubye said, “We believe in Knud Rasmussen because he is more of an Eskimo than a white man, and he knows all the tricks of the ice.”

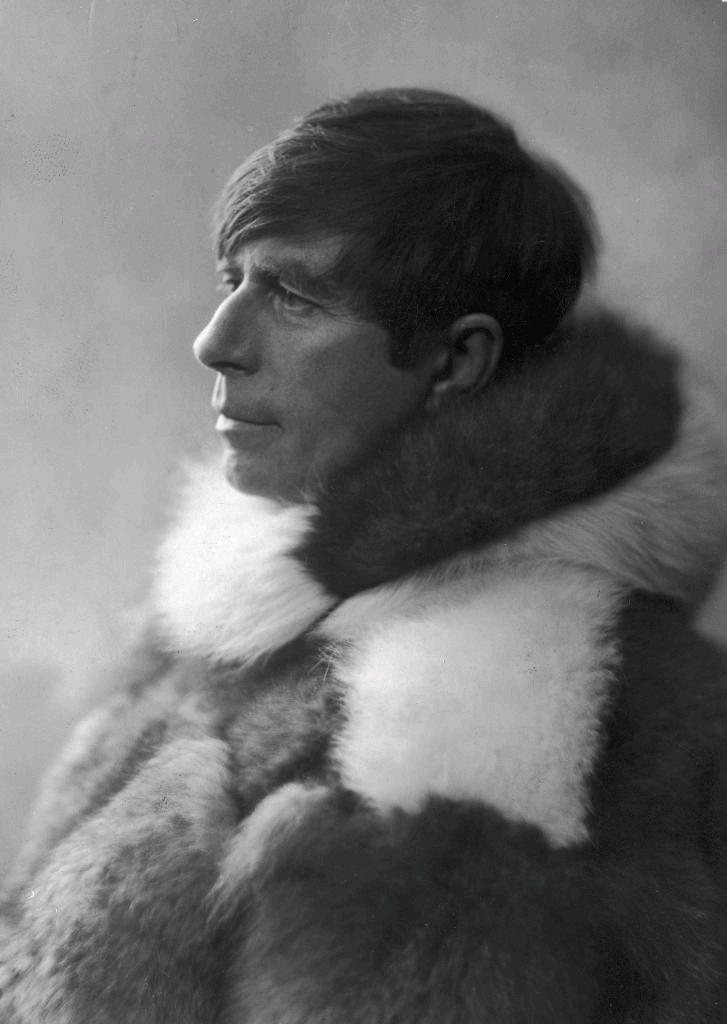

Knud Rasmussen

Rasmussen had first met Cook at Etah when John Bradley’s yacht had called there in August 1907. Cook was mum on any plan to essay the North Pole at the time, so Rasmussen had taken him for no more than Bradley’s private secretary. Cook invited him to dinner aboard the John R. Bradley, but his millionaire backer could not abide the smell of him and banished him to the galley. Nevertheless, over the winter, Rasmussen amiably visited with Cook several times and learned of his preparations to attempt the Pole, and later remarked, “I had the opportunity to ascertain that a more sensibly equipped expedition could not possibly be thought of.”

Like the Swiss, in the spring of 1909, Rasmussen, too, heard the talk of Cook’s triumph while he was in Umanak Fjord after Cook had passed south on his way to Egedesminde. On July 16th, just before leaving on the Godthaab for North Star, he wrote a letter to Cook:

My most hearty congratulations to you on your successful voyage to the North Pole. You have won the victory, and this victory, the greatest in Arctic history, will, in spite of all the honours which will overwhelm you from the whole world, be the greatest remuneration in itself. Your display of energy has been wonderful, and I admire you deeply. But it is well known that all great victories produce envy, and you certainly know that you will have to fight a bitter battle against all the sceptics in the world. I have, therefore, thought that I perhaps might help you, if I, during my stay this summer among the Eskimos at Cape York, had a serious interview with your followers and later published that interview. For the construction of this interview, I would be much obliged if you would send me a small sketch of your travel before you leave Greenland, and I ask you to send it to me at Umanok with “Hans Egede.”

