The Cook-Peary files: The “Eskimo Testimony”: Part 15: Tracing Cook’s actual route: Part 2: Two irreconcilable accounts.

Written on January 29, 2024

This is the latest in a series of posts that publish for the first time significant documents related to the Polar Controversy.

A further assurance that the Inuit did not draw the first leg of the journey from Annoatok to Cape Thomas Hubbard on Peary’s map is that nowhere along that route do they indicate any specific kills of game. Peary’s statement simply stated that they killed polar bears and musk oxen along the way. However, on the rest of the route game kills are specifically noted. Hunting was an Inuk’s life, and knowing where game could be found meant his very survival, making it always uppermost in his mind. So the notation of specific game kills would naturally be something Cook’s Inuit would remember in detail.

There were only three witnesses to this third leg of the journey, from when Cook reached land again until he arrived back at his winter base in Greenland: Cook, Etukishuk and Ahwelah. Unlike the first leg, there is no original diary by Cook of this portion known to exist. Nor do the “field notes” appended to My Attainment of the Pole cover this period. The only detailed sequential description Cook ever gave was in his book’s narrative. Peary alleged that the Inuit described the return journey to his interrogators in some detail and traced their route on the map he published showing the route of their travels from the Polar Sea until they regained Annoatok in April 1909. The two versions, Cook’s and the Inuit’s, of where they went and what they did are markedly different, and so cannot be reconciled with one another before a certain point. It is Cook’s word against what Peary says the Inuit reported to his men. So we must review what each account claimed before we consider each of these versions to see which one is the more plausible.

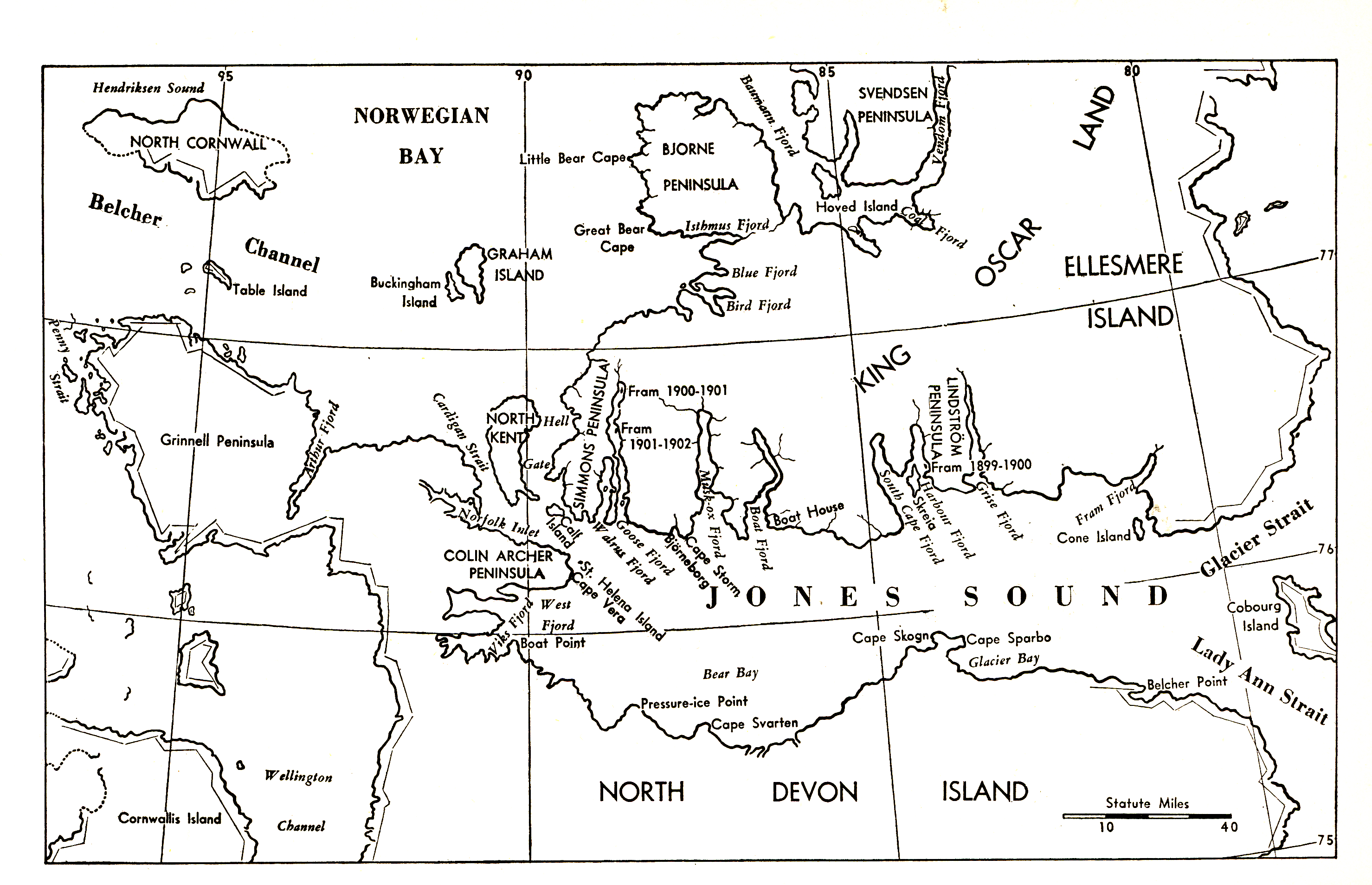

This map shows many of the places mentioned in the two accounts which follow:

