The Cook-Peary files: The “Eskimo Testimony”: Part 12: Inuit Folk Memory

Written on September 14, 2023

This is the latest in a series of posts that publish for the first time significant documents related to the Polar Controversy.

There are four other miscellaneous accounts that do not fit into the narrative up to now, but I will now mention for the sake of completeness. The first is that of Paul Rainey, who in 1910 went with Harry Whitney aboard the icebreaker Beothic, captained by Bob Bartlett, on a supposed “hunting trip,” but many speculated that the game was Cook’s records Peary forced Whitney to cache at Etah. The Beothic party visited Etah, picked up Etukishuk there as a guide, then sailed to Cape Sparbo, where they inspected Cook’s winter igloo. Although Rainey said he wanted to avoid getting mixed up in the controversy between the two explorers, in an article he published subsequent to the voyage he volunteered that while on the Beothic Etukishuk had told him that Cook had never been out of sight of land or had ever seen “Bradley Land.”

The second was Mene Wallace’s, the Inuit Peary had brought to the US as a boy, then abandoned. He had been returned to Greenland in 1909. In 1910 he wrote to a friend: “I know you will expect something about Cook. Well, Dob, I have gone to the bottom of the matter. No one up here believes that Peary got much farther than when he left his party. His name up here is hated for his cruelty. Cook made a great trip North. He has nothing in the way of proofs here that I can find. I believe he went as near as anyone, but the pole has yet to be found. Cook is loved by all, and every Eskimo speaks well of him and hopes that he has the honor over Peary–has he?” Mene eventually returned to the US and announced he had “a big story about Cook and Peary,” and offered to sell it to the highest bidder. When asked if he had resolved the Polar Controversy, he said: “No, I don’t know who discovered the North Pole, I don’t know that it was ever discovered by anybody. What I know is what the Eskimos who accompanied Cook and Peary tell me. . . . I’ve been living with Ootah, Eginguah, Seegloo and Ooqueah, who were with Peary. They know just how many days passed during the journey. Wouldn’t it be interesting to compare their record with Admiral Peary’s proofs of his discovery? I’ve also talked with Etukishuk and Ahwelah, the men who accompanied Dr. Cook on his expedition in 1908.” Unfortunately, Mene found no takers for his “big story,” and died in the Spanish Flu pandemic in 1918 without ever telling more of what he “knew.”

The third of our miscellaneous witnesses is Edward Brooke, who was the motion picture cameraman who was on MacMillan’s Crocker Land Expedition. In 1915 he sent a letter to Senator Miles Poindexter, who was investigating Cook’s claim, saying that Cook’s two Inuit told him while he was in Greenland that “they went far from land for a long time.”

The last was also part of the Crocker Land Expedition. He was the expedition’s surgeon, Dr. Harrison Hunt. In his book, North to the Horizon, he quotes his diary for October 14, 1913: “We had a session last night with Etookashoo and Ahpelliah, the map of Sverdrup and [My Attainment of the Pole]. . . . Etookashoo agrees absolutely with Ahpellah as to the course they too, and resolutely denies that they were ever out of sight of land. Each of these two men traced the same course on the map, at different times, and without knowing the others had done so. . . .”They had no hardship whatever until nearly home. The picture that Dr. Cook claimed was taken at the North Pole was located by them on the map, near Ellesmere Land, some 400 miles from the Pole. . . The frank, open-faced manner with which these men answered our questions convinced us of the truth of their story. We tried in vain to break down their testimony but could not budge them.”

The last account by either of Cook’s two Inuit companions was given after Captain Hall’s last analysis was published. In 1932 Sargent Major Henry W. Stallworthy of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police mounted a search for the missing Krueger Expedition. He left Bache Peninsula on March 20 with Constable R.W. Hamilton, accompanied by seven Inuit, eight sleds, and 125 dogs. Splitting into two search parties once they crossed Ellesmere Island, Hamilton and four Inuit returned on May 7, after a 900-mile trip to Amund Ringnes and Cornwall Islands. Stallworthy, with three Inuit, traveled along Eureka Sound to the northern tip of Axel Heiberg Island, where he found a record indicating that Krueger was heading for Cape Sverre on the northern tip of Amund Ringnes Island.

