The Cook-Peary files: The “Eskimo Testimony”: Part 9: Analyses of the “Eskimo Testimony”: Dr. Cook’s

Written on June 20, 2023

This is the latest in a series of posts that publish for the first time significant documents related to the Polar Controversy.

We have now come to the end of the accounts of what the Inuit said of Dr. Cook’s journey by all contemporary witnesses of relevance. The next task will be to sift through the various versions, note the contradictions they contain, and try to come to some decision on what value should be given to the “Eskimo Testimony” as verification or refutation of Cook’s claims. But before we do, let us examine the analyses done by others to see how they hold up. Not surprisingly, the first to raise doubts about it’s value was Frederick Cook. Of course, he was a very interested party, because if Peary’s version of what the Inuit said was true, his story of reaching the North Pole was irrefutably untrue.

We have already seen (in Part 3 of this series) Cook’s initial response to the statement and map published by the Peary Arctic Club purporting to show his actual route that it said was provided by Etukishuk and Ahwelah when they were questioned at Etah in August 1909. When Rasmussen’s second version of the “Eskimo Testimony” appeared (see the previous post), Cook had only just returned to America from London, where he had been living incognito for some months.

One of his first public statements when he returned, after an absence of more than a year, was a response to Rasmussen, which he sent in writing to the New York Times, which published it on December 26, 1910.

In it Cook analyzed the Dane’s statement and speculated on his motives for first enthusiastically supporting him in his first version of what he had heard in Greenland (see Part 7 of this series), and then publishing this new version, which was, in almost all important aspects, a total refutation of his first version:

“One cannot help but ask the question: Why did Rasmussen first launch out into this polar controversy and defend me, later to discredit me and then to champion Peary, and again later to pull down Peary? What is the point aimed at?”

Cook then went on to point out Rasmussen’s opening statement that “Already in 1909 there existed grave doubts as to whether Dr. Cook really had reached the pole” contradicted his previous wholehearted and enthusiastic support based on what he heard about Cook’s trip from Inuit he had encountered in Greenland at that very time, at the end of which he had declared baldly, “Briefly: It was the Eskimos’ opinion that Cook has been at the Pole, and that he, according to the statement of his companions, during the whole journey had shown unusual strength and energy.” Rasmussen made no mention whatever of any “grave doubts,” either by the Inuit or even himself. Cook speculated that perhaps Rasmussen held a grudge against him because John Bradley had forbid him to eat dinner with him aboard the Bradley, after Dr. Cook had invited him to do so, because of the way the Dane smelled in his oily fur clothing.

Cook then went on to point out that Rasmussen’s second version contained a number of “false statements.” Cook countered these by stating that he started with 11 sledges, not 9; in response to Rasmussen’s claim that they slept only once before reaching Ellesmere Land, Cook contended that they “had slept several nights before reaching Flagler.” The report’s contention that on the 19th day they changed their course westward, was not true, Cook said, because that would have necessitated “crossing the impossible, snow-free mountains of Heiberg Island”; and finally, that if, as Rasmussen had the Inuit say, “We stopped at open water near land,” Cook contended, “if so, the returning Eskimos would have reported it. The nearest water to land was at the big lead 100 miles off, where land was but a blue haze on the horizon.” Any of these incorrect statements could have been corrected by asking men who had traveled with him before they turned back for home, Cook said, and the first two could be corroborated by Rudolph Franke, who was with Cook as far as his first camp in Flagler Bay. “Even Mr. Peary’s statements contradict these assertions,” Cook declared.

Cook then stated, as he would do later in My Attainment of the Pole, that he used mirage and low banks of clouds to encourage in the Inuit the belief that they were always near land. Otherwise, he said, Inuit out of sight of land tended to panic and talk of desertion. And, of course, he contended that on March 30 they saw actual land to the west, but it was not “Ringnes Land,” as Rasmussen had the Eskimos say, but the new land, Bradley Land, that he had discovered.

