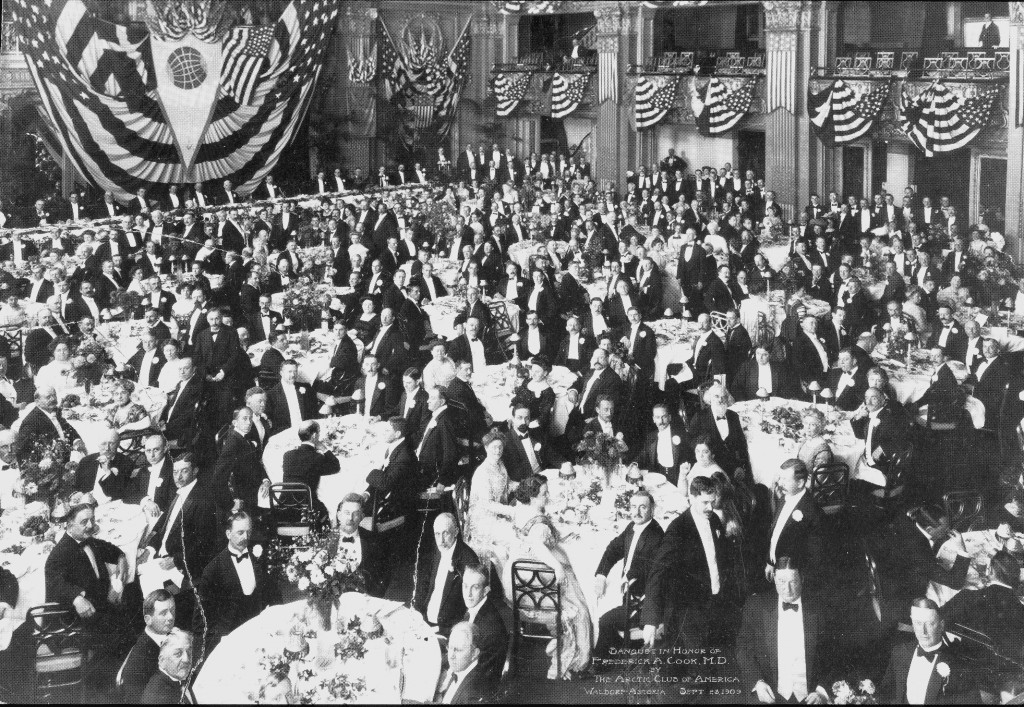

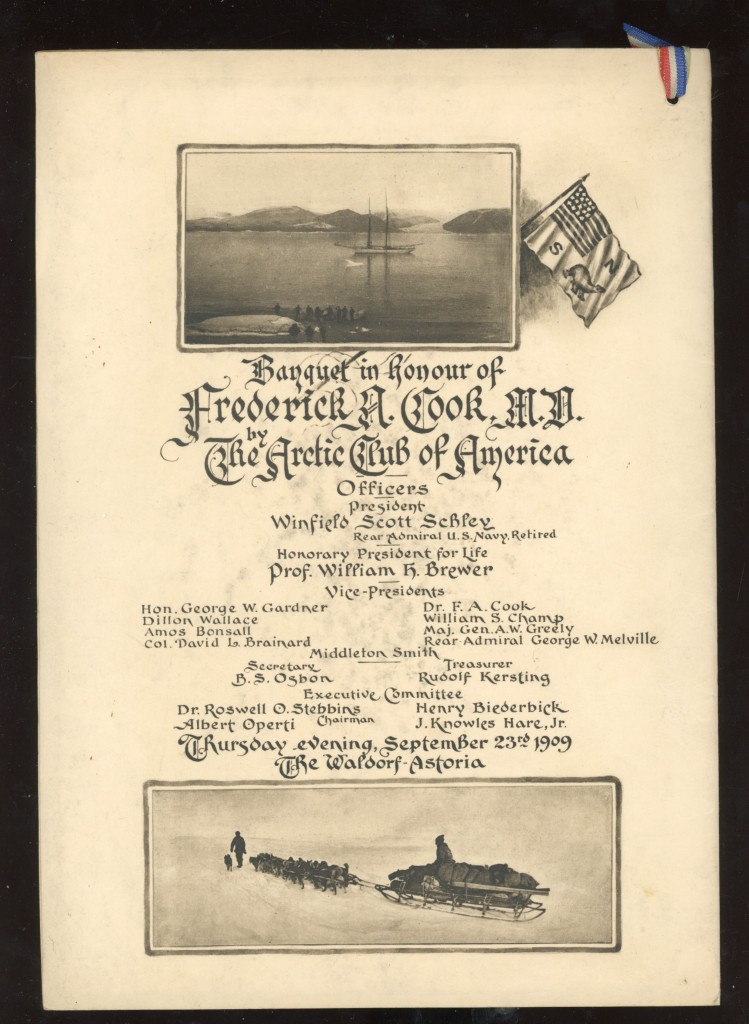

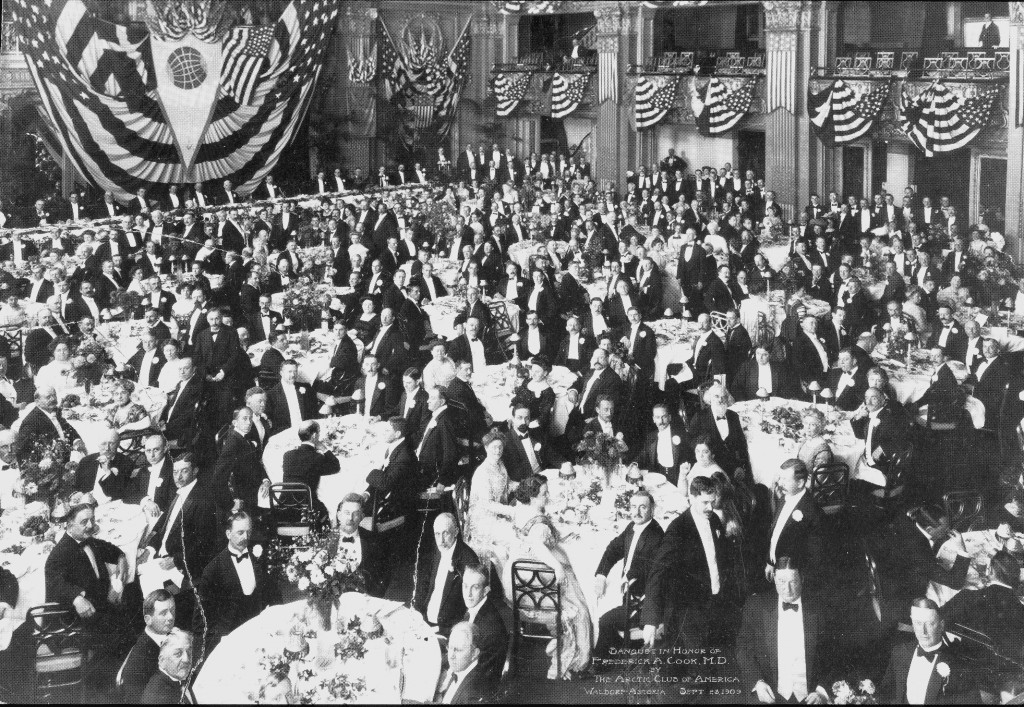

In the wake of his triumphal return to New York, and despite Peary’s charges that Cook’s prior claim to the North Pole was a “gold brick,” the Arctic Club of America decided on a gala dinner in his honor to be held on September 23 at the Waldorf-Astoria. A grand assembly of 1,185 guests in formal dress who had paid anywhere from $5-$30 for the privilege, thronged the vast banquet hall of the hotel, festooned with intertwined flags of the United States and Denmark. Cook, escorted by the club’s sitting president, retired Admiral Winfield Scott Schley, shook hands with more than 600 of them at the preliminary reception in the Astor Gallery before sitting down to dinner.

Over the head table hung the huge white burgee of the Bradley Arctic Expedition. In the official photograph of the event Dr. Cook is seated just to the left of the point of the burgee, with Admiral Schley to his left and John R. Bradley, the millionaire gambler who financed the expedition, to Cook’s right.

Over the head table hung the huge white burgee of the Bradley Arctic Expedition. In the official photograph of the event Dr. Cook is seated just to the left of the point of the burgee, with Admiral Schley to his left and John R. Bradley, the millionaire gambler who financed the expedition, to Cook’s right.

