The Cook-Peary Files: The Barrill Affidavit: Part 1 – “Impossible do better.”

Written on June 13, 2022

This is the 18th in a series examining significant unpublished documents related to the Polar Controversy.

In all of the Polar Controversy, perhaps the most telling piece of evidence produced against Frederick Cook’s claim to have discovered the North Pole had nothing to do with his 1908 polar expedition. It came instead out of his previous expedition to Alaska in 1906, which was aimed at the first ascent of the tallest peak in North America. At its conclusion, he announced that he and his burly packer, Edward N. Barrill, were the first to reach the summit of Mt. McKinley on September 16 of that year. That claim led directly to Dr. Cook being feted at the annual dinner of the National Geographic Society in Washington, being elected the second president of the Explorers Club of New York, two well-remunerated articles in Harper’s Monthly Magazine and a contract to write a book about the exploit. It also led indirectly to his obtaining the backing of the wealthy gambler John R. Bradley for his attempt to reach the North Pole the following year. But in its immediate wake, it had left Cook flat broke.

Cook’s Alaskan journey had been sponsored by the millionaire Philadelphia saw manufacturer, Henry Disston, who gave him financial support in exchange for Cook’s organizing a big game hunt for him at the expedition’s conclusion. However, Disston had a change of mind, failed to show up for the hunt, and so did his money. But Cook had already contracted to rent a pack train for the prospective hunt, and when he tried to cancel this arrangement without paying, he was hauled into Alaskan court and lost, wiping out all his cash on hand. As a result, he could only give the men he had hired to enable his attempt to climb the mountain promises to pay in the future rather than what he owed them then and there. When Cook went off with Bradley to the Arctic in July 1907 and didn’t come back, all those debts were still outstanding, and remained so until after his return to the United States in September 1909, after claiming he had attained the North Pole on April 21 of the previous year. Those unpaid debts were to be his undoing as it turned out.

As there were doubts from his first announcement of his polar conquest, there had also been doubts in Alaska that Cook had actually made the summit as he claimed. Some of these were simply the result of envy. Many Alaskans thought the mountain unclimbable, and resented the idea that some “effete” Easterner from “the Outside” could have come and so easily plucked the prize that the Sourdoughs and Pioneers of Alaska coveted for themselves. No one had real evidence that Cook had not actually done the deed, but there were some reasons that fed these suspicions beyond pure jealousy. Cook’s timetable for the climb, which he gave before a meeting of the Mazamas in Seattle shortly after his return, seemed too short and too pat for the accomplishment of such a titanic undertaking. The only member of Cook’s own expedition who voiced public doubt, however, was Herschel Parker, who had returned from Alaska after being assured by Cook that no further attempt to climb the mountain would be made that season. But after Cook met with him upon reaching New York, Parker seemed persuaded that Cook had indeed climbed the mountain, but the nature of his accomplishment, Parker felt, was only that of a sporting event, with few of the scientific results Parker hoped to obtain from the conquest.

