Dr. Cook Artifacts 3: Welcome Home, Dr. Cook, September 21, 1909

Written on December 9, 2021

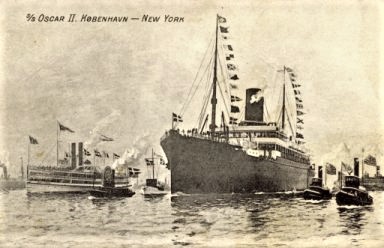

Dr. Cook returned to America aboard S. S. Oscar II after a week of adulation in Denmark. At half-past midnight the ship proceeded to quarantine, arriving at 4 AM. There she was dressed in flags to meet the reception committee aboard The Grand Republic, chartered by the secretary of the Arctic Club, B.S. Osbon. During the night a number of boats bearing newspaper men tried to board the ocean liner, but were unsuccessful. The best they could do was shouting questions at Dr. Cook who was standing at the gangway as he awaited the arrival of his wife, Marie, and children, Ruth and Helen, aboard the tug John K. Gilkinson.

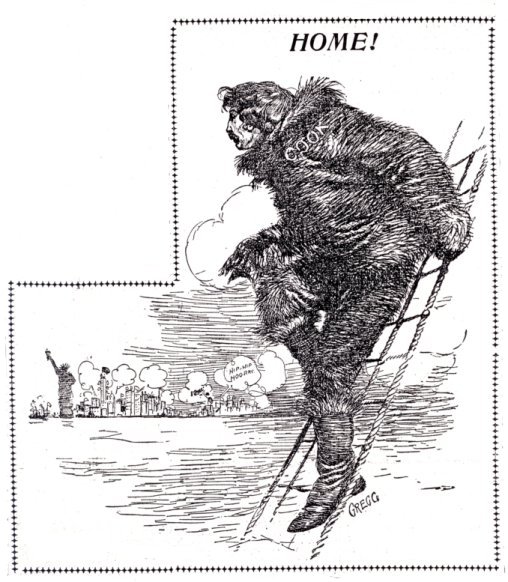

At dawn, as the tug approached, the Gilkinson was accompanied by a number of boats including the New York Herald’s dispatch boat Owlet. The Herald was then running a serial of Dr. Cook’s narrative of his expedition. As the tug came along side, Cook descended the rope ladder and leapt to its deck. For half an hour the tug lay dead in the water while Dr. Cook visited with his family in the cabin, while the passengers on the Oscar II broke out into a chorus of “For he’s a jolly good fellow.”

The Grand Republic soon appeared, and at 9 AM Dr. Cook and his party transferred to the steamer, which was visibly listing to one side from the weight of its 424 passengers lining the deck rail.

In this postcard view, left to right are: The Grand Republic, John K. Gilkinson, Owlet, and Oscar II.

It was planned that the doctor would pass through an honor guard of the 47th Regiment, where he was supposed to be met with a wreath of white tea roses, to be placed ceremoniously around his neck by Miss Ida A. Lehmann of Brooklyn, daughter of the secretary of the Dr. Cook Celebration Committee of 100. As it was, the honor guard in their white and blue dress uniforms were too busy trying to help Captain Osbon keep the guest of honor from being crushed to death to perform their designated function, and Miss Lehmann barely managed to lasso the doctor with the wreath, which itself was soon crushed to lifelessness as he was buffet around on the deck by the happy crowd.

Cook managed to take refuge on the hurricane deck, from which he gave a short speech that was all but inaudible over the shrieking whistles of all the ships in the harbor that had been assembled for a naval parade as part of the Hudson-Fulton Celebration.

It was now 9:30, and the reception was not set until noon, so to kill time The Grand Republic cruised slowly up the North River as far a Spuyten Duyvil, then docked briefly at 130th street to let off some of its passengers before passing back down the river. After one more turn, she docked at Williamsburg’s South Fifth Street wharves below the sugar refineries to a tremendous cheer from the thousands waiting on shore, accompanied by a great blast of whistles from the factories and the ships on the river.

With the assistance of 100 police officers, Cook’s party struggled through an estimated crowd of 5,000 on the wharf to enter a car to start a parade, led by a flatbed truck with a brass band, to start along the five-mile route to the Bushwick Club, where the official reception was to be given.

Left to right: Bird Coler (with hat in hand), Brooklyn Borough President, B.S. Osbon, Ruth Cook, Dr. Cook, Mrs. Cook; William Cook, his brother, stands behind the policeman.

Along the parade route stood 100,000 people. It seemed everyone in the whole borough was in the streets, and as he passed along, Cook acknowledged their plaudits by raising his hat, smiling and bowing.

