The Cook-Peary Files: The Barrill Affidavit Part 2: Ed Barrill and his affidavit go to New York

Written on July 28, 2022

This is the 19th in a series examining significant unpublished documents related to the Polar Controversy.

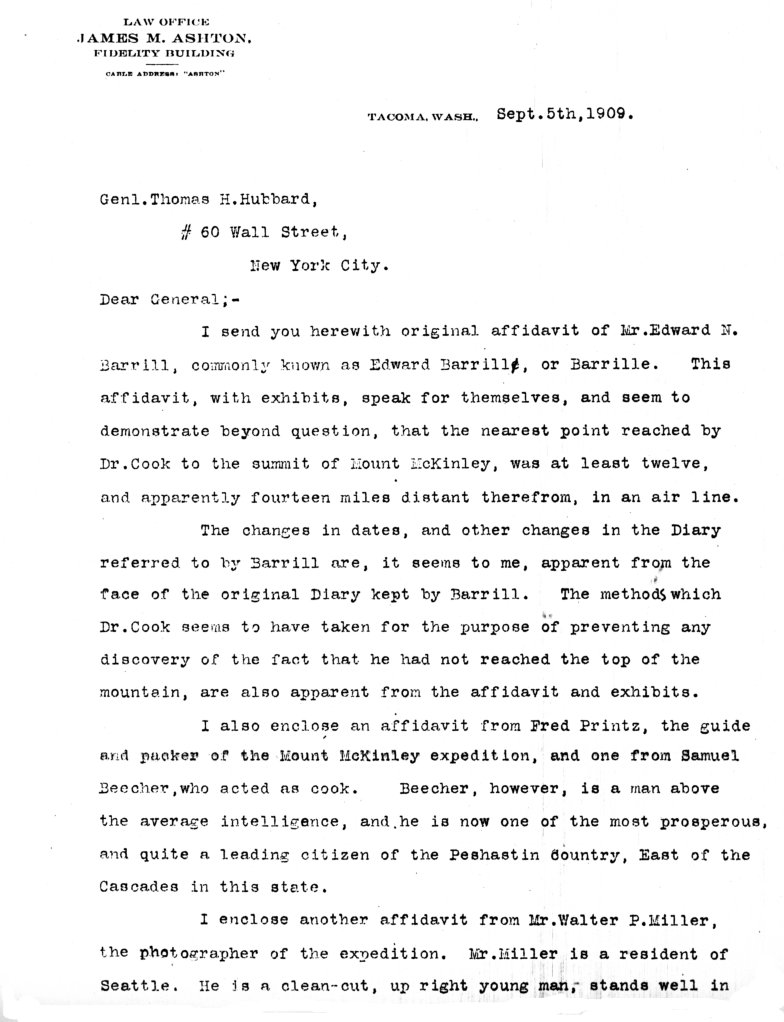

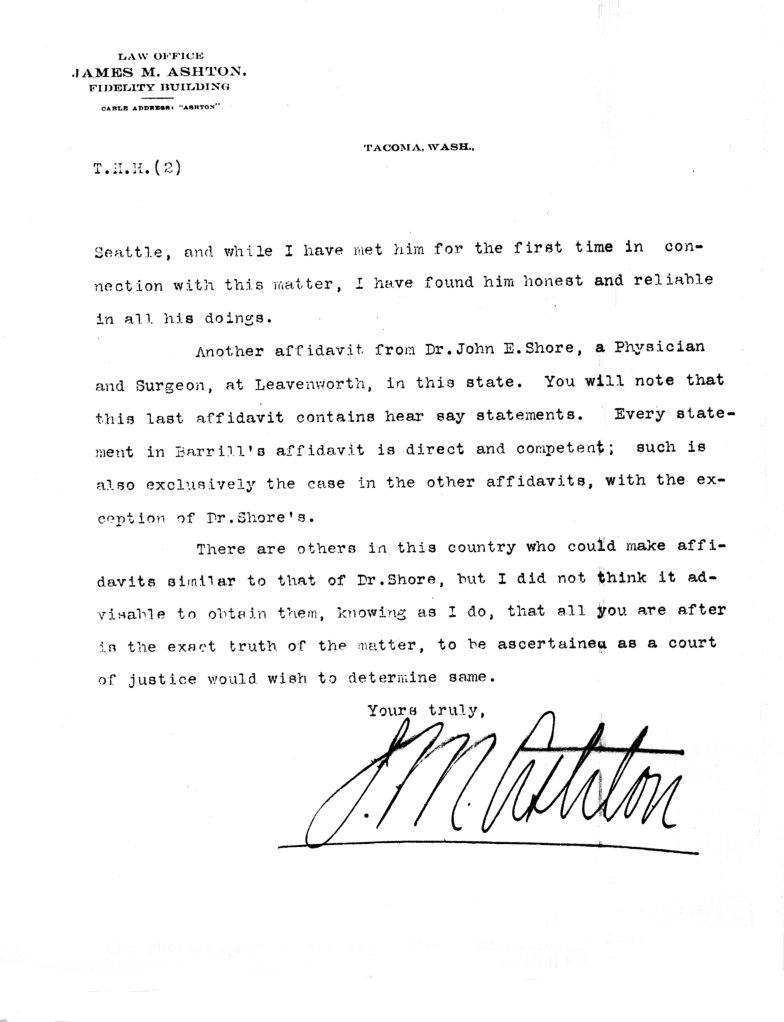

On October 5, after he had taken affidavits from four others bedsides Barrill, Ashton wrote to General Hubbard, misdating his letter by a month as September 5.

