The Cook-Peary files: February 15, 1910: Dunkle & Loose: a parting letter and a belated appearance

Written on May 21, 2022

This is the 17th in a series examining significant unpublished documents related to the Polar Controversy.

Of all the bizarre incidents of the Polar Controversy, perhaps none has more unanswered questions surrounding it than the Dunkle-Loose affidavits. On December 7, 1909, the day after the so-called “proofs” of Dr. Cook’s polar attainment had been locked away in a Copenhagen bank vault, two men signed a lengthy affidavit at Westchester, NY, claiming that they had been hired by Frederick Cook to fabricate a set of astronomical observations that would convince a panel of Danish scientists about to sit to consider Cook’s proofs that he had reached the North Pole on April 21, 1908. Cook had agreed to send them first to the University of Copenhagen in appreciation for the acclaim and honorary degree he had received there when he landed at the Danish capital in September 1909, after wiring from Lerwick, Shetland Islands, that he had attained the Pole.

The New York Times, which had been vehemently pro-Peary since the start of the controversy, ran the exclusive story December 8; it covered nearly three full pages—by far the most space devoted to any one story on a single day that whole year—that spared its readers no details of the alleged transaction. Those details are related fully in the pages of Cook and Peary, the Polar Controversy, resolved, so there is no need to take them up again here. In the end, after the Danes had examined the materials submitted by Cook, they ruled that they did not contain any proof he had reached the North Pole, but no trace of the calculations Loose said he had provided the doctor, a copy of which the Times had thoughtfully forwarded to Copenhagen, could be found in them either. As a result, although the University’s verdict on the value of Cook’s proofs was devastating to his credibility, the elaborate affidavit became a non-factor in settling the questions surrounding the explorer’s claims.

In their affidavit, the two men claimed that Cook paid them only a fraction of the agreed upon $4,000 price ($100,000 in today’s money) that they asked if their efforts resulted in the explorer’s claim being accepted by the Danes. In all, they received a mere $240 from Cook. What they may have received for their affidavit from the Times is unknown, but considering the length of it, one could reasonably conclude it was considerably more than they got from Cook. The unnatural recall of detail included in their statement indicates they kept very precise notes and that their real intention may not have been to help the explorer prove his claim, but rather was designed to destroy his credibility by exposing his secret efforts to artificially bolster what inadequate original proofs he already had, if any. Even so, that same detail make it unbelievable that the story their affidavits contained was a fabrication. And even Cook’s private secretary acknowledged that Cook had met with Dunkle and Loose.

It is even possible that the pair was put up to it by William C. Reick, an editor at the Times who had an old score to settle with his former employer, James Gordon Bennett, owner of the rival New York Herald. Letters in the National Archives II between Reick, Bridgman and Peary suggest as much. The Herald was the most important paper in the city at the time, and had printed Cook’s original dispatch claiming his discovery, and it also ran his detailed serialized account of his feat. It therefore had a large stake in the establishment of the legitimacy of Cook’s claim, which from its first announcement had been questioned by pro-Peary forces, and it had much to lose if Cook’s claim was discredited.