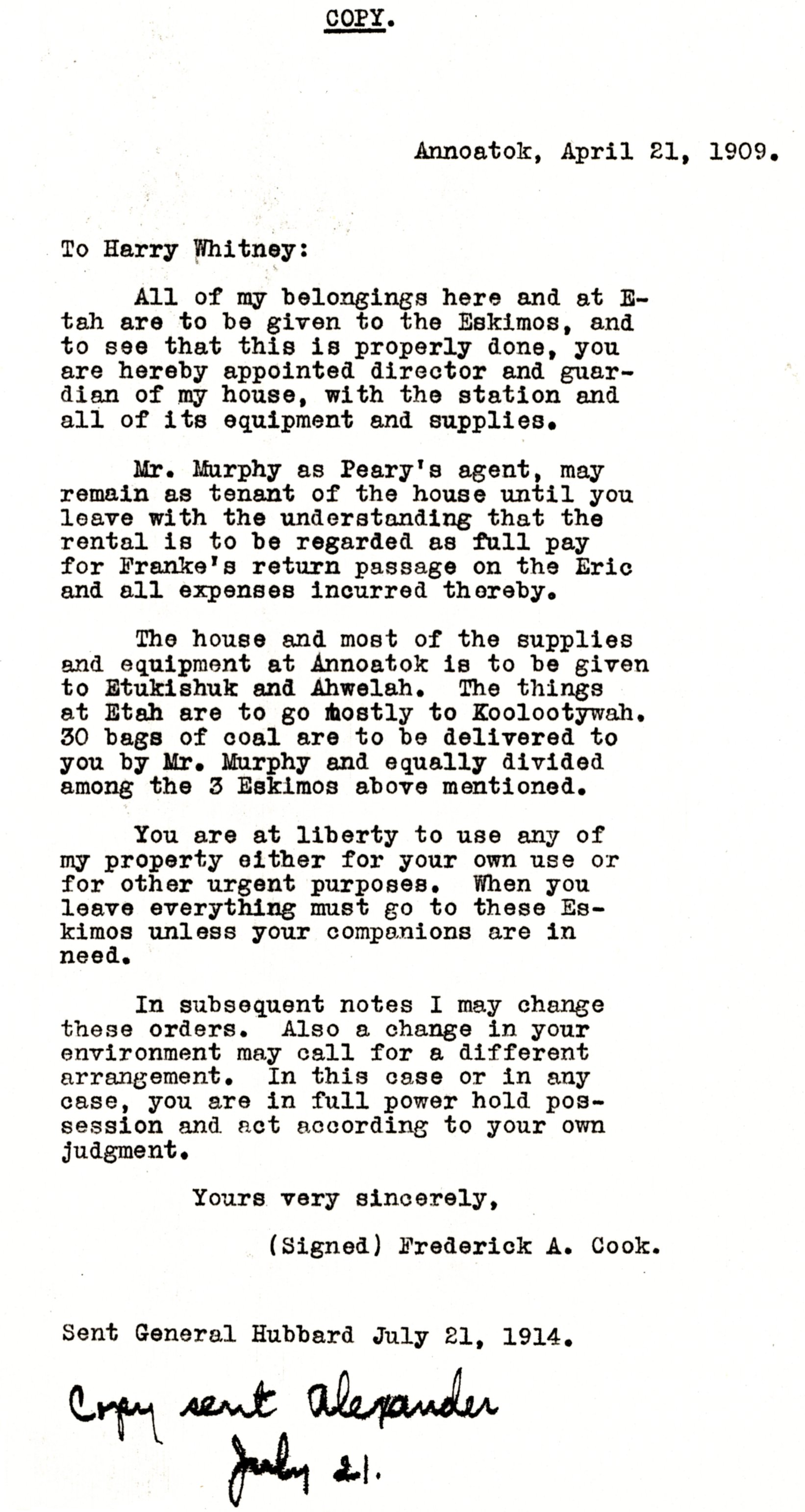

Cook also denied that he had cheated his Eskimos, calling this charge Rasmussen’s “meanest slur.” Cook said he had instructed Whitney before starting south to turn over all of his property left at Annoatok to the two men when he left, and Whitney could verify this, if someone would just ask him.

Cook then questioned the ability of the missionaries, from whom Rasmussen allegedly got the information contained in his second, anti-Cook version, to communicate efficiently with his Inuit companions. “In August of 1908 the steamer Godthaab arrives with the mission equipment aboard. Two half-breed Eskimo Christians were aboard. They spoke Eskimo perfectly, as they thought, and came with the laudable purpose of preaching God’ s Word.” But Cook had it from Captain Schoubye, he said, that this was not so. They spoke Danish well, but had not mastered the Inuit dialect spoken by the Polar Inuit living north of the Danish settlements. “The missionaries claiming to speak the native tongue could not make themselves understood. Yet these same missionaries are credited with sufficient intelligence to cross-question the Eskimo boys about something which they themselves do not understand.”

