The Cook-Peary Files: March 20, 1894: Dr. Cook makes an odd invitation

Written on February 17, 2020

This is the 15th in a series examining significant unpublished documents related to the Polar Controversy.

After returning from a privately financed excursion to the Arctic aboard the yacht Zeta in 1893, Dr. Frederick A. Cook conceived an American expedition to the Antarctic. At the time this was a novel idea, anticipating by four years an international push by European scientists to send out scientific expeditions to that practically unknown region.

To raise money to finance his scheme, Cook launched a series of lectures in which he exhibited two Labrador Inuit children, whom he had brought back to the United States with their parents permission, billing them as “wild Eskimos,” although their father lived in a log house and worked for Canada’s Hudson Bay Company.

When this effort fell short, he settled upon an arctic “tourist jaunt” to Greenland for the following summer. He sent out advertisements and broadsides to places likely to find takers, mostly Ivy League schools, where he succeeded in signing up a number of students and professors to see “Greenland’s Icy Mountains” at $500 a head. Five hundred dollars was no small amount in 1894; it was equivalent to about $10,000 in today’s dollar’s buying power.

He also sent invitations to individuals who he thought might have the money and incentive to go along. Probably his most unusual solicitee was Matty Verhoeff of Louisville, Kentucky.

In 1891-92 Cook had served as the surgeon on Robert E. Peary’s North Greenland Expedition. Matty’s brother, John, had answered an ad Peary had placed for volunteers to go with him, was rejected because of his diminutive size, but changed Peary’s mind with an offer of putting up $2,000 toward the cost of the expedition in return for being signed on as its “mineralogist.

Verhoeff proved to be a problematic character, who came to resent both Peary and his wife, Josephine, who went along with her husband. Just before the expedition was to return, he disappeared. After a thorough search, Peary concluded that Verhoeff had met with a fatal accident while crossing a glacier on his way back to Redcliff House, the expedition’s winter quarters. However, there were indications that Verhoeff had intentionally separated himself from the expedition, and might still be alive, and was hiding out somewhere until the rest of Peary’s party sailed home.

After Peary’s return to Philadelphia in 1892, Matty Verhoeff angrily confronted him about her brother’s loss, and accused him of abandoning him in the Arctic. Peary told her that John was most probably dead, but that he would look for him when he returned to Greenland the next year. His subsequent inquiries among the natives were negative as to his whereabouts; Verhoeff had never been seen again, and Peary sent word with his expedition’s returning ship to that effect. Peary named the glacier on which John met his fate the “Verhoeff Glacier.”

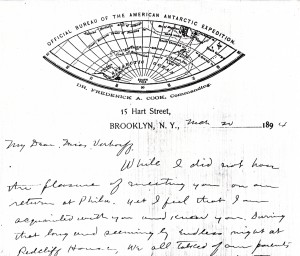

Cook knew of Verhoeff’s $2,000 payment to Peary and of his sister’s belief that her brother might still be alive somewhere in Greenland. On March 20, 1894, he sent this letter to her on the letter paper of his proposed “American Antarctic Expedition”:

My Dear Miss Verhoeff,

While I did not have the pleasure of meeting you on our return to Phila. yet I feel that I am acquainted with you and know you. During that long and seemingly endless night at Redcliff House, we all talked of our parents, our brothers, sisters, & friends. Your brother was no exception to this rule. As I sit here now writing to you, much of our conversation of that Arctic night comes vividly before me even the very words we used in our debates.

Indeed it all seems like a dream when I think of how we almost unconsciously emerged from a “night without a day into a day without a night.”

I have studiously avoided giving a public opinion on Mr. Verhoeff’s disappearance, because until I heard form the present Peary party, I thought there was a chance of his being alive.

This chance is of course lessened by the adverse reports of the second Peary party. Certainly if he remained anywhere within range of the most northern Eskimos his whereabouts would be known. He could of course have avoided them, but then his subsistence would be cut off. Without further discussing this question I herewith enclose you a circular of an “Arctic Excursion” We shall spend much of our time in the Whale Sound region, McCormick Bay, Verhoeff Glacier, and perhaps further north. This expedition is open to a few ladies and if you think the trip of sufficient interest, I should be glad to have you accompany us.

May I hear from you at an early date on this trip.

Yours very truly

F.A. Cook M.D.

Actually, there is no evidence that any other “ladies” were solicited. Everyone of his paying passengers was male, and it is curious that he made such an offer to a woman at all. He knew that she had gotten little satisfaction from Peary, who was sure her brother was dead, and when Peary’s ship in 1893 returned without finding him, this seemed to confirm it. But he also remembered Verhoeff’s $2,000.

The trip she missed aboard the steamer Miranda was a famous Arctic disaster. The ship first hit an iceberg and had to return to Newfoundland for repairs, then ultimately sunk in Davis Strait after ripping out her bottom on hidden rocks on the coast of Greenland. The party was carried home on a Gloucester fishing schooner in very tight quarters. However, there was no loss of life, and the “survivors” subsequently formed the Arctic Club of America, which eventually merged into The Explorers Club.

For details of this expedition and the convoluted reasons why John Verhoeff met his tragic fate, which are quite unexpected, see Cook and Peary, the Polar Controversy, Resolved, Chapters 8 and 27.

The original Cook letter is among the Verhoeff papers held at the Filson Club, in Louisville, KY.

Filed in: Uncategorized.