Even though delayed by poor ice conditions and hampered by a shortage of food, Stallworthy completed his journey around Axel Heiberg Island and returned to Bache Peninsula on May 23, having covered 1400 miles. During his journey, he confirmed that Schei “Island” was a peninsula, just as Frederick Cook had said it was, and learned from his chief guide, Etukishook, that Dr. Cook had actually taken his photographs of the “North Pole” at about 82º North, within sight of land. Stallworthy’s party faced starvation on this journey and had to kill some sled dogs to survive. As Edward Shackleton later commented, Stallworthy “would be the first to admit, if it had not been for the skill of his Eskimos, he might never have returned.”

Both Etukishook and Ahwelah died in 1935, ending any possibility of further eyewitness accounts. However, the story of their journey with Dr. Cook in 1908-09 lived on in tribal memory.

In an appendix to his 1988 book, The Noose of Laurels, Wally Herbert published a substantial portion of a narrative drawn from folk memory by Inuutersuaq Ulloriaq. It had previously been published in full as “What has been heard about the first two North Pole Explorers” by the Greenland Society in 1984 in a Danish translation by Rolf Gilberg.

In his introduction to this appendix, Herbert wrote:

“What [Etukishuk and Ahwelah] told their own people is therefore the story that needs to be told, and I do not refer to the story given second-hand to Rasmussen which was published in the New York Times on October 21, 1909, but the story handed down by word of mouth among the polar Eskimos themselves. The oral tradition is the voice of their past and the Eskimos respect their past. Stories are always retold exactly as heard, not deviating by a single phrase or word, and one of the great exponents of that art of handing history on was my old friend Inuutersuaq Ulloriaq.”

Of course this is certainly not true. Folk memory is not an unchanging, stable thing; it depends upon both individual memory and the understanding by the hearer of what the last teller said. As it passes from one to the next it inevitably is altered, if only subtly, as it goes. Over long periods of time, it can even become Legend. Probably even such epics as the Odyssey are rooted in folk memory of real events, but can’t possibly be taken as literally true today. Each succeeding hearer adds or subtracts depending on his absorption and understanding of what he remembers of what he heard, and the temptation to embellish or alter a story for personal or cultural purposes is always present. So in examining the version of Cook’s journey as told by Ulloriaq, one need not accept it as not deviating by a single phrase or word.

Like all historical narrative accounts, comparison of its details with known facts establishes this beyond doubt. A few examples of this from Herbert’s appendix should suffice to prove this point:

• “As usual, Daagitkoorsuaq [Dr. Cook] went ahead on skis.” Dr. Cook took no skis on his 1908-09 attempt to reach the North Pole.

• “When they reached the northern tip of Axel Heiberg Land, the accompanying sledges turned around . . . only three people remained, and they spent many days at the northern tip of Axel Heiberg Land.” As we have seen, Inughito and Koolootingwah also remained with Cook, Etukishook and Ahwelah when the others returned. That the polar party could not have remained “many days” at the camp at the northern tip of Axel Heiberg Island is proven by the fact that these two additional Inuit, after traveling northwest with the others for three days, returned to land and were able to catch up with the seven that had initially turned back from Cook’s camp, overtaking them at the depot set up on Shei Peninsula on the outward journey, and from there the whole group took only until May 7 to return to Annoatok.

• “[Cook] had been along as doctor and ethnographer during [Peary’s] winter stay in Cape Cleveland 1881-2.” The expedition on which Cook was the doctor occurred in 1891-2.

• “They eventually reached the headland at Cape Sparbo in early September 1908. . . [Cook instructed them not to take too many Musk Oxen]. It was mid-summer. The meat had no suet which could be used to make tallow for fuel.” September is not “mid-summer” anywhere, especially in the Arctic.

• “Before very long the sun returned. They stayed put a long time as it was stormy for many days. But they knew the storms would stop when March came . . . . At the end of April 1909 the people of Anoritooq saw a small dot appear o the coast of Canada.” None of this matches Cook’s verifiable timetable. According to his autograph diary, Cook left Cape Sparbo on February 18, 1909 and arrived, according to witnesses, in Annoatok about April 15. Therefore, he left long before “March” and arrived in Annoatok long before “the end of April.”

