The Cook-Peary files: The “Eskimo Testimony” : Part 16: Tracing Cook’s actual route: Part 3: Testing the two accounts.

Written on February 19, 2024

This is the latest in a series of posts that publish for the first time significant documents related to the Polar Controversy.

Immediately upon the publication of Peary’s statement about what Cook’s Inuit said appeared, partisans of both sides noticed the extreme differences in the route on Peary’s map compared to the one published by Cook in his New York Herald narrative. Along with its publication of Peary’s statement, it ran the arguments and counter-arguments of partisans on both sides. Cook’s supporters contended that “Even if Dr. Cook’s story of his polar dash were false, he would not be expected to give an incorrect report of his travels after he returned to regions where his trail might be followed and his camping places visited for verification of his story.” Peary’s supporters countered, “That Dr. Cook naturally would wish his route southward supposed to lie to the west of that which the Esquimaus described. He said in his narrative that he was pushing for Lancaster Sound where he hoped to find a whaling ship. The route which he gave was the most direct on to reach Lancaster Sound. If he had, as the Esquimaus say, reached the southern point of Heiberg Land and pushed thence [east]ward, he would have been within easy reaching distance of his caches and the trail by which he had gone west, and so might have returned to Etah in the early summer of 1908.”

When the testimony of the eyewitnesses is in direct conflict, then one must fall back on circumstantial evidence to see which of the stories is more likely. This evidence comes from comparing each of the descriptions given by the conflicting witnesses to see how well they match up with the experiences of others who traveled over the same area and the patterns of environmental conditions now known to exist in the area described in the conflicting narratives.

