Dr. Cook Artifacts 2: The Esquimaux pitchers

Written on November 10, 2021

In the summer of 1893, after his return from Greenland where he had been surgeon to Peary’s North Greenland Expedition, Frederick Cook was hired to be “guide” for a tour of Greenland aboard the yacht Zeta. The ship had been chartered by a Yale professor on behalf of his half-addled son, who had developed an uncontrollable obsession with the notion of seeing the Far North after hearing Peary speak of his experiences there at one of his lectures the previous winter. It was on this voyage that Cook first conceived of an American Antarctic Expedition with himself as its leader. To that end he traded for fur garments and dogs while in the Danish settlements. But how to finance it?

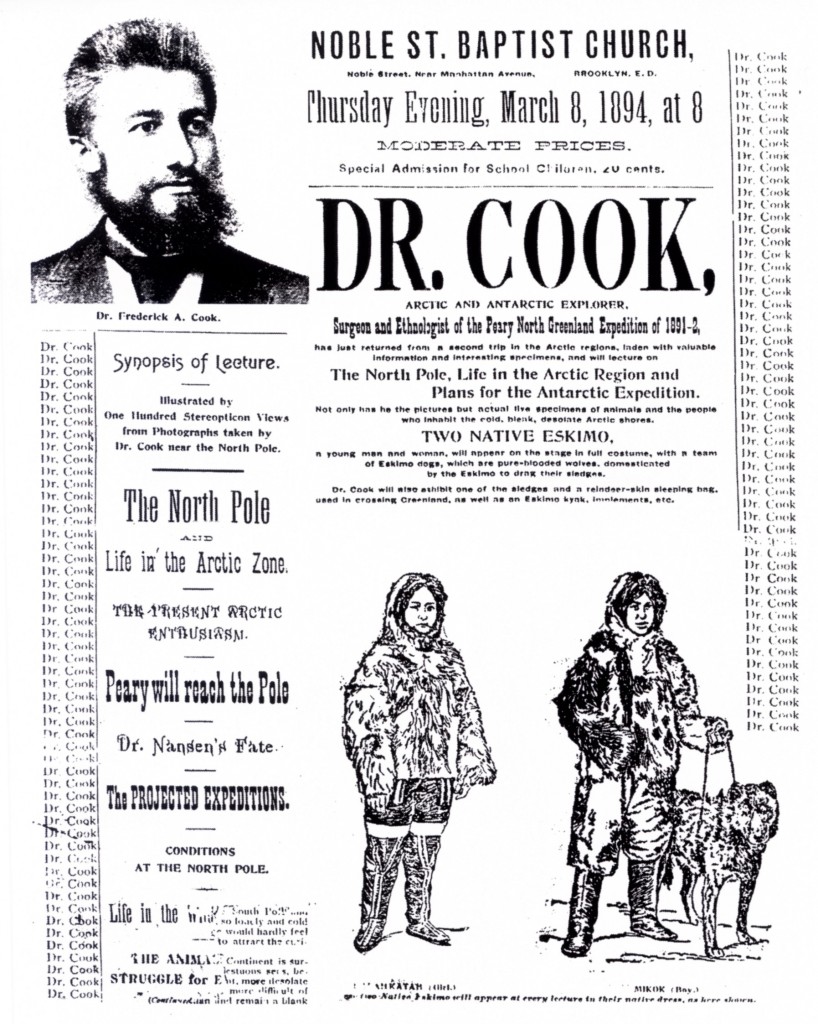

When the Zeta touched at Rigolet, Labrador, he met an Inuit man who worked for the Hudson’s Bay Co. who had two teenage children. Before the Zeta sailed Cook somehow persuaded the man to allow him to take the two, a 16-year old girl named Kahlahkatak, and a 14-year old boy named Mekok, back with him to the United States, promising to return them the following year. For convenience, Cook renamed his wards Clara and Willie.

Once back in Brooklyn he put the two children up at his brother’s house on Bedford Avenue. It wasn’t long before the New York newspapers carried amusing accounts of the first “full-blooded Eskimos” ever to visit America. The children were amazed by the tall buildings and feared the heights of the bridges. They detested ice cream, and complained about the weather being too cold. All the time, Dr. Cook continued to plan his assault on the nearly-unknown Antarctic continent.