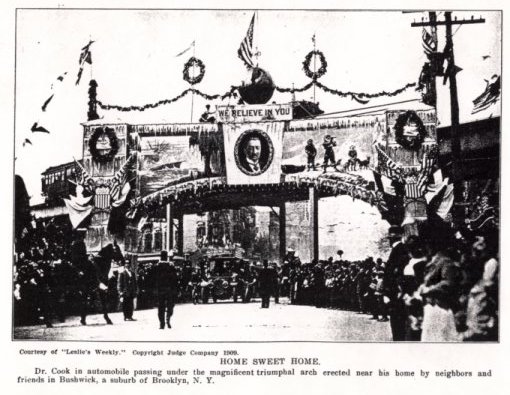

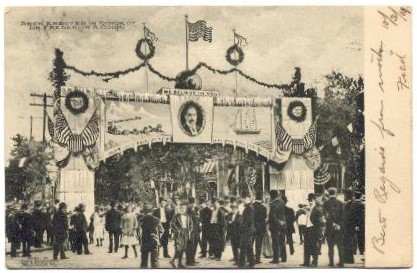

As the procession turned the corner directly opposite his old home on Bushwick Ave., the doctor caught sight of the triumphal arch erected by his neighborhood association over the intersection of Myrtle and Willoughby. It was a huge canvas and wood frame structure as high as the El viaduct next to it. Surmounted with laurel wreaths and garlands, it bore a giant golden globe with a flag flying from its top. It dripped with painted icicles and electric lights and was decorated with arctic scenes, shields, more flags, and a portrait of Cook crowned with the words “We Believe in You.” Four snow white pigeons were released as the doctor’s car passed under the archway by a man atop the arch. (both sides of the arch are shown here)

As the procession turned the corner directly opposite his old home on Bushwick Ave., the doctor caught sight of the triumphal arch erected by his neighborhood association over the intersection of Myrtle and Willoughby. It was a huge canvas and wood frame structure as high as the El viaduct next to it. Surmounted with laurel wreaths and garlands, it bore a giant golden globe with a flag flying from its top. It dripped with painted icicles and electric lights and was decorated with arctic scenes, shields, more flags, and a portrait of Cook crowned with the words “We Believe in You.” Four snow white pigeons were released as the doctor’s car passed under the archway by a man atop the arch. (both sides of the arch are shown here)

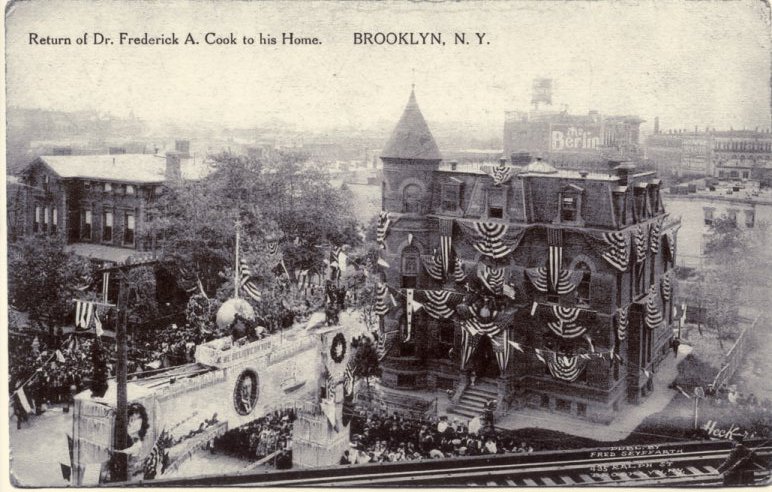

Eventually the motorcade of 200 autos reached the flag-enshrouded Bushwick Club and as the police kept back the crowds, Cook alighted from his car and entered the club. He appeared briefly on the building’s balcony, but despite cries for a speech, he could not be heard and once again simply bowed.

Then, after a light lunch, the doors of the Club were opened, and more than 5,000 passed by the doctor. He could not shake hands with so many, however, so he kept them firmly clasped behind his back as he nodded to each passerby. After three hours the doors of the club were closed to the disappointment of thousands more waiting to get in. Dr. Cook’s day ended at 9:30 PM, with a formal dinner at the club before finally retiring, under police escort, to a suite reserved for his family at the Waldorf-Astoria.

Cook’s momentous day produced very few souvenirs. In fact, the only one I have ever seen is this small celluloid pinback that was doubtless hawked to the enormous crowd waiting for Cook to pass by. Other than that, only some hastily prepared postcards were produced and sold after the events of the day.

This one from the author’s collection is inscribed by Dr. Cook in his distinctive handwriting to a man sharing his given name, “Best Regards from another Fred,” and dated October 3, 1909.

Another showing Cook’s former home on Bushwick Ave. taken from the El viaduct above it and the triumphal arch spanning the street below, was also on sale a few days after the parade.

While Cook was off on his polar expedition, Cook’s wife was forced to sell their three-storey red brick house when her considerable personal funds were lost in the collapse of the Knickerbocker Trust Co. during the Panic of 1907. However, it still stands today on Bushwick Ave., where it is divided into several apartments. Shortly after the parade, it was announced that on the small triangular plot across from it, a monument to the Discoverer of the North Pole would be placed, but due to Cook’s downfall, it was never built. Instead, a monument to the fallen of World War I now occupies that space.

Filed in: Uncategorized.