The Cook-Peary files: The “Eskimo Testimony”: Part 14: Tracing Cook’s actual route: Part 1.

Written on December 27, 2023

This is the latest in a series of posts that publish for the first time significant documents related to the Polar Controversy.

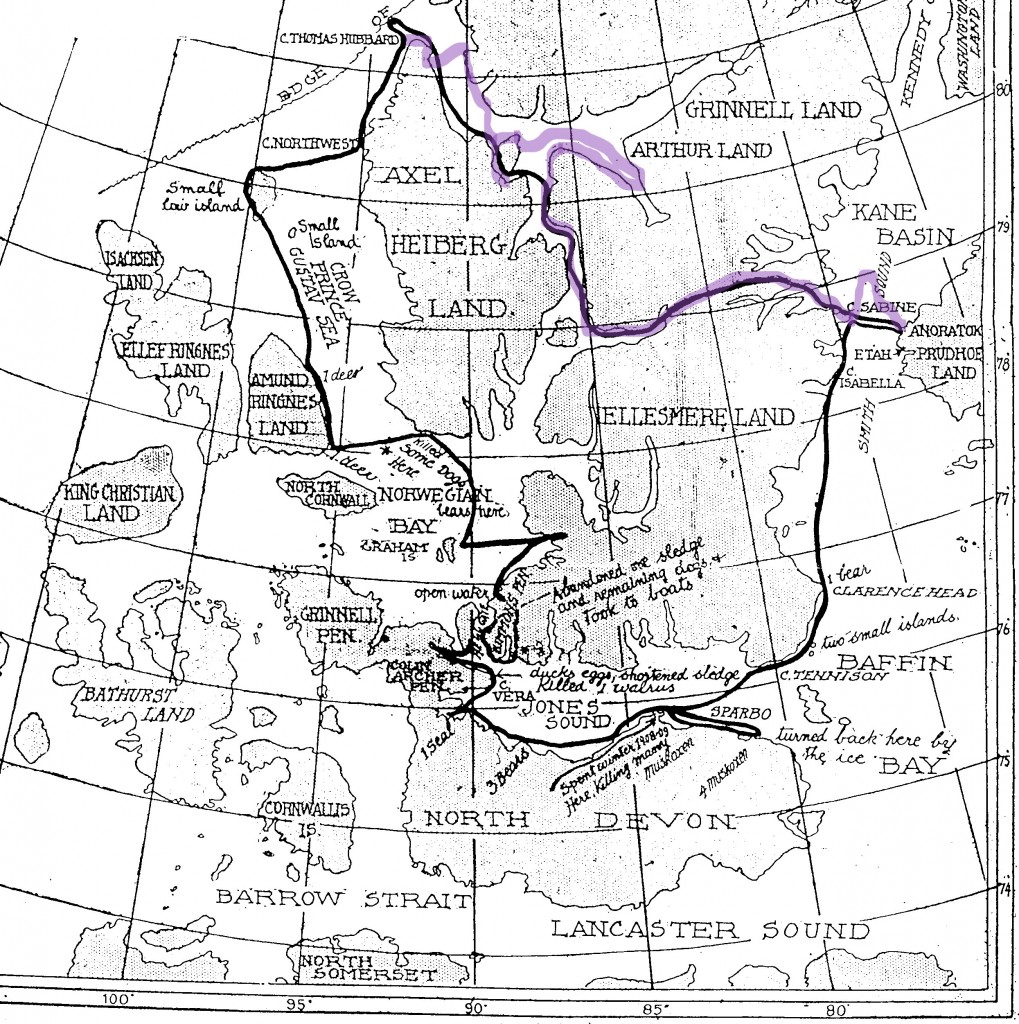

Because, as we have seen, the existing evidence of what the Inuit said to others about their journey with Dr. Cook varies, and is sometimes contradictory, we will now examine how these accounts compare with Peary’s published map on which he said they allegedly traced the route of their journey, and what they say about the accuracy of the route outlined there.

Peary’s map was based on Otto Sverdrup’s map of his explorations of the Queen Elizabeth Islands during the years 1898-1902, and therefore, though not nearly as detailed or accurate as modern maps of the area, it was at the time the best map then available. Using an enlargement of Peary’s published map, we will divide the journey into three parts in an attempt to come as close as possible to a recounting of Cook’s actual journey.

The first leg of the journey is the route Cook took from his winter quarters at Annoatok to reach Cape Thomas Hubbard, where he left land and started out across the ice of the Arctic Ocean. For this part of the journey there is nearly nothing bearing on it in any of the Inuit testimony, either in Peary’s statement or from hearsay from Inuit sources as recounted by third parties, or even in folk memory accounts, for that matter. In fact, it is clear from the route shown on Peary’s map that Cook’s companions were not questioned about this part of their journey in any detail.

