The Cook-Peary Files: Peary’s Immaculate Notebook

Written on February 3, 2025

This is the latest in a series of posts that publish for the first time significant documents related to the Polar Controversy.

In February 1910, a bill, eventually known as the Bates Bill, was introduced in Congress proposing that Robert E. Peary be given the Thanks of Congress and retired with the rank of Rear Admiral in the Civil Engineer Corps for his discovery of the North Pole. The bill passed the Senate without opposition, but not so in the House. The recent demise of Dr. Cook’s claim and objections by many line officers in the Navy, who pointed out that only the Chief of the Bureau of Docks and Yards was allowed that rank-equivalency for protocol purposes in the Engineer Corps, caused the bill to be sent for consideration to the House Committee on Naval Affairs.

In March, Peary was summoned to testify, but instead sent a personal representative in his place to say that the request of the Committee to see his original records could not be granted because it would compromise his contract with his publisher, to whom he had sold the exclusive rights to his book-length narrative of his polar conquest, and who now had in preparation. This request had been occasioned by the testimony before the Committee of Henry Gannett, one of the select committee members appointed by the National Geographic Society to examine Peary’s records. After that examination, the Society, of which Gannett was now the President, unanimously certified that Peary’s records, including his original notebook kept on his journey toward the Pole, proved he had reached the North Pole on April 6, 1909. Gannett’s testimony, however, indicated that the Society’s examination had been perfunctory, at best, before they rendered this judgment. So, the Committee members wanted to see Peary’s “proofs” for themselves. Without Peary’s personal testimony and an examination of his original records, the Bates Bill was tabled, and the Committee adjourned.

Therefore, Peary had no choice, so he personally appeared before the Committee in January 1911. His testimony included a number of statements that skeptical committee members felt raised doubt regarding his polar claim. Peary had been compelled to turn over the polar notebook that he said was the original he had kept on his successful journey to the North Pole, but some of its physical features made one committee member skeptical of its authenticity.

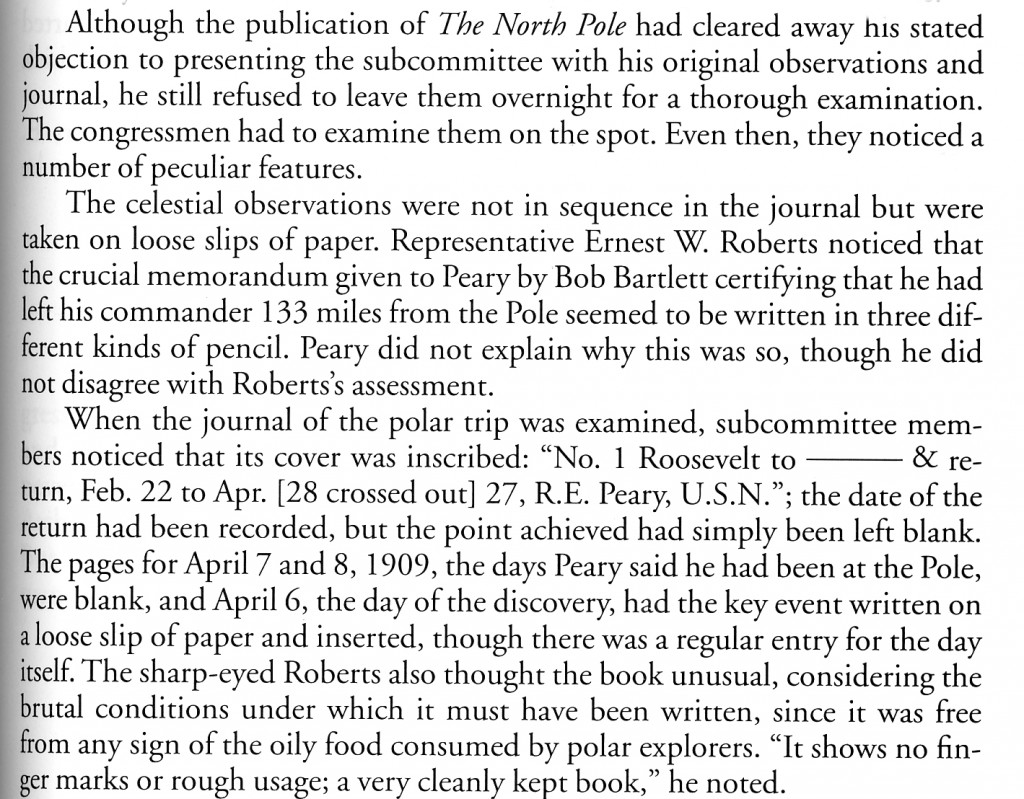

As I described them in my book, Cook & Peary, the Polar Controversy Resolved:

