The Cook-Peary files: October 15, 1909: The Parker-Browne testimony, part 3

June 29, 2018

This is the 9th in a series examining significant unpublished documents related to the Polar Controversy.

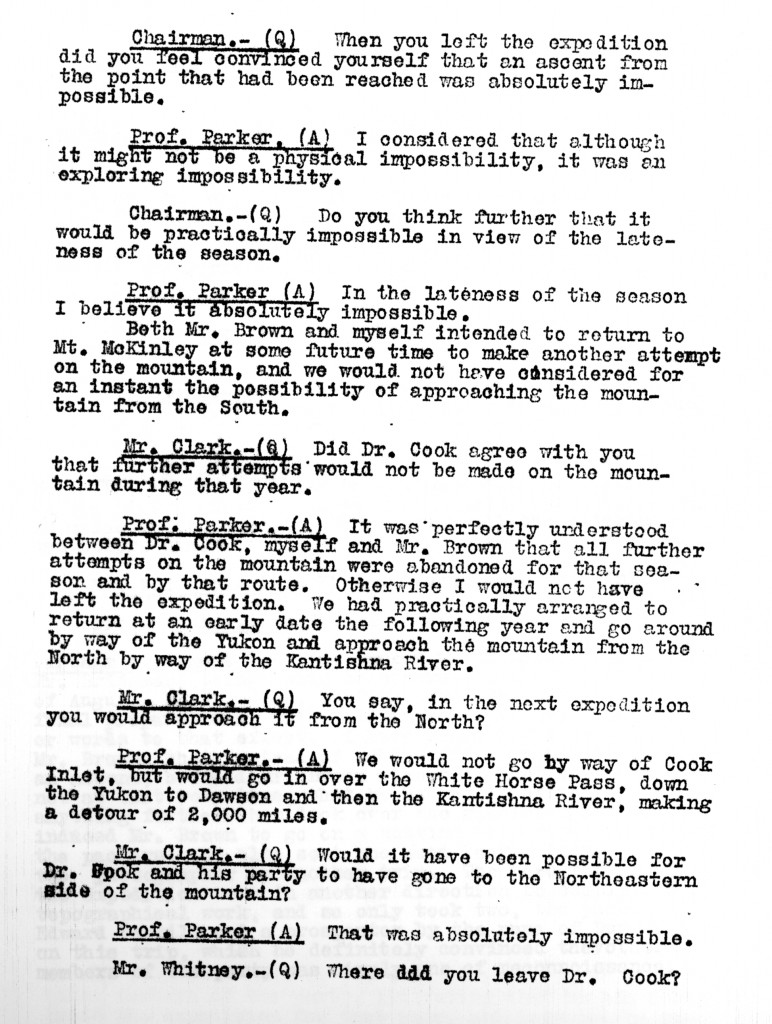

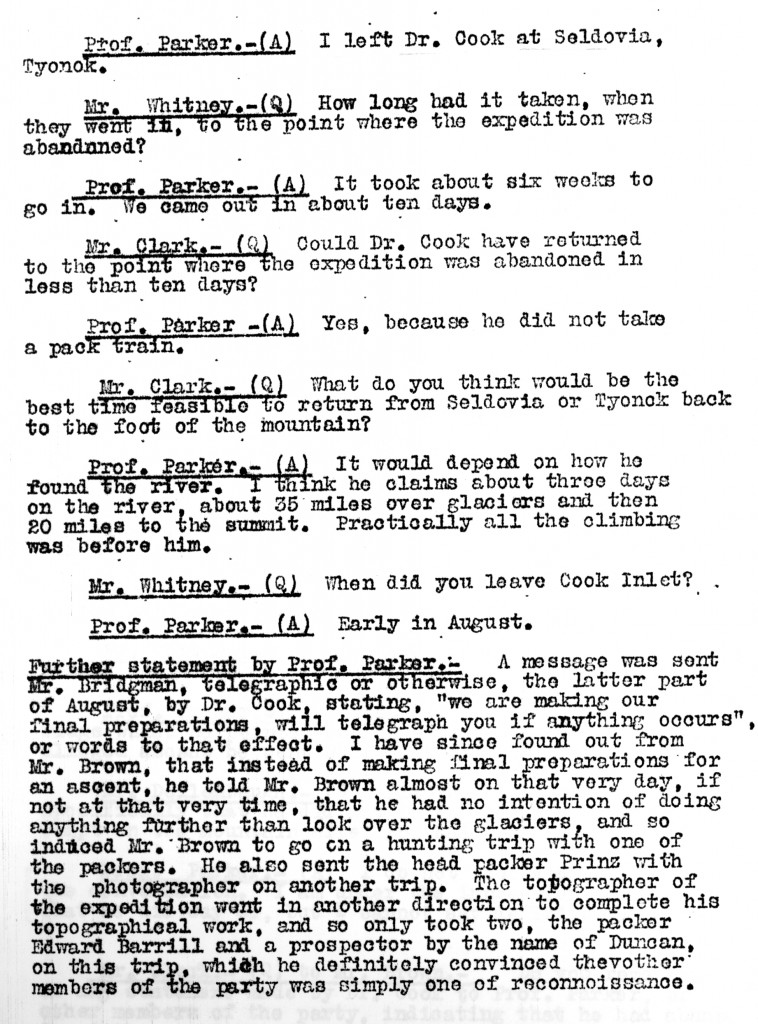

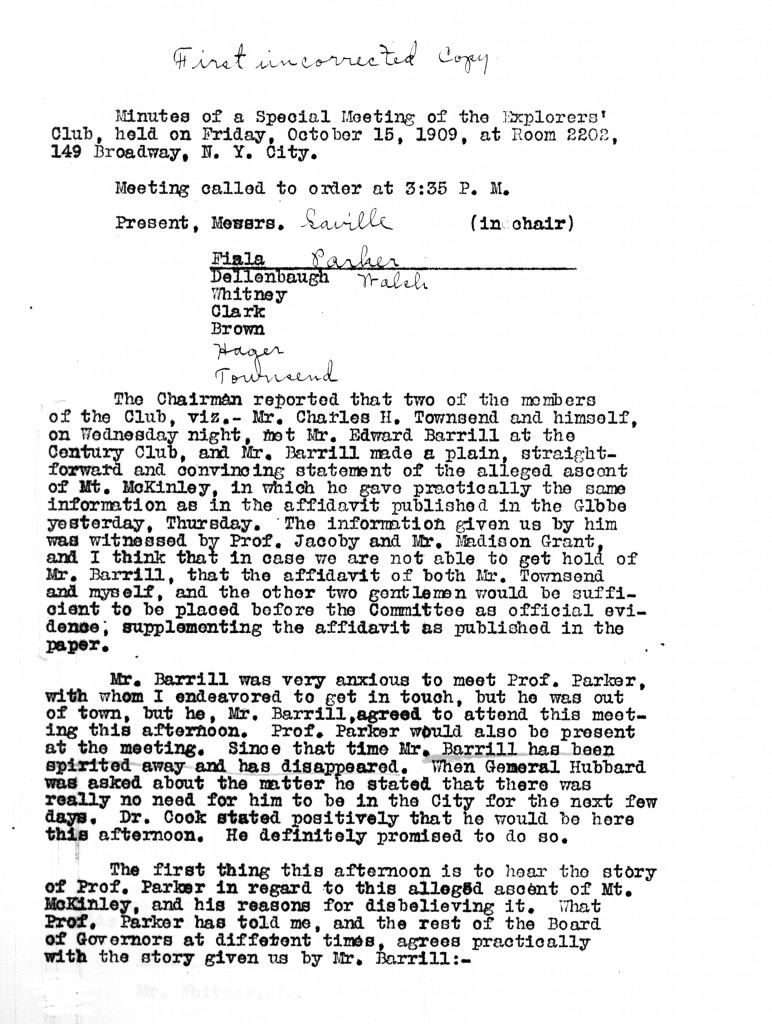

This post concludes the publication of the Parker-Browne testimony before the Explorers Club committee investigating the authenticity of Cook’s claim to have climbed Mt. McKinley in 1906. For the previous posts on this subject, see below. Comments about the content of Browne’s testimony are interspersed between the reproductions of the typed minutes of the session.