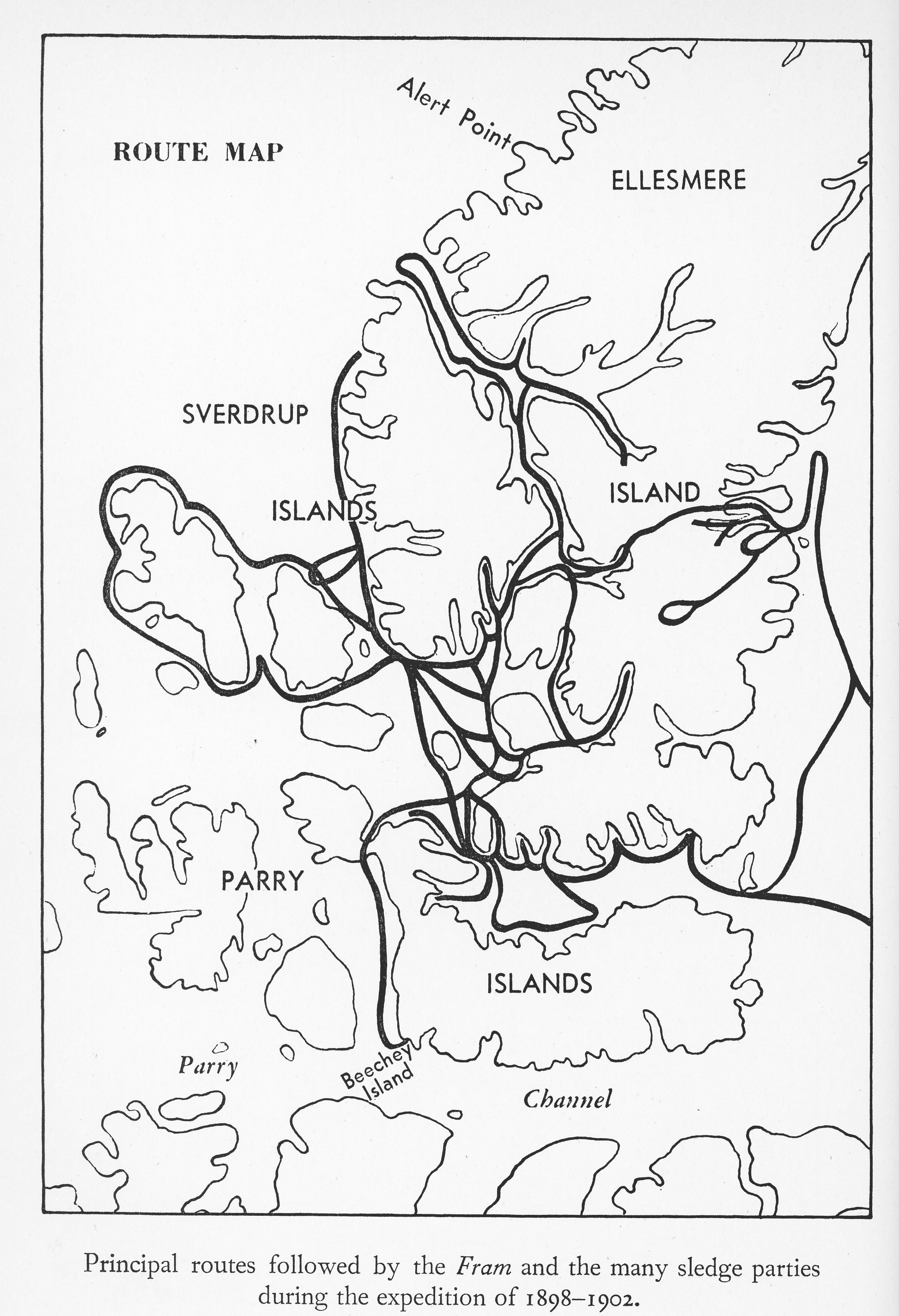

As we have already seen (see Part 11) the arguments over whether Cook visited Meighen Island are irrelevant because he could have actually been at the position he gave for June 13, 1908 on a return journey from the North Pole and not have seen it. The Sverdrup expedition’s parties traveled extensively over the area between 1898-1902 and never saw it. In fact, it was among the very few significant pieces of land that his expedition failed to discover. Here is a map showing the routes of Sverdrup’s travels, showing that on several occasions his journeys brought him as close to Meighen Island as Cook’s reported position without him seeing it. This might be explained by the fact that in summer, when Sverdrup’s parties were in the field, the island is often covered by fog. If the Inuit narrative is true, Cook would have been in the area earlier than that. So the fact that Cook saw it and Sverdrup did not, weights in the favor of the Inuit version.

So, although he denied it, Cook probably did discover and visit the island. The Inuit say they saw it from Cape Northwest, a distance of about 25 miles away, and crossed over the ice to it, traveling around the top point of the island and then down its west coast. The shape of the island on Peary’s map and its very accurate placement there—even better than that of its “discoverer,” Stefansson, in 1916–argues strongly for the accuracy of the Inuit version. If Cook did discover the island, it would have been his first discovery of unknown land, so why, then, did he not report it? As mentioned before, his failure to do so is probably linked to his ignorance of the use of a sextant. Any report of new land would have to include fixing its geographical coordinates. Not being able to do so with any accuracy would have given away Cook’s inability with a sextant, and without that critical skill no journey to the North Pole would have been possible in Cook’s time.