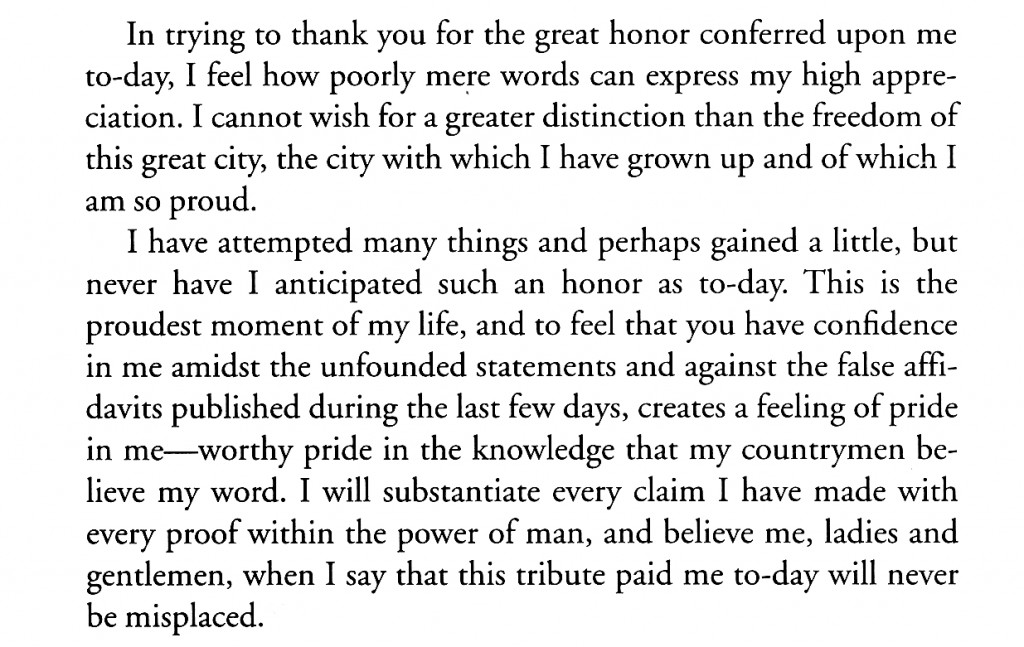

During the meal there were speeches and numberless toasts to the explorer’s health, including one from Count Harald Moltke, representing Denmark, where Cook had been received as a hero upon his return from the Arctic earlier in the month. It was 10 o’clock before Cook was introduced to speak by Admiral Schley to thunderous applause.

He thanked all those present, many who had been to the Arctic themselves, for “one of the highest honors I ever hope to receive,” and then, when he asked, referring to the growing controversy between him and Peary, “Now, gentlemen, I appeal to you as explorers and men. Am I bound to appeal to anybody, to any man, to any body of men, for a license to look for the pole?” he received a spontaneous and rousing “NO!” from the assembled dinners. When he paid homage to his benefactor, John R. Bradley was compelled to stand on his chair to acknowledge the ovation.

After his address, Cook adjourned to the Grand Ballroom, where he shook hands with more than 2,000 until midnight. At his departure he told Arctic Club officials, “My hand is a little sore but otherwise I never felt better in my life. It has been a great night and I hardly know how to express my appreciation for the cordial reception which has been given me by my fellow explorers. It is needless to say that the memory of this occasion will ever be cherished.”

Cherished, too, was the beautiful souvenir menu given each of the attendees. Here all of the pages are reproduced followed by a few comments on each of them.

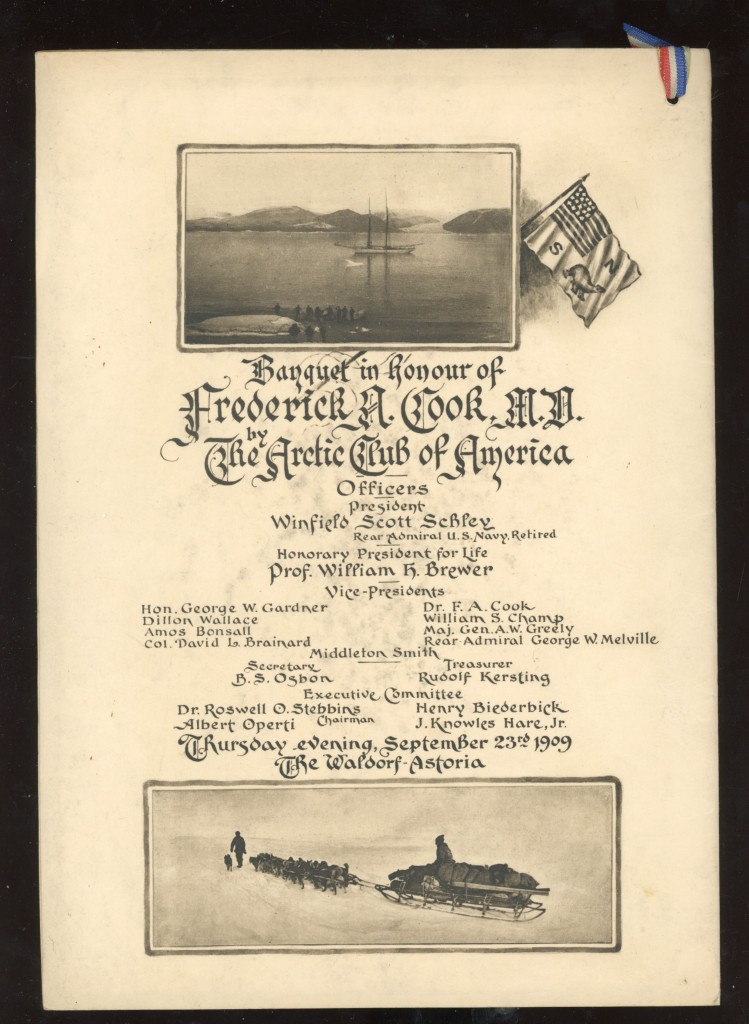

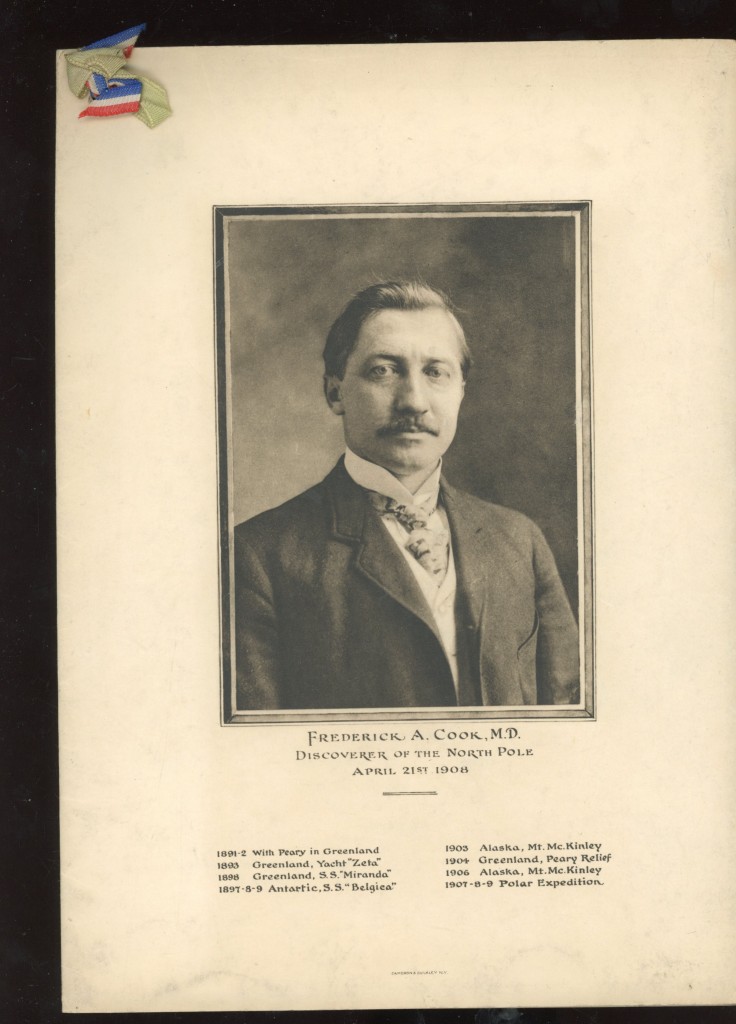

The menu consists of a fold-over cover forming its front and back, with seven one-sided pages bound in between at the upper left corner by a pair of ribbons, one white and the other red, white and blue.