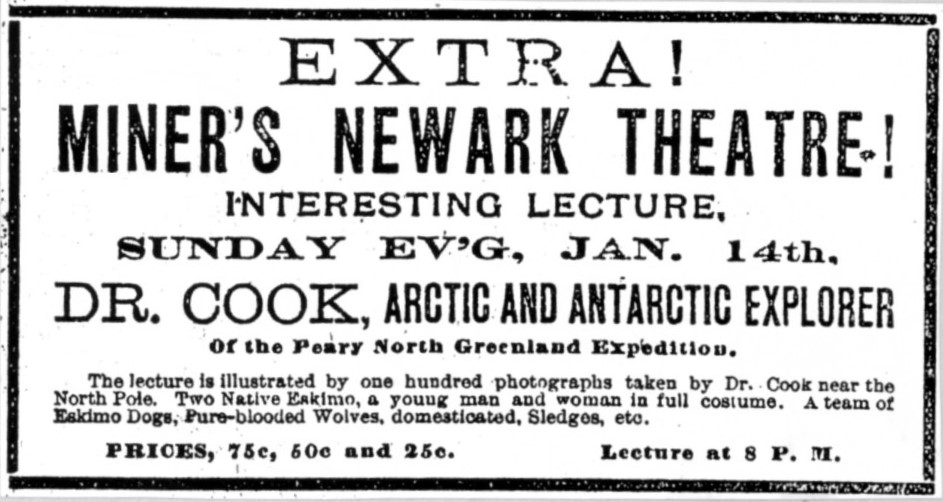

He petitioned the American Geographical Society for financial support, and when that was not forthcoming, he contracted with the famous impresario of the lecture platform, Major James B. Pond, for a series of lectures on his experiences in the Arctic and the curious culture of it’s inhabitants.

Throughout the winter Cook toured New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Connecticut and Massachusetts, at admission prices ranging from 25 to 75 cents, illustrating his lecture with a hundred stereo-opticon views of Greenland. At his appearances he exhibited some of his dogs and also Willie and Clara, got up as if they were “wild people” in fur costumes he had obtained in Greenland. He never mentioned that instead of an igloo, the two children lived with their parents in a civilized log house in Rigolet, but implied instead that they lived in the traditional Inuit style.

After the tour ended, Cook continued to exhibit at Huber’s Dime Museum at $300 a week, where he appeared nine times a day on a stage set up to look like and Inuit encampment. He populated this “village” with not only Willie and Clara, but also four of the ten Labrador Inuit who had been abandoned by their exhibitors after the close of the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago the previous fall. His initial run of appearances at Huber’s was a big success, and the owner wanted him to continue longer, but Cook cut them short when one of the World’s Fair Inuit took sick and died.

To supplement his income from his appearances, Cook had made up a large number of stoneware milk pitchers trimmed in gold and bearing a colored transfer image of either Mekok with a native dog, or Kahlahkatak holding a puppy, based on photographs he had used in his promotional literature for his lectures. These he sold as souvenirs, probably for 25 cents each. Judging by the proportions they turn up today, it appears that Kahlahkatak’s pitcher was the better seller. It seems about three times more common than Mekok’s pitcher.

To supplement his income from his appearances, Cook had made up a large number of stoneware milk pitchers trimmed in gold and bearing a colored transfer image of either Mekok with a native dog, or Kahlahkatak holding a puppy, based on photographs he had used in his promotional literature for his lectures. These he sold as souvenirs, probably for 25 cents each. Judging by the proportions they turn up today, it appears that Kahlahkatak’s pitcher was the better seller. It seems about three times more common than Mekok’s pitcher.

Cook also was accompanied by Clara and Willie at lectures he gave to the New York Obstetrical Association and the Brooklyn Gynecological Society, at which he first described the hitherto unrecognized details surrounding the spacing of Inuit births and the seasonality of the menstrual cycle in Inuit women. As a result of these lectures, Cook was elected a member of the American Ethnological Association. He also took the children along when he entered some of his wolfish dogs into the Westchester Kennel Club show in 1894, winning three prizes there.

None of this produced either the kind of money or the backing he needed to attack the Antarctic fastness, however. So Cook hatched the idea of a “tourist jaunt” to Greenland in the summer of 1894 aboard the steamer Miranda for well-healed excursionists at $500 a head (about a $3,500 today), with famously disastrous consequences. The ship hit an iceberg, ran into a reef and foundered on the way home, but all the passengers were saved.

On the way out on that ill-fated voyage, Cook stopped again at Rigolet to return not only Willie and Clara, but also the nine surviving World’s Fair Inuit, who came from the same region of Labrador.

Today, these sturdy stoneware pitchers remain as lasting reminders of this little known early phase of Dr. Cook’s eventful career.

Filed in: Uncategorized.