• “They of course meant that they could see some of Cape Columbia and the north coast of Ellesmere Land the whole time. It was moreover the place which [Peary] used as a depot and starting point for his trips in 1907 and 1909, when he was on his may to the North Pole.” Peary was not in the Arctic at all in 1907, and he only used Cape Columbia as a depot in 1909. In 1906 he departed for the Pole from Cape Hecla.

• “Their leader said nothing to them about having reached the North Pole.,” yet later he says that while they were at Cape Sparbo, which they reached in September, they saw Cook’s map which made them decided “how much he had lied” about reaching the North Pole.

Another test of a narrative’s truth is its internal consistency. Ulloriaq’s account contains many self-contradictions. For instance, it says that before they left, the two Inuit “were very clear about the fact that the trip was to go to the North Pole, as Cook had shown them a map in Anoritooq and explained to them where it lay.” Yet he later says that Dr. Cook probably relied on his belief that “The two ignorant young men did not know where the North Pole lay,” and that “[Cook] never let the two young men . . . know anything of his lie about them reaching the North Pole. He was able to do this because they did not know where the North Pole lay, or so he thought then.” If he had shown them on the map where it was before leaving, how could this be? And this was after saying that “when summer eventually arrived . . .when [Cook] went out walking they saw a map in his papers, on which he had drawn a route all the way to the North Pole. The first time they saw it they had a good laugh because they knew there was no question of anything of the sort.” If they really had been shown a map before they left of where the Pole lay, they would have known they had not been to the Pole no matter what Cook had told them; if they hadn’t had this explained to them, then they would not know the route they “saw” on his map was “all the way to the North Pole.” Such variances with known facts and internal inconsistencies, put finished to the question of the infallibility of Inuit folk memory suggested by Herbert, at least in this case.

Kenn Harper specifically addressed this point in a paper delivered at Ohio State University in 1993. Harper had written an account of the tragic history of Minik Wallace, an Inuit, who as a boy had been brought to the United States by Peary. Harper who, himself, had married into the Polar Inuit community and lived there a number of years, vouched for the amazing fidelity of Inuit folk memory in many instances, but questioned Herbert’s insistence on absolute faith in it as reliably truthful to the point of “not deviating by a single phrase or word.”

“If this correct,” wrote Harper, “why would the ‘second-hand’ version told to Rasmussen [the one published in the New York Times on October 21, 1909, which Herbert specifically rejects (see Part 2 of this series)] differ in any way from the version handed down by word of mouth over the years? Would not the story told to Rasmussen, as one of the earliest retellings of the story, be as accurate as any later retelling? Herbert has not adequately explained why the initial version given to Rasmussen should be inaccurate while later versions were considered to be accurate.”

This is not to say that because it can be proven inaccurate in some of its stated details, that such folk memories can be safely disregarded as evidence, however, but it should be borne in mind that many human and cultural factors can influence oral traditions and how and why they may vary over time.

Nevertheless, there are some relevant details in the narrative of Ulloriaq that are of interest when comparing it with the various conflicting versions, either by eyewitnesses or parties who retold the story as allegedly gotten from these eyewitnesses, that have already been detailed in this series. Here in italics is a paraphrase of those details derived from Ulloriaq’s narrative and direct quotations from it of points of comparison especially relevant to Dr. Cook’s journey on which he claimed to have attained the North Pole:

According to Ulloriaq, Cook party set out from Annoatok and crossed Smith Sound to Ellesmere Island, following its coast to Bache Peninsula. They went up Flagler Fjord and then up a valley on Ellesmere Island at the fjord’s end in an attempt to reach Bay Fjord, which lay on the other side of the island. They then took a course northwards, skirting Axel Heiberg Island. Along the way they were well provided with food from the many musk oxen they encountered and killed along this route. At one point along the way the Inuit saved Cook during a near fatal encounter with a polar bear.

