The Cook-Peary files: The “Eskimo Testimony”: Part 10: Analyses of the “Eskimo Testimony”: Has the North Pole Been Discovered?, Volume 1

Written on July 6, 2023

This is the latest in a series of posts that publish for the first time significant documents related to the Polar Controversy.

In the wake of the polar controversy, early on, those who followed it closely noticed inconsistencies and impossibilities that led several of them to publish studies aimed at showing there was room to doubt anyone had yet reached the North Pole. As early as 1911 a small book appeared in England by W. Henry Lewin entitled Did Peary Reach the Pole? The topic became a life-long interest of Lewin’s, who often published anti-Peary arguments in his private intellectual journal, The Individualist. He later gathered this material together as The Great North Pole Fraud in 1935. In all of these writings, Lewin never uttered the name of Cook, it only appearing in them if someone else was quoted as uttering it. Clearly, to Lewin, Cook was beneath contempt, and his claims beneath consideration.

Even Ernest C. Rost’s anti-Cook speech published under the name of Representative Henry Helgesen, in the Appendix to the Congressional Record for September 4, 1916, which attempted to dismember Cook’s claim through comparative analysis of his own various writings and those of others, did not devote any space to any account of the “Eskimo Testimony” from any source. Having already blasted Peary’s credibility in several devastating “Extension of Remarks” speeches Rost/Helgesen could hardly bring his “evidence” against Cook to bear.