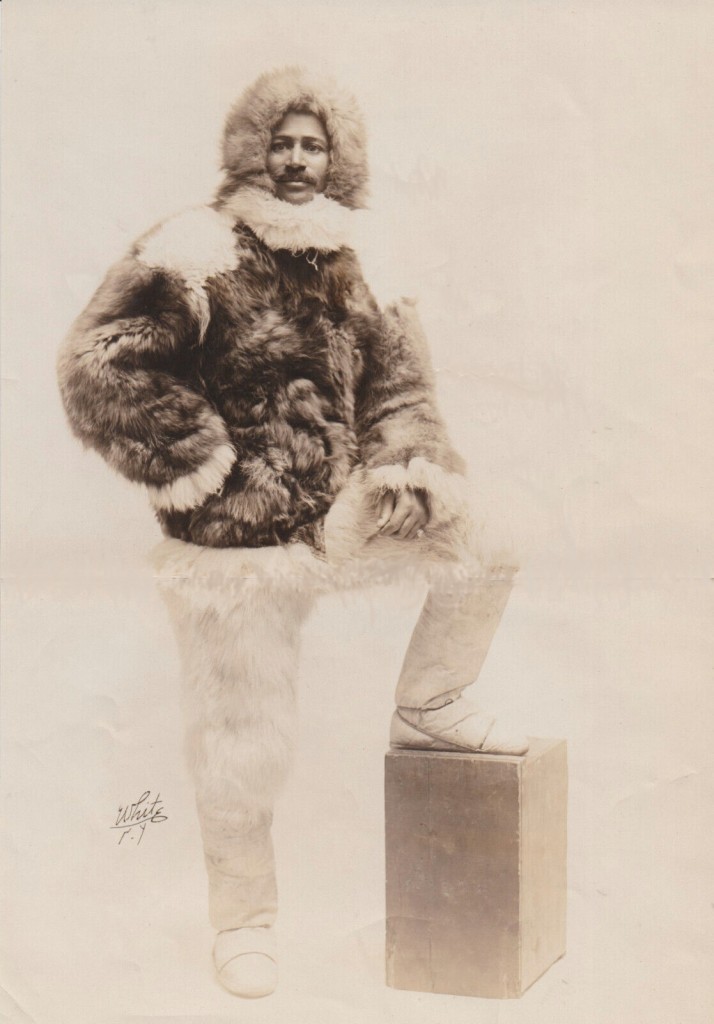

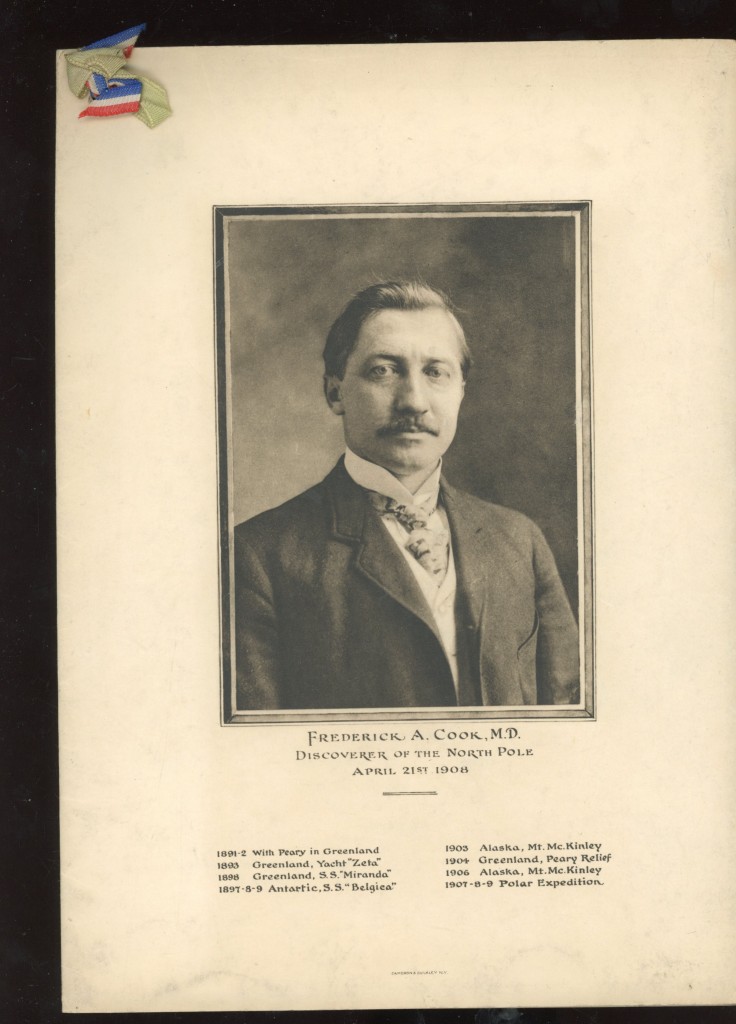

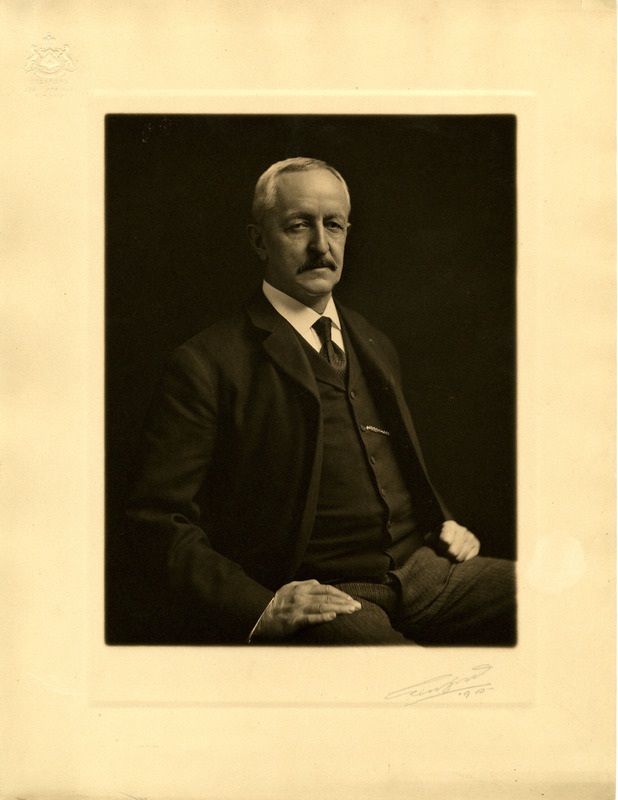

The front cover has a photogravure portrait of Cook taken in 1907. Below it is a list of the expeditions he participated in. The one listed as “1904” actually occurred in 1901, and so is out of order. This mistake is not repeated in Cook’s biography on page 3, where it is reported correctly.