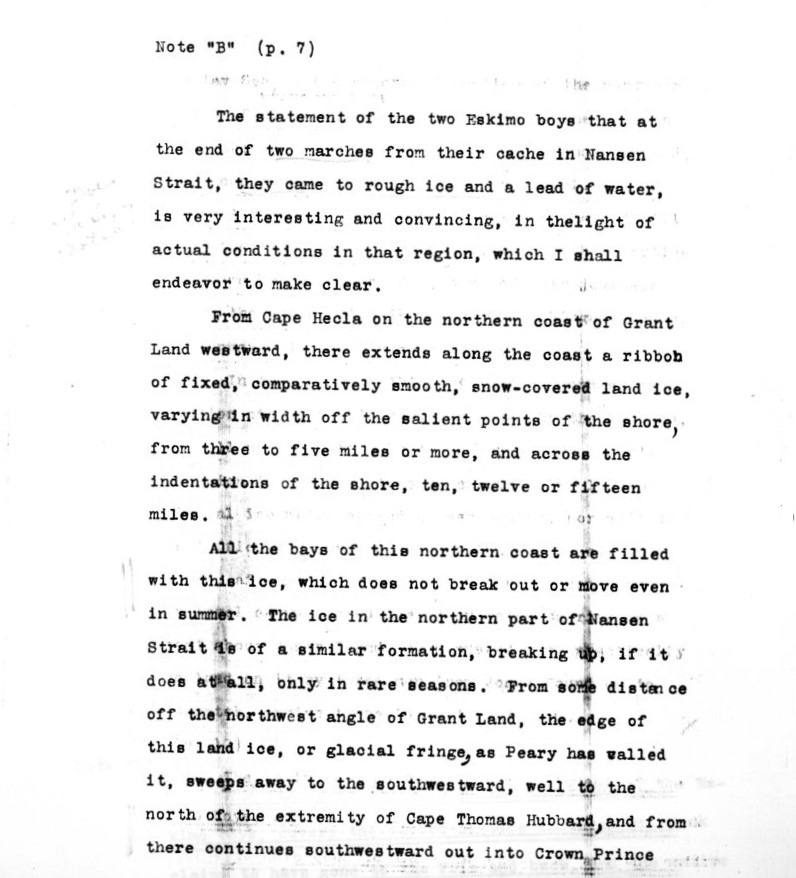

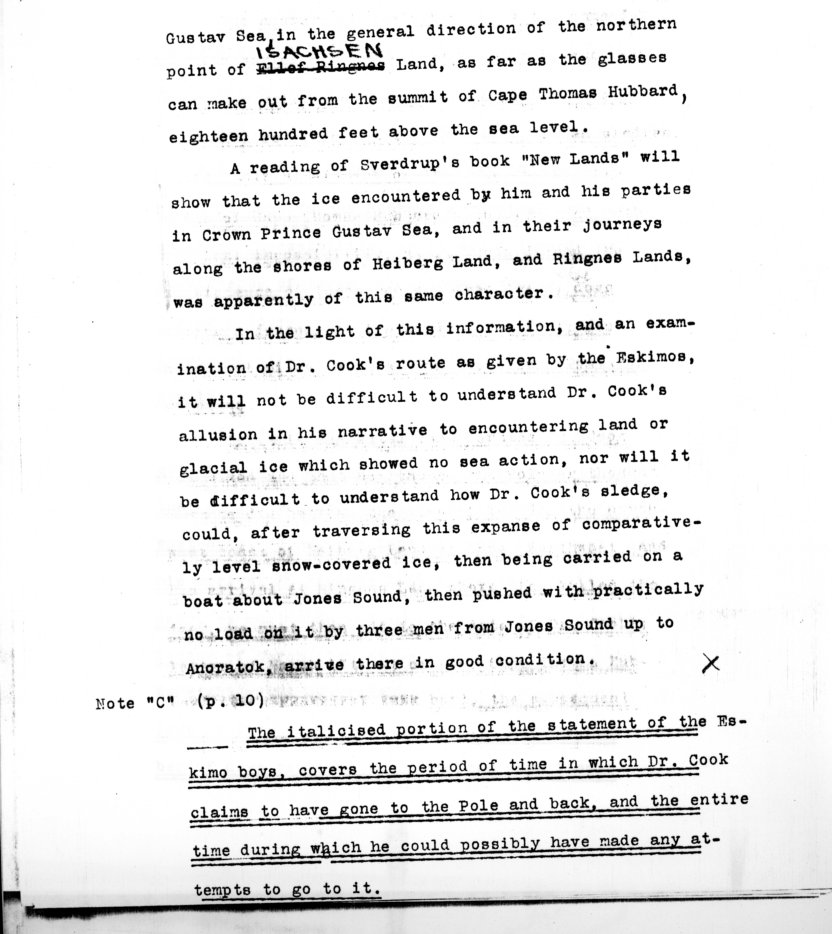

Before Cook, the only parties to travel over the area where Cook next claimed to have gone were those of Sverdrup. They noted that the pull of the moon had no effect on the ice between the Ringnes Islands and Axel Heiberg Land, which remained intact throughout the summers they traveled there. Peary had never been over that area himself, but from Sverdrup’s descriptions and his own observations from the heights of Cape Thomas Hubbard in June 1906, he had formed the opinion that the ice between those islands never broke up. In a statement he sent to General Hubbard as a supplement to the Inuit statement he planned to publish concerning what they had told his interrogators of Cook’s movements, he had this to say:

Not only Sverdrup, but all those who traveled that way in the 20 years after 1908 confirmed that the ice never broke up even in late summer. Stefansson journeyed extensively over the area in 1915-16, for instance, and said that, although the surface melted into slush that impeded travel and deep ravines developed in the ice from run off, it never broke up. Stefansson was able to cross over to Amund Ringnes Island from Axel Heiberg Island in late July 1915. The Inuit told Rasmussen (see Part 7) that the reason they were unable to reach Axel Heiberg was due to “cracks in the ice,” not because it was adrift, closely conforming with Stefansson’s description. Yet Cook described “open water and impossible small ice as a barrier between us and Heiberg Island” in June 1908, and that those same conditions prevailed in Norwegian Bay, preventing him from crossing from Amund Ringnes Island to Axel Heiberg Island shortly thereafter. Further evidence indicates that this could not be due merely to chance seasonal differences from year to year.