Peary knew for sure that Cook had actually reached Cape Thomas Hubbard because one of the Inuit in his party who turned back, Egingwah, had been with Peary, himself, when he had reached the cape in 1906, and was able to verify that Cook had reached the same place. Therefore Peary was not concerned about grilling Cook’s Inuit companions on this segment of the journey, but evidently simply filled in the most direct and logical route any explorer would have taken to get there. In so doing, however, he outlined a route that is inaccurate in many respects.

We know this from an examination of the detailed notebook Cook kept on this leg of his journey and from the eyewitness testimony as recounted by his only civilized witness, Rudolph Franke. Those interested in reading the full account contained in this notebook are referred to the author’s annotated transcription of it (see the post for July 11, 2023). Here we will only note the important points of difference between the route it describes and Peary’s map. We will also note here any points relevant to the folk memory account of Ulloriaq, recounted in Part 12 of this series.

Cook’s notebook, although written during the leg of the journey in question, was later modified by erasures, changes in dates and other means of obfuscation to bring it into line with his eventual narrative, but much of the detail it contains is unaltered and so, along with Franke’s testimony, allows an accurate reconstruction of his actual route. For instance, in My Attainment of the Pole, Cook gave his starting date from Annoatok as February 19, 1908, but from Franke’s account and internal evidence from Cook’s notebook, the actual date he left his winter base was very likely February 26. He was, therefore, already a week behind his published schedule at the very start, and therefore his entire timetable described in his published narrative is incorrect. This is critical because Cook claimed to arrive at the Pole on April 21, and so his timetable being off by even a day rules against the truth of his narrative.

Peary’s map shows him crossing directly across Smith Sound from Annoatok to Cape Sabine. Actually, Cook was diverted north by open water in the middle of the sound and approached Pim Island from the north. This portion of Peary’s original map shows the route allegedly drawn by the Inuit in black. Cook’s actual route is shown in purple where it differs.

Peary’s map shows Cook going around the northern end of Pim Island, while he actually went up Rice Straight, between Pim Island and the mainland of Ellesmere Island, though in the Peary statement’s text, the correct route is stated. Peary’s map is generally accurate from there until he reaches Slidre Fjord on the western coast of Ellesmere Island and turns northwest. Here, it leaves out a significant diversion Cook made to lay caches for his anticipated return through Greely Fjord, Canon Fjord and overland to reach Flagler Fjord as a shortcut to regain his winter quarters. Had Peary gotten an actual description of Cook’s route from the Inuit showing this diversion, he would have obtained convincing evidence that Cook could not possibly have reached the North Pole in 1908.

Cook had read Sverdrup’s account of his crossing of Ellesmere Island via Sverdrup Pass closely and wanted to avoid the delays the Norwegian had encountered there in 1899. He planned to go instead from Flagler Fjord onto the icecap of the island and descend into Canon Fjord and then reach Nansen Sound by way of Greely Fjord, but was unable to find a way onto the icecap because of scant snow cover, and so had to follow Sverdrup’s route. Consequently, he was much delayed in his crossing of Ellesmere, throwing his timetable even farther behind, which ultimately led to him being unable to reach his jumping off place for the North Pole in time to have any chance to reach his goal.

Cook wanted to lay the caches for his return so that he might make use the shortcut to Flagler Fjord on his return to his winter base anyway. By returning by a different route than the supporting party he planned to send back at the edge of the Arctic Ocean, he could avoid running into any witnesses to his movements after separation and thus lock him into a timetable incompatible with any story he might choose tell of polar attainment, and still allow him to remain away from his winter base long enough to have reached the North Pole and returned. Thus the detour into Canon Fjord. This detour, that Peary missed, was one no explorer intent of getting away to the Pole as soon as possible would have taken, and the fact that Cook made it shows that by the time he reached Slidre Fjord he knew he had no chance of actually reaching the North Pole and was contemplating a false claim to have done so.

Instead of the route shown on Peary’s map, Cook continued instead up Eurkea Sound to Greely Fjord, turned east into it, then southeast into Canon Fjord, laid his cache and returned to the entrance of Greely Fjord by reversing his route back to Eureka Sound. From there he crossed to the northern tip of Schei Island, went down its western coast and laid a cache for his supporting party at the base of what was then called Flat Sound, to be picked up by it on its way back to Greenland, thus insuring he would not run into them on his own way back to his base. There he discovered that Shei Island was really a peninsula before resuming his journey toward Cape Thomas Hubbard via Nansen Sound.