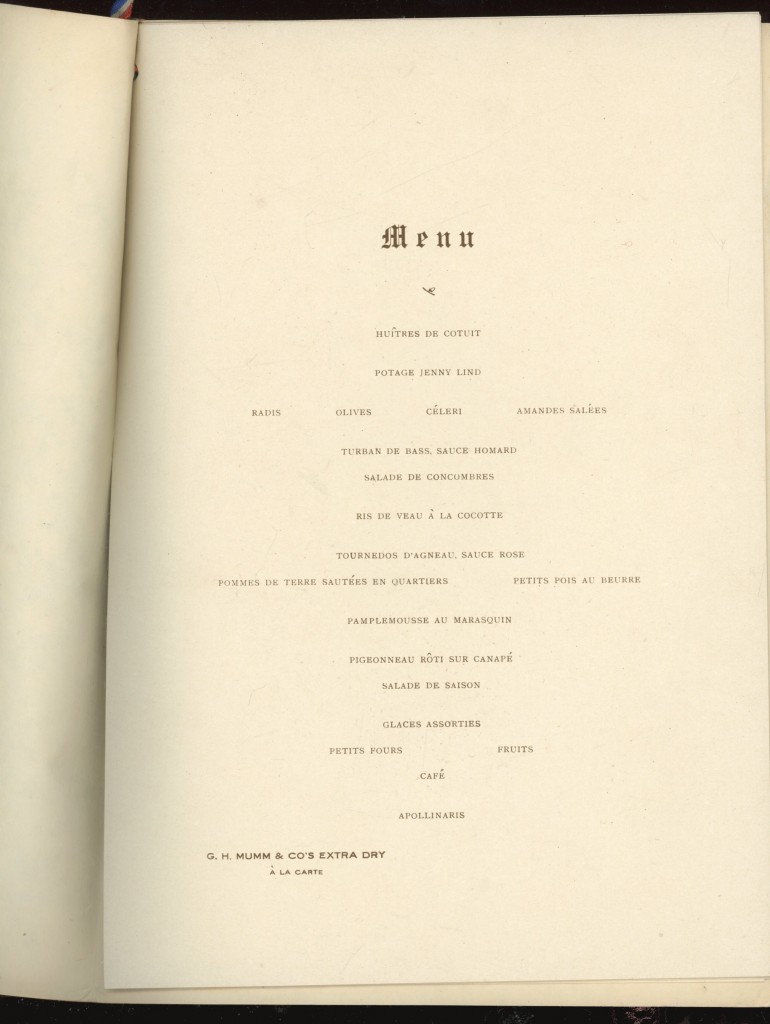

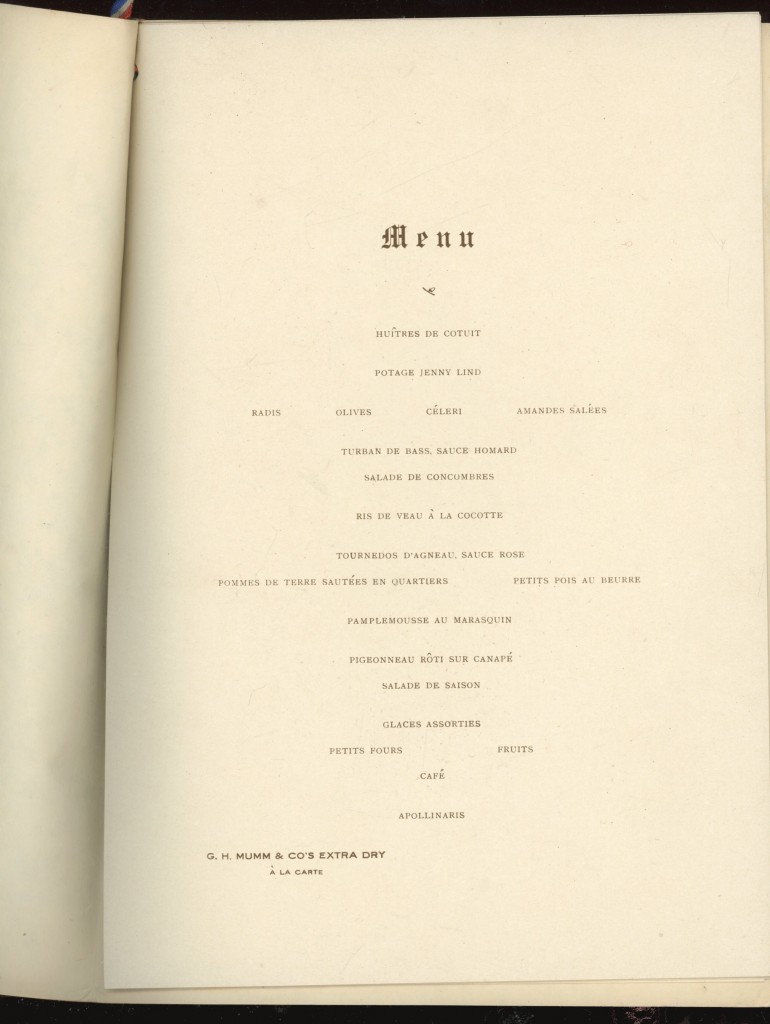

The first inner page presents the dinner menu, all in French. For those who don’t read French, the main course was roast squab.

The first inner page presents the dinner menu, all in French. For those who don’t read French, the main course was roast squab.

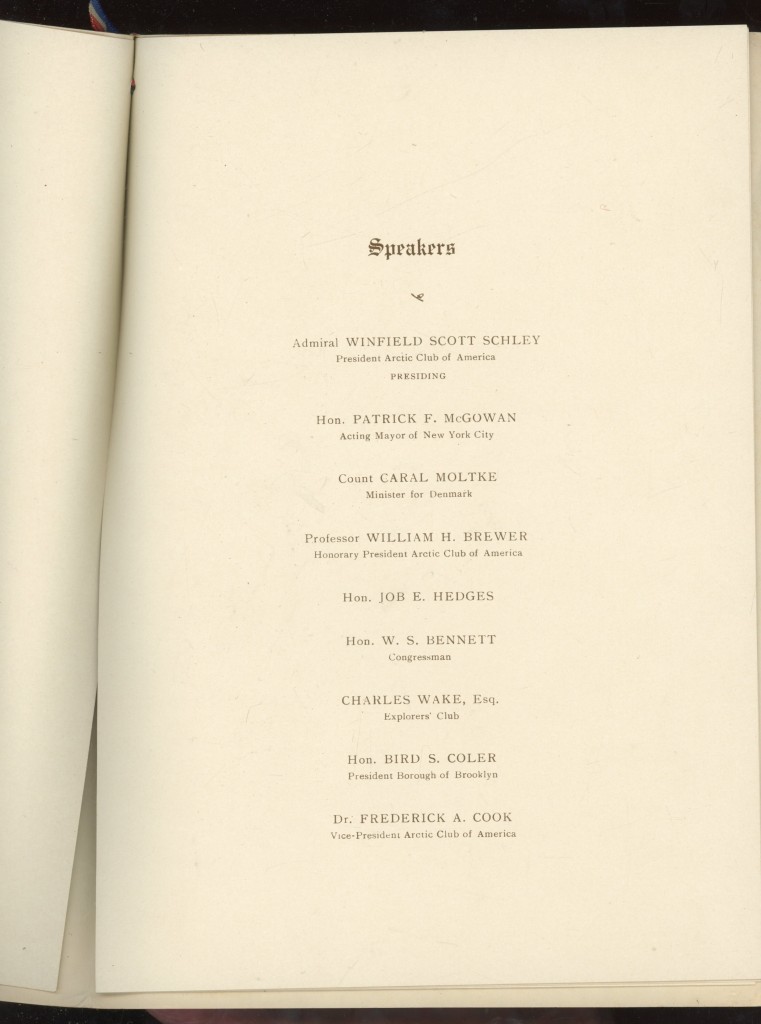

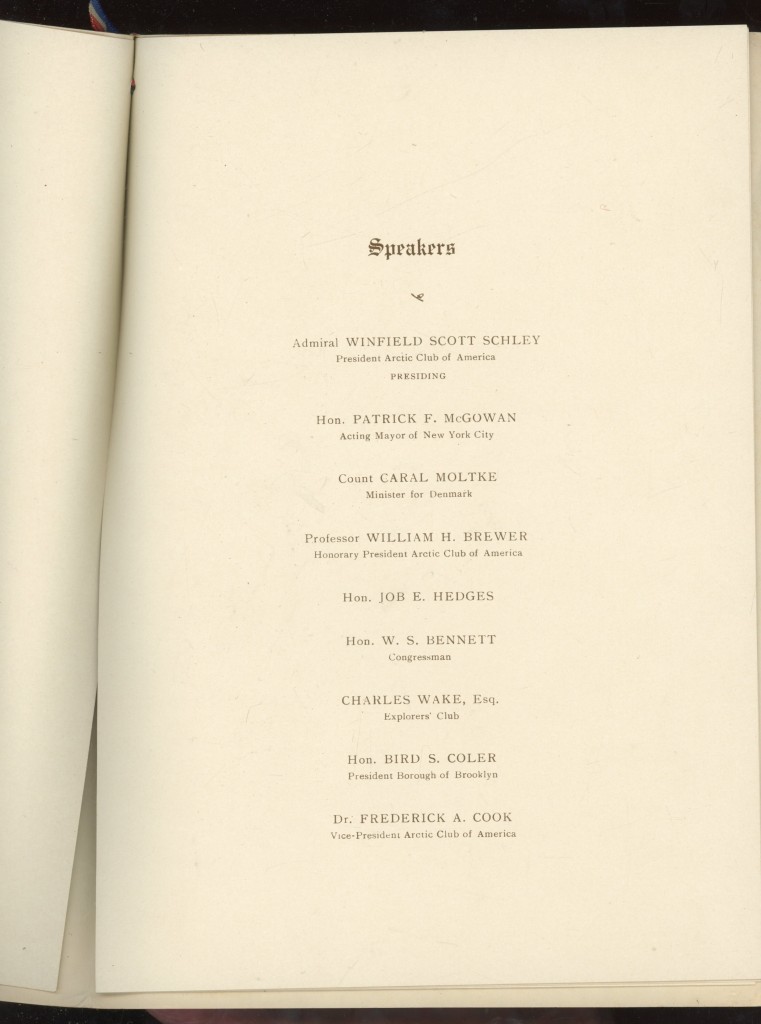

The second page lists the formal speakers. All are identified except for Job E. Hedges. He was an attorney and New York Republican political activist who would be the unsuccessful Republican nominee for Governor of New York in 1912. Dr. Cook was a Democrat.