They reached the tip of Axel Heiberg Island and eventually set out over the sea ice. They knew that they were trying for the North Pole because Cook had, before they set out from Annoatok, shown them on a map where it lay. “They travelled for a long time towards the north on the two dog sledges with the leader out in front on his skis as usual. The whole time they could make out faintly some of the coast of Grand Land [the north coast of Ellesmere Island] . . . Presently they came to large expanses of drift ice and after having travelled through this for some time ice packs came into sight. The leader stopped then and wanted to go no further. . . . They stopped for a long time in an area where there was enormous drift ice and pack ice which had broken loose from the polar ice. They reached the place in the middle of their most hopeless struggle and camped there. Their leader said nothing to them about having reached the North Pole. . . They said they were not so far from land. They of course meant that they could see some of Cape Columbia on the north coast of Ellesmere Land the whole time. It was moreover the place which [Peary] used as a depot and starting point for his [trip in] 1909, when he was on his way to the North Pole. Eventually they turned around and travelled south through the enormous ice packs between which there were large holes in the ice with tracts of open water. They continued down alongside Axel Heiberg Land directly towards [Hassel Sound] before the shady side of Ellesmere Land. . . . Gradually they came to Hell Gate between Ellesmere Land and Devon Island. . . This sound seldom freezes over, especially when the sea currents are stronger than usual. They could go no farther [by sledge]”

They stopped at Hell Gate a long time before taking to the collapsible boat they carried. Because they could not take their dogs with them in the boat, at Hell Gate they abandoned all of them and one of their two sledges. After crossing Jones Sound in the boat they reached the ice fringing the shore of Devon Island and man-hauled their remaining sledge and supplies along its coast. Eventually they reached Cape Sparbo, which they found to be a suitable overwintering place. This was in September 1908. They spent the remaining months of daylight gathering in meat and skins to tide them over the winter and building an underground igloo using wood from the boat and musk ox skin to cover the house’s roof. The result was a warm and comfortable dwelling for the winter.

The Inuit spent the winter in the igloo dressing musk-ox skins and fashioning them into clothing and boots, while Dr. Cook wrote and wrote. Here they decided that Cook had lied to them about reaching the North Pole because they found map among his papers on which he had drawn a route all the way to the North Pole. “Although they believed he was lying they did not change their attitude towards him. They thought a lot of him and they knew he thought a lot of them.”

When the light of the sun began to return they set out for Greenland, “hunting along the way with rifles, harpoons and other weapons with them,” reaching Annoatok again in April 1909. After they arrived “they were interrogated thoroughly as to what the North Pole looked like and whether they had actually reached the North Pole. The polar Eskimos had of course been given to understand by Daagtikoorsuaq that he had reached the North Pole! But when the two young men were asked whether they had really reached the North Pole, they just laughed, perhaps because it made them think of the route which had been drawn to the North Pole but also perhaps because they knew that nothing of the sort had happened. They thought it would be a sin if their leader were to have an inkling of what they had seen. . . . They never dreamed of going along with the joke. I am saying this because I know that later they were interrogated very thoroughly about the North Pole by [Peary] himself. They of course admitted that he had lied. . . . [Cook ] never let the two young men . . . know anything of his lie about them reaching the North Pole. He was able to do this because they did not know where the North Pole lay, or so he thought then.”

Ulloriaq theorized that [Cook] “was clear in his mind that he could not reach the North Pole. He therefore concentrated persistently on the trip to the large drift ice instead. Ulloriaq concluded by saying that although he wasn’t sure whether Cook had adequately rewarded Etukishuk and Ahwelah for their efforts, “I know that the polar Eskimos have nothing bad to say about Daagtikoorsuaq.”

Jean Malaurie, a French geomorphologist turned anthropologist, lived with the Polar Inuit for a time in the early 1950s. In his book, The Last Kings of Thule, he had little to say about what the older members of the tribe told him about any specifics of Cook’s 1908 Journey. Being partial to Cook, he contented himself to repeat the report Rasmussen had given in Cook’s favor in October 1909. Malaurie was more interested in trying to find out what happened to Cook’s belongings that Peary ordered buried at Etah, perhaps believing they contained proof of Cook’s claims, and searched for them without success. But he did expound on what the Inuit said about the personalities of the two rival explorers.