Once out of committee, the Bates Bill was bitterly opposed by Representative Robert B. Macon of Arkansas, who said in a speech from the floor during the bill’s debate that he had devoted many hours of study to the matter and believed Peary’s claim to be “a fake pure and simple.” One of the factors that convinced him of this was the immaculate condition of Peary’s alleged original notebook:

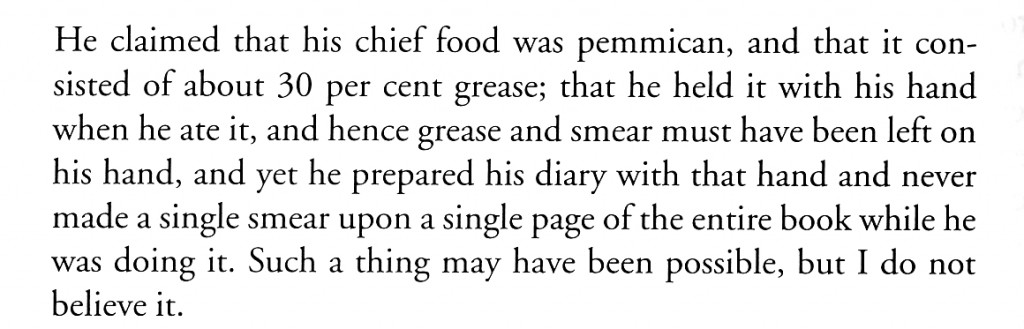

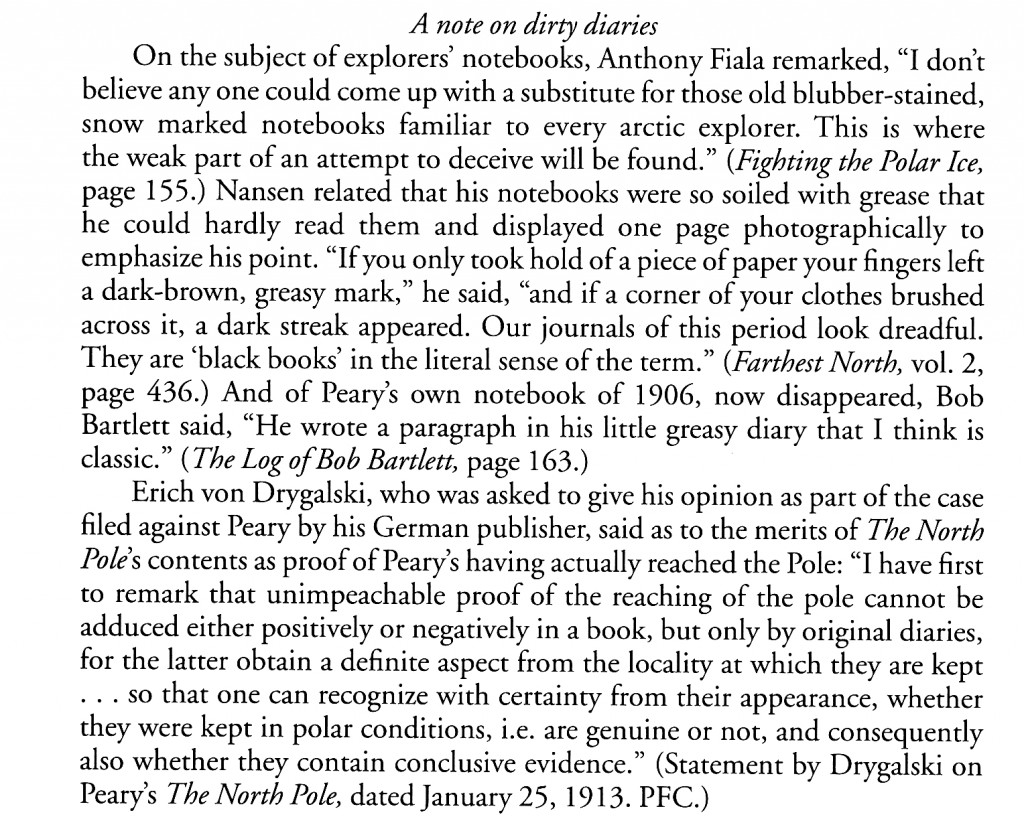

Many imminent explorers who had experience with keeping records under polar conditions would have agreed with Macon. As I explained in Cook & Peary:

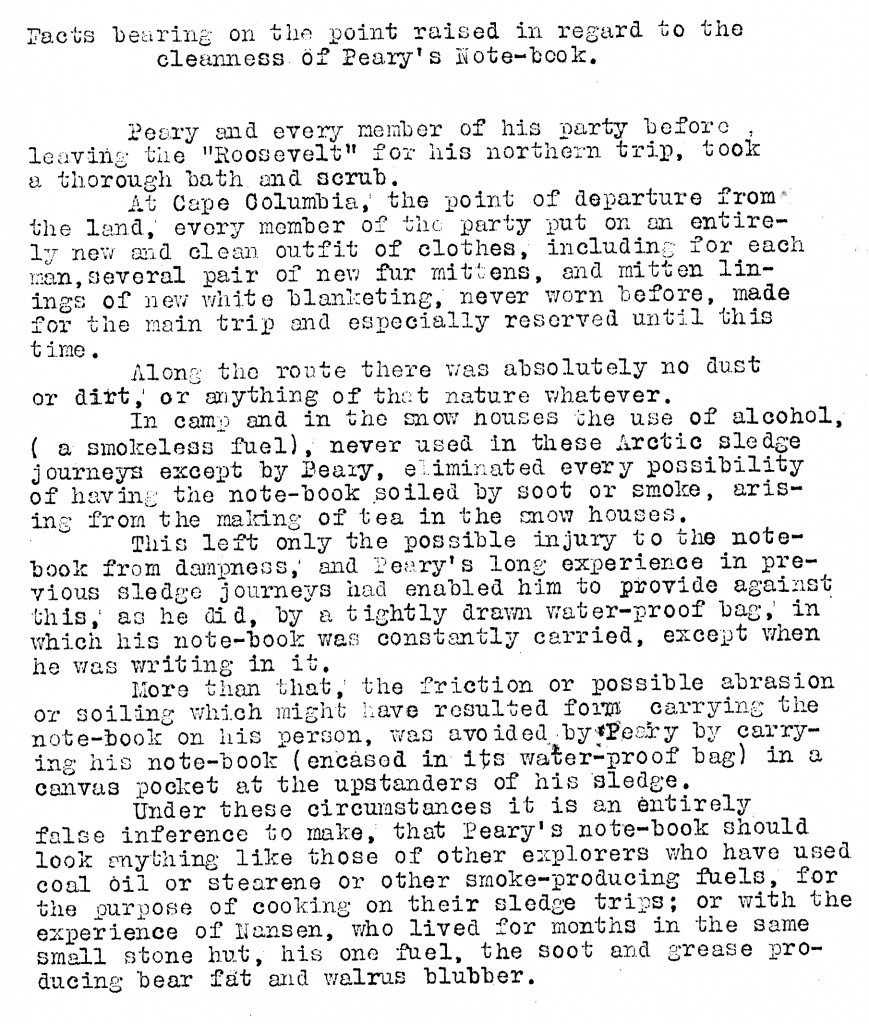

Peary was prone to keep personal memoranda of any criticisms made of him. The questions concerning his notebook’s condition were no exceptions. In response to the doubts raised, he wrote a statement that sought to justify why it was undeserving of the doubts of Macon and Roberts. I came across this memorandum while doing hundreds of hours of research in Peary’s papers preserved at the National Archives in the 1990s. I noted it in my book, where I described it as “not very convincing.” Here it is in full, published for the first time anywhere:

In 1989, Arthur T. Anthony, a expert document examiner with the Division of Forensic Sciences, Georgia Bureau of Investigation, made a limited examination of Peary’s notebook in May 1989. He concluded that the notebook could not have been written under the conditions described by Peary and was “not a chronicling of events that were happening when the journal was written.” The most interesting thing Anthony noted was that the two loose sheets inserted in the diary, one containing Peary’s famous entry on his arrival at the pole, “The Pole at Last!”, were consecutive pages out of single signature because the halves of the single watermark on the two sheets matched perfectly, yet they were placed in two different signatures in the bound notebook, leading him to conclude that they were not original entries, but were placed there after the fact.