Cook’s version

Cook stated that for an extended period as he approached land from the Polar Sea, he was enveloped by fog and was unable to get his bearings. He was only able to get a navigational sight to determine his position on June 13, 1908. That sight placed him at latitude 79°32’, longitude 101°22’ in the Crown Prince Gustav Sea. Therefore he had unaccountably drifted much farther west than he expected. Although he could see the cliffs of Axel Heiberg Island about 50 miles to the east, he couldn’t hope to reach them because of the condition of the ice, which at this point, he said, was much broken and drifting south; he therefore had no choice but to drift with the ice southward.

• The drift was S-SW, and he could see what appeared to be the Ringnes Islands in that direction separated by Hassel Sound.

• He reached the ice foot surrounding the islands and made land fall on a small island just above Amund Ringnes Island, where he camped.

• He then passed through Hassel Sound, killing a bear, the first game they had killed since leaving land. More bears were killed as they progressed south through the sound.

• After clearing the sound, he was unable to go to the east because the ice conditions in Norwegian Bay were the same as those that had prevented him from reaching Axel Heiberg Island from his initial position—small ice drifting southward.

• So he set off across the ice into Wellington Channel with the southerly drift with the idea of reaching Lancaster Sound, where Scottish whalers visited every year. He was now west of North Cornwall Island and he could see King Christian Island in the distance.

• They now drifted into Penny Strait, midway between Bathurst Island and the Grinnell Peninsula of North Devon Island.

• At Dundas Island the drifting ice stopped, and they made for the Grinnell Peninsula hoping to follow the smoother ice foot there along the shore of North Devon to reach Lancaster Sound.

• They went along the shore of Wellington Channel as far as Pioneer Bay, where they were stopped by a jam of small ice impossible for sledging. Here they were able to kill some seals and also some caribou.

• Unable to proceed farther south, on July 4, 1908 they turned east to cross the peninsula. At first, going was difficult because of bare ground, but a provident 2-day snowstorm soon covered it and made for good going. It took four days to reach Sverdrup’s Eidsbotn on Jones Sound on July 7.

• Because the southern shores of Jones Sound were packed with raftered ice, they abandoned their dogs near Cape Vera and took to a folding canvas boat they had carried with them for crossing leads.

• They progressed east two weeks in the boat and were approaching Cape Sparbo, when they were caught in open water by a sudden storm. With the drift ice threatening to crush the boat, they hauled it out onto a passing ice floe, but even this didn’t guarantee safety. They managed to scramble with their boat onto a low passing iceberg, but the berg was blown by the gale back across the sound nearly to Hell Gate.

• The berg was being wind-driven toward Cardigan Strait, where it grounded about 10 miles off Cape Vera, which they now attempted to reach. After nearly sinking after the boat was holed by ice during an attempt to reach shore, the boat was hauled out and patched with a boot before they reached land again north of the cape. They were about back where they had been three weeks before.

• Traveling from there along the southern shores of Jones Sound by sledge, when practical, and by boat across patches of open water, they made an average of about 15 miles a day, finally clearing the land-packed ice about 25 miles west of Cape Sparbo early in August.

• Here they killed an oogzuk seal. East of Sparbo the boat was holed by a walrus, but was hauled out and patched again.

• About August 7 they reached Belcher Point, and turned south into the unnamed bay beyond it. After a run of ten miles to the east they were driven into the pack that filled the bay to seek shelter from another storm. There they remained imprisoned for most of the rest of the month, drifting slowly back toward Belcher Point again.

• Further progress east was futile, so they turned back for Cape Sparbo, where they had noted an abundance of game in passing east, reaching it again in early September. There they found an old subterranean Inuit dwelling and after digging it out fitted it up for the winter, killing musk oxen to provide winter stores of meat and fat for fuel.

• Cook wrote a long account of the winter they spent there, saying they were reduced to the level of Stone Age hunters to eke out their survival, as they had almost no ammunition left and had to create new weapons from what materials they had on hand, using parts of their remaining sledge.

• On February 18, 1909, when the sun returned, they started for Annoatok. It took eight days to reached Cape Tennyson, discovering two new islands to the east of it, which Cook named for his two Inuit companions.

• From there they crossed the ice to Cape Isabella. They next reached Clarence Head after being delayed by storms, and finally landed at Cape Faraday on the 35th day out from their winter camp. On March 20 they were able to kill a bear with one of their final cartridges, saving themselves from starvation.

• During the final 100 miles to Cape Sabine, food ran out, and they were saved by shooting another bear. But that was gone before they reached their destination, but there they discovered a cache containing a seal that left by Panikpa that saved them from starvation. After resting at Peary’s caboose at Payer Harbour, they had to make a long detour north before finding ice stable enough to cross Smith Sound, reaching Annoatok again on about April 15, 1909.