He confirmed that the tribe still held a high opinion of Cook. “Cook was so pleasant, always smiling and eager to help,” one of the Inuit told him. “He could have gotten everything he wanted from us by his charm.” But their attitude toward Peary was a different matter. Even as late as nearly fifty years after his death, it was clear they still held him in awe. In 1967 an old member of the tribe talked with Malaurie about Peary, but only after first carefully checking to see if Peary’s shade might not be listening outside the door. He called Peary “the Great Tormentor.” “People were afraid of him . . . really afraid, like I am this evening. . . . You always had the feeling that if you didn’t do what he wanted, he would condemn you to death.”

After Cook and Peary, the Polar Controversy, resolved was published in 1997, I got more than a few letters regarding it, some from relatives of some of the people mentioned in its pages, and some who wanted to tell me about experiences they had had they thought were relevant to it. One of these letters came from Donald Taub, a retired US Coast Guard captain.

As a junior officer, Taub had spent a year’s tour of duty at a station in Greenland in 1959-60, during which he was in contact with Ere Danielsen and a group of 6-8 older polar Inuit. Danielsen’s father was Puadluna, one of the nine Inuit who had accompanied Dr. Cook as far as the northern tip of Axel Heiberg Island in 1908. At the time, Taub had not studied the Polar Controversy in detail and was of the general belief that both Cook and Peary had reached the North Pole. Danielsen, according to Taub, was a fixture at the station and had been for some time before he came, and was found of telling tales. One evening Taub attempted to show his knowledge of the two explorers’ expeditions by tracing their routes on a navigational chart. When he traced Cook’s route all the way to the North Pole, thinking Ere would be pleased because of his father’s association with it, he got an unexpected reaction. “’No, no no; Here!’ he objected at once, putting his finger tip on my chart, with hand motions etc. of Cook’s ‘turn-around place,’ and ‘everyone’ agreed with him. It came as a surprise. Hence I well remembered it.” Taub spent 12 ½ months with the Inuit, traveled with them by dog sledge, but never learned enough of their dialect to converse with them directly. Most of his understanding came through non-verbal cues, such as hand gestures and facial expressions, though he did sometimes converse using English speaking Danish go-betweens. (letter May 14, 2002, possession of author)

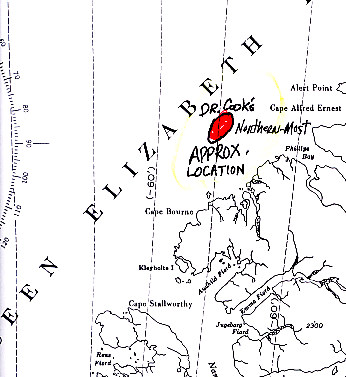

Taub sent me a chart showing the area where Ere put his finger, which was well up the coast of Grant Land, but at about the same latitude Stallworthy reported Etukishook had reported as the site of Cook’s “North Pole” pictures—82º North. But this location is unique among all the reports of Cook’s turn around, either by “eyewitnesses” or secondary sources, demonstrating once more that Inuit folk memory is not always strictly consistent or reliable.

As for Wally Herbert himself, he heard something about Cook’s route from elders of the Polar Inuit, but doubted what he heard. Here’s what he said in his book, Across the Top of the World, of his experiences with them in the 1960s: “Most of the Eskimos with whom we discussed Cook’s claims in sign language believe that the doctor and his two Eskimo companions, after having crossed Ellesmere Island, went southwest instead of northwest; and instead of sledging up Nansen Sound to the northern tip of Axel Heiberg Island (from where he set out across the polar-pack ice toward the North Pole), spent the summer of 1908 hunting in the region of Hell Gate off the southeast coast of Ellesmere Island. The Eskimos are excellent map readers–we could see this from the way they ran their grubby fingers over the map on the inner door of our hut as they vividly described some hunting anecdote, or traced the route we planned on taking, up to the point where they predicted we would perish. They must have known Cook and his Eskimo companions had sledged northwest–the stories handed down over the years could not have been so far distorted. We can only assume, therefore, that the Eskimos told us (as their fathers had told Peary and MacMillan) what they thought we wanted to hear.” Yet twenty years later he insisted “Stories are always retold exactly as heard, not deviating by a single phrase or word.”

The Brooke letter is in the Cook Papers at the Library of Congress.

Filed in: Uncategorized.