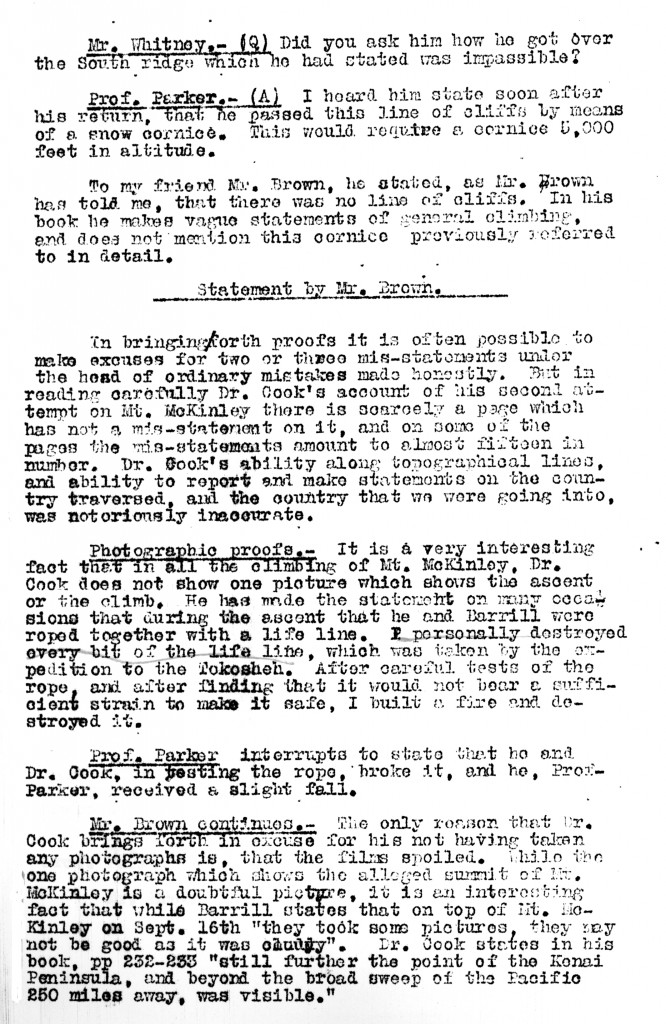

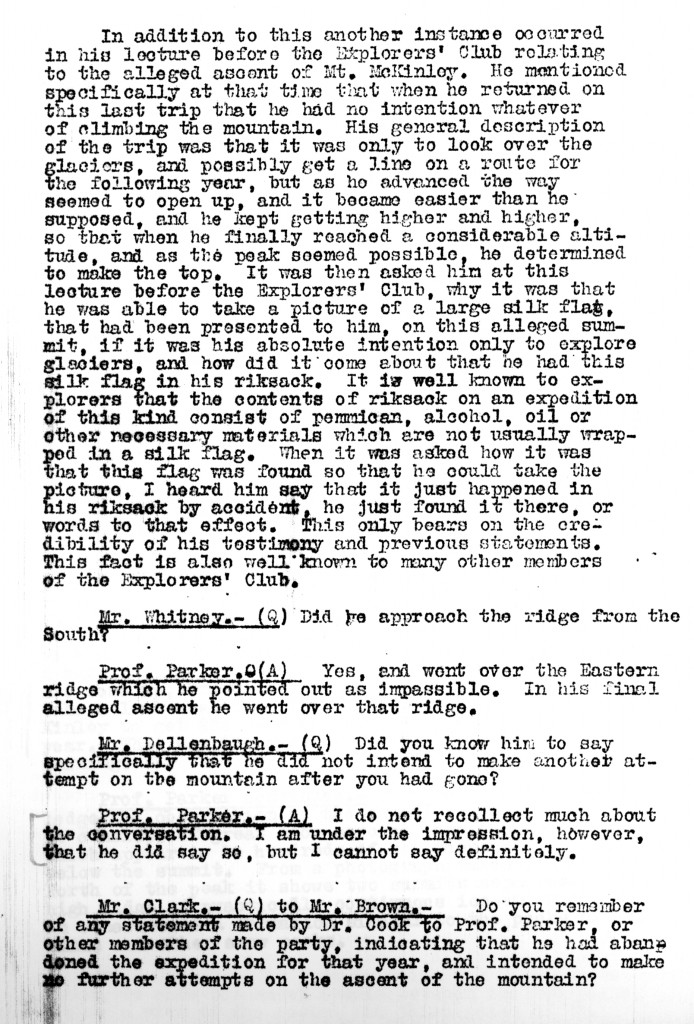

Parker’s final contention that Cook stated he got around the “impassible” cliffs they observed while camped on a peak along Ruth Glacier on a snow cornice, but does not mention such a cornice in his book, is