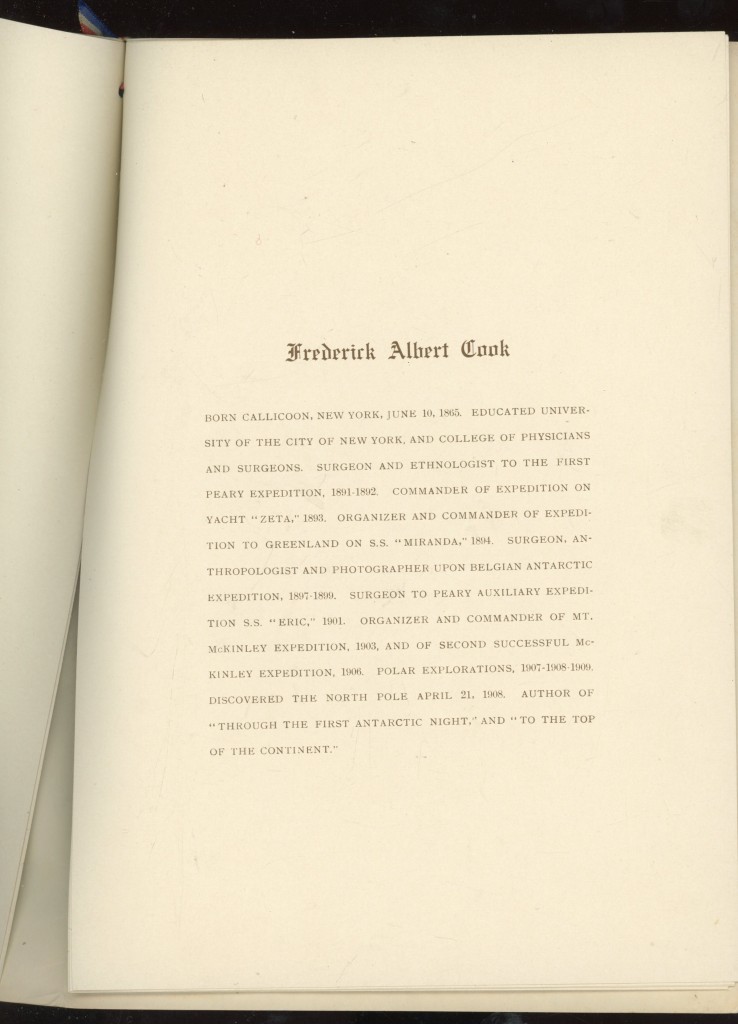

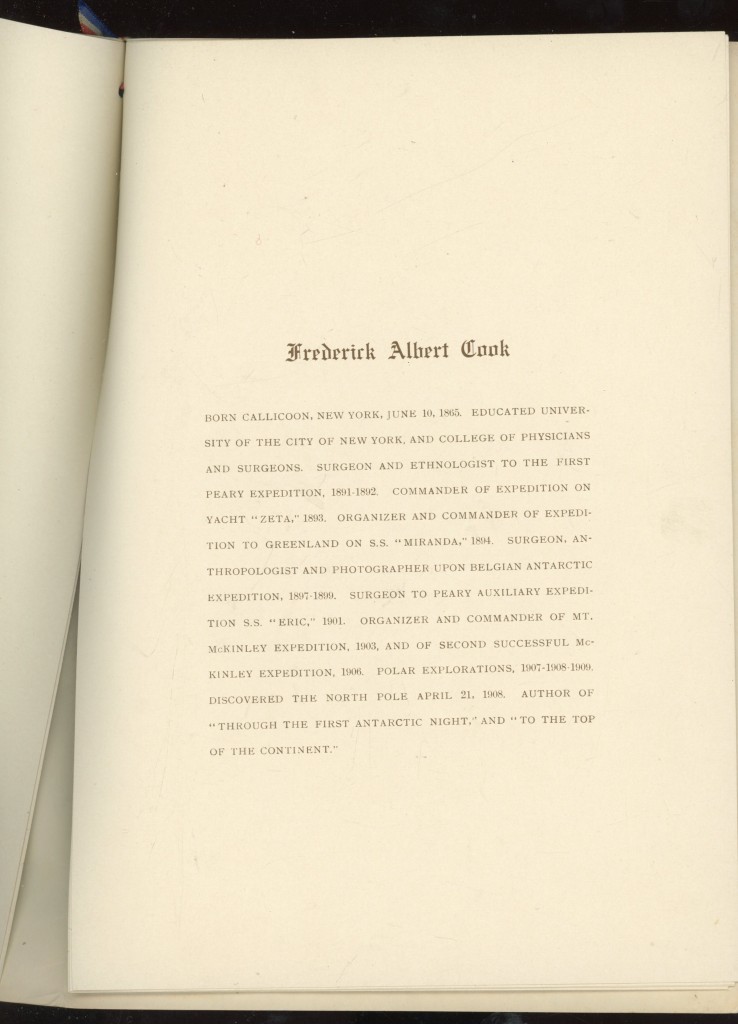

The third page, containing Cook’s biography, also has an error. Cook was not born in Callicoon, New York, but in Hortonville, a hamlet a few miles north of that town.