This might seem a remarkable statement, but according to Kenn Harper, who speaks a number of Inuit dialects, Inuktitut, the one spoken by the Polar Inuit, is the most difficult to grasp. “Knowing other Eskimo dialects doesn’t help a lot when trying to learn Polar Eskimo. I lived among the Polar Eskimos for two years . . . after living among Canadian Eskimos for many years. . . . Yet I found their language very difficult to learn. I had assumed that this was a problem unique to a white man speaking any Eskimo dialect as a second language [but] . . . an old Eskimo man that I was visiting told me that, even though he was been to Qaanaaq a few times, and has received visitors from there many times, he still finds their language hard to understand.” (letter from Harper to the author, dated October 10, 1994, possession of the author).

In the end, Cook concluded, “the only rational explanation for Rasmussen’s irrational course is to credit him with an ambition to get int o the limelight . . . But need an explorer stoop to the depths of a literary muck-raker to get public attention?” Although this last statement proved most ironic in light of the content of My Attainment of the Pole (MAP), published a year later, is there any validity to Cook’s arguments?

How many sledges Cook had at the start of his polar attempt is a trivial detail of no consequence. In MAP he said he had 11, and in Franke’s published narrative he also said 11, and it appears from a photographic copy of his original field diary recovered by the author in 1993 in a Copenhagen library, that he had either 11 or 10, not 9, so he is correct on that. The diary names the eight Inuit who accompanied him and Franke, so 10 sledges would be more logical, one to each man.

The second “false statement” Cook cites is actually not false, however. Cook’s party spent one night on the ice between leaving Annoatok and reaching Pim Island, a small island just off the eastern coast of Ellesmere Island, so Rasmussen was correct on that detail. But Cook’s counter-statement that they slept “several nights before reaching Flagler,” is equally true. According to Cook’s field diary it took them four days to reach Flagler Bay, which is also on the coast of Ellesmere Island.

On the 19th day out, according to Cook’s diary, the party was in camp in Sverdrup Pass, held up there by a glacier that blocked his route to Bay Fjord, though in MAP he was already on his way up Eureka Sound on his way to Cape Thomas Hubbard on that day. In the first case he was headed west already, and, in the version in MAP, he did not take a westerly course until heading northwest after he left land and started across the Arctic Ocean. In the MAP version, Cook’s statement that if had he turned west on the 19th day he would have had to cross the mountains of Axel Heiberg Island would be true. But there may be another telling possibility for the use of the terms 18th and 19th day in Rasmussen’s statement.

The only account Cook had published of his journey at the time of Rasmussen’s 1910 statement was the serial account that had been published in the New York Herald in September-October 1909. In it he reported that he had left Cape Thomas Hubbard on March 18 and that his supporting party of two additional Inuit had turned back three days out on the ice, or March 21th. Peary’s 1909 statement had him abandoning his polar quest the day after he left land, or March 19th. Perhaps the days given are actually a reflection of these dates, not the number of days on the trail, because even in Cook’s published version, he took far more than 18 days to reach his jumping off point. This would show that perhaps Cook’s published report and Peary’s published statement were used to concoct the “missionaries’” story, because, if that is so, that is something the Inuit could not have done independently.

That the Inuit said they were stopped by open water a short distance from land is the most important of the alleged “false-statements,” because it implies that Cook gave up almost as soon as his real journey toward the North Pole had begun, just as Peary’s statement had alleged. But, as we have seen (see Part 4 of this series) Borup’s notes show that the two additional Inuit did indeed accompany Cook more than one day north of land before returning. Of course, just how far Cook went out on the Arctic Ocean is still a matter of debate once the two turned for shore. The distance Cook actually went will probably never be known with certainty, as we shall see later. But Cook’s statement that “The nearest water to land was at the big lead 100 miles off, where land was but a blue haze on the horizon” is of great interest in this connection.

