The Cook-Peary Files: The “Eskimo Testimony”: Part 3: The Eyewitnesses

Written on December 15, 2022

This is the latest in a series of posts that publish for the first time significant documents related to the Polar Controversy.

Dr. Cook’s claim to having attained the North Pole was in the nature of an unwitnessed assertion. True, Cook had with him two Inuit, Etukishuk and Ahwelah, but they were incapable of verifying that Cook had actually reached his goal. This is not to diminish them. They were ideal traveling companions on such a journey, being masters of Arctic travel and survival, which Cook gave them full credit for. In fact, he acknowledged they were superior to any white assistant he could have taken in this regard, but they had no Western scientific skills by which they could verify in any concrete way Cook’s assertion. The only other eyewitness besides these two Inuit was Rudolph Franke, who overwintered with Coook and accompanied him on the first part of his polar attempt. But Franke had been sent back after the first three days when Cook was on a small island off of Bache Peninsula, more than 500 miles from the North Pole. Although Franke truthfully reported this portion of Cook’s journey (more truthfully than Cook did himself, as it turned out), he could say nothing about where Cook went after that. Even if he had gone farther, he, too, lacked the scientific skills necessary to verify Cook’s claims.

Therefore, it was only Frederick Cook who knew for sure if he had reached the North Pole. So, what did Cook himself say? And what did he tell the Inuit and others before he wired his first account to world from Lerwick, Scotland, on September 1, 1909?

Of course, My Attainment of the Pole contains his version of his polar journey in circumstantial detail, and in it, of course, he claimed that he indeed did reach the North Pole on April 21, 1908. In that book Cook also referred to Peary’s interview with Etukishuk and Ahwelah that resulted in his “proof” against him that was published on October 13, 1909. (see the previous post). These references can be found in entries in the book’s index on pages 12, 34, 206, 452 and 488.

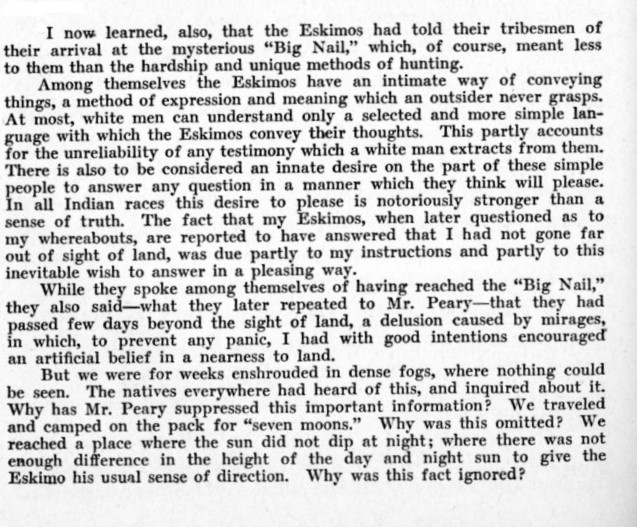

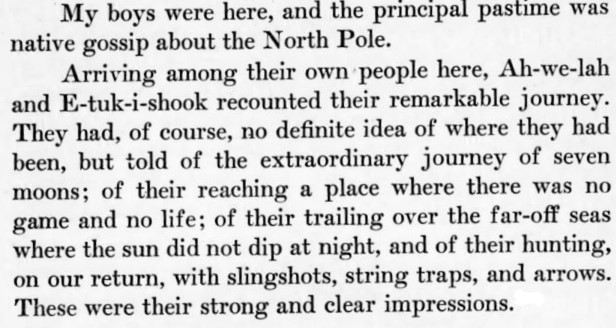

Cook claimed in numerous subsequent interviews that, to keep down the tendency of Inuit to panic when they lost sight of land, he encouraged his two companions to believe that the numerous mirages that are common in the Arctic were actual land, and thus the Inuit told Peary that they had never lost sight of it. However, this seems hardly credible. Inuit were masters of their environment. They knew how to read weather signs, interpret ice and snow conditions, and distinguish mirage from reality. Their lives literally depended on these skills.