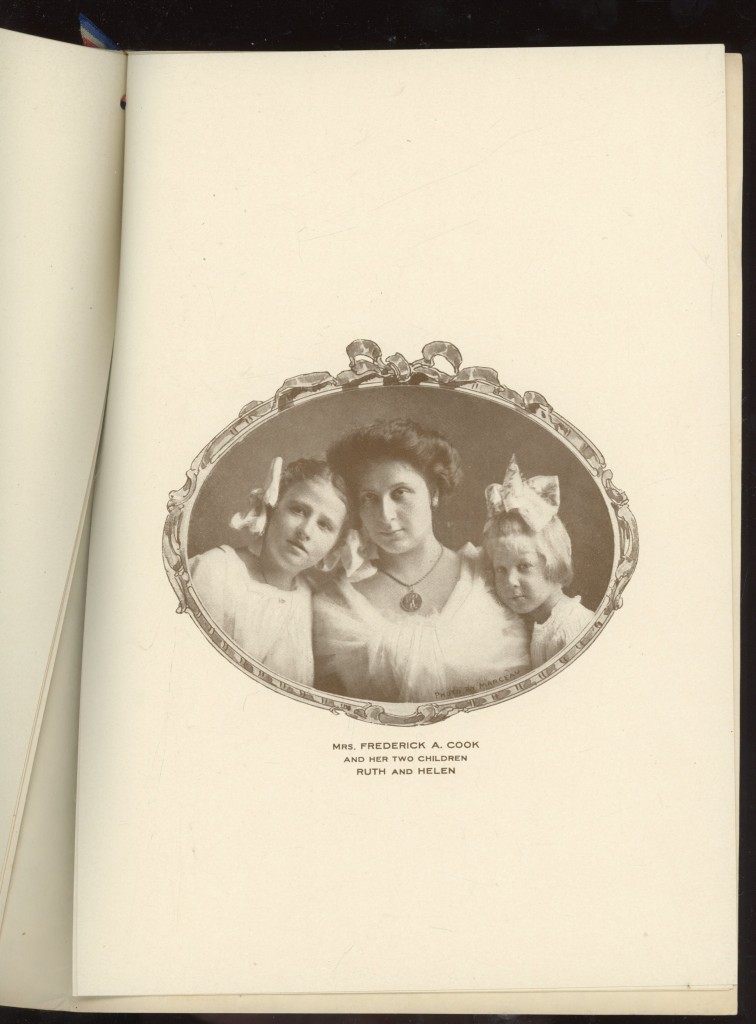

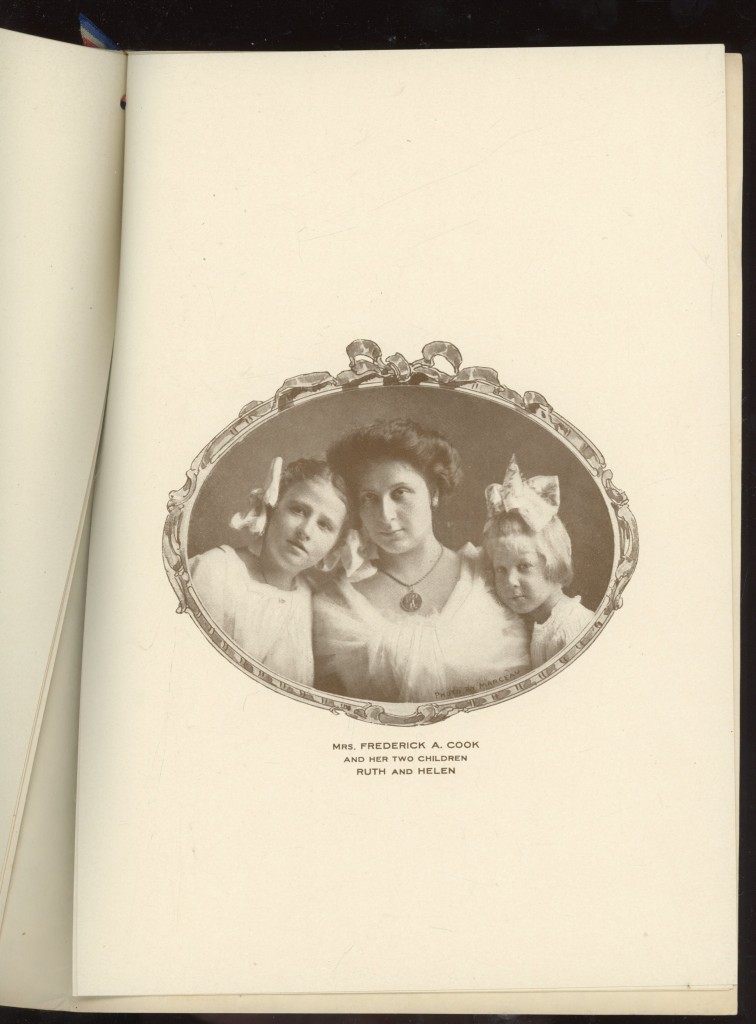

The fourth page portrait of Dr. Cook’s wife, Marie Fidell Hunt, shows her wearing on a chain around her neck one of the silver medals Cook received from the city of Brussels in appreciation of his service as surgeon to the Belgian Antarctic Expedition. At the time she married Cook in 1902, Marie was the widow of Dr. Willis Hunt of Camden, NJ. Ruth Hunt (left) was her daughter by that first marriage, born in 1898. Helen, who was Dr. Cook’s only surviving natural child, was born in 1905. She was named after Helen Bridgman, wife of Herbert L. Bridgman, longtime Secretary of the Peary Arctic Club. Perhaps that is why she styled herself Helene in adulthood. The white silk gown Marie Cook wore to the dinner is preserved at the Sullivan County Historical Society in Hurleyville, NY.

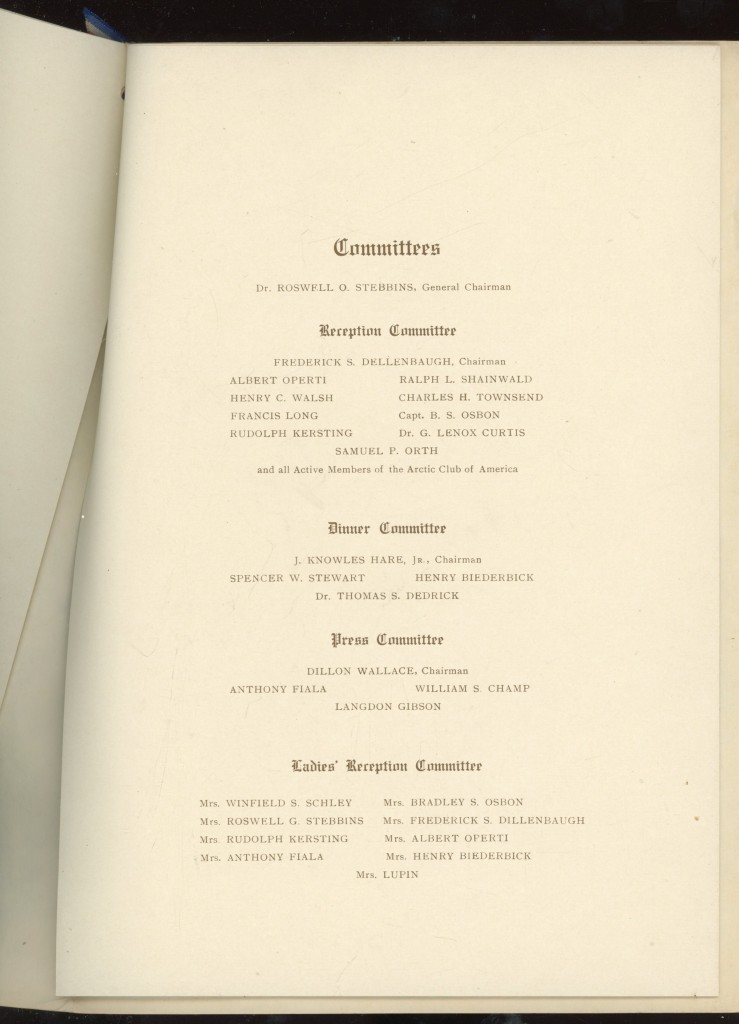

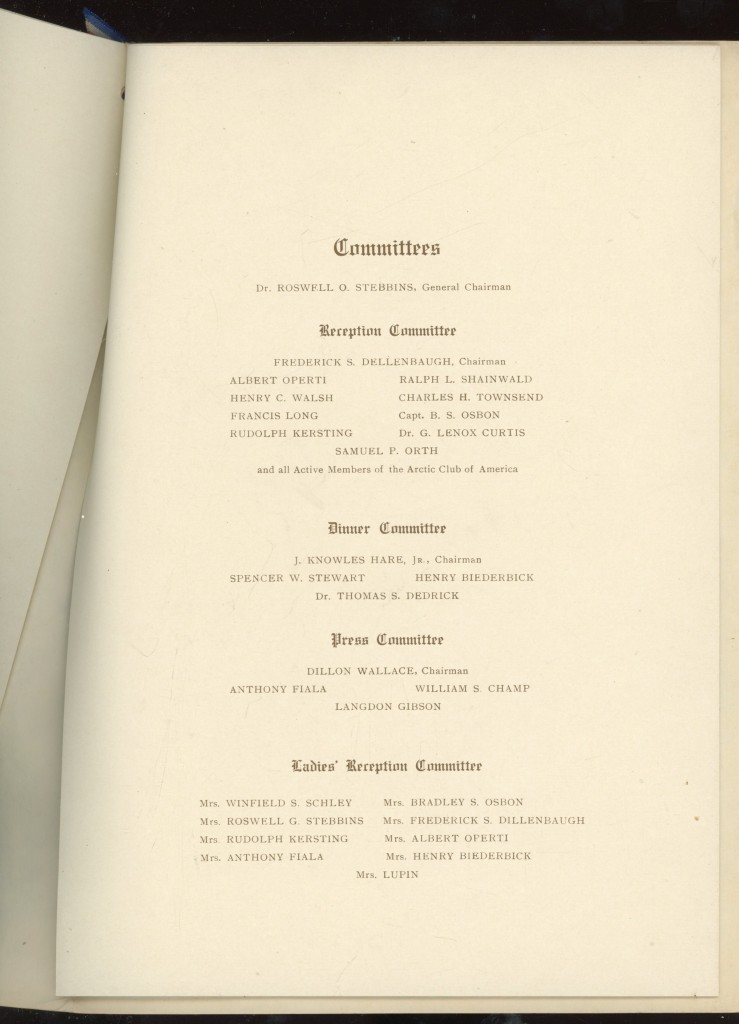

The fifth page shows the committees responsible for the event. The Arctic Club was formed in 1894 by the “survivors” of the disastrous Miranda expedition organized by Cook that year. The ship was lost but there were no casualties. Many of its later members were members of various arctic expeditions. The Arctic Club was absorbed by the Explorers Club in 1913. Cook was the second president of both clubs.

