The Cook-Peary Files: The “Eskimo Testimony”: Part 19: New Evidence from the AGS Archives

Written on November 12, 2024

This is the latest in a series of posts that publish for the first time significant documents related to the Polar Controversy.

The evidence concerning “The Eskimo Testimony” was the subject of this blog for more than a year and ran to 18 parts, concluding with the post for April 2024. Since then the digitized holdings of the Archives of the American Geographical Society, which are posted by the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, have yielded some interesting new evidence on this subject.

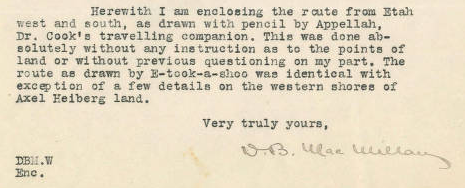

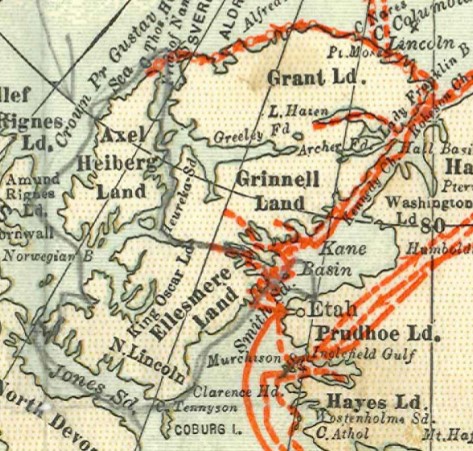

The first item is a copy of a letter from Donald MacMillan, dated January 28, 1918, sent to the editor of the Geographical Review concerning the proofs of an article eventually published in that journal under the title “New Evidence that Dr. Cook did not reach the North Pole.” (see the post for February 22, 2023 below). MacMillan makes comments on the copy and suggests changes. Incidentally, he confirms in the letter that the cameraman, Edward S. Brooke, “was sent by Cook to watch me and get certain information of his own.” The letter encloses a colored map of “The North Polar Regions” published by R.D. Servoss of NY. This map can be dated to between 1907 and 1909 because, although it shows “Crocker Land,” which was not named until Peary’s Harper’s article was published in 1907, it does not show Peary’s alleged route to the North Pole in 1909. MacMillan has penciled this notation on the map: “Track of Dr. Cook as drawn by Ah-pellah, his companion, on April 18, 1917,” and in his letter provides this additional information:

An enlargement of Ahwelah’s penciled in route from the map is reproduced here:

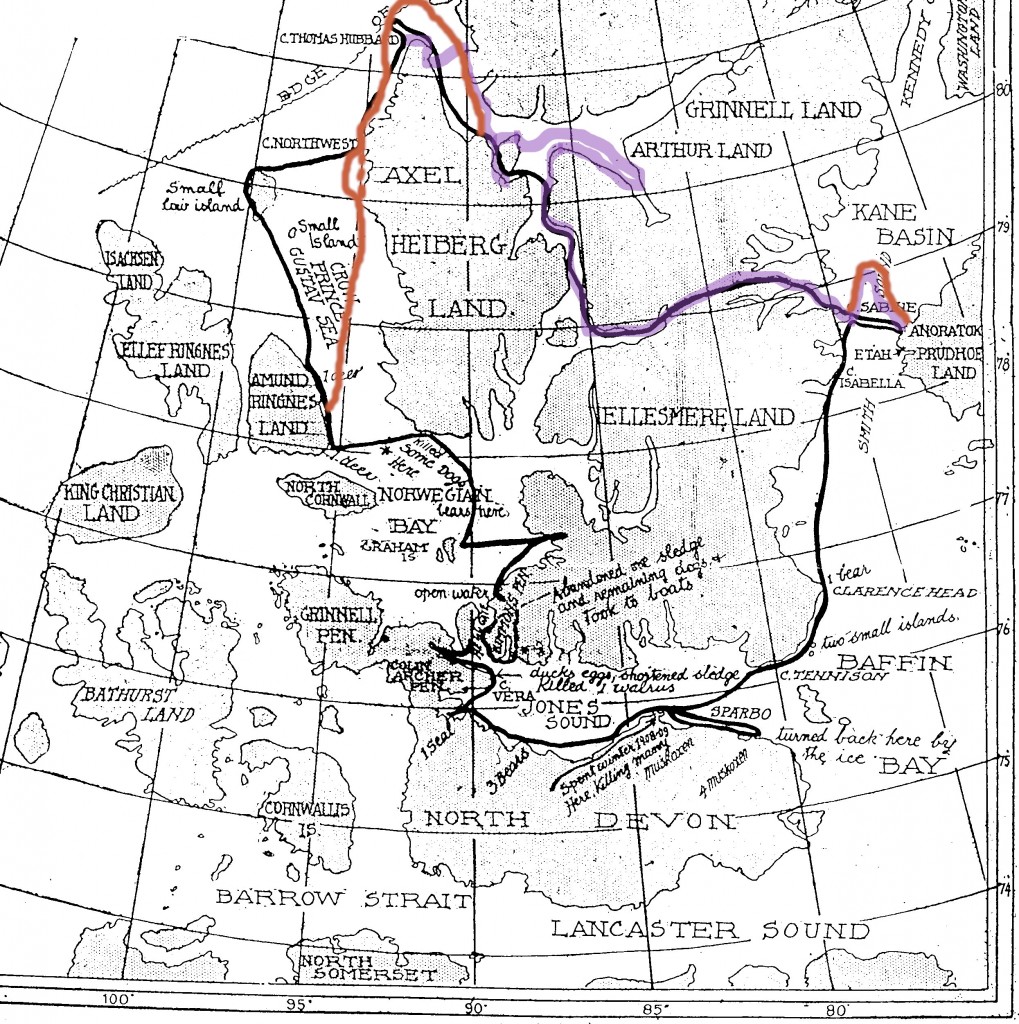

For comparison, here is a copy of the map published by The Peary Arctic Club in its copyrighted story on October 13, 1909, showing the route of Dr. Cook that was penciled in by Dr. Cook’s other companion, Etukishook, under questioning fro Matt Henson at Etah on August 17, 1909.

Etukishook’s route is show on the map in black. Dr. Cook’s actual route up to the time he reached Cape Thomas Hubbard, as indicated in his original 1908 notebook kept on his polar attempt, is shown on this map in purple. Ahwelah’s route, where it differs from the Peary map’s route has been indicated in orange. A comparison of the three routes brings up some interesting points.

Etukishook’s route is show on the map in black. Dr. Cook’s actual route up to the time he reached Cape Thomas Hubbard, as indicated in his original 1908 notebook kept on his polar attempt, is shown on this map in purple. Ahwelah’s route, where it differs from the Peary map’s route has been indicated in orange. A comparison of the three routes brings up some interesting points.

Notice these differences in relation to the routes: First of all, each of the two Inuit routes show the same route as far as reaching the east coast of Axel Heiberg Island. This is notable because Dr. Cook did not follow this route. According to his original notebook he did not travel through “Flat Sound” to reach Nansen Sound, but took a detour into Greely Fjord and then Cannon Fjord to lay caches for his return and then went straight across from Greely Fjord to the northern tip of Shei Island, later found to be a peninsula, then down its west coast to reach Flat Sound. Although this is made quite definite in his notebook, and Cook even admitted that he had laid caches so he could return via Cannon Fjord in his book, My Attainment of the Pole, (page 203), neither Inuit map shows this diversion. The Peary map then shows him going up the east coast of Axel Heiberg Island to reach Cape Thomas Hubbard, from which Cook departed on his attempt to reach the North Pole. However, Ahwelah’s route shows something quite different in this regard from Etukishuk’s.

It shows Cook crossing over Nansen Sound and going up the west coast of Ellesmere Island instead, which is what Cook’s notebook indicates he did, but it does not show him crossing back to Axel Heiberg Island’s east coast, even though he published a picture of the distinctive cliffs below which he camped there. Instead, Ahwelah shows him continuing all the way to the end of the Kleybolte Peninsula, then thought to be an island, which lies at about 81° 75’ N before turning west and rounding the entire tip of Axel Heiberg Island without touching land again until he reaches Cape Northwest. Neither Cook’s actual route, nor Peary’s map confirms this. In fact, it is in direct contradiction to what Peary said Cook did in the statement that accompanied the map published on October 13, 1909.

From Cape Northwest, Ahwelah’s penciled route diverges: one line (dotted in orange) goes straight down the west coast of Axel Heiberg, the other bulges out slightly in the direction of Meighen Island, which is not shown on the colored map. However, the “bulge” does not go nearly far enough to the west to reach the location of the then unknown Meighen Island, which appeared on the Peary map and which lies just inside the intersection of the first longitudinal and latitudinal lines to the left of the bulge at about the head of the arrow drawn by MacMillan on the colored map. On the Peary map, the route goes all the way around Meighen Island, then straight down to the top of the east coast of Amund Ringnes Island to the south, and then along its east coast before turning east to cross over to Ellesmere Island again. However Ahwelah’s route, as MacMillan admits above, shows something quite different. It goes right down the west coast of Axel Heiberg before crossing over to the middle of the east coast of Amund Ringnes Island. The rest of the route from there to where Cook wintered at Cape Sparbo in 1908-09 is very similar on both the Inuit maps, and again from Cape Sparbo until the return course reaches Cape Sabine the next spring. Peary’s map shows a straight line crossing of Smith Sound from there to reach Annoatok, whereas Ahwelah’s shows a significant northern diversion before reaching Cook’s winter base, mirroring Cook’s actual route as accounted for in his notebook.