Furthermore, Peary, who was right-handed, was in the draftsman’s habit of holding his pen between his index finger and middle finger. Wearing mittens would therefore have made writing with his normal grip impossible, yet the notebook is in his characteristic hand, slanted left, and is, in fact, far neater than many of his ordinary letters, presumably written at his leisure in comfortable surroundings.

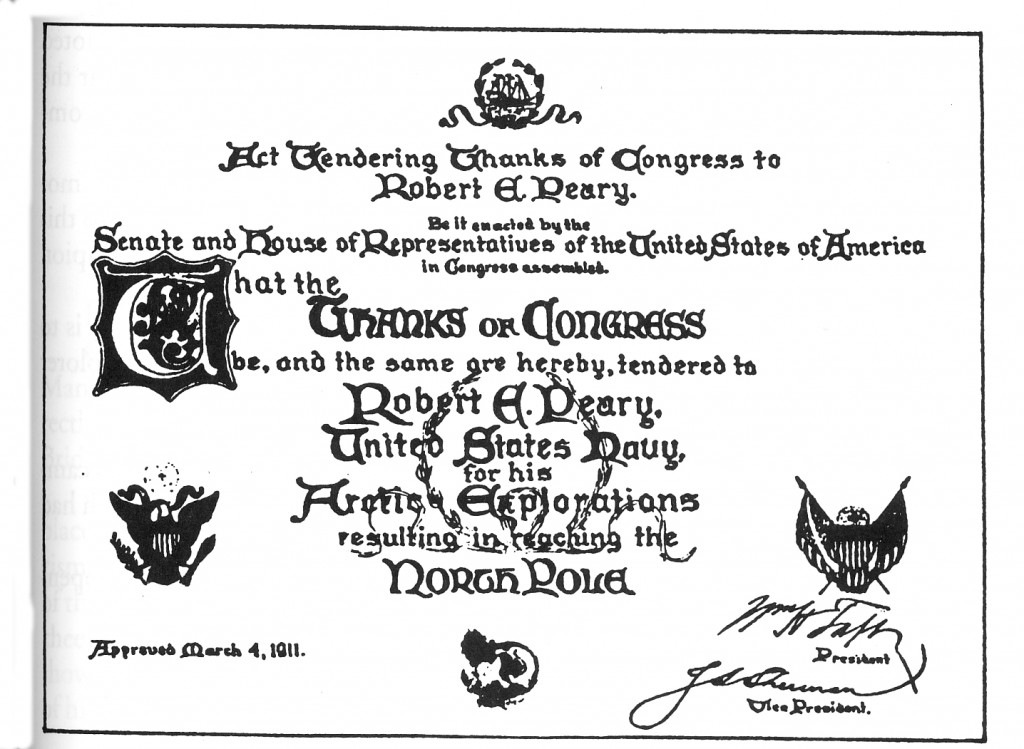

After bitter remarks by Representative Macon from the floor of the House, the Bates Bill passed, and Peary was retired with the rank of Rear Admiral in the Engineer Corps. He also received the Thanks of Congress, but curiously, it was given for “Arctic Explorations resulting in reaching the North Pole,” not for discovering it.

Congress also failed to award him the gold medal proposed in the original bill that passed the Senate in 1910. This may have been due to the many doubts raised by Peary’s own testimony and the peculiarities of the notebook he said proved that he had. Indeed, his testimony in 1911 was the beginning of the increasing doubts about his claim that have today denied him the unequivocal title, Discoverer of the North Pole.

Peary’s memorandum is among the Peary Family Papers, Record Group XP, at NARA II, College Park, MD.

Anthony’s analysis of Peary’s notebook was published in: Journal of Forensic Sciences, vol. 36 [1991] 1614-24

Filed in: Uncategorized.