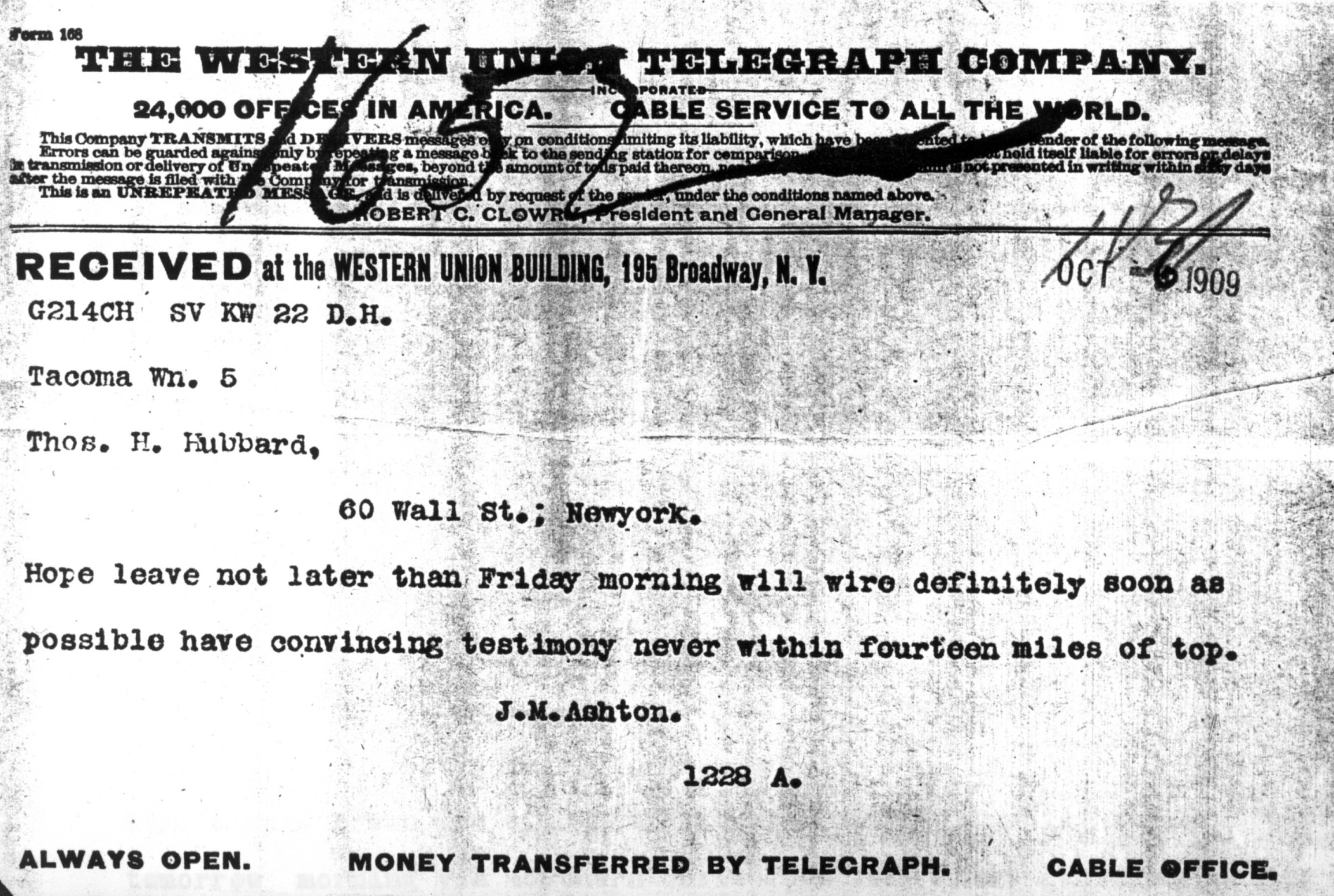

Ashton had proposed to General Hubbard that Walter Miller bring the affidavits he had obtained to New York, but Hubbard insisted Ashton, himself, bring them. It would take a few more days to wind up the business, Ashton thought, and wired Hubbard on October 6 that he would be leaving on the Burlington Northern’s Lake shore Century, Friday, October 8.

Meanwhile, the New York Herald, which first announced Cook’s North Pole claim to the world and was then running his serialized account of his conquest, had gotten wind of Ashton’s activities. On October 12th the paper reported from Missoula, Montana: “Edward Barrille, the guide who accompanied Dr. Frederick A. Cook to the top of Mount McKinley, Alaska, in 1906, has been approached, it is asserted here, with an offer of $5,000 to make an affidavit to the effect that the Brooklyn explorer never completed the ascent.”