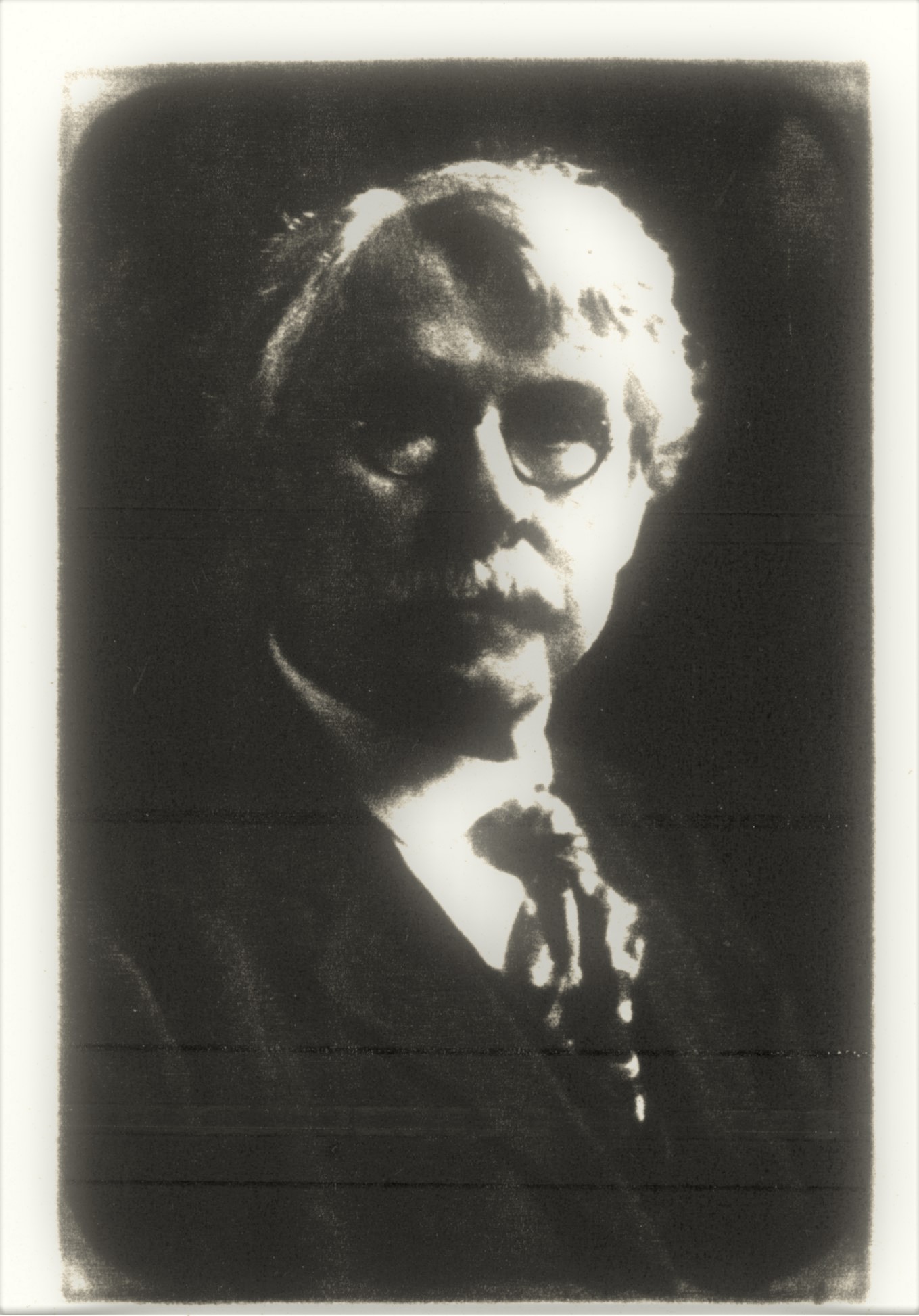

Captain Hall

The only one to take the topic up was Thomas F. Hall, a former sea captain and president of the Hall Distributor Co. of Omaha, Nebraska, a manufacturer of feed grain equipment.

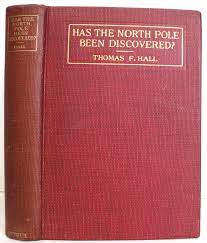

His remarkably exhaustive study, Has the North Pole Been Discovered?, purported to be an impartial analysis of both Peary’s and Cook’s claims.