During Rasmussen’s stay that summer at Cape York, he did not interview either of Cook’s Inuit companions on his journey toward the Pole, who remained farther north. But he heard a lot about it from other members of their tribe, though he admitted freely that what he heard was, therefore, “second-hand.” When the Hans Egede called at Umanak, Rasmussen was disappointed that it bore no message to him from Dr. Cook. He did not do much better getting details of Cook’s journey from him when he met Cook personally at Egedesminde just before the ship sailed. Therefore most of the details of Cook’s journey only reached him through newspaper accounts that he received by mail from Denmark dated up to September 9. In them Rasmussen discerned exactly what he had predicted in July: the beginnings of the controversy over whether Cook had actually reached the North Pole. He therefore thought the time was right to say what he had learned of Cook’s journey during his stay at North Star Bay that summer. He sent his account, dated September 25, to Politiken, where it was published on October 20.

Right at the beginning, Rasmussen admitted that what he had to convey was not “proof” of Dr. Cook’s attainment: “Of course it is impossible to get absolute proofs that Dr. Cook—one white man with two young Eskimos—has been at the North Pole. It must be more of less a matter of faith, as most authorities can maintain that a traveler, even if he does not reach the pole-point, can make observations, which, in the absence of real observations, cannot be overthrown. . . The Polar-Eskimos are incapable of stating positively whether Dr. Cook has been only on his way towards the Pole or really has reached the famous 90 degrees . . . .

“As stated above, I have not met the companions of Dr. Cook, but I am informed by trustworthy members of the same tribe, that the expedition had, on the whole way out, comparatively very favorable ice and good weather. The ice got better and better the farther out they went. . . How far they have been, they have, of course, not been able to decide; but they have said that their journey across the ice fields, away from land was so long that the sun appeared, reached a high point in the sky and at last did not set at all, and it was almost summer before they reached land again. . . .

“The Eskimos . . . have themselves shown me on my own map the route of the expedition towards the North Pole and the winter camp at Jones’ Sound. . . Besides, the Eskimos have told me in full accord with Cook’s reports, how Apilok and Itukusak stated that they could not on their return journey go to Heiberg’s Land, where they had their [caches]. . . because of cracks in the ice, and this was the reason why they passed down to North Devon. . . .

“The Eskimos stated decisively that they were very much astonished when Cook told them that they now had reached their goal, because the place was not at all different from the other ice over which they had traveled. . . so it is sure that the travellers were not compelled to turn back because of ice-hindrances, but only because they believed the goal was reached. . . .

“Briefly: It was the Eskimos’ opinion that Cook has been at the Pole, and that he, according to the statement of his companions, during the whole journey had shown unusual strength and energy.”

Rasmussen concluded as he began: “As I remarked before, the above is a subjective proof that Cook has been at the Pole.”

In an interview printed in Zum Dannebrog on October 26, Rasmussen continued this qualified stance: “Well * * * you will understand that I have not made any proof; and who could make it? The two Greenlanders from Etah could not, even if I had spoken with them. They do not understand anything about observations. But the Greenlanders have a remarkable sense of taking bearings. They can judge correctly from the fatigues experienced and the number of nights spent on the way; and when they do tell their brothers of the tribe about the immensely long journey with Dr. Cook, they must have travelled very far.”

When asked about Peary, Rasmussen said, “I do not know much besides the fact that he insists that Cook has not been far from land. And that is nonsense. If the expedition had only been a few days journey from land, why should they have come to Cape Sparbo for the winter? And the expedition has been there.” Rasmussen laid great emphasis on this: “Personally, I wish to express my admiration for the bravery and firmness Dr. Cook has shown on his Polar trip,” he had said in his previous statement. “This man who practically alone has gone through and endured the winter at Cape Sparbo and the terrible march up to Anonitok through deep snow and violent ice-crushings, in darkness and bitter cold, has deserved to be the first man at the North Pole.”

Rasmussen thought the matter might be cleared up entirely by the instructions he had given to a missionary at North Star Bay named Hans Olsen when Rasmussen returned there without meeting Ahwelah or Etukishuk. Rasmussen described Olsen as “a very intelligent man, who will not be in doubt about what it depends upon, and he is better able than I to win the confidence of Dr. Cook’s two Eskimos.” Olsen was a Greenlander, himself, and although he spoke Kalaallisut, a different dialect than that of the Polar Inuit, Rasmussen had asked him to interview the pair and send him a report. “The first mail from him will bring the results of his examinations,” Rasmussen said, adding confidently, “Dr. Cook will, no doubt, stand the test!”

Sources: All of the quotations from Politiken and Zum Dannebrog are from the translation published in an article entitled “The Witnesses for Dr. Cook,” by the then United States Minister to Denmark, Maurice Francis Egan, which appeared in The Rosary, v. xxxv, no. 5 (November 1909), which contains Rasmussen’s full written statement to Politiken. A very similar account appeared in the pages of the New York Times on October 20, 1909.

Filed in: Uncategorized.