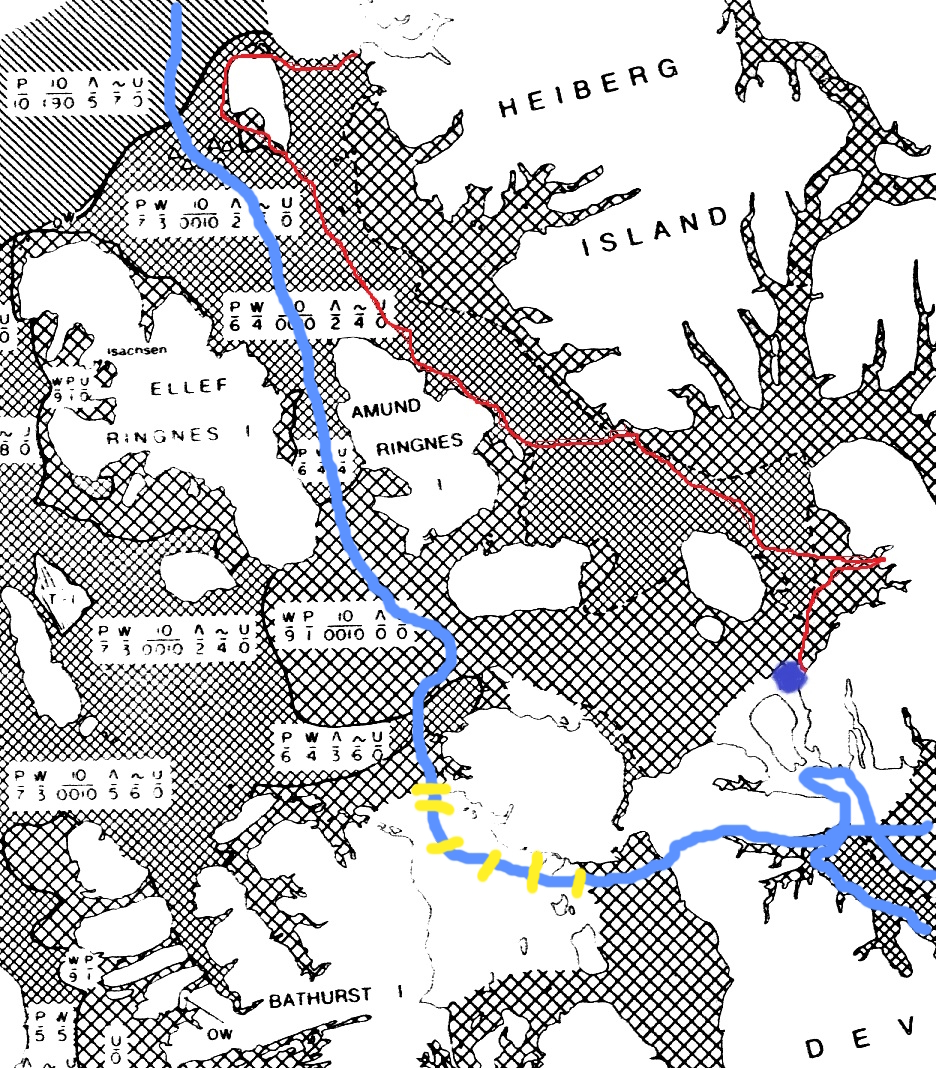

Regular aerial ice surveys carried out by the Canadian government between 1961-1974 showed that the ice is solid between these islands at least until August and starts to break, if at all, even in the extreme south, only in September. Other than that, every year of these ice surveys showed that the ice between them was totally consolidated, with no open water. Moreover this was shown to be multi-year ice, meaning it never melted in an average year. And climatic records and the oral traditions of the Inuit, who have infallible memories in such matters, indicate that, if anything, arctic winters were far colder prior to 1920.

Here’s a sample map from the Sea-Ice Atlas of Arctic Canada 1961-1968. This map shows ice condition in the area through which Cook passed in June 1961, the same month Cook claimed to have been there. The small cross-hatching represents multi-year ice, the larger cross-hatching one to two year old ice. The route the Inuit say Cook took is shown in red. The one Cook said he took is shown in blue. Notice that Cook’s route reaches a large area of open water of Penny Strait, between Bathurst Island and Grinnel Peninsula (marked on his route by yellow hashmarks) that would have stopped his progress via sledge, whereas, the Inuit route is all over fully consolidated ice until he reaches the open water caused by the northern end of Hell Gate, indicated by the blue dot.

Therefore, if Cook was actually at the position he claimed on June 13, 1908, it is extremely unlikely that he would not have been able to return to his caches on Heiberg Island by either route and make his way back to Greenland that same year. It is a near certainty that he could have easily crossed Norwegian Bay to do so if he had wanted to reach Axel Heiberg land from his claimed route. So all evidence indicates that by June 13 Cook was far south of his reported location and simply guessed at the ice conditions where he claimed to have been, based on his experience with the ice in Smith Sound and Melville Bay. Open water and drifting ice in June did not occur in the region through which he traveled well into the 1990s. Again, the Inuit version is a far better match for the conditions that would most likely prevail over this area.

From his stated position, Cook claimed to have made landfall on a small island above Amund Ringnes Island, then traveled with the moving ice down Hassel Sound which separates the two Ringnes Islands. There is a small island off the NW tip of that island at about 78°50N/98°W that is in line with Cook’s reported route through Hassel Sound, but there is also one in Geologist’s Bay that is in line with the rout shown on Peary’s map. Sverdrup reported that Hassel Sound was but three miles wide, but this was but a guess. As can be seen from the above map of Sverdrup’s travels, none of his parties ever actually passed though Hassel Sound, only approaching each of its entrances. The sound is actually 16 miles across, not three. Cook was a meticulous observer of what he actually saw. A case in point is Sverdrup’s “Shei Island,” which Cook reported was actually a peninsula, which later surveys confirmed. If he had actually passed down Hassel Sound, he surely would have reported Sverdrup’s error there as well. So, again, the Inuit version of passing along the east coast of Amund Ringnes seems the more likely, as is their claim to have killed reindeer there. Amund Ringnes is known to be inhabited by reindeer, whereas they are absent from much of the surrounding area.