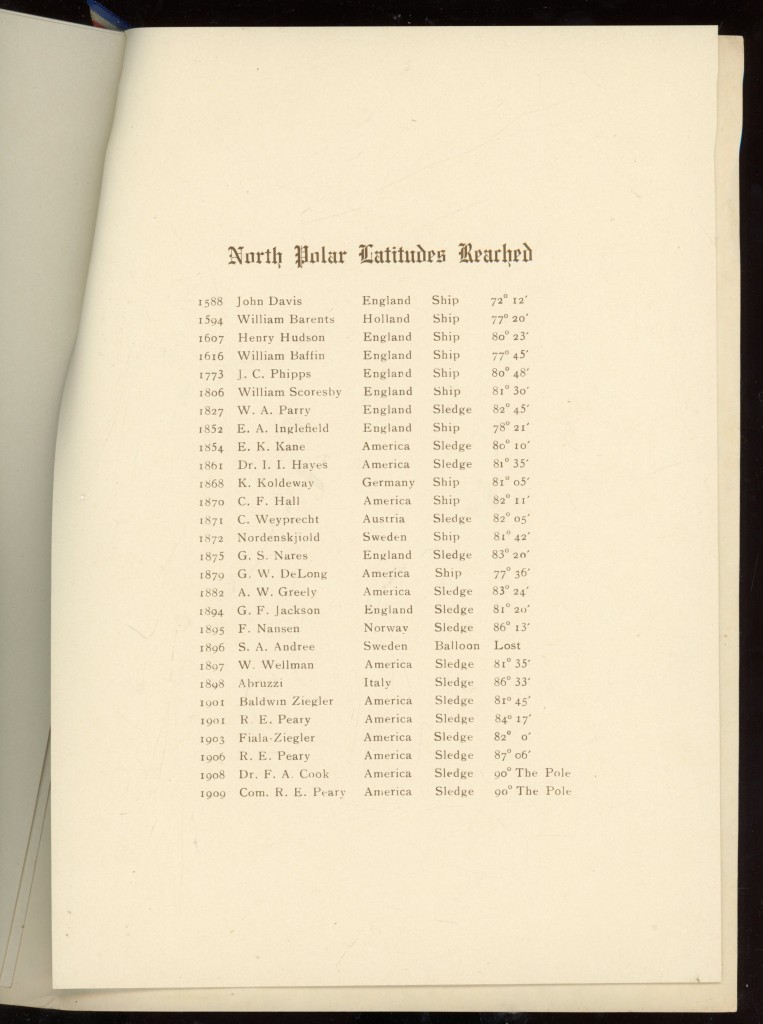

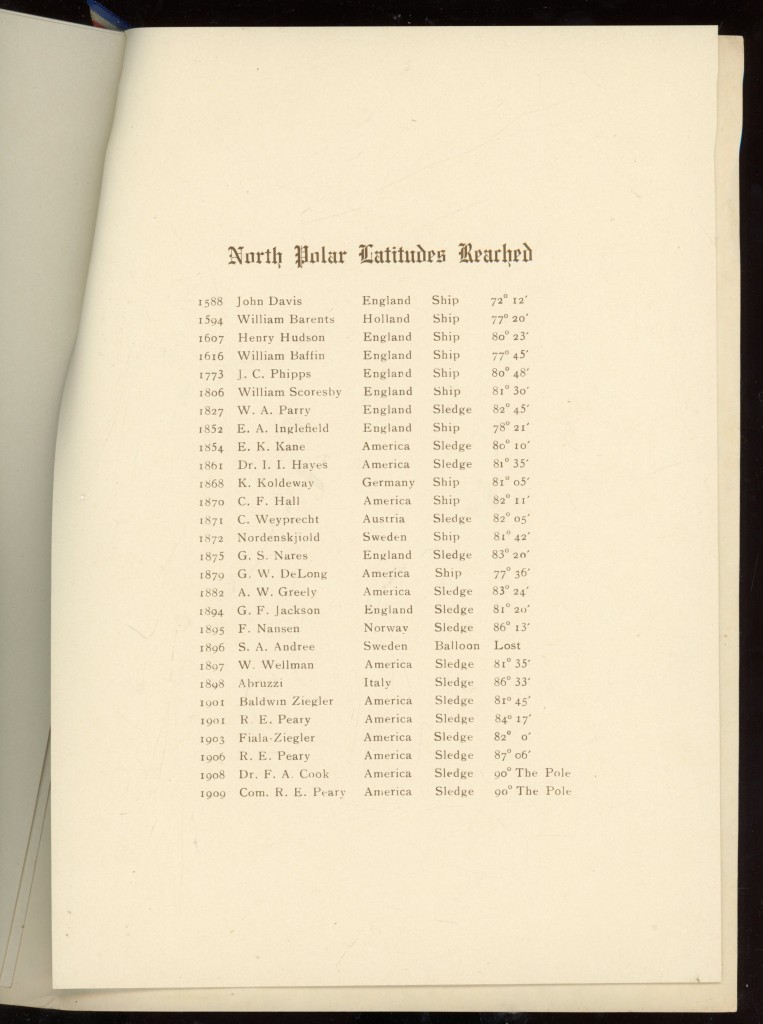

The sixth page shows a list of “farthest norths” reached by various explorers.

The back cover shows the yacht John R. Bradley in Foulke Fjord, the harbor at Etah, Greenland, flanked by the Arctic Club’s flag. This was the ship that took Cook to the Arctic in 1907 for his attempt on the Pole the following Spring. This is followed by a list of the officers of the club. Professor Brewer was the first president and honorary President for Life thereafter. His papers are held at Yale University. Below the officers list is a photograph taken on the 1903 Fiala-Ziegler Expedition by Anthony Fiala on his failed attempt to reach the North Pole in 1904. The sled shown in it was built by Dr. Cook’s brother, Theodore.

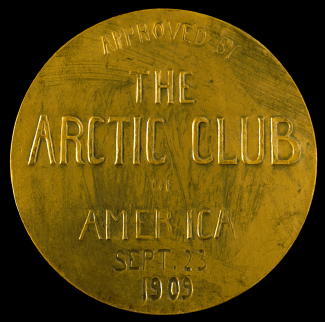

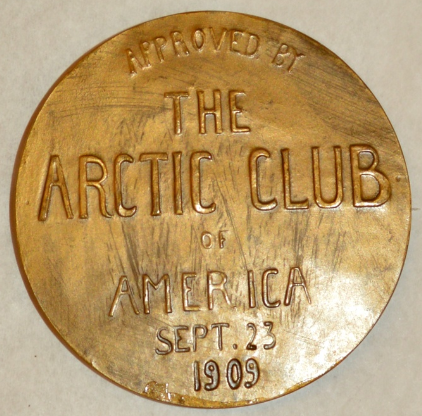

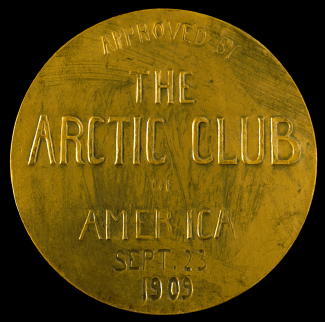

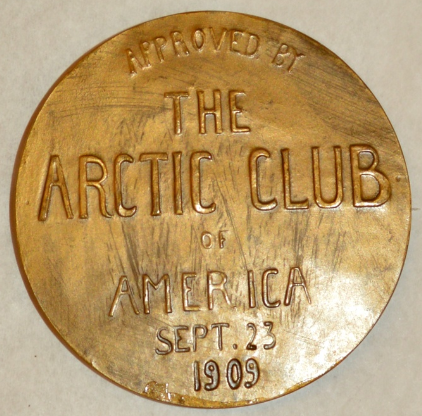

The Arctic Club authorized the striking of a gold medal to be presented to Cook at the banquet. For many years the whereabouts of this medal were not known. About 2005 it was disclosed to be in the collections of the Missouri Historical Society of St. Louis. It was donated to the society in 1914 by an unrecorded benefactor.

Here is its official description from the society’s website:

“Commemorative Polar Exploration Medal Presented to Dr. Frederick A. Cook

The Arctic Club of America honored Dr. Frederick A. Cook by presenting this medal to him at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York, September 23, 1909. Cook claimed to have discovered the North Pole just days before Admiral Robert E. Peary announced he had also reached the pole. When Cook failed to prove that he had beaten Peary, the Arctic Club of America revoked his membership.”

