Enter Dunkle and Loose.

Written on December 9, 2009

The paper that does things

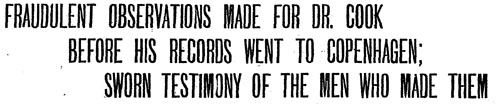

Today the New York Times enjoys a preeminent place in American media, and this day marks the hundredth anniversary of a little known media event that could be said to mark the beginning of the upward rise of the paper to its current status. On this day in 1909 the Times devoted nearly three whole pages to the individual affidavits of two unknown men: one an insurance salesman named George H. Dunkle, and the other an itinerant Norwegian sea captain, August W. Loose. In two separate sworn statements, they claimed to have been hired by Frederick A. Cook to manufacture a set of astronomical observations that would deceive the scientists at the University of Copenhagen, who had agreed to examine Cook’s “proofs,” that he had reached the North Pole on April 21, 1908.

This was a master stroke in the ongoing Polar Controversy, and it is no exaggeration to say that the prestige the paper gained by ultimately coming out on the winning side in the great dispute between Cook and Peary contributed largely to its ascent and the eventual decline of the New York Herald, which had backed Cook. As one commentator put it at the time, “The great victory won by the New York Times in the polar controversy … is recognized… the world over … as making more firm the reputation of the Times as a newspaper that does things.”

But there were others suspicious of just how much the Times had actually “done” in obtaining these affidavits. “It must not be forgotten,” reminded the Rochester Post-Express, “ that the paper publishing the story has been bitterly opposed to Dr. Cook from the beginning. We do not insinuate that the New York Times would deliberately print a false story against Dr. Cook, but under the circumstances it is conceivable that the paper might fall a victim to such adventurers as Dunkle and Capt. Loose. If the story prove false, then there is some truth in [the] charge that a conspiracy is at work against the explorer. If it prove true, then the most charitable conclusion would be that Dr. Cook is a madman.”

The Nation agreed, but noted: “The affidavits are so circumstantial that it is difficult to doubt their truthfulness, but why did Cook fail to pay them their price, when the betrayal of the secret was sure to follow? There is more in all this than is natural.”

The Dunkle and Loose affidavits did, indeed, ”prove true” in all circumstantial aspects that could be independently verified. Yet, the suspicions of how the New York Times got the story seem to have been justified, since William C. Reick, the Times’ city editor, may have been the one who put the two up to it. His motive? He bitterly hated his former boss, James Gordon Bennett, owner of the Herald, and wanted revenge for his treatment at Bennett’s hands by discrediting Cook, whom the Herald had been booming in its pages for weeks.

Some editors, who saw a connection between the Times’ scoop and the enmity it had shown Cook from the start, suspected as much, since they could scarcely believe that Cook would enter into so risky an arrangement with total strangers. To them, that possibility seemed preposterous, the alternative monstrous, and the conclusion obvious: “Dr. Cook is either the greatest and at the same time stupidest charlatan who ever attempted to impose upon a skeptical world, or he is the victim of the most malignant and devilishly ingenious persecution that hatred and envy could devise,” the Philadelphia Record opined. ”Last week it was still the thing to maintain that the astute doctor could have made up a perfect set of polar observations, 800 miles form the pole, while wintering in an arctic igloo; this week the same doctor is suddenly transformed into such a pitiful ignoramus that Dunkle and Loose become his indispensable $4,000 aids in the forging of the precious records. Doubtless the Danes have perspective enough to see the uproarious absurdity of the contrast,” concluded the Springfield Republican.

Time would soon tell, however, which speculations were correct, because Cook’s “proofs” had already been delivered to the Danish scientists and were locked away in a bank vault in Copenhagen when the Dunkle and Loose affidavits were published. The question now was: did they contain Loose’s alleged forged data, or not?

All those who had followed the Polar Controversy for more than three months, now awaited for the Danish decision.

Filed in: News.