So, like the other accounts attributed to Cook’s two Inuit companions, Ahwelah’s route map is itself inconsistent in many details with these other accounts. It confirms Cook’s route after reaching the east coast of Amund Ringnes Island as depicted on Peary’s map, and also Cook’s northern diversion from Cape Sabine to arrive again at Annoatok in 1909, but it contradicts Cook’s actual route up to that point he reached Cape Thomas Hubbard, and it also fails to coincide with Peary’s map from the time Cook reached the east coast of Axel Heiberg Island until he landed on Amund Ringnes Island. It also fails to confirm the diversion from Cape Northwest to Meighen Island, as shown on Peary’s map, or the route from there to Amund Ringnes. Being confirmatory in some respects but contradictory in others does not make the Ahwelah map positive or negative evidence toward deducing the exact truth, and it adds nothing at all to the question of how far Dr. Cook was from land at the time he turned back from his failed attempt to reach the North Pole.

However, Ahwelah’s route, drawn eight years after the Etukishuk’s may account for the later oral tradition accounts of Cook going up the coast of Ellesmere Island and reaching about 82° N there (see post for September 14, 2023 below). It being the “last” oral account given by one of Cook’s companions, it may have then been the one enshrined in the tribe’s folk memory. However, the discrepancies shown on Ahwelah’s route might be attributed to an eyewitness’s statement that the Inuit could be quite confused as to where they were and in what direction they had traveled once out on the drifting pack ice.

This suggestion comes in the form of several letters and newspaper interviews contained in the AGS Archives from Dr. Thomas Dedrick. They were given in 1926 in the wake of the disclosure of the murder of Ross Marvin by Kudlooktoo on his way back to shore as part of one of Peary’s advance relay teams on his attempt to reach the North Pole in 1909. Dedrick was no friend of Peary’s. They had gotten into a bitter dispute on Peary’s 1898-02 expedition, on which Dedrick had been Peary’s surgeon. But his opinion does not seem to be in spite of Peary, and he makes no accusations against Peary, as some have, in regard to the murder. His statement is based on his own experience with Inuit he accumulated during his five-year stay in the Arctic. It was common knowledge, Dedrick said, that once on the drifting pack the Inuit were easily disoriented as to direction. In fact, he said he believed that the Inuit had murdered Marvin because they were convinced that he was leading them in the wrong direction, away for land instead of toward it. This, however, does not account for Marvin’s two Inuit companions safely making landfall after he was killed.

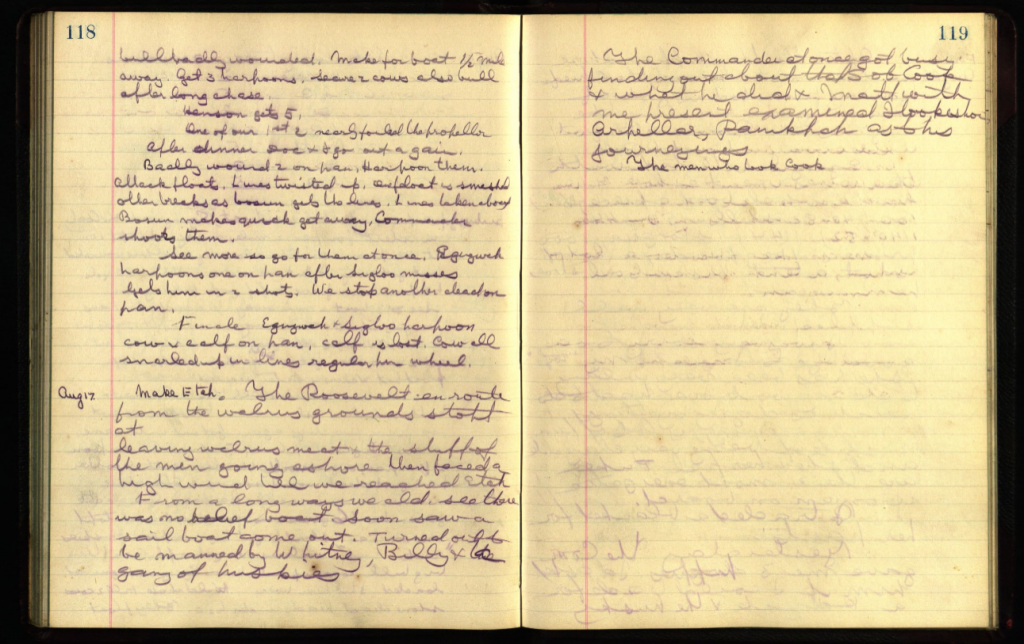

Other relevant evidence in the Archives comes in the form of the entry for August 17, 1909 in George Borup’s diary, also among the holdings of the AGS.

The relevant part of the entry at the top of page 119 reads: “The Commander at once got busy finding out about that S.O.B. Cook & what he did & Matt with me present examined Itookishoe, Arpellar, Panikpah as to his journeyings.” There the entry ends, picking up after a long blank space with an entry dated August 20. The small words “The men who took Cook” written below the August 17 entry are the first words from that entry, written in Borup’s regular sized handwriting on the following page. This entry confirms our supposition that it was Matt Henson, alone, who interviewed Cook’s Inuit companions in 1909, with Borup there to write down what they said (see the post for January 27, 2023 below).

Finally, the AGS Archives also contains the logbook of Bob Bartlett. However, he makes no mention of the Inuit interrogation under the appropriate dates.

The AGS Archive may be viewed at https://uwm.edu/lib-collections/ags-ny/

Filed in: Uncategorized.