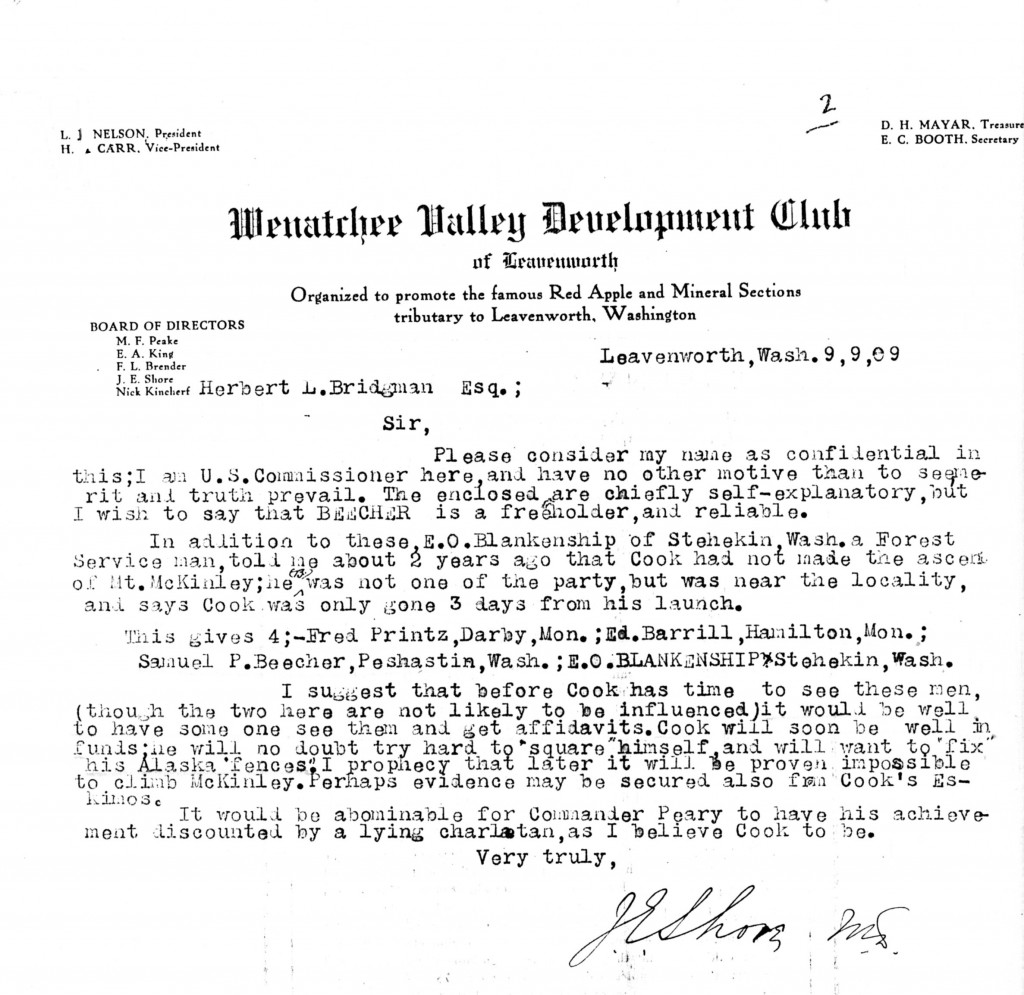

But as the Polar Controversy grew between Cook and Robert Peary over who had been first to the Pole, many saw opportunities developing to exploit their former associations with Frederick Cook in Alaska and get their back pay they were due—or perhaps even more. J. E. Shore, a U.S. Commissioner in Leavenworth, WA, alerted Herbert L. Bridgman, Secretary of the Peary Arctic Club, that Cook’s unpaid debts might provide useful fodder to use against Cook.

Bridgman passed on Shore’s letter and enclosures indicating that several of Cook’s former expedition members had complained of Cook still owing them back wages to General Thomas H. Hubbard, the Peary Arctic Club’s president. Hubbard immediately engaged his law correspondent in Tacoma, James M. Ashton, to act on his behalf to obtain affidavits concerning what they knew about Cook’s Alaskan claims. After all, if it could be shown that Cook had not actually reached the summit of Mt. McKinley, that would set a glaring precedent for a dishonest claim to have reached the North Pole. No doubt, however, Hubbard realized that the key figure among those named by Shore in his letter was Barrill, because he alone had been with Cook in the days immediately before and after September 16, 1906, and so he alone knew for sure the truth or falsity of Cook’s claim to “the top of the continent.”

James M. Ashton

Ashton later reported that he had indeed been hired by Hubbard to seek out these men, but denied his efforts had a predetermined agenda. “I received word from Gen. Hubbard to ascertain the exact truth concerning Dr. Cook’s climb of Mount McKinley and had not the remotest idea what side I was on or would be on,” he told the New York Globe on October 16. “I sent [Walter] Miller [who had been the photographer on Cook’s 1906 expedition] to Barrill and other members of the expedition and had them brought to Tacoma. They were all carefully examined. Barrill spoke openly and squarely from the start.” However, this is not exactly the way things actually went down.