untrue. In his book on the climb, Cook states that their route took them “up the knife edge of the north arête, around a great spur, from cornice to cornice, cresting sheer cliffs over which there was a sickening drop of ten thousand feet.”

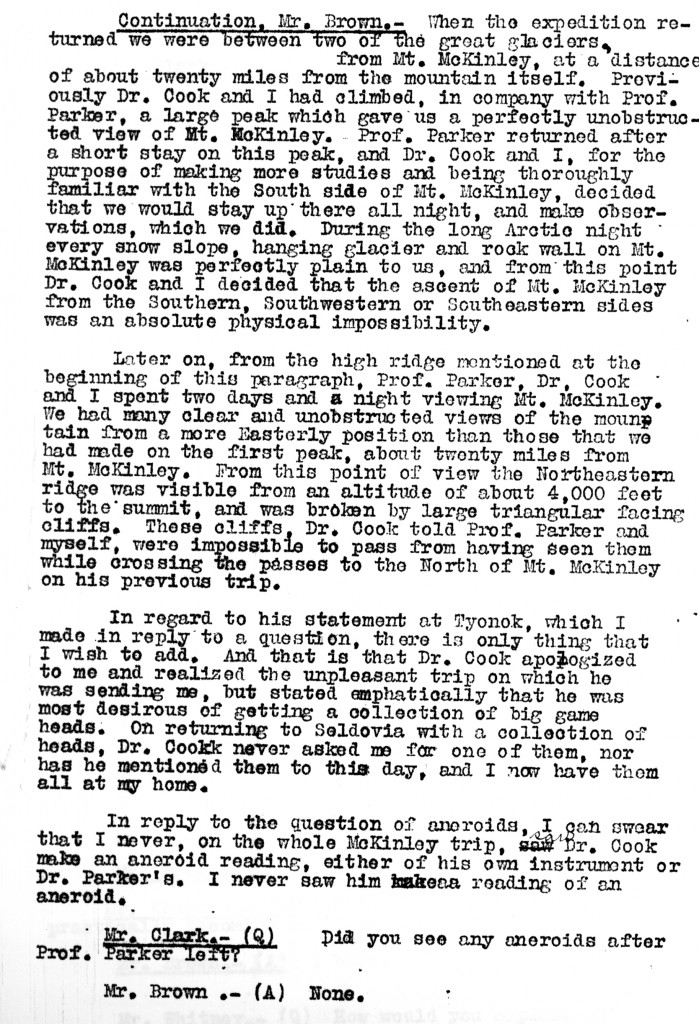