When the question was put by reporters in New York as to whether an affidavit had been bought, General Hubbard dismissed such reports as “all bosh.” “No money was given to him for his signature,” the general maintained.

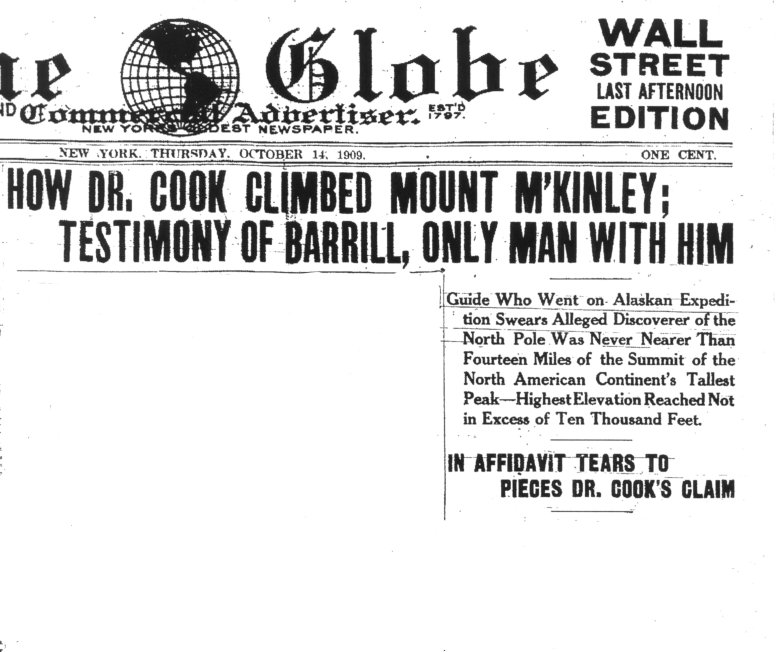

Hubbard was eager to publish Barrill’s statement, but when Ashton arrived, Barrill’s affidavit was intentionally held back until Peary published his “proof” that Cook was a liar in the form of alleged testimony given by the only two witnesses along on his polar journey, the two Inuit, Etukishook and Ahwelah. They were said to have stated that they had never been at the North Pole, and in fact had never been out of sight of land on their entire journey with Cook. This statement was slated for release by the Peary Arctic Club on October 13, so publication of the affidavit was delayed to the next day, October 14. In that way the two statements, Peary and Hubbard hoped, would be the one-two punch that would be a knockout blow to Cook’s credibility.