The Inuit version stated that they encountered no open water between the place from where they turned back on the Polar Sea until they reached the northern entrance to Hell Gate. Again, this is far more plausible than Cook’s account of ice conditions. It is known today that a polynya (an upwelling of warm water) at that location keeps the water open there even in winter. It was at that point, the Inuit version says, that they “spent considerable time,” perhaps waiting for the water to freeze over, so they could continue sledging south along the coast. Since the water never froze, they then crossed Simmons Peninsula to Gaase (Goose) Fjord by way of a broad glacial valley. The Fram had been frozen in near the head of this fjord in 1900-1901, and had not been able to escape, being frozen in about half way down the fjord for the next winter, breaking free only on August 6, 1902. While the Fram was frozen in, Sverdrup used this valley to gain access to the areas west of his winter quarters, so it would have been known to Cook that the frozen waters of the fjord would provide good sledging to Jones Sound. Notice that in 1961, Goose Fjord was ice free, as it was when Sverdrup sailed the Fram almost to its head in 1900 before being frozen in; in 1908, according to the Inuit, it was frozen over, allowing Cook to sledge down its length. Sverdrup during his stay there found the latter case to be the predominate one.

That Cook took this route is not readily apparent from reading Peary’s published account, which does not mention it at all. But the crossing of Simmons Peninsula and the subsequent journey down the length of the fjord are shown on the map that accompanied it. These details were only explicitly mentioned in Donald MacMillan’s letter to the American Geographical Society in 1917. There he also mentions that Cook, after exiting the fjord, went west, then north to North Kent Island, as Peary’s statement had said. There, according to MacMillan’s 1917 letter (see Part 3) Cook’s party again met open water and had to abandon its dogs and take to the folding boat, in which they proceeded across Hell Gate and into Norfolk Inlet. From this point they followed the coastline past Cape Vera, where the Inuit said he arrived in time to gather eider duck eggs, which would have been about the first week in July, according to Sverdrup’s accounts of his own experiences.

Cook’s story of being blown back down half the length of Jones Sound after taking refuge on a passing iceberg as they approached Cape Sparbo, is surely a fantasy to thrill the readers of My Attainment of the Pole, as any such incident would surely have been recounted by his Inuit companions. Yet in no instance did anyone who heard Inuit gossip of the journey hear anything about it. Both accounts coincide fairly well from the point they reach Cape Sparbo the first time. Both say they turned back near Belcher Point to return to Cape Sparbo for the winter. It might be noted here that Cook did not camp at the point on modern maps that is now labeled “Cape Sparbo.” There are twin headlands there, the more westerly one is today is called Cape Sparbo. But Cook wintered at the more easterly one, today called Cape Hardy. In Cook’s time, the westerly cape was called Cape Skogn.