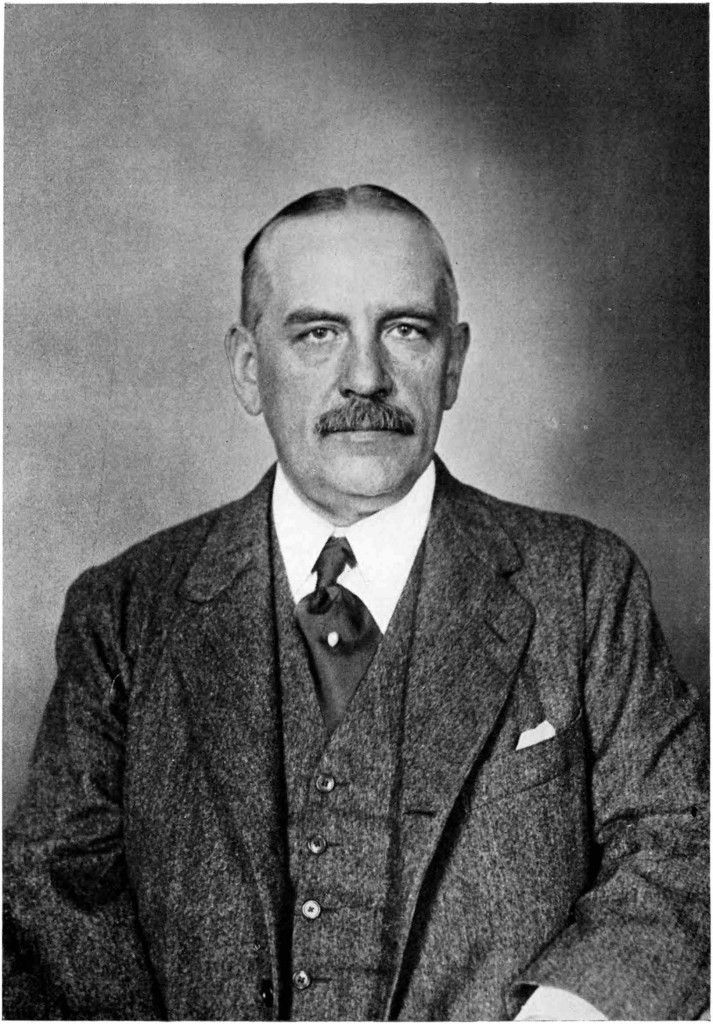

William C. Reick

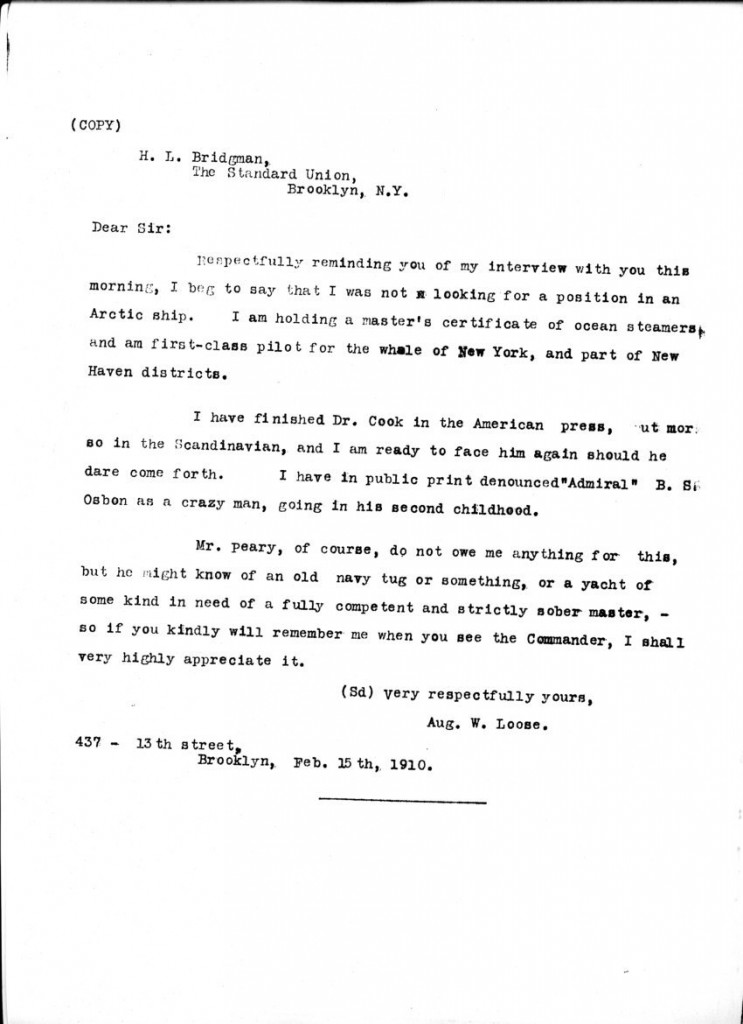

Whatever they got from Reick, it was apparently all they got. As a result of the unwanted publicity, George W. Dunkle, who worked for a New York insurance company, and who had originally approached Cook with a proposition of insuring his original “proofs,” was dismissed from his job. August Wedel Loose, an itinerant sea captain who Dunkle introduced to Cook, and who claimed that he worked up the bogus calculations, seems to have fared little better. In January 1910 he wrote to Herbert L. Bridgman, editor of the Brooklyn Standard Union and secretary of the Peary Arctic Club, which bankrolled Peary’s attempts to reach the North Pole:

Shortly after, Loose left the United States, never to be heard of again.

Not only are the exact origins of the Dunkle-Loose affidavits shrouded in mystery, but also are the men themselves. After their 15 minutes of fame in the Times, the pair dropped totally from sight—literally and figuratively. During the years of research I spent in preparing Cook & Peary, I never saw a single photograph of either man. None appeared in the New York Times, or apparently anywhere else, until recently I recovered a copy of a press photo from an Ebay auction site that sells off photographs from the morgues of various defunct newspapers. As far as I know, it is published here for the first time and gives us our first look at these two slippery characters in the flesh. (Loose is the one with the mustache on the left).

The origins of the picture can be surmised from the back of the photo, which bears this penciled inscription: “Capt. Loose and Dunkle who revealed Dr. Cook’s effort to have them prepare a ‘log’ for him.” The photo is backstamped “Nov. 16, 1910,” or nearly a year after the New York Times story broke. Apparently, it came from the morgue of the Cleveland Press, indicated by another backstamp, which reads: “N.E.A. Reference Department, Press bldg, Cleveland.” N.E.A. stands for the Newspaper Enterprise Association, a syndication service started in 1902 that supplied comics and pictorial matter to hundreds of newspapers nationwide. It is the only such syndication service still in business.

The Loose letter is in the Peary Family Papers at NARA II, College Park, Md. The photo of Dunkle and Loose is the possession of the author.

Filed in: Uncategorized.