The Cook-Peary files: October 15, 1909: The Parker-Browne testimony, part 2

Written on January 7, 2018

This is the 8th in a series examining significant unpublished documents related to the Polar Controversy.

The lecture Parker refers to took place on December 7, 1906. Cook’s claimed success in Alaska led to his election as the second president of the Explorers Club later that year. Parker makes much of Cook having a silk flag. This seems trivial, after all, his explanation isn’t implausible, or perhaps he took it along, “just in case.”

Things to note in this section:

-

Browne asserts that Cook “went over the Eastern Ridge.” This is actually what Cook believed the route he described did, but it was not the ridge that Parker and Browne attempted in 1912. Both Cook and Parker-Browne later referred to their routes as along “the Northeast Ridge,” now known as Karsten’s Ridge. That would not be accurate for Cook. It seems that Cook always confused the two separate ridges and believed they were one and the same. That is the only way to explain his various descriptions of his own fantasy route.

-

Notice that here, Parker, who has previously said it was “perfectly understood” that Cook would make no further attempts on the summit that season, now says he was “under the impression, however, that he did say so, but I cannot say definitely.” Browne, however, testified that Cook said he would “absolutely do no climbing whatsoever.” In fact, Parker seemed aware that Cook fully intended to make a reconnaissance of the mountain before heading for home, and testifies that Cook “announced” such a plan if his financial sponsor, Henry Disston didn’t come up.

-

Parker makes a case against Cook using both his “summit” photo and his lack of other photos of his approach to the summit or surrounding peaks as evidence that he never made the climb. These are all valid points, but at that time didn’t prove the climb wasn’t made. Every one of Cook’s photos, both published and unpublished, alleged to have been made during his climb, can now be identified today as having been made within the confines defined by Barrill’s affidavit. At the time of Parker’s testimony, however, none of them had been so identified.

-

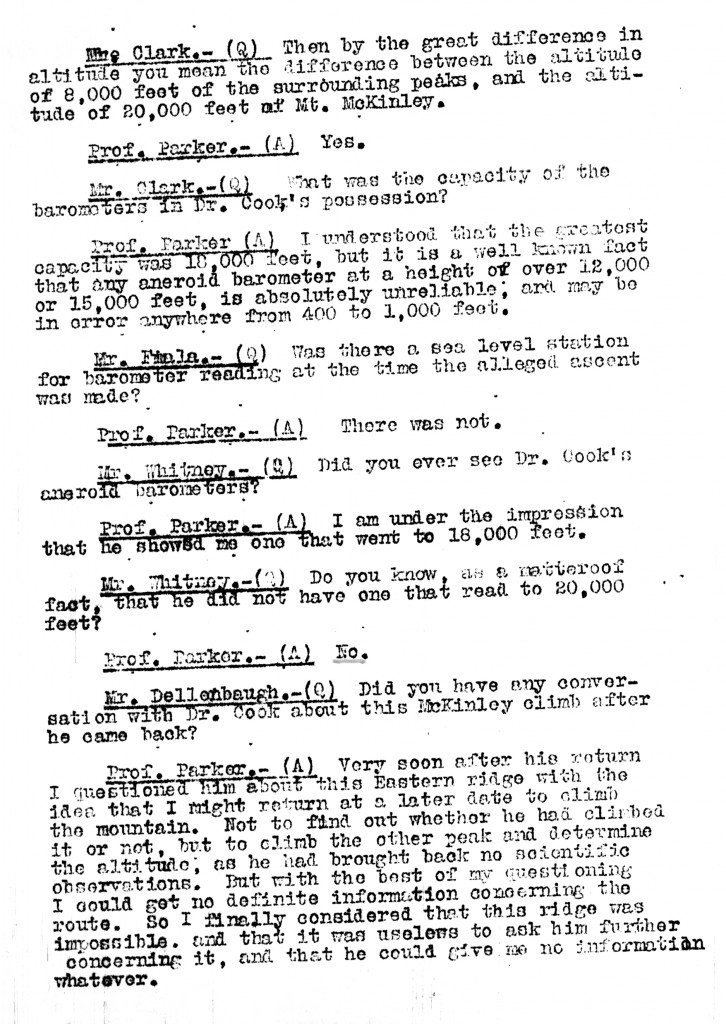

Parker argues that Cook’s estimate of the summit’s elevation of 20,390 feet is worthless because it was his “impression” that Cook had no equipment that could measure such a height. However, Cook’s estimate was more accurate than that published by Parker-Browne after the 1912 expedition on which they are credited with coming within 464 feet of the summit before turning back. They estimated the height at 20,450 feet. The actual height of Denali is 20,310 feet, only recently corrected from 20,320 feet.

-

Although there was not a “sea level station for barometer reading,” John Dokkin was charged with keeping a record of the barometer readings at a known height, where he returned after parting with Cook and Barrill on Ruth Glacier. This would act as the check on the accuracy of any readings Cook took on the mountain that Anthony Fiala was referring to.

-

Notice that Parker again is uncertain when asked directly if Cook’s barometers were adequate. When asked: “Do you know, as a matter of fact, that he did not have one that read to 20,000 feet”? His answer was “No.”

-

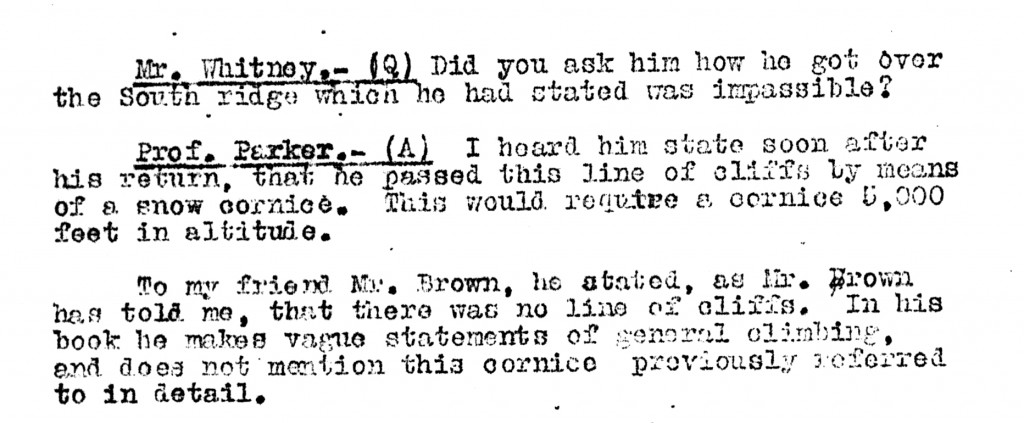

The discussion concerning a “South Ridge” is confusing. Cook’s climbing directions don’t mention such a ridge in his published account, To the Top of the Continent, though they are vague, indeed, and have led many to conclude that they are impossible to reconcile with actual terrain, though others believe they are.

At the end of his testimony, Belmore Browne makes an opening statement. This will be the subject of the next post.

Filed in: Uncategorized.