The item identifier is 1914-029-0001 and can be viewed at:

https://mohistory.org/collections/item/1914-029-0001

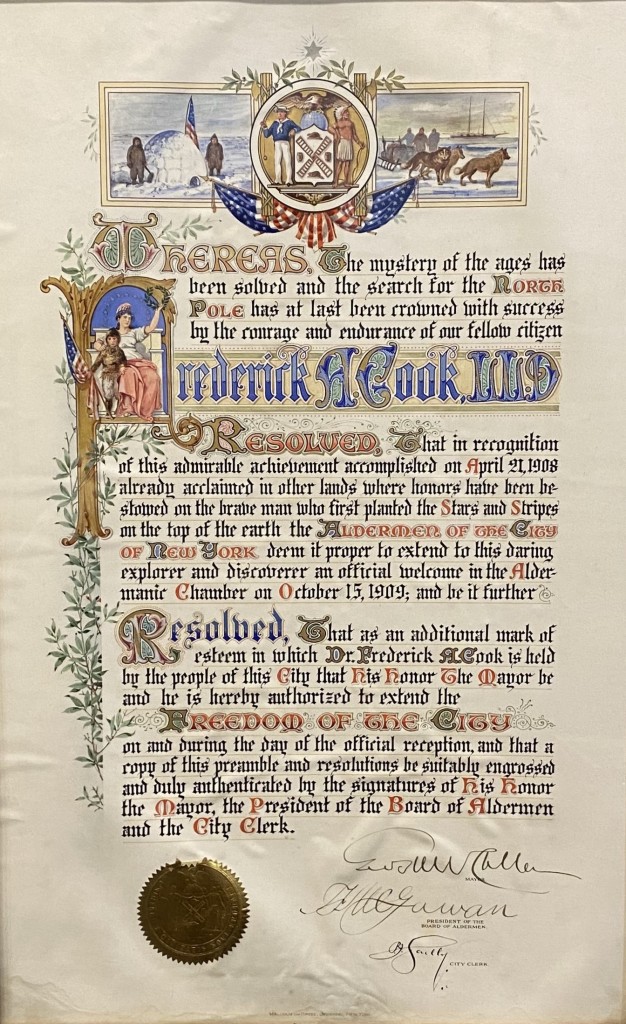

This description is not quite correct. The medal was was not ready in time for the Arctic Club dinner. On October 15 Cook was scheduled to receive the unprecedented honor for an American citizen of the Freedom of the City of New York at the Aldermans’ Chamber in City Hall. Before he received the illuminated vellum scroll signifying this honor, he was presented with the Arctic Club’s gold medal by Dr. Roswell Stebbins, a doctor of dentistry, as its representative. In handing it to Cook the medal dropped to the floor, rolled away and had to be chased down.

Cook’s membership in the Arctic Club was not “revoked” when he failed to prove his claim. The official reason given for dropping him from its rolls was for “non-payment of dues.”

The medal is 2 ½ inches in diameter. On the obverse Cook is shown, standing within the rings of latitude culminating in the North Pole, holding an American flag. Around the edges can be seen the lands bordering on the Arctic Ocean. It bears the inscriptions “April 21, 1908,” the date Cook claimed to have been at the Pole, and within that “F.A. Cook.” A copyright notice and the artist’s name are in incurse letters at the bottom edge.

The reverse bears the inscription: “APPROVED BY / THE / ARCTIC CLUB / OF / AMERICA / SEPT. 23 / 1909.”, the date being engraved in incurse letters after the medal was struck.

The photo of the banquet is in the photographic collections of the Library of Congress.

The photos of the menu are all courtesy of Keith Thompson.

The photos of the medal are courtesy of the Missouri Historical Society of St. Louis, MO.

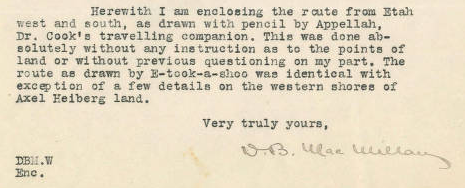

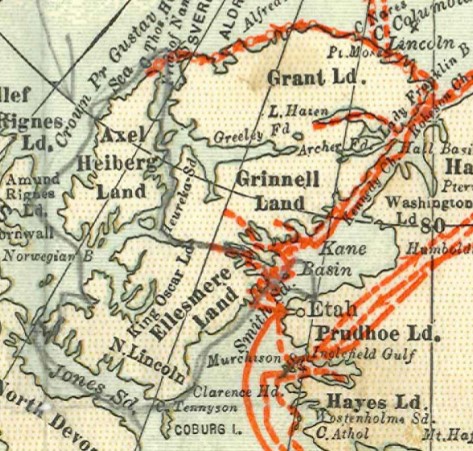

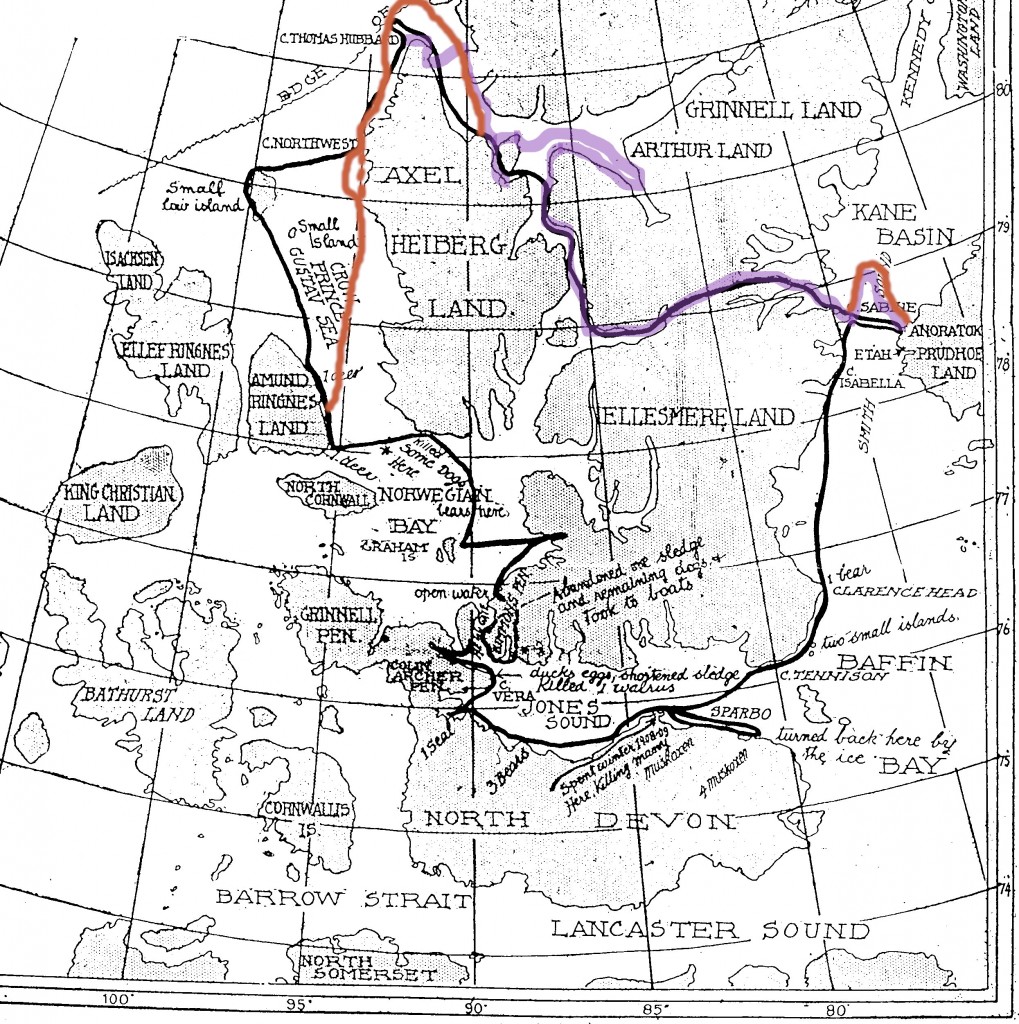

Etukishook’s route is show on the map in black. Dr. Cook’s actual route up to the time he reached Cape Thomas Hubbard, as indicated in his original 1908 notebook kept on his polar attempt, is shown on this map in purple. Ahwelah’s route, where it differs from the Peary map’s route has been indicated in orange. A comparison of the three routes brings up some interesting points.

Etukishook’s route is show on the map in black. Dr. Cook’s actual route up to the time he reached Cape Thomas Hubbard, as indicated in his original 1908 notebook kept on his polar attempt, is shown on this map in purple. Ahwelah’s route, where it differs from the Peary map’s route has been indicated in orange. A comparison of the three routes brings up some interesting points.

Over the head table hung the huge white burgee of the Bradley Arctic Expedition. In the official photograph of the event Dr. Cook is seated just to the left of the point of the burgee, with Admiral Schley to his left and John R. Bradley, the millionaire gambler who financed the expedition, to Cook’s right.

Over the head table hung the huge white burgee of the Bradley Arctic Expedition. In the official photograph of the event Dr. Cook is seated just to the left of the point of the burgee, with Admiral Schley to his left and John R. Bradley, the millionaire gambler who financed the expedition, to Cook’s right.

The first inner page presents the dinner menu, all in French. For those who don’t read French, the main course was roast squab.

The first inner page presents the dinner menu, all in French. For those who don’t read French, the main course was roast squab.