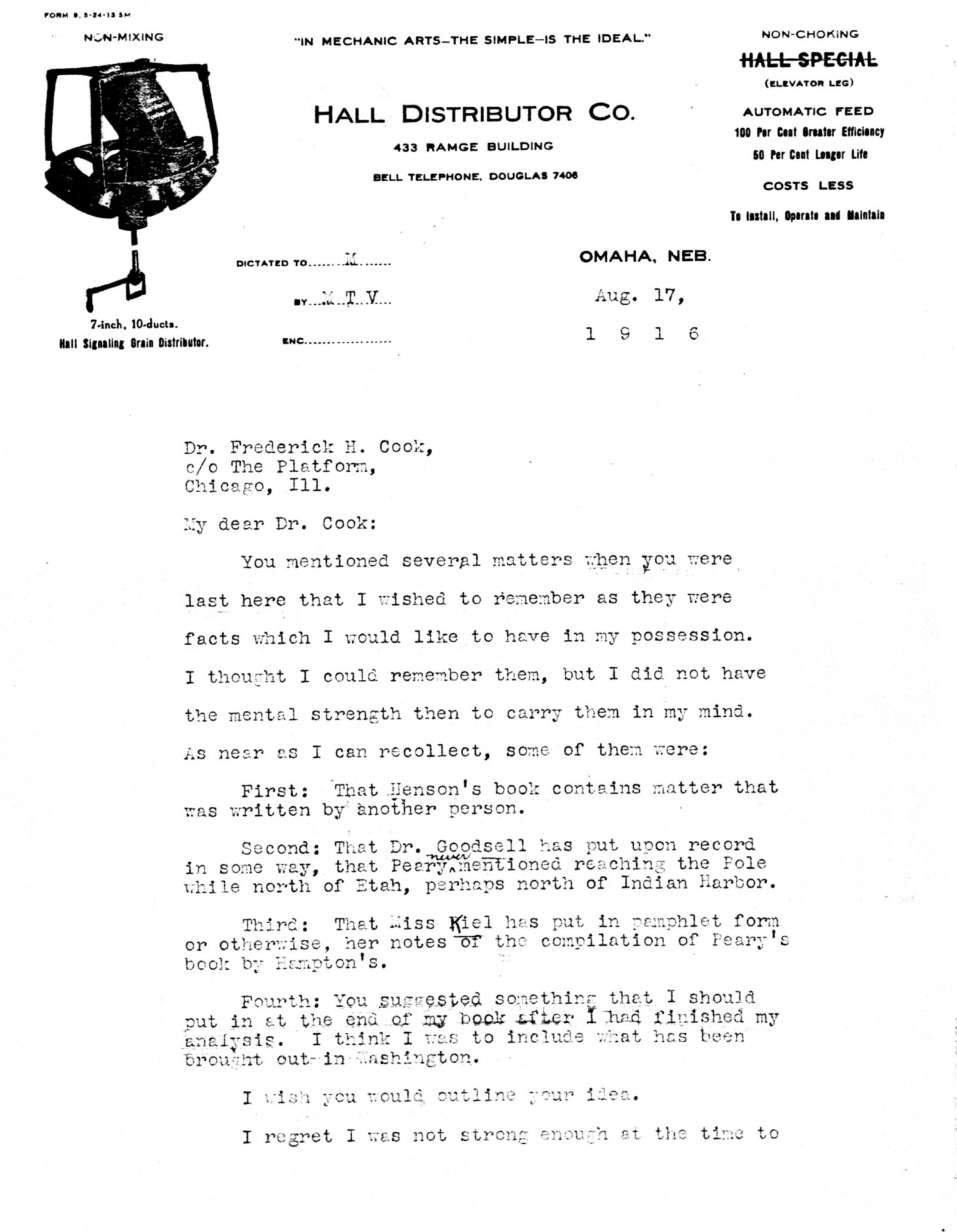

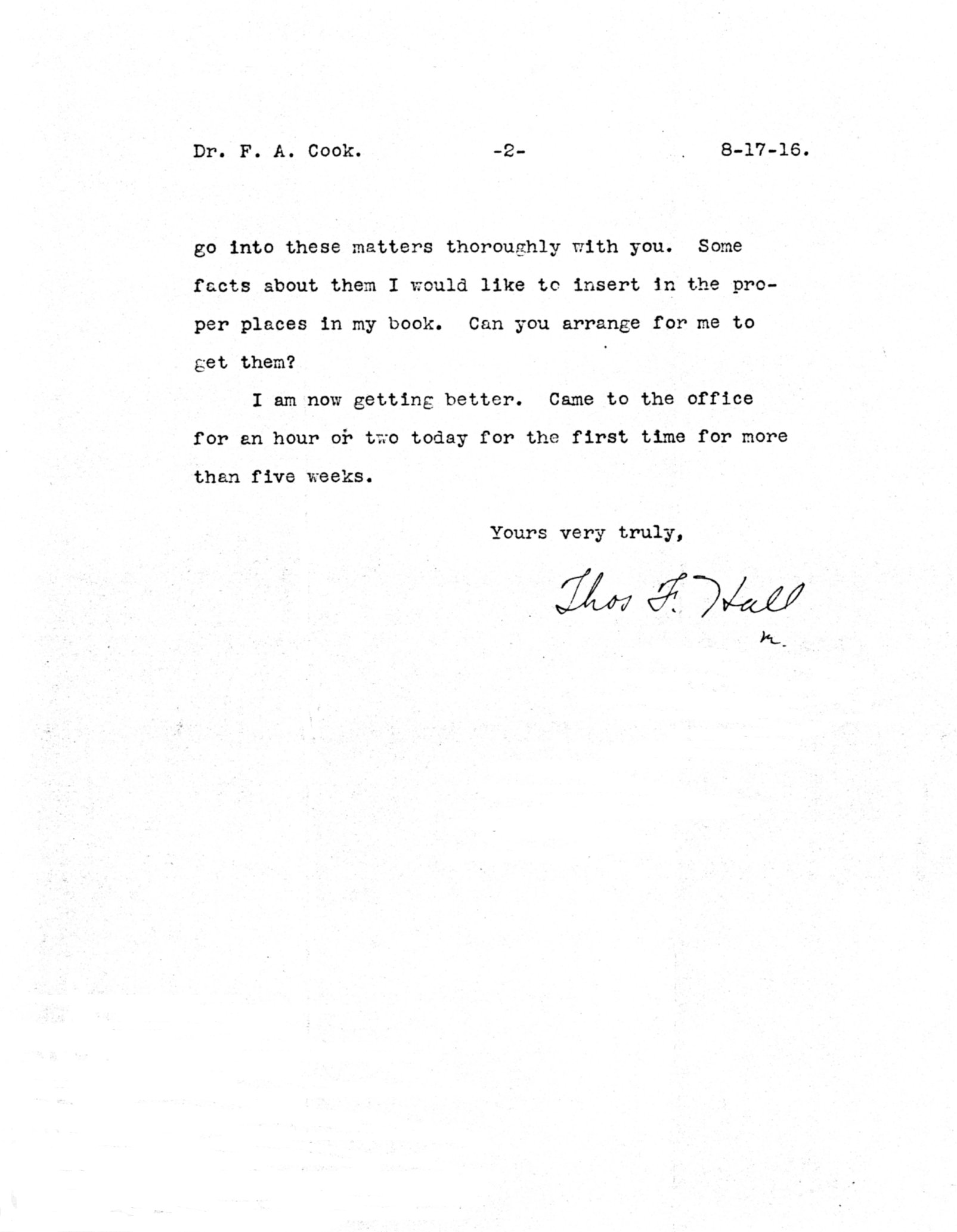

However, anyone who reads Hall’s entire book will not believe that it was impartial. Clearly, Hall favored Cook, if only because establishing Cook’s priority at the North Pole would deprive Peary of the honor, because Hall’s obvious loathing of Peary was at the heart of his obsession with the Polar Controversy. In fact, Hall had contributed material used by Rost in his speeches against Peary, and, as shown by this letter now in the Cook Papers at the Library of Congress, personally met with Cook and solicited material from him to include in his book before it was published.

Hall takes up the “Eskimo Testimony” in his chapter entitled “How Peary Discredited Cook.” For anyone but a devotee of the subject, Has the North Pole been Discovered? is a laborious read, with it’s numerous rhetorical questions, repetitive digressions and involved theoretical suppositions. But for those willing to wade through its acres of rhetoric, it does contain a number of salient points on the topic at hand.

Hall takes up the “Eskimo Testimony” in his chapter entitled “How Peary Discredited Cook.” For anyone but a devotee of the subject, Has the North Pole been Discovered? is a laborious read, with it’s numerous rhetorical questions, repetitive digressions and involved theoretical suppositions. But for those willing to wade through its acres of rhetoric, it does contain a number of salient points on the topic at hand.

Hall points out the peculiarities of Peary’s “proof” against Cook, which ultimately undermined its force as “evidence” and explains it’s failure to impress either the Press or the Public. For instance, although various trivial questions were recorded as specifically posed to the Inuit, all of which were designed to elicit answers that would imply that Cook never traveled very far north of Cape Thomas Hubbard, the supreme question, “Did you go to the North Pole?” was apparently not asked. Hall contends that the question was asked, but because Peary already knew the answer he refrained from giving it; as he said at Sydney, “I heard at Etah . . .” before clamming up. But the rest of his sentence was finished by Henson, who said in his World interview, “[Dr. Cook] ordered [his Inuit] to say that they had been at the North Pole, [but] after I questioned them over and over again they confessed that they had not gone beyond the land ice.”