Barrill’s affidavit was printed in full in the pages of Hubbard’s own newspaper, The New York Globe and Commercial Advertiser.

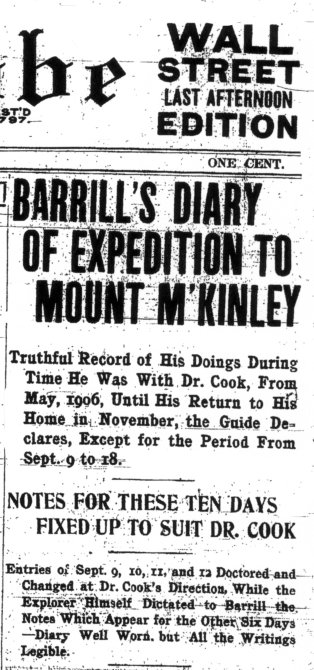

This was followed the next day by a complete transcription of Edward Barrill’s entire 1906 diary.

The fact that the account sworn in the affidavit did not match that written by Barrill in 1906 was explained away by saying Cook had induced Barrill to doctor his diary to match Cook’s eventual account. Thus Barrill admitted he had conspired to lie at Cook’s direction.

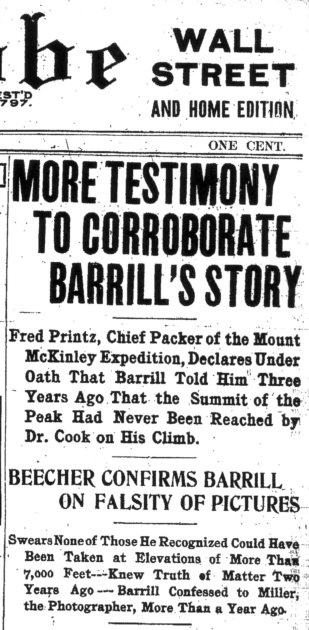

On the 16th, the rest of the affidavits secured by Ashton, those of Fred Printz, Walter Miller, Samuel Beecher and John Shore, were printed in the Globe.

Ed Barrill, himself, accompanied by his wife, Fanny, had followed closely behind his sworn statement, arriving in the city on October 12th . Hubbard brought him to his office, where he conducted a personal interview. The general promised to make Barrill available to a committee of the Explorers Club, of which Peary was the sitting president, that was investigating the doubts being expressed about Cook’s McKinley ascent, which he did the next day at the rooms of the Century Club. Barrill was not made available to the New York press, however. When asked, Hubbard denied knowing where Barrill was staying, and Frederick Dellenbaugh, one of the Explorers Club committee members, said he knew, but refused to disclose Barrill’s location. On October 15th, Hubbard sent word that he saw no need for Barrill to remain longer. Barrill went home with alacrity, never to return, without giving a single press interview.

But in an interview published in the New York Times, General Hubbard elaborated on his intentions in obtaining the affidavits and again discounted any speculation on money being exchanged. He told the Times’ reporter that Barrill “had turned over the diary and made the affidavit impugning Dr. Cook’s word without any monetary inducement as Dr. Cook had intimated in interviews at Atlantic City.” “Barrill told me,” the general went on, “he was tired of hearing Dr. Cook say he had climbed Mount McKinley. That was why he was willing to make the affidavit and give up his diary. He was not coaxed with money. He did it all of his own free will.” And when the reporter persisted, saying, “Dr. Cook has suggested that $5,000 was paid as a bribe to get the affidavit,” Hubbard answered, “Does he? Well let him prove it. It is not so. The affidavit was obtained exactly as every other affidavit is obtained. It was a simple piece of business—that’s all. And what’s more, every word in the affidavit is true.”

Many of the Globe’s readers and other neutral parties remained unconvinced that this was so, however, pointing out that in his affidavit Barrill openly admitted he had been willing to conspire to support a lie concocted by Cook by assenting to it himself. As a result, the immediate impact of Hubbard’s large cash outlay, an amount equivalent to $150,000 today, was far smaller than he and Ashton expected.

Ashton’s misdated letter and telegram are in the National Archives II, College Park, MD

Filed in: Uncategorized.