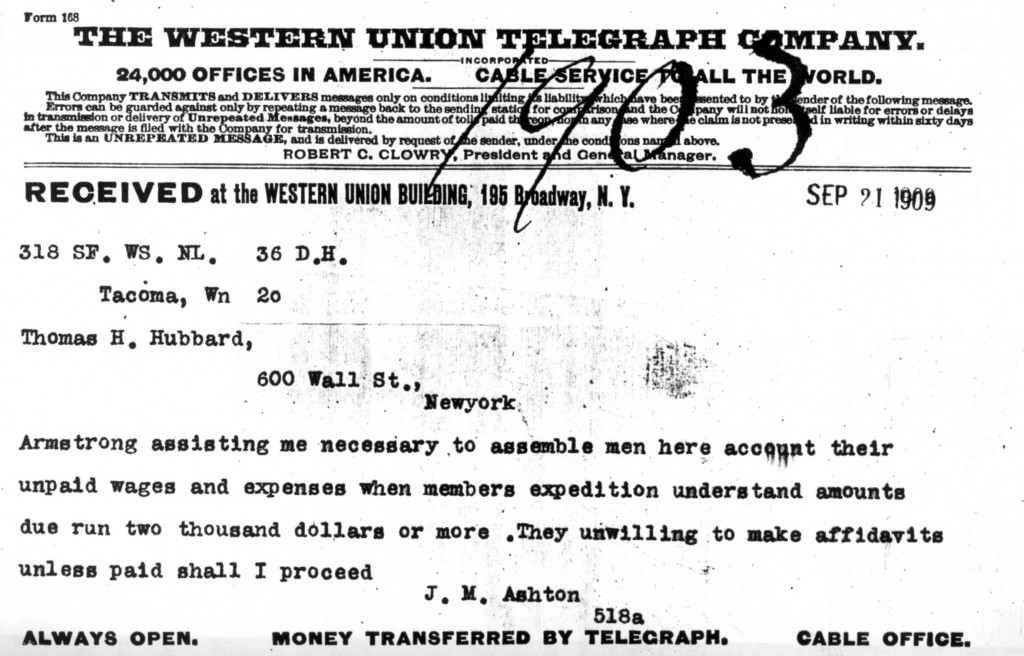

As Ashton met with the various expedition members, he kept up a running report on his progress via telegraph with Hubbard. On September 21 he reported:

[“Armstrong” was William Armstrong, one who assisted Cook with his 1906 pack train.]

[“Armstrong” was William Armstrong, one who assisted Cook with his 1906 pack train.]

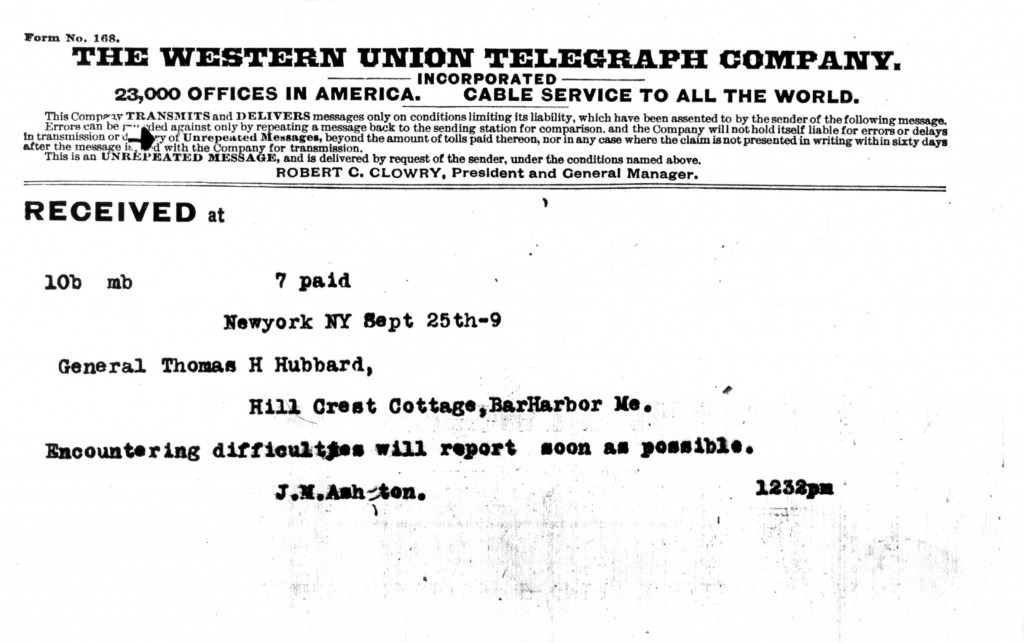

September 25:

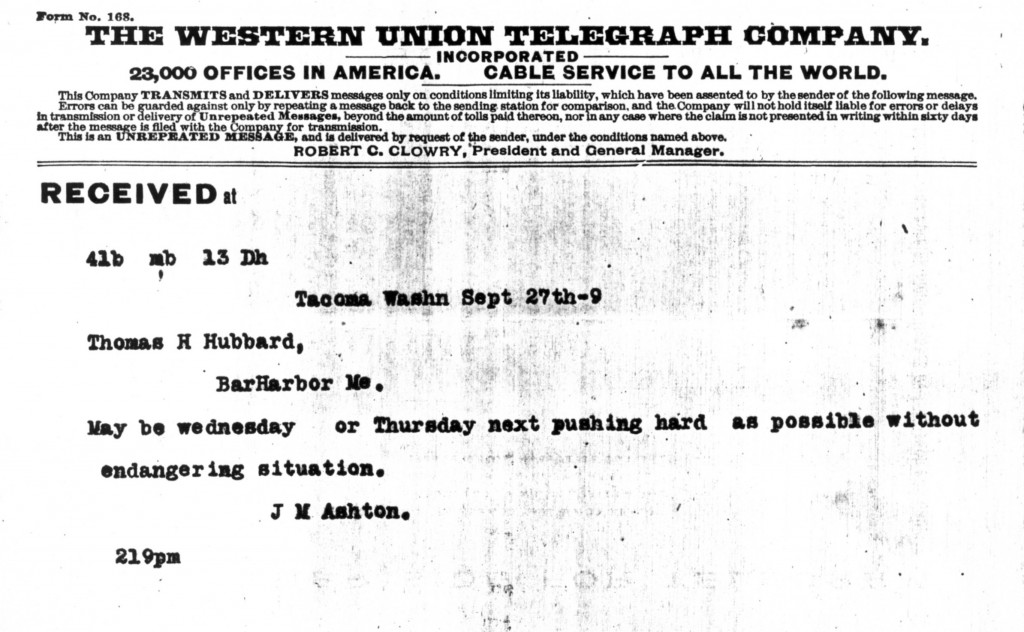

September 27:

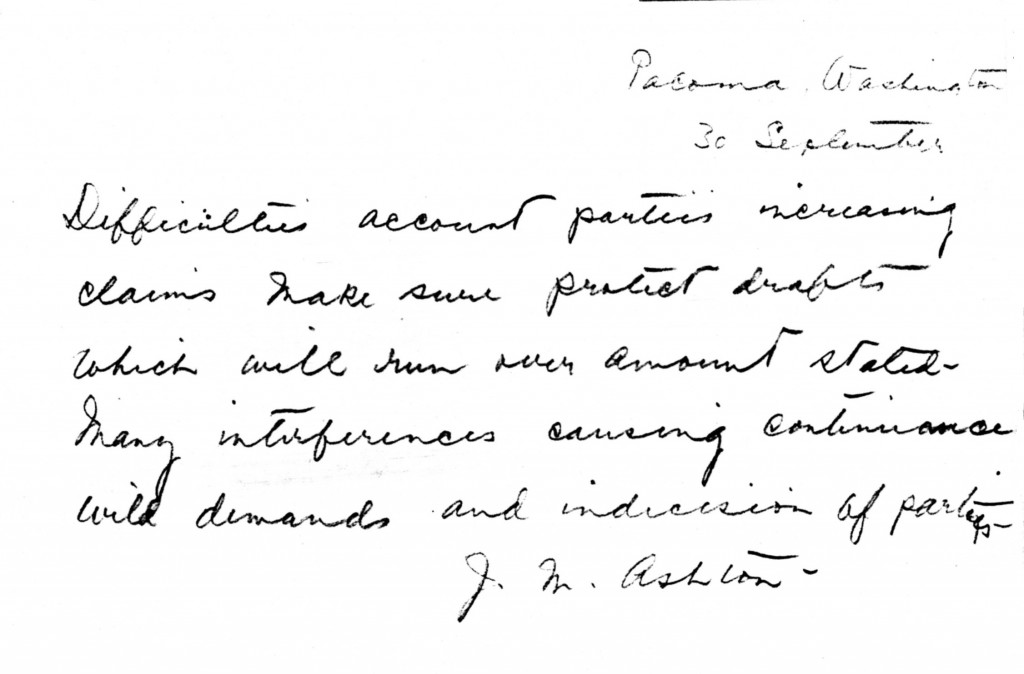

September 30:

[Difficulties account parties increasing claims Make sure protect drafts which will run over amount stated [i.e. $2,000]. Many interferences causing continuance wild demands and indecision of parties.]