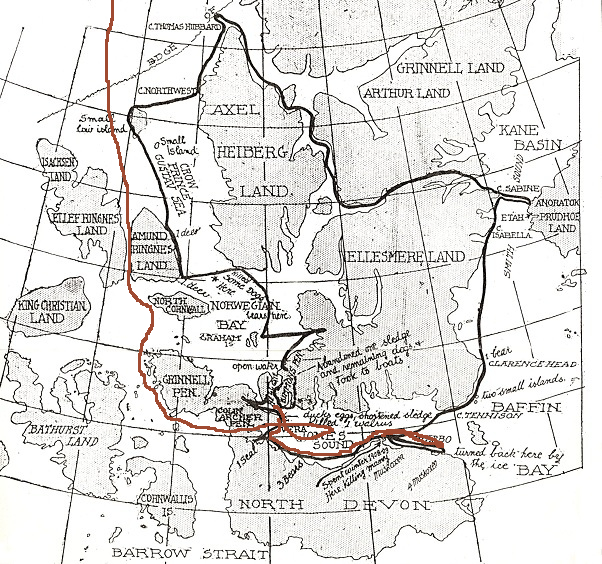

This portion of Peary’s published map shows the route allegedly traced by Cook’s Inuit in black; Cook’s claimed route is shown in brown.

The Inuit version

The story told by Cook’s Inuit was related in Peary’s published statement of October 13, 1909, accompanied by a copy of Sverdrup’s chart, upon which Peary said they traced their route. (See Part 2 of this series). This was supplemented by further details contained in Donald MacMillan’s 1917 letter to the American Geographical Society, which they published in 1918. (See Part 5 of this series). The folk memory account adds only the Inuit opinion of the winter at Cape Sparbo and a few slight details to these two accounts. (See Part 12).

Returning from the Polar Sea, they gained land again west of the point where they had left the cache on the shore of Axel Heiberg Island. Here they camped four or five days. During that time Etukishuk returned to the cache to get a gun he had left there and only a few other articles, because the sledges were still loaded with supplies. They then turned south.

• They went down the west coast of Axel Heiberg Island as far a Cape Northwest.

• From there they set out west across the snow-covered ice to a low island they had seen from Cape Northwest.

• They went down the west coast of this island, then headed southeast toward Amund Ringnes Island, passing another smaller island that lay to the southeast of the larger one they had visited.

• When they reached Amund Ringnes Island, they traveled the length of its east coast, where they secured two reindeer.

• From there they crossed Norwegian Bay, and after killing some of their dogs, they reached the southern shore of Axel Heiberg Land, where they killed a bear.

• Continuing south they passed by the east side of Graham Island.

• From there they reached Eid’s Fiord (Isthmus Fjord on the first map), a small bay marked on Sverdrup’s chart.

• From this bay they continued southwest to Hell Gate’s north entrance near Simmons Peninsula. It was here that they encountered the first open water they had seen since they had turned back form the Polar Sea. They spent “a good deal of time in this area,” before moving on.

• Unable to proceed along the coast to the south because of the open water, they crossed Simmons Peninsula and sledged down the length of the frozen-over Gaase Fiord (Goose Fjord).

• When they reached its entrance, they turned west, then north into the channel of Hell Gate. They crossed Hell Gate to North Kent Island, then went up into Norfolk Inlet, where they again encountered open water and could proceed no farther by sledge. So they abandoned their dogs and took to their collapsible boat. One of the sledges was also abandoned.

• Using the boat, they traveled along the northern coast of Colin Archer Peninsula to Cape Vera, where they secured the eggs of nesting eider ducks. Here they shortened the remaining sledge because if was too awkward to carry in the boat. Near here they killed a walrus, and at the southwest angle of Jones Sound they killed a seal.

• Following the south shore of Jones Sound eastward they killed three bears.

• When they reached Cape Sparbo, they killed several Musk Oxen, and east of it they killed several more.

• They were stopped by ice packed against the shore as they approached the mouth of Jones Sound and turned back toward Cape Sparbo again. There they made a comfortable shelter using an ancient Inuit stone igloo as its base. They had plenty of ammunition and killed musk oxen and bears at will, providing them with a wealth of meat and fat for fuel for the winter. They settled into their comfortable dwelling to pass the winter, the Inuit spending the time curing musk ox skins and from them creating new clothing, including pants and boots, to replace their worn out garments. Cook spent his time writing endlessly in his little notebooks.

• When the sun returned in February 1909, they crossed Jones Sound to Cape Tennyson, passing inside two small uncharted islands, where they killed a bear.

• From there they continued north to Clarence Head.

• Then then crossed the frozen inner bight to reach Cape Isabella, killing another bear, and then went on to Payer Harbor, where they stayed in Peary’s house there. At Cape Sabine they found a cache containing a seal left for them by Etukishuk’s father, Panikpa.

• From Cape Sabine they crossed Smith Sound to reach Annoatok once more.

In the next post we will take up the question of which of these stories is the more plausible.

Filed in: Uncategorized.