There seems no doubt that wherever Cook turned back, he told his companions he was doing so because he had reached the North Pole. The Inuit had no such Western mathematical concept as “The North Pole,” and never understood the desire of so many whites to reach it. When shown it on maps, they called it “The Big Navel,” because it appeared to them as a point at the center of concentric circles. This was either misunderstood or corrupted into “The Big Nail” Cook refers to in the subsequent quote from My Attainment of the Pole. Cook talks at length in his book about his companions’ initial excitement when told they had reached their goal. They expected to see something different, even amazing, but he says, they soon showed disappointment that the place looked exactly the same as any other spot on the polar pack ice. Cook also claimed a number of times that he cautioned his companions not to tell Peary they had been at the Pole, and said that their later statements to him reflected his instructions to them, with which they kept faith.

Cook’s most substantial refutation of Peary’s proof came in a footnote on page 452:

But again, Cook was being disingenuous. Cook had spent two winters with the Inuit in northern Greenland, and had visited them on three other separate occasions. He was an acute observer and had grown familiar with their psychology and cultural norms. He knew swearing an Inuk to secrecy was absolutely futile. Lying was culturally disapproved, and secrecy was as well. Cook knew that his Inuit would tell their fellow tribesmen what Cook had told them as sure as the sun would rise in February.

So, he told the Inuit of his attainment, but what did he say to others after he returned to his winter base in April 1909? Early in his controversy with Peary, Peary suggested it was suspicious that Cook had never told anyone he had reached the North Pole when he returned to Annoatok. There he encountered three white men, Harry Whitney, a rich hunter who had come north with Peary in 1908 and who had spent the winter in Cook’s box house at Annoratok to bag Arctic trophies, and John Murphy and Billy Pritchard, bos’un and cabin boy of the Roosevelt, respectively. After a period of recovery from his grueling journey from Cape Hardy, where he had wintered, Cook told Whitney in confidence, “I have been to the Pole.” Whitney, Cook relates, offered his congratulations. Cook asked Whitney not to tell this to Peary when he returned, however. He didn’t tell him to lie, but, if questioned, asked him to just say Cook had beaten Peary’s 1906 Farthest North record. Cook then discovered that Billy Pritchard had overheard his conversation with Whitney and swore him to secrecy as well. Peary had left Pritchard and Murphy at Etah to trade Cook’s supplies for valuable furs over the winter. Murphy was absent there on this assignment at the time of his conversation and so did not know of Cook’s claim.

