The John W. Goodsell Archive: Part 1 of 3

Written on September 29, 2019

Dr. John W. Goodsell was the surgeon to Robert E. Peary’s 1908-09 expedition aimed at the North Pole. Unlike Peary’s previous expedition physicians, Goodsell participated in the field in Peary’s attempt to reach it, but in the end, like all the others but one, Peary fell out with him after the expedition returned. The differences between the men arose over Peary’s restrictions on Goodsell’s ability to lecture and publish his own account of the expedition based on his diary, even after Peary had released all other members of the expedition from their contractual obligations to wait until Peary’s own account was in print.

During the course of my research for Cook and Peary, the Polar Controversy, Resolved, I did not visit the Goodsell collection in Mercer, PA, although I was aware of it. This was due to the fact that Goodsell was a peripheral figure in the controversy, and because the Peary Family Papers preserved at the National Archives had at least a partial copy of Goodsell’s diary that covered the incidents and dates it contained that were of most interest to me.

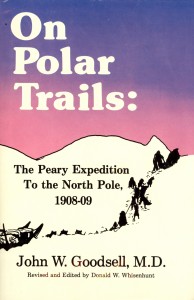

In 1981, the Mercer County Historical Society had published an edited version of On Polar Trails, which was an elaboration by Dr. Goodsell’s experiences with the Peary expedition, which he worked on actively until 1915 and revised several times long after that, at least into the mid-1930s. The book had never found a publisher in Goodsell’s lifetime. Unfortunately, Mercer County did not publish the book as Goodsell had written it.

One might ask, why Mercer County? Mercer County, Pennsylvania, lies east of Cleveland. Goodsell’s hometown was New Kensington, just east of greater Pittsburgh, but some distance south of Mercer County. The reason for it being the repository of many of Goodsell’s papers is because Dr. Goodsell lived out the last years of his life there, and his widow, who lived to 104, resided there in her old age. She eventually, in exchange for an “honorarium,” deposited what papers she had not previously donated elsewhere at the Mercer County Historical Society. As such, they do not represent a complete set of Goodsell’s personal papers, but they do contain many important items, including the original manuscript of “On Polar Trails,” and his original Peary expedition diary and the revisions he made of it, along with a considerable number of photographs taken by Goodsell on the expedition.

To bring Goodsell’s manuscript to publication, the society hired Donald W. Whisenhunt, a college professor at Wayne State University in Nebraska, who had earlier examined it and pronounced its publication “impossible.” Would that Whisenhunt’s initial opinion had been taken as the final word, because the way he eventually found to do the impossible proved he was a most unfortunate choice. In his introduction Whisenhunt detailed his methods.

Goodsell’s original typed manuscript was more than 600 pages. Whisenhunt judged this to be far too long and uninteresting “to today’s reader.” So he jettisoned Goodsell’s historical accounts of earlier polar expeditions and all of the scientific and technical material it included. He then rearranged what was left so that all the subject matter on various topics would appear together, losing the context in which Goodsell presented them. By this process, whole chapters were discarded, and in Whisenhunt’s own word, others were “emasculated.” The original 34 chapters were reduced to 12, and the 600+ typed pages became 178 small printed ones.

But even this was not enough for Whisenhunt. He then reviewed what remained for style and decided that Goodsell’s prose had to be modified because it was too “stilted, flowery, Victorian” and verging on the romantic and so would be “unfamiliar and probably of little interest,” and that his sentence structure was not up to “contemporary rules of good usage,” and so he rewrote them to be so.

“The reader may well conclude that the manuscript is no longer Goodsell’s,” Whisenhunt tellingly wrote. “That is a perfectly reasonable conclusion. Another editor may well have chosen to do the job much differently than I have. Someone else may have done it better and made it a better story. I would like to believe, however naively, that if Goodsell were alive and writing his story today he would have done it much as I have. I think it is important to note that the manuscript couldn’t not have been published without major revisions. For better or worse, I am the one who was chosen for the task.”

That’s small comfort, especially after such frank acknowledgment of the abuse of the original material. And Whisenhunt was wrong on almost all counts to take such liberties. What he produced from Goodsell’s finished book is a disservice to the scholarly community, if not “to today’s reader.” Worst, this being so, there is no way from Whisenhunt’s version to tell what is Goodsell’s and what is his in any given passage. Scholars want to see the words of eyewitnesses unvarnished by niceties such as “contemporary rules of good usage.” That’s the very point of primary source material: it is the authentic thoughts of the person who witnessed the events being described in his own words.

Having read Whisenhunt’s frank confession of gross tampering, I was very cautious in using anything quoted from On Polar Trails in writing my own book. What material I used from Goodsell came almost exclusively from the Peary papers, although, when I had no alternative, I quoted some crucial passages from the published book, while always cautioning my readers that they might not have been an accurate portrayal of Goodsell’s own words.

When Mercer County announced the publication of the so-called Dr. John Goodsell Archives, published under the title There and Back Again, in 2009, I contemplated purchasing a copy. It was massive—1,622 pages in two large volumes—so perhaps it justified the cost of $140 postpaid. Still, having had the experience of what they allowed Whisenhunt to do to On Polar Trails, I hesitated. Years passed, and of the thousands of libraries that make up OCLC’s union catalog WorldCat, only five libraries ever acquired a copy, so there was little possibility of loaning it.

Finally, I decided to just take the plunge. After all, “There and Back Again” had been Goodsell’s original title for his book about the Peary Expedition, so at least, I imagined, 600 of those 1,620 pages would be the original typed manuscript of it as Goodsell had written it, finally making amends for Whisenhunt’s misguided editing. The check was written and the books duly arrived. Included at no charge was the second massive disappointment foisted on the world of polar history scholarship by Mercer County Historical Society.

As for the first, on one of the preliminary pages was an advertisement offering leftover copies of On Polar Trails at $5 a copy, “while supplies last.” So much for Goodsell’s story as retold by Donald W. Whisenhunt having appeal “to today’s reader,” or those of the last 38 years for that matter!

In my next two blog posts I will give an analysis of what this publication contains, the good, the bad and the ugly, but—spoiler alert—for those with $140 to spare, I’d say save your money.

Filed in: Uncategorized.