The Cook-Peary Files: The “Eskimo Testimony”: Part 2: Peary’s Proofs

Written on November 11, 2022

This is the latest in a series of posts that publish for the first time significant documents related to the Polar Controversy.

At first, General Hubbard seemed reluctant to become involved in the developing controversy. He wrote to Peary: “About the Cook matter—you know the man and know what he probably has in the way of proofs, and you know what you have, and, for these reasons, are the one competent judge as to the treatment the matter should receive. I hesitate to make any suggestions.” But Peary quickly proved he wasn’t competent in meeting the issue of Dr. Cook.

In his first interview with the Press in a fish loft at Battle Harbour, Labrador, Peary reiterated that he had proof Cook had not been to the Pole, but refused to disclose its nature. All he had presented so far was his bald statement that the Inuit who had accompanied him denied his story. Various parties familiar with Inuit culture and psychology thought this inadequate, however. Dillon Wallace, a member of the Explorers Club who had made several trips to Labrador, said “I am rather surprised to see Commander Peary quoting the Eskimos to the effect that Dr. Cook never reached the pole. Their whole idea of life is to say what pleases. . . They are all in awe of Peary and would not like to offend him. They would, for the sake of being agreeable, willing declare that white snow was black.” And Dr. Thomas Dedrick, who had been Peary’s surgeon on his 1898-1902 expedition, and who was intimately familiar with Polar Inuit culture, agreed: “Mr. Peary’s statement that the Eskimos gave him these facts must be judged in the light of the condition under which the statements were made. . . . To please Mr. Peary, in which art of pleasing the Eskimo is most adept, the Eskimos, in expectancy of gifts, could easily say or have their remarks twisted to the semblance of saying that Dr. Cook did not get very far toward the pole. Here was a man on the spot with a ship. Dr. Cook was but a memory to the Eskimos.”

Henry Rood, representing Harper’s Magazine, was one who interviewed Peary in the Labrador fish loft. As a personal friend of Peary’s, he was given papers to deliver to General Hubbard, while Peary continued to bombard the general with telegrams.

When Peary finally arrived back in the United States at the end of September, he met Hubbard at his home in in Bar Harbor. On the train going back to Portland, Peary gave a rambling interview that the Press dubbed his “fourteen points.” Among those he mentioned as evidence against Cook’s claim, besides that the Inuit had said he had not gone out of sight of land, were the fact that Cook failed to retrieve the record at Cape Thomas Hubbard, which Peary left there in 1906, his negative opinions of Cook’s sledging abilities, various criticisms of his provisions and equipment, and his decision to leave his records and flag with Harry Whitney at Annoatok. This last fact rebounded negatively on Peary because when Whitney returned without Cook’s things, it was learned that Peary had refused to allow Whitney to bring them aboard the Roosevelt, and instead ordered that they be buried in a cache near Etah. Peary’s “fourteen points” interview was too much even for his supporters. Henry Rood wired Peary that “you are obviously being misquoted,” and suggested that Peary give no more interviews to the Press.

The public and the Press were appalled at Peary’s behavior and continued attacks on Cook while refusing to provide any hard evidence for them. As one editorialist wrote: “The further this most deplorable controversy is carried the worse is Commander Peary made to appear. It is quite clear now that his mood after returning to Etah from the pole and hearing that Dr. Cook had reached the goal ahead of him was – and still is—blind fury, breaking the bounds of good judgment and good taste, indeed, of ordinary discretion.”

