The Doctor’s Danish Denouement.

Written on December 21, 2009

The Copenhagen Decision

Today is the hundredth anniversary of what the newspapers called “The Copenhagen Decision.” It marked an end to Frederick Cook’s credibility in most people’s minds.

In September, when he accepted its honorary doctorate, Cook had promised the University at Copenhagen that he would submit his “proofs” that he had been first at the North Pole, and these had been delivered by his private secretary in early December. On December 16, the commission of Danish experts had sat to consider them.

They consisted of two documents: one was a typewritten report, 61 pages in length, substantially a repetition of the narrative that had been published in the pages of the New York Herald. The other was said to be a complete and exact copy of the entries written in one of Cook’s notebooks between March 18 and June 13, 1908, the time Cook said he was on his way to the Pole and back again, covering 16 additional pages. None of Cook’s original notebooks were submitted for examination. The Danes found that the typewritten information contained no original astronomical observations whatsoever, only results.

In just one day, the Danes announced, the “Commission singly had acquainted themselves with the material received and so had convinced themselves that it was entirely valueless for the determination of the question, whether Dr. Cook had reached the Northpole.”

Today, a century ago, the long-anticipated official decision of the University of Copenhagen on the data submitted by Frederick Albert Cook to prove he had reached the North Pole on April 21, 1908, was released. It consisted of just 50 words:

“In accordance with this declaration of the expert Commission, the Konsistorium wishes to state, that the material which has beeen submitted the University for investigation, does not contain observations or information which could be considered to prove that Dr. Cook had reached the Northpole on his last polar trip.”

The New York Times headlined that Cook had no observations of his own and had used those manufactured by August Loose, even though the report explicitly stated that there were no observations whatsoever, but only results. If the Dunkle-Loose affair had been an attempt at entrapment, it had failed. But the lack of observations shocked Cook’s supporters almost as much as if he had used false data.

When the University was presented the actual notebook from which the submitted data had been copied, it did nothing to change the experts’ opinion. In fact, they hinted, the physical arrangement of the book led them to conclude that the narrative it contained was itself a fabrication. To make sure there would be no future embarrassment for Denmark, they secretly made a photographic copy of the entire book before returning it to Cook’s private secretary.

The official printed report of the University was more explicit: “There is in the documents submitted to us a not permissible lack of such guiding information which could show the probability that the mentioned astronomical observations had actually been undertaken; neither has the more practical side of the question, the sleigh trip, been described by such details which could help control the report. The commission is therefore of the opinion that there can not in the material which has been submitted to us for examination, be found any proof whatsoever of Dr. Cook having reached the Northpole.”

In the wake of the Copenhagen Decision, a shower of abuse descended on the doctor from all quarters. Editorials coast to coast called him Ananias, Munchausen, a “thimble-rigger,” a “contemptable cheat,” and a “monster of duplicity.” Some editors were more temperate, holding out hope that Cook had believed he had reached the Pole, but he had somehow been mistaken. The Newark Evening News commented:

“Whatever the future may bring forth is hidden, but now the popular decision must be that Dr. Cook is a faker of colossal assurance. If he did reach the pole, it is pitiatble that he should be so discredited. If he did not, it is pitiable that a man’s thirst for fame should drag him to such depths. If the first is true, he, largely by his won fault, is a terribly wronged man. The only other alternative is that he has shamefully wronged his Nation and the nation that trusted him.”

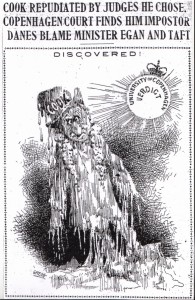

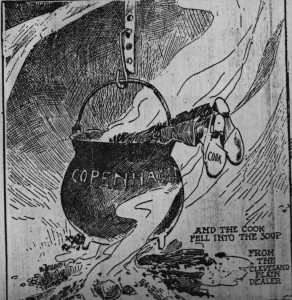

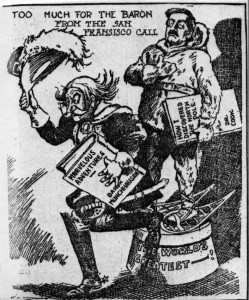

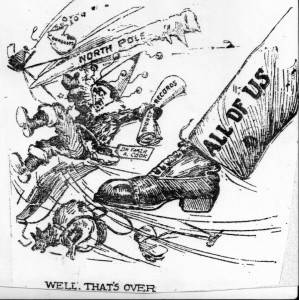

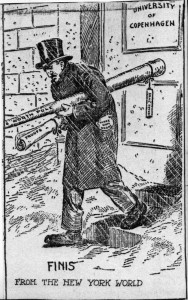

Editorial cartoonists had a field day at Cook’s expense. Here are a few examples of the many hundreds that were published:

In all of the outcry, only Cook’s voice was not heard. He had vanished completely, and no one seemed to know his whereabouts, or would for nearly another whole year.

Filed in: News.