It appears from Cook’s notebook, though it is not certain because of changes he made to it, that he crossed Nansen Sound in hopes of finding game on the shore of Grant Land, then crossed back again to Axel Heiberg Island just below the cliffs Sverdrup had called Svartevoeg. He then continued north to Cape Stallworthy, and mistaking it for Cape Thomas Hubbard, tried to locate the cache Peary said he had left there in 1906. Unable to find it, he moved northwestward across a bay to the true Cape Thomas Hubbard and reconnoitered a short distance south from it, looking for the best route to take out over the jumbled ice against the coast. It was from here that the bulk of his supporting party started back to Greenland over their outward route. But to get over this rough ice he took along two extra Inuit and headed out across the sea ice in a northwesterly direction. They remained with him three days before starting for home, catching the others at the big cache in Flat Sound.

That Cook left from Cape Thomas Hubbard and not Cape Stallworthy, seems certain. However, from what he wrote in My Attainment of the Pole, Cook believed Cape Stallworthy, which he called by Sverdrup’s name, Svartevoeg, was Cape Thomas Hubbard. Cook wanted to retrieve Peary’s cairn message to prove he’d been there, and that’s where he says he looked for it, confirming his confusion. This same mistake was made by Donald MacMillan in 1914 when he did the same thing at Cape Stallworthy, and was unable to find Peary’s cairn. MacMillan’s goal was reaching Peary’s mythical Crocker Land, which Peary said lay to the northwest, so it was natural that he travel along the ice foot from Cape Stallworthy to the real Cape Thomas Hubbard before leaving land, and only realized the two places were not the same when he recognized the latter as the actual Cape Thomas Hubbard from Peary’s picture of it in his book, Nearest the Pole.

It’s very possible that Cook also intended to try to reach Crocker Land, viewing it as a way station on the way to the North Pole, either intending to camp there or get the supposed benefits of traveling along its east coast, where its location might be expected to mitigate the prevailing general eastern drift of the pack ice other explorers, including Peary, had previously described. So both MacMillan and Cook would be drawn to Cape Thomas Hubbard as a jumping off place, though neither of them initially realized that they had mistaken Cape Stallworthy for Cape Thomas Hubbard, and Cook probably never realized his mistake. Incidentally, although Peary didn’t realize it, Cape Stallworthy is actually slightly farther north than Cape Thomas Hubbard.

Ulloriaq’s folk memory testimony adds very little to our knowledge of this first leg of Cook’s journey. In fact, it is incorrect in several aspects when compared with Cook’s journal. It does note the presence of open water in Smith Sound, however, but it says that in crossing Ellesmere they had to camp “two or three times on the way.” According to Cook’s notebook, from the head of Flagler Fjord, the party camped six times before reaching Bay Fjord on the west coast of Ellesmere Island.

In summary, we can conclude that, for this leg of Cook’s route, what Peary claimed was told to him by the Inuit, as evidenced by the route outlined on his published map, is a poor match to Cook’s actual route in many important ways.

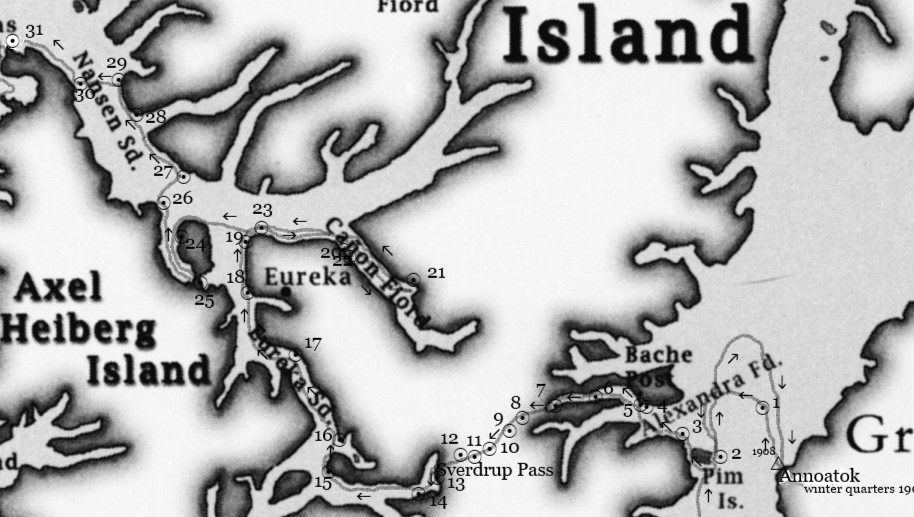

Here is a modern map of Cook’s actual route showing his camps along the way as circled dots, the last at Cape Thomas Hubbard being #31, taken from The Lost Notebook of Dr. Frederick A. Cook.

This map is copyright © Jerry Kobalenko and used by permission in that book.

Where Cook went after he left Cape Thomas Hubbard until he returned to land again is the most uncertain leg of his journey and has the least evidence to come to any definite conclusion. Therefore we will leave that aside for the present, and next examine the third leg: from the time he said he returned from his successful attainment of the North Pole until the time he regained Annoatok in the Spring of 1909.

Filed in: Uncategorized.