The Cook-Peary files: The “Eskimo Testimony”: Part 11: Analysis of the “Eskimo Testimony”: Has the North Pole Been Discovered?; Volume 2

Written on August 26, 2023

This is the latest in a series of posts that publish for the first time significant documents related to the Polar Controversy.

The publication of Hall’s monumental study of the Polar Controversy in 1917, although flawed by his severe animus against Peary, was a turning point in the history of this long-lasting geographical dispute. But Hall was not willing to let the subject go, even then. In 1920 he published a 62-page paperbound supplement to it, which he styled “Volume II” of Has the North Pole been Discovered? Despite its slightness, which he termed on its title page a “review of allegations of facts, which have come to light since Volume I was printed,.” Hall claimed “these interesting allegations supply the links, which complete the chain of evidence, regarding the alleged testimony of Cook’s Eskimos.”

The book consisted of two chapters and an epilogue. The first was devoted to MacMillan’s article published in the February 1918 number of The American Geographical Review already referred to in Part 5 of this series. Hall noticed all of the discrepancies in MacMillan’s article and the statement allegedly made by Cook’s companions and published by the Peary Arctic Club in October 1909, which was signed by MacMillan and other members of Peary’s expedition, attesting that it was a true representation of the statements of Etukishook, Ahwelah and Etukishook’s father, Panikpa. After comparing that statement with that published in 1918, Hall concluded that it was impossible to reconcile the contradictions between the testimony of 1909 and that of 1918 as competent or consistent evidence.

The second chapter was concerned with an article entitled “Solving the Problem of the Arctic,” published by Vilhjalmur Stefansson in the October 1919 issue of Harper’s Magazine. Although he never stated it outright as his intent, the “problem” Stefansson apparently referred to was whether or not Frederick Cook actually went to the North Pole in 1908. Stefansson was always the master of innuendo when the facts were insufficient or in doubt. A reading of his vast papers at Dartmouth reveals many instances of his oblique techniques at insinuation and his indefatigable efforts to influence anyone interested in writing about the Polar Controversy, all the way into the mid-1960s, to minimize damage to Peary’s legacy and simultaneously to raise doubts about Cook’s truthfulness.

In 1919 Stefansson was only lately returned from the Canadian Arctic Expedition during which he traveled widely in the islands discovered by Sverdrup during the Second Fram Expedition of 1898-1902. On his expedition Stefansson discovered and mapped the few scraps of land Sverdrup had missed. The largest of these was an island he called “Second Land.” He placed the southwestern corner of this island at latitude 79º 50’ N and at longitude 101º 15’ W on a line between Cape Isachson on Ellef Ringnes Island and Cape Northwest on Axel Heiberg Island. He described the island as roughly pear shaped and about 800 feet high. This discovery of “the island which Doctor Cook did not see, although his plotted route as published in his book lies right across it,” Stefansson wrote in Harpers’, showed that “contrary to Doctor Cook’s observation, we found that the spot of latitude and longitude given by him did not show any moving sea ice nor any sea ice at all, and is instead near the center of the island which we have named ‘Second Land’.” As a result, he concluded that “there has been a good deal of cumulative evidence before. No single fact has been conclusive, but in the aggregate they have given a clear verdict. BUT HERE AT LAST WE HAVE AN INCONTROVERTIBLE PROOF.” Of what, Stefansson leaves the reader to decide, but the obvious inference is that Cook’s reports of his movements in My Attainment of the Pole were not factual, with the implication that his claim to have been to the North Pole was therefore equally false.