Of course Rasmussen’s “meanest slur” is demonstrably false. Cook instructed Whitney to distribute his goods to his two companions, just as he said. A typewritten copy of these instructions can now be found in Peary’s papers at NARA II.

So, on the whole, all of Cook’s objections to Rasmussen’s statement hold up pretty well, based on his published account. Even so, there are other reasons why Rasmussen should not have regarded the missionaries’ report to him “as absolutely authentic,” if only because the report’s contents are, themselves, self-contradictory, and, as Cook pointed out, some of it is directly contradicted by Peary’s 1909 published statement attributed to the same two Inuit, which Peary also contended was “absolutely true.”

Let us consider some of the statements from the missionaries’ report:

• “It took four days to cross Ellesmere.” According to Dr. Cook’s field diary, it took 18 days to cross Ellesmere Island from the head of Flagler Fjord to Bay Fjord. In Cook’s version in MAP, he intentionally compressed his journey to Cape Thomas Hubbard so that in his eventual account of his polar attainment he would have arrived at land’s end with a plausible amount of time left to reach the pole and return before the ice went out. So, in MAP he reported it only took him 5 days to cross the island. So, again, this detail could also have been derived from Cook’s published statements, but it is contradicted by what actually happened, as recorded in his field diary. Had the statement been from the Inuit’s actual experience, they would have indicated a number of days closer to 18 than to 4.

• “18 days out our companions left us. We then had gone only about 12 English miles from land.” This is absurd on its face. Even in Dr. Cook’s Herald serial he claimed he had taken from February 19 to March 18 to reach Cape Thomas Hubbard, a span of 29 days (1908 was a leap year). In actuality, according to his field diary, he took much longer: from February 26 to about April 2, so about 36 days. There can be no doubt about what day “our companions left us”; that was when Inughito and Koolootingwah turned back three days out on the ice. In MAP that would have been March 21; in the field diary it would have been approximately April 5. There is documentary evidence from Harry Whitney and others who spent time with the Polar Inuit that, while they could draw a fairly accurate map of coastlines they were familiar with, they had no concept of distance traveled, and had no means of estimating it. They certainly did not think in terms of “English miles.” Journeys to them were measured in “sleeps,” meaning days of travel, not measurements of distance. Curiously, 12 miles is the exact distance later assigned to Cook’s turn back point by Donald MacMillan in 1914, but he assigned other distances in other writings.

• “The ice was fine and there was no reason to stop, for anyone who wanted to go on could do so.” Yet later in the report it says “on the way we stopped at open water near the land.”

• “On the 19th day (or the day after their companions left them) Dr. Cook took observations with an instrument he held in his hand, and we changed course to the West.” It was a major point of the 1909 campaign against the validity of Cook’s claim that he was incapable of making accurate astronomical observations with a sextant. The whole point of the Dunkle-Loose affidavits was to show that’s why he hired them: to provide him with a competent set of fake ones to convince the scientists at Copenhagen. If they provided these, however, Cook did not submit them in proof of his claim, but because he submitted NO observations at all, this led to his claim’s rejection by the Konsistorium appointed to examine his “proofs.” Yet here his two companions allege he took observations “with an instrument he held in his hand,” implying a sextant. Of course, he could have just made a show of making observations as an excuse to change course. The Inuit had no understanding of “observations” or how a sextant would be properly used, let alone in which direction the North Pole lay, for that matter, so this statement is not significant.

• “We left a lot of food for men and dogs and [Etukishuk] went ahead to examine the ice. He reported it in good shape, which it was, but Dr. Cook looked at it and said it was bad.” Cook never claimed to have left any caches of food on the polar pack ice. To do so would have been futile, because any such caches would have just drifted away with the ever-moving ice, never to be located again. He did leave a cache at Cape Thomas Hubbard, however, before departing land. This cache was referred to in both Cook’s Herald serial as well as Peary’s statement. This statement also implies that it was Cook who refused to go on, even though the ice was “in good shape.” It’s a historical fact that explorers who traveled with Inuit found them extremely reluctant to venture far onto the Arctic pack ice. Some on Peary’s 1906 expedition even feigned illness to excuse themselves from going on, and Peary punished them by making them walk all the way back to his ship, frozen in at Cape Sheridan, without supplies. According to his field diary, on MacMillan’s trip toward “Crocker Land,” his two Inuit, one of whom was Etukishuk, begged him to return “as Dr. Cook had” several times on their journey across the ice from Cape Thomas Hubbard. Therefore, it is hardly credible to imply that Etukishuk tried to persuade Cook to go on when he judged the ice “in good shape” but Cook “said it was bad.” The Inuit would have been delighted to return as soon as possible, get off the treacherous moving pack ice, and claim their rewards.