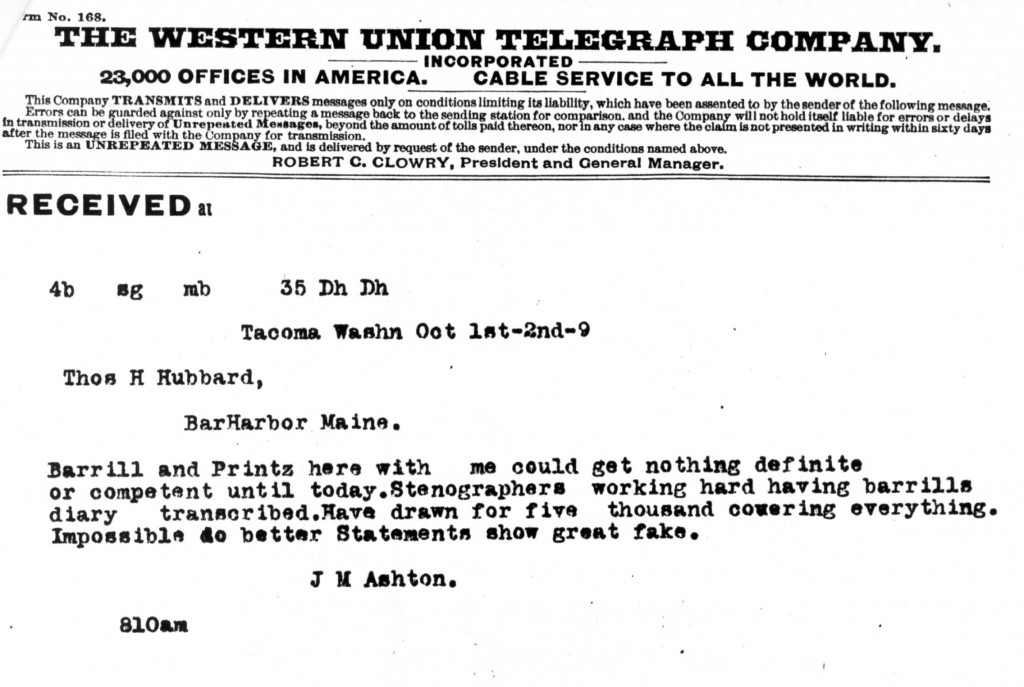

October 1:

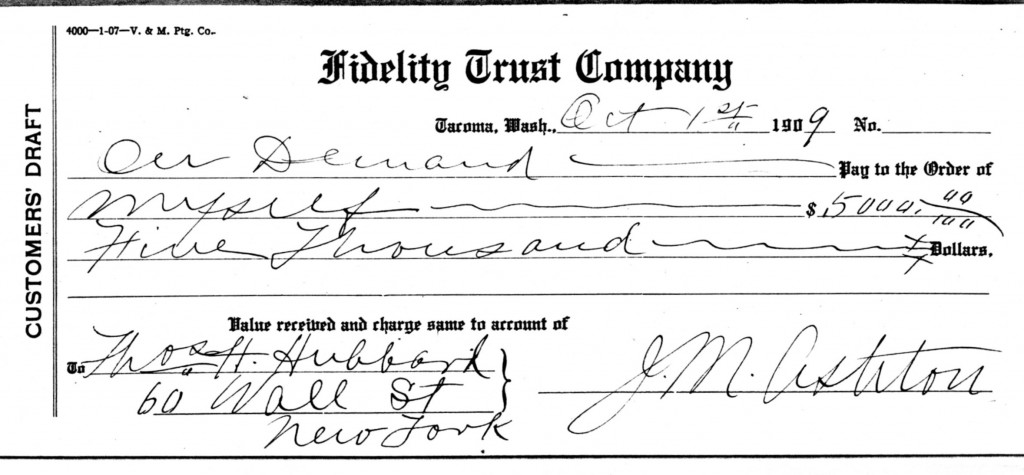

On that day Ashton drew a customer’s draft for $5,000 on the Fidelity Trust Company of Tacoma, charged to the account of Thomas H. Hubbard, 60 Wall St., NY.

All the items reproduced here except the portrait of James Ashton are in the Peary Family Papers at National Archives II, College Park, MD.

Filed in: Uncategorized.