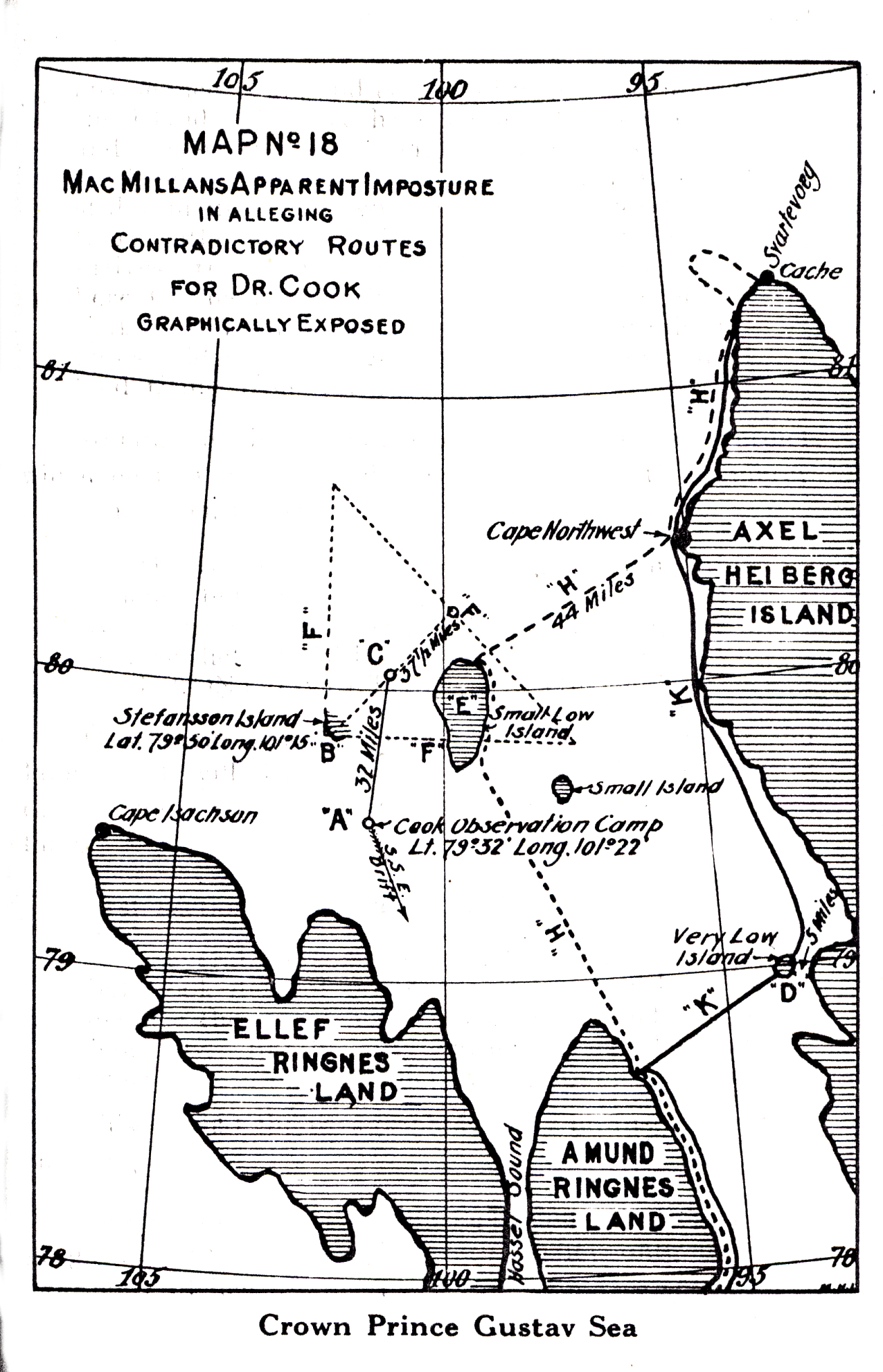

Hall goes on to demolish Stefansson’s innuendo by showing that the “spot of latitude and longitude given by [Cook]” (79º 32’ latitude, longitude 101º 22’) was not within 32 miles of the alleged location of “Second Land,” nor did his claimed route lie “right across it.” In much belabored prose and a diagrammatic map representing the various positions reported, he dismissed Stefansson’s claim of “incontrovertible proof,” as no proof of anything other than that Stefansson was willing to manipulate figures to support his ends of discrediting Cook’s polar claim, or at least his truthfulness in reporting the facts of his route.

Interestingly, in 1938, Stefansson, without saying so specifically, admitted that Hall was correct. He had planned as part of his book entitled Unsolved Mysteries of the Arctic to include a chapter entitled “The Problem of Meighen Island,” which was the name eventually given to “Second Land.” This article was suppressed because of fears of legal action threatened by Dr. Cook’s lawyers, but it was published privately in an edition of 300 copies by Stefansson in 1939. In it he states that his initial location of “Second Land” as reported in his article of 1919 was erroneous due to “a difference between longitude criteria which [Stefansson] used in the field and those later adopted for his maps by an official of the Canadian Government,” and as a result its location was actually farther East. As a result, in his typical oblique way, he attempted to correct his Harper’s Magazine account without removing the doubts he had put on Cook’s veracity by saying “Stefansson said in the magazine article it was strange Cook thought he was on moving ice when really he was on land. This should now be changed to read that it is strange Cook was able to look either trough or right past Meighen Island, with its dark westward cliffs facing him only ten or fifteen miles away, and see Heiberg Island fifty to eighty miles away without at the same time seeing Meighen.”

At the time he wrote in Harper’s, Stefansson claims he was not aware of the map that had appeared with Peary’s “Proof” in October 1909. He says this was only brought to his attention in July 1937 when he got a letter from Hugo Levin, an advocate of Cook claim, enclosing a clipping of a map from a Chicago paper in which it had appeared along with Peary’s 1909 account of the “Eskimo Testimony.” Frankly, I find this hard to believe. Stefansson was an ardent collector of all writings dealing with the Arctic and assembled a massive archive of polar related materials, now at Dartmouth College. To believe he had never seen a copy of the Peary Arctic Club statement with its accompanying map until nearly 30 years after it was published in hundreds of newspapers across the country seems incredible in light of this.