• “We stopped one day and went over to Ringnes Island before the snow had melted (April). We had not had the least fog on the ice. At this time the sun was just below the horizon at night. It was the month when it does not get dark (March). Later when near Axel Heiberg Land, we passed two days in a fog.” The mention of fog is another indication that Cook’s published story in the Herald may have been consulted before Rasmussen’s anti-Cook account was written, because Cook mentions there that on his return from the pole he was unable to get his bearings for about 20 days because of constant fog. Peary’s statement makes no mention of fog. Additionally, this paragraph is an astronomical and geographical muddle. First, it says it was “April” when they went over to Ringnes Island, and at this time the sun was just below the horizon. At the latitude of Amund Ringnes Island in April, the sun would have risen well clear of the horizon and would be visible continuously 24 hours a day. Then follows directly the statement that is was “March,” not April, and “later when near Axel Heiberg Land . . . ,” They had started from the northern tip of Axel Heiberg Island, which is far north of the Ringnes Islands, but Peary’s map does show them crossing over to the bottom of the island after leaving Amund Ringnes Island before crossing Norwegian Bay, so this is not as illogical as it might first sound. However, the lack of mention of going down the west coast of Axel Heiberg Island before going to Amund Ringnes is curious.

• The report contends that the Inuit knew Cook was a liar when he was seen drawing a map of his route far out to sea, where they knew they had never been. Again, this reminds one of MacMillan’s later claim (in 1914) that when he showed them Cook’s claimed route on the map in MAP, that his former companions “laughed” at it because they knew they had not been that far at sea. This is a strange coincidence, at the very least, and Edward Brooke, the cameraman on MacMillan’s 1914 expedition, said that when he questioned Etukishuk and Ahwelah while he was in Greenland that same year, that they said “they went far from land for a long time” (see the author’s Cook & Peary, page 566).

• Other than the references to Ringnes and Axel Heiberg Islands, there is little or no information about their return route until they reach Hell Gate, where the report says Dr. Cook instructed them to abandon their dogs. In MAP, the dogs were abandoned near Cape Vera after crossing Colin Archer Peninsula, after which Cook says he set out on to Jones Sound in the folding boat. He does record visiting Hell Gate, but only after one of the wildest tall tales in the book, that of being blown there in a fierce storm from out in Jones Sound while lashed aboard a floating iceberg. However, the report doesn’t mention this memorable adventure, but it does say “we do not know how many days we slept on this part of the trip.” So there are no clues even to the amount of time that passed, much less where they traveled or what they did. It seems strange that the same two Inuit who were alleged by Peary to have drawn the detailed map of their travels with Dr. Cook in 1909, had no such details to provide the missionaries in 1910.

• The missionaries’ report says that Dr. Cook told the Inuit “we will reach human beings (Baffin’s Land) within two days.” While it is true that Cook’s plan was to try to rendezvous with one of the Scottish whalers that visited Lancaster Sound each year as a shortcut home, it’s absurd to think he would have said he could travel from Hell Gate, on the extreme west end of Ellesmere Island, to Baffin Island, a distance of well over 350 miles in an airline, in two days. The report mentions that they mistook a distant rock for a tent, while searching for “human beings.” Arctic light does do odd things to distant objects. In MAP at about this same point, Cook says that they thought they saw two men in the distance, only to find on approaching them, that they were two ravens.