Cook’s tale of spending a “stone age” winter, bereft of most civilized means, greatly impressed many, including Knud Rasmussen. But Cook’s enchanting survival saga of this overwintering, we now know is as untrue as his wild ride down Jones Sound on an iceberg. The proof comes from his own hand, in the form of a sketchy diary he kept over the winter of 1908-09, now at the Library of Congress. It shows that they constructed a comfortable house, which he describes in much detail in another of his diaries, similar to those used in that time to overwinter in Greenland. Using the stone foundation of a similar ancient structure, they dug it out, then used some washed up whale bones for rafters, which they covered with turf. The inside was lined with the skins of musk oxen which they slaughtered at will. These kills are documented from the day of their arrival at the site, killing a walrus on their first day there, September 1, and three musk oxen the next day. The house was visited in 1910 by Bob Bartlett, who found it still snugly lined with furs, though the roof had fallen in. Cook records in his diary that several of the animals were taken with “lines and stones,” so the Inuit folk memory account (see Part 13) may be true. Given unlimited ammunition, the Inuit would likely have slaughtered all of the musk ox in the area. So to restrain this temptation, Cook, according to Ulloruq, restrained this urge by withholding it. Cook also confirms the story about the polar bear that bothered them in his diary. Rather than half the sledge being sacrificed to make new weapons for the hung, in his diary Cook recounts how they found a washed up hatch cover, the wood of which was used to fashion harpoon handles, leaving aside the real reason for shortening the sledge because it was simply “awkward to carry in the boat.” Indeed, Cook’s diary confirms the Inuit account of a comfortable winter, with plenty of food and fuel and ample ammunition. As his entry for October 4, notes: “Slept 10 hours; wonderful dreams. 4 hours eating & exercising together 6 hours; writing 4 hours.”

Cook’s narrative account of his “Stone Age winter” spent at Cape Sparbo was his master stroke. Captain Schoubye said when he heard about it that he could understand why a man like Cook could have reached the North Pole. Rasmussen was so impressed by it that he said “This man who practically alone has gone through and endured the winter at Cape Sparbo and the terrible march up to Anonitok through deep snow and violent ice-crushings, in darkness and bitter cold, has deserved to be the first man at the North Pole.” And Captain Hall just couldn’t think of a reason why any sane man would chose to spend such a winter under such conditions if he had had the choice to return to Annoatok that same year. But the Peary partisans had a simple answer to why Cook would have made such a choice. “He wished, however, to spend the winter away from Etah, in order to avoid Commander Peary, and to prepare his account of the journey.” (New York Daily Tribune, October 13, 1909). All evidence shows that that is exactly what he wished.

The Inuit account of making new clothing from musk ox skins is confirmed by a number of pictures in My Attainment of the Pole. There he describes their outfits before they left for the pole, saying they wore blue fox kapitahs (jackets) and seal skin boots. The pictures taken early in Cook journey, when they were on their way to Cape Thomas Hubbard, show the Inuit thus attired. But some of just Etukishuk or Ahwelah (see Part 8 of this series) show them wearing jackets and boots made of the distinctive long-haired fur of musk oxen, including the one of Etukishuk and Ahwelah standing next to the igloo “at the North Pole.” Therefore, these had to have been taken in 1909, not 1908. This supports MacMillan’s claim in his 1917 letter that those pictures, including the one of the “North Pole” were taken at Cape Faraday on the spring journey home in 1909.

The two versions of the spring journey back to Annoatok coincide with each other in almost every important detail, including the sighting of two uncharted islands off Cape Tennyson, which Cook named after his two companions, today known as the Stewart Islands, which, unlike Meighen Island, there is no doubt Cook discovered.

So we can see that the Inuit version of the story is supported in nearly every detail, whereas Cook’s is very short on corroborating points. Only one exception to this pattern occurs in MacMillan’s letter account. In it he says that “Two low islands were discovered in about latitude 79°, very low and about five miles from land.” Captain Hall attempted to chart these islands to show that this conflicted with the Peary account, placing them along the shore south of Cape Levvel (see Part 9 of this series). What MacMillan was referring to is unclear and may just be a simple mistake. In any case, there are no small islands on Axel Heiberg’s west coast anywhere near 79° and none below Cape Levvel all the way to Cape Southwest, where MacMillan says they landed after crossing from the east coast of Amund Ringnes Island.

On the basis of this comparison of the two stories with circumstantial geographical evidence about their respective routes, as well as documentary evidence in the form of Cook’s own winter sketch diary, we can safely conclude that the Inuit version is far closer to the truth than Cook’s.

The Peary notes on ice conditions are now in NARA II

Filed in: Uncategorized.