Of course, that map does show an island very near the size and shape of Meighen Island at exactly the location it now appears on modern maps—more accurately than Stefansson had placed it in 1916. And many has been the argument over how it appeared there 17 years before its official discovery. Hall wrongly assumes that it was already known from Sverdrup’s explorations, but Sverdrup missed Meighen Island along with its small northern companion, Perley Island, as well as the small islands scattered to the southwest of it, now known as the Fay Islands. Peary’s map not only placed Meighen Island accurately, but also mentioned the sighting of a second island at about the position of the Fay group. These facts strengthen the credibility of the Inuit’s alleged statement on that portion of Cook’s journey, but they have no bearing whatever on the truth of Cook’s claim to have reached the North Pole.

This is because Cook could have discovered Meighen Island either as the Inuit are alleged by Peary to have said—after a trip north of Cape Thomas Hubbard on which he never lost sight of land—or as Cook said, along the route he was compelled to take on his return after his attainment of the Pole due to an unknown westerly drift. Yet Cook denied as late as 1937 that he had ever seen Meighen Island at all. Since such a discovery would not have jeopardized his polar claim, if Cook did discover Meighen Island, why then would he not have reported it? After all, Sverdrup had left only a few scraps of new land in the Canadian Arctic undiscovered, Meighen Island being the largest of them. It would have been a feather in Cook’s cap to have discovered such significant new island, and would in fact have been his first such discovery.

We cannot know the answer to this question, but as I speculated in Cook and Peary, the Polar Controversy, resolved, Cook’s failure to report his discovery may have been due to his inability to take accurate navigational sights with a sextant. When such a new discovery is made, an explorer is expected to make such observations to fix its exact locality for future explorers and map makers. If Cook reported his discovery yet badly misplaced it, that would have grave negative implications for his ability to know when he had reached the North Pole, which at that time required careful celestial observations to verify his position on the featureless drifting ice of the Arctic Ocean.

On a map showing graphically the falsity of the claims about Cook made by Stefansson, Hall also drew in a route for Cook that he felt corresponded to MacMillan’s 1918 report, but was completely different from the one that appeared on the map allegedly drawn by the same two Inuit in 1909. Instead of traveling out to, and then down the western coast of Meighen Island, as they had shown there, MacMillan’s statement seemed to indicate that they had continued down the western coast of Axel Heiberg Island to Cape Levvel before crossing over to the east coast of Amund Ringnes Island. Off what appears to be Cape Levvel on Hall’s map, he places the “very low island” described in MacMillan’s 1918 text as lying at the 79th parallel. No such islands are shown on modern maps. However, Hall’s map is very sketchy and lacking in detail, being based on Sverdrup’s field maps. This small low island can’t be Meighen Island; it lies a full degree (60 nautical miles) farther north than the island sketched in by Hall on his diagrammatic map, and 25 miles across the Sverdrup Channel at its nearest point to Axel Heiberg Island, whereas MacMillan’s 1918 statement describes his island as only 5 miles from it. These facts minimize the chances of these inconsistencies between the two reports being typographical errors on MacMillan’s part.

Since whether or not Cook saw Meighen Island is irrelevant to Cook’s actual attainment of the Pole, Hall’s arguments about this point in both his chapters on MacMillan and Stefansson are not all that important. However, his main point in each chapter is that the stories allegedly attributed by MacMillan to the same Inuit witnesses in 1909 and 1918 have important irrevocable differences, and the manipulation of figures and the misplacement of Meighen Island by Stefansson invalidates his insinuations against the validity of Cook claim of polar attainment, weak at it was to begin with, on its face. As a result, Hall justly dismissed the various statements made by Cook’s Inuit as conflictual, and therefore without merit as evidence of the truth of the matter one way or the other. In Stefansson’s case, Hall rightfully recognized his 1919 article as a cunning attempt to undermine Cook’s credibility, which Stefansson continued to attempt to do in the suppressed chapter of his book and in his ongoing correspondence with any author who took up the matter for decades to come, despite his continual claims throughout as being one of fair-minded neutrality.

In the Epilogue to Volume II, Hall declared it would be the last he would write on the polar subjects, but he was not quite true to his word. In 1935 an essay dealing with the murder of Ross Marvin was included in W. Henry Lewin’s book, The Great North Pole Fraud, but it had no bearing on the present discussion. Hall used this epilogue to sum up his conclusions on the matter: “I have shown in this work that the stories of Peary and of others about Cook, are apparently impositions and forgeries, and I leave the evidence I have produced in proof of it, to be refuted, if anyone can do it. . . . Eliminating the alleged eskimo testimony eliminates the only charge ever made against Cook and leaves his claim undisputed.”

That of course did not prove to be the case. I’m sure Hall would be quite astonished to learn that, in the end, Cook’s claim to have been the first to attain the geographical north pole would be proved a fraud by documentary evidence from his own hand. Even though this has been the case, there will always be True Believers who can never be convinced, nor do they want to be for that matter. Their private fantasies about Frederick Cook are more important to them than Truth.

Filed in: Uncategorized.