• The report goes on to say that after searching for human beings for a “long time” they came to an island where eider birds were nesting. On Peary’s map, the Inuit were alleged to have found nesting eider ducks near Cape Vera, which is near where Dr. Cook said he descended to Jones Sound from Wellington Channel, and he mentions securing eider ducks near there in MAP. Cape Vera is not far below Hell Gate across the water on the coast of Devon Island, a distance of around 60 miles along the coast, if they took the track outlined on Peary’s map. So if they actually followed that course, they would not have taken “a long time” to reach this point from Hell Gate. Moreover, the relevant passage in Peary’s statement says that after reaching Simmons Peninsula on Norwegian Bay “They spent a good deal of time in this region and finally abandoned their dogs and one sledge, took to their boat, crossed Hell’s Gate to North Kent, up into Norfolk Inlet, then back along the north coast of Colin Archer Peninsula to Cape Vera, where they obtained fresh eider duck eggs. Here they cut the remaining sledge down, that is, shortened it, as it was awkward to transport with the boat, and near here they killed a walrus.” Peary also gives a time frame for their arrival at Cape Vera: “The statement in regard to the fresh eider duck eggs permits the approximate determination of the date at the time as about the 1st of July (This statement also serves, if indeed anything more than the inherent straightforwardness and detail of their narrative were needed, to substantiate the accuracy and truthfulness of the boys’ statement. This locality of Cape Vera is mentioned in Sverdrup’s narrative as the place where during his stay in that region he obtained eider ducks’ eggs.” The time frame is close to Dr. Cook’s story in MAP: he says he was near Cape Vera on July 7. So if it were truly April when they were at Amund Ringnes Island, it took them more than two months to get from there to Cape Vera. Why is there no mention in either Rasmussen’s, or for that matter, Peary’s statement as to what they did during these two-plus months? It does not square with the detail described on other portions of their alleged route.

• Rasmussen’s report then says “We followed the land past Cape Sparbo, and when our provisions were nearly gone, we returned toward Cape Sedden, where we arranged for wintering.” Again, this is geographically absurd. They did go past Cape Sparbo, but turned back when they had reached the bay just beyond Belcher Point. They wintered at Cape Sparbo, not Cape Seddon, which is on the west coast of Greenland, far across the open waters of Baffin Bay, which they would have been incapable of crossing in their small collapsible skin boat. In MAP, Cook says they turned back just beyond Belcher Point.

• The description of their wintering contradicts Cook’s dramatic tale of spending a “Stone Age Winter” in an “underground den,” but it is much closer to the truth. They had plenty of ammunition, killed the abundant game at Cape Sparbo at will, and were comfortably sheltered in a turf and stone igloo for the winter. Cook’s diary that he kept over that winter confirms all this, no matter what he later wrote in MAP. How they spent the winter, the Inuit making clothing and Cook writing constantly, is also accurate, as is the description of their journey back to Annoatok, as far as it goes. When they arrived there in April 1909, however, they were near starvation. That’s why they abandoned their sledge, in a desperate attempt to reach Annoatok after being diverted far to the north by open water in their attempt to cross over to Greenland from Pim Island.

• As noted above, Cook did not cheat his Eskimos. It was Peary who did so. He countermanded Cook’s instructions, which he had in his possession, since a copy of them is now among his papers at NARA II, and instructed his men to give nothing to any Inuit who helped Cook, but to distribute the excess supplies to those who had aided him instead.

In summary, there are several suspicious points that suggest that whoever wrote the “missionaries’” report had consulted Cook’s New York Herald serial and Peary’s 1909 published statement before doing so. The report is chronologically questionable and a geographical muddle in several places, making several of its statements impossibilities. The report is also in contradiction of several points made in Peary’s 1909 statement attributed to the same two Inuit who are said to be the source of missionaries’ statement, and prefigures later statements about Cook’s journey not in Peary’s account, but made by Donald MacMillian only in 1914, suggesting, perhaps that MacMillan’s account took into account Rasmussen’s 1910 statement. So, on all these points, their report cannot be “absolutely authentic” without disqualifying Peary’s. On the other hand, Cook’s stated objections to it are all at least consistent with his previous account published in the New York Herald in 1909 and as later elaborated in MAP, though a number of them are refuted by the contents of Cook’s original field diary recovered by the author. However, Rasmussen’s statement is more accurate than Cook’s version of the events of his overwintering at Cape Sparbo. In this, at least, the statement is, indeed, “absolutely authentic.”

But Dr. Cook was not the last to take up the questions posed by the various accounts of the “Eskimo Testimony.” It would become the subject of detailed analysis by several students of the subject over the next 100 years, some trying to discredit Cook, others trying to vindicate him.

Filed in: Uncategorized.