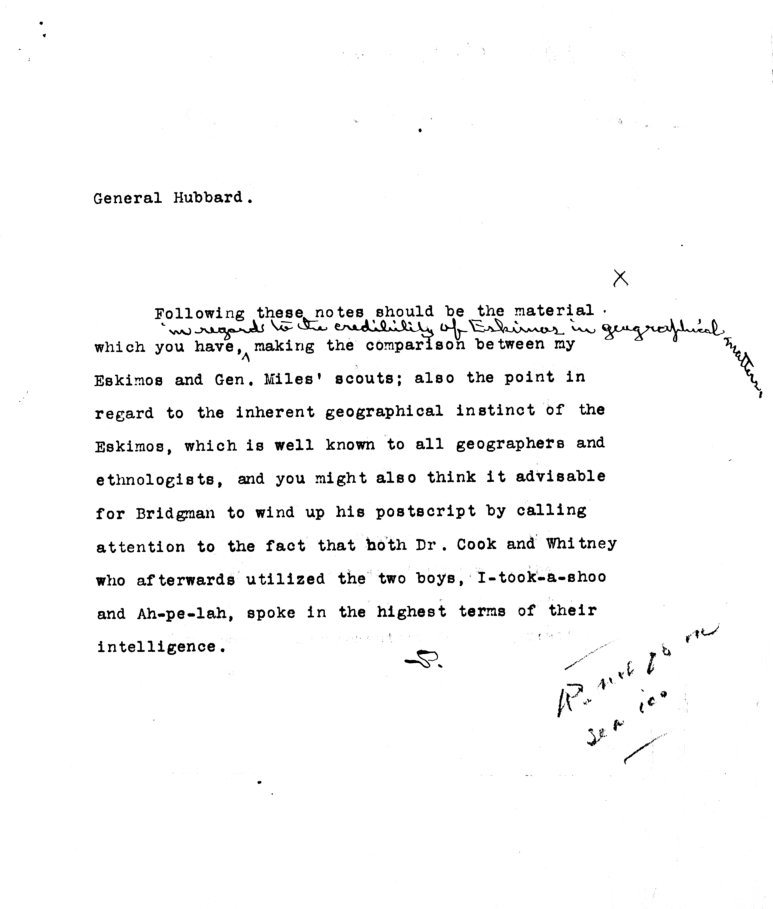

The “fourteen points” interview led to a gag order on Peary, who retired to his summer home on Eagle Island in Casco Bay. Hubbard then became Peary’s spokesman from that point forward. But even so, Peary continued to send him almost daily letters. In one, he went over a number of points concerning the proof he would release, a draft of which he had already sent Hubbard. The first had to do with the crucial matter of the Inuit ability to trace such a route, and their credibility in doing so.

On October 3, Peary met Hubbard again on the platform of the Portland railway station. The two men walked up and down the platform talking together under the glaring arc lights; occasionally they stopped while Peary emphasized a point. General Hubbard was seen to accept a large white envelope from Peary on which he made a few notes. Hubbard then returned to New York and went into conference with other members of the Peary Arctic Club. After the meeting Hubbard announced that the unanimous decision of the Club was to release Peary’s evidence against Cook to the newspapers the following week.