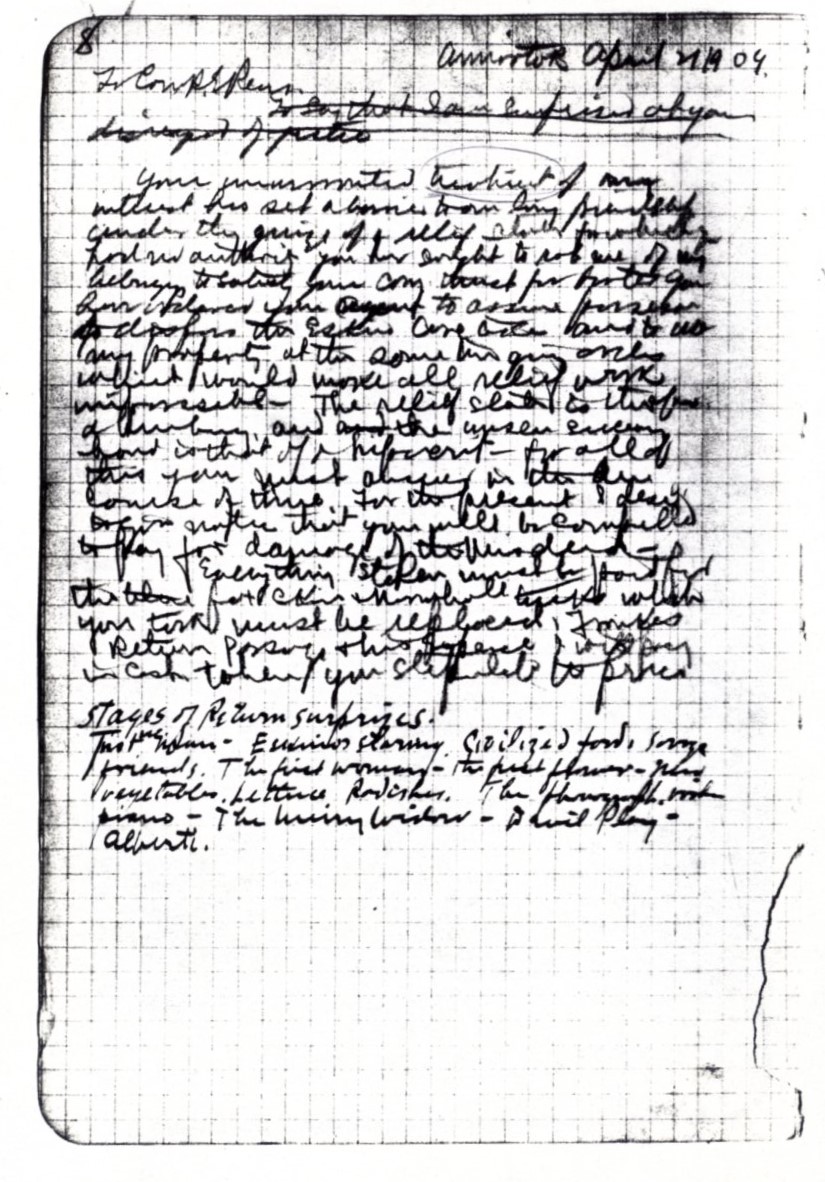

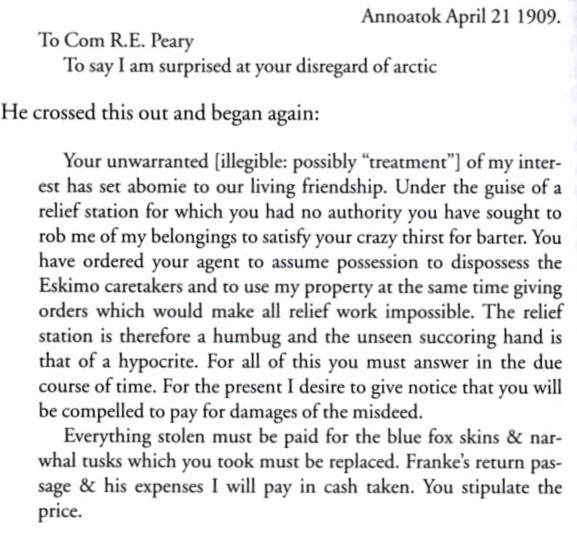

Cook then took an interest in Peary’s instructions to Murphy, copying them out in full. He also began an indignant note to Peary expressing his outrage at Peary’s arrangements in regard to his property:

But he then thought the better of it and did not leave it for Peary. But he realized he must now beat Peary to the punch and be the first to put in his claim, even though Peary could not possibly have reached the Pole before he claimed to have reached it. He hurriedly packed up and left Annoatok on April 21.

Despite his injunction to his Inuit companions, Cook expresses no surprise that when he reached Neurke, the first Inuit village as he started on his 800 mile sledge journey to reach the Danish settlements down the coast, that the word was already out:

Meanwhile, third parties with no connection with either Cook or Peary heard from natives particulars of Cook’s journey.

The indignant note is among the Frederick A. Cook papers at the Library of Congress. The hand-written draft of Cook’s telegraphic report that he left with Kraul is now at the Royal Danish Library in Copenhagen. A transcription of this draft, which differs in some respects from what Cook telegraphed to the Herald, can be found in the author’s book, The Lost Polar Notebook of Dr. Frederick A. Cook.

Filed in: Uncategorized.