While these questions about dogs, killing game on the ice, and the amount of supplies they had upon return were meant to imply Cook could not have made the epic journey he claimed, Peary’s “proof” was very indefinite about just how far north they had actually gone, its most concrete statement being that the Inuit said they were never out of sight of land, without giving any specific estimate of distance, though Henson thought it was no more than 25 miles. Hall attributes this evasiveness to the fact that the published “Eskimo testimony” conflicted with Peary’s earlier statements about the extent of Cook’s journey north. First, he had wired that “his Eskimos say he did not go far from land.” A second telegram gave the distance as “two sleeps from land,” or the indefinite distance covered in two days of travel. Another further refined this to “two sleeps from Heiberg Land.” However, Hall deduces, once Peary had reached Battle Harbour and had had the opportunity to read Cook’s first published account as wired from Lerwick, he found these earliest statements contradicted by Cook’s account, which would ordinarily be unimportant had Cook not had two witnesses in the form of his support party of Koolootingwah and Inughito, who had left him after THREE days travel from land. So when the statement was eventually released after a delay of more than a month, and in that time had passed through the hands of several members of the Peary Arctic Club before being so issued, it said that Cook had gone one more march to the northwest the day after his supporting party left him, or by Cook’s account, FOUR days out on the ice. What’s more, Peary knew this to be true even when he sent the earlier telegrams, because MacMillan’s notes on the interviews include Inughito’s statement that they had gone with Cook three days north before turning back without sleeping at the third camp (see Part 3 of this series). Obviously, Peary, wishing to minimize Cook’s northern journey, however, had suppressed this knowledge.

The Peary Arctic Club’s version, rather than making a clear statement one way or the other, tries to obscure these conflicts. It does not actually say that Cook went four days away from land. What it does say is that he went one day beyond the camp where the support party turned back, but never makes clear just how many days were involved in getting to that point. Hall surmises, not without logic, that this obfuscation was the result of Peary’s original statement, which he handed to General Hubbard on the train platform in Portland, having been rewritten by members of the Peary Arctic Club. Many of them, like General Hubbard, were lawyers, and the final statement was an attempt to cover these conflicts and to present a technically true statement that, while it could not be refuted by witnesses, did not say outright what Peary’s original statement may have said, and especially, did not mention what Cook’s two Inuits’ answered to the ultimate question that they surely must have been asked: “Have you been to the Pole?” Hall, always ready to give Cook the benefit of the doubt where he denied it to Peary, therefore concluded that Cook then must have gone at least 92 miles away from land, since this is the distance Cook records as being covered in his first four days of travel in his “field notes” at the end of My Attainment of the Pole.

Although Hall spends considerable time trying to answer the question of, if not the North Pole, where Cook might have been between the time his support party left him and he went into winter quarters at Cape Sparbo, which fact was not questioned even in Peary’s statement. However, he does not take up in any detail Peary’s alleged route for him as shown on the explicit map that accompanied the Peary Arctic Club’s obfuscacious printed statement. To Hall, the only element of it even touched on implicitly, or worth considering, was why would Cook, if not in extremis, as he claimed, have taken such a route as he claimed to have taken, or even the one the Inuit were alleged to have drawn on Peary’s map when, if he returned to land after only a short trip north on the Arctic Ocean, the way was then open to him to merely return along his outward route and reach civilization to enjoy the glory and gain he would realize from a false claim a year before Peary could possibly return and put in his own claim, true or false.

Therefore, Hall does not consider any of the significant points that might be made by a comparison of the route shown on the Peary map to that claimed by Cook, with the idea of establishing which is the more plausible and, if the Eskimo Map wins out, what distance that goes toward answering Hall’s question about where Cook had been, if not the North Pole. Although Hall missed this opportunity, we shall attempt to take up consideration of these points at the end of this series of articles.

But Has the North Pole been Discovered? was not Hall’s last word on the subject. In 1920 he published a supplement to the book which attempted to account for developments since it’s publication. In it he devoted 52 of its 62 pages to subjects related to the “Eskimo Testimony.”

Captain Hall’s photograph is in the photograph division of the Library of Congress.

Filed in: Uncategorized.