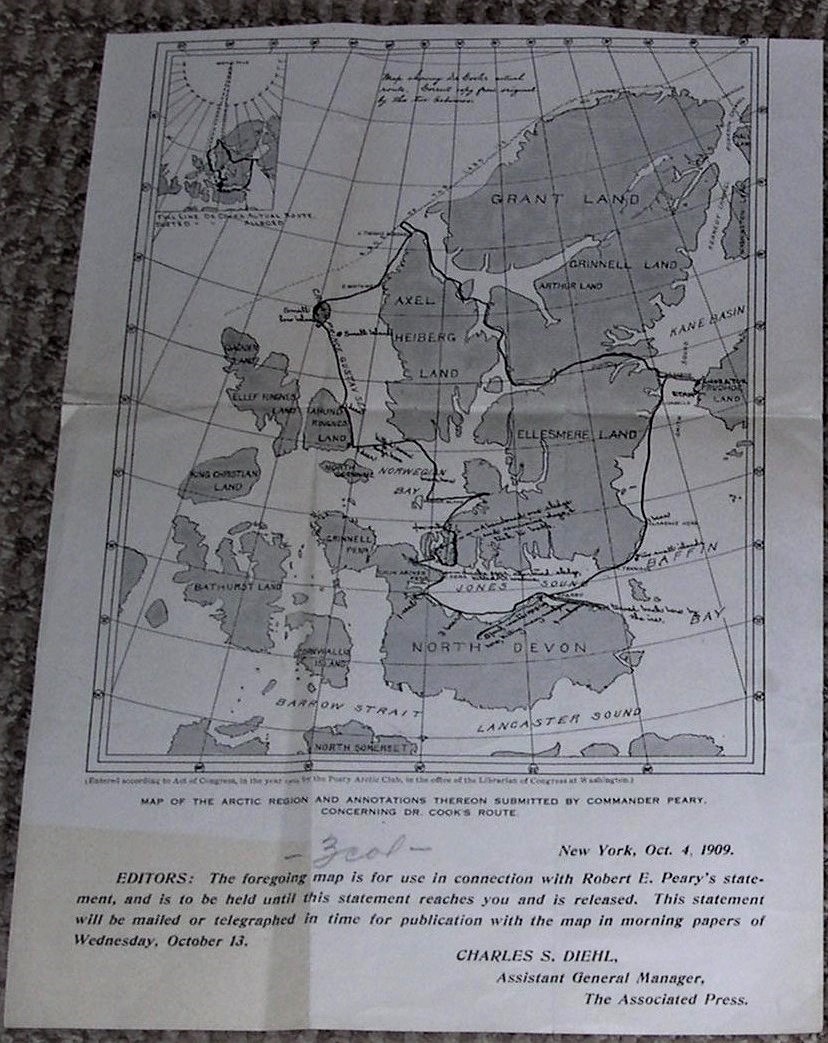

Through the auspices of the Associated Press, a map, allegedly drawn by his two Inuit companions showing the actual route taken by Dr. Cook on his polar attempt, was mailed out to all the newspapers that were members of the AP. At the bottom it enjoined any release of the map or the forthcoming statement, when it arrived, until the morning of October 13.

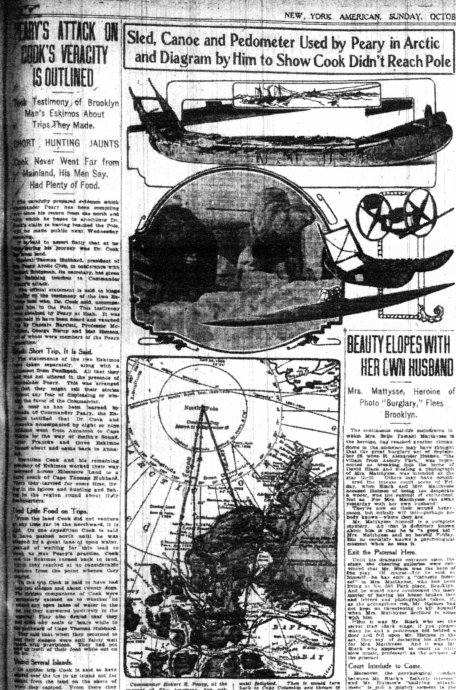

But William Randolph Hearst broke faith with the embargo. The New York American and some other papers controlled by Hearst ran a detailed summary of Peary’s forthcoming statement with its own map on October 10.

Herbert Bridgman, the Peary Arctic Club’s secretary, appealed to the AP’s superintendent to sanction Hearst. But he replied that this was out of the AP’s jurisdiction, because it was the Peary Arctic Club which had copyrighted the Peary statement and map, not the AP. He also claimed that the copyrighted statement had not been delivered by the date the American’s summary was published (though the map had). Just where the American got the statement was not speculated upon. Although Bridgman might have considered seeking relief from the courts, but the cat was already out of the bag, and he apparently just dropped the matter.

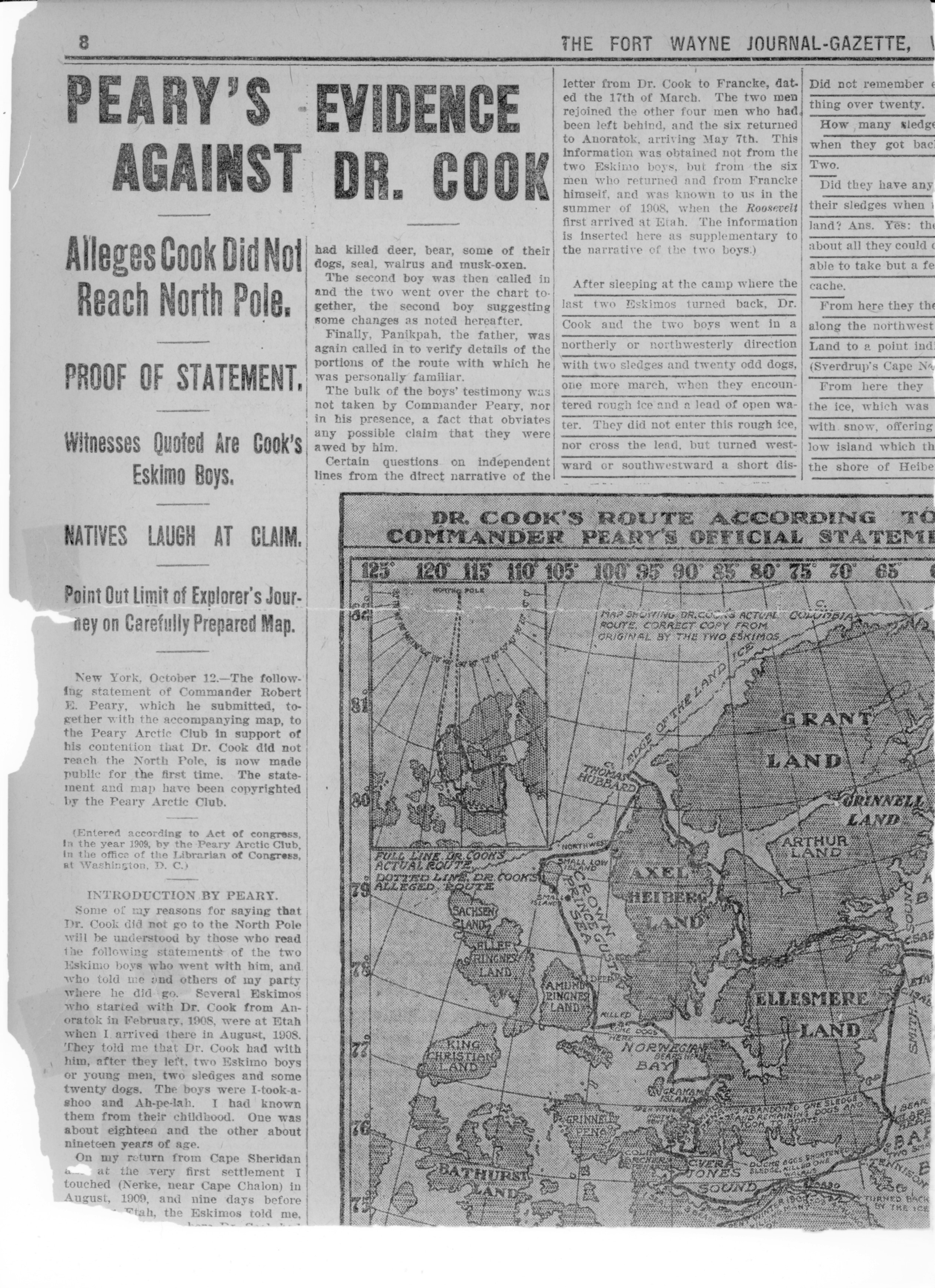

The official release of Peary’s statement came, as planned, on October 13.

The story consisted of three parts: an introduction signed by Peary concerning the manner in which the Inuit statement was obtained, the statement itself, signed by Peary and four other members of Peary’s expedition, George Borup, Matt Henson, Donald MacMillan and Robert Bartlett, and an explanatory follow-up written by Herbert L. Bridgman, containing some of the points Peary had made to General Hubbard in the letter shown above.

According to the statement, the Inuit said that they had proceeded to the tip of Axel Heiberg Land, as Cook had said he had done; they had camped there for some days and then, with two other Inuit, had started north over the pack. These two had returned after one day on the ice. Cook and the remaining two Inuit had camped on the ice for one more day, turned west, then south, eventually reaching Cape Northwest on the west coast of Axel Heiberg Island. The accompanying map claimed to show the route taken from Cape Northwest: “They went west across the ice, which was level and covered with snow, offering good going, to a low island, which they had seen from the shore of Heiberg Land at Cape Northwest. On this island they camped for one sleep.”

From this point, the statement said, the three had traveled southward along the eastern coast of Amund Ringnes Island. After that, in most all particulars, the Inuit story, according to the statement, was broadly similar to Cook’s account, except that the Inuit said they did not cross North Devon Island to reach Jones Sound and that two small islands were discovered southeast of Ellesmere Land on their trek toward Annoatok in the spring of 1909. The full published statement with the accompanying map, as published, can be read at this website: https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn83030214/1909-10-13/ed-1/?sp=1 or at the New York Times archives site: https://www.nytimes.com/1909/10/13/archives/cooks-route-far-from-pole-his-eskimos-say-peary-submits-their.html

Many papers which printed Peary’s statement also published counter arguments by Cook’s supporters. After the dust settled, many found Peary’s much delayed and ballyhooed statement distinctly anti- climactic, as an editorial in the Rochester Post-Express was typical:

Even Peary’s firm supporters doubted that the statement would end the matter. “There might be circumstances under which the evidence of these young men would be of greater value,” admitted Cyrus Adams of the New York Sun, but under the circumstances it was obtained, “It is not very likely that . . . their evidence will count for very much in the final settlement of the controversy.”

Peary’s note to Hubbard is in the Peary papers at NARA II; the hitherto unknown AP letter was recently recovered by Darrell Hartman, the author of a forthcoming book about the NY Press at the turn of the century to be published by Viking, in the files of the Explorers Club of New York, who supplied a copy. He also supplied the image of the NYA story from October 10, 1909, which he retrieved from the New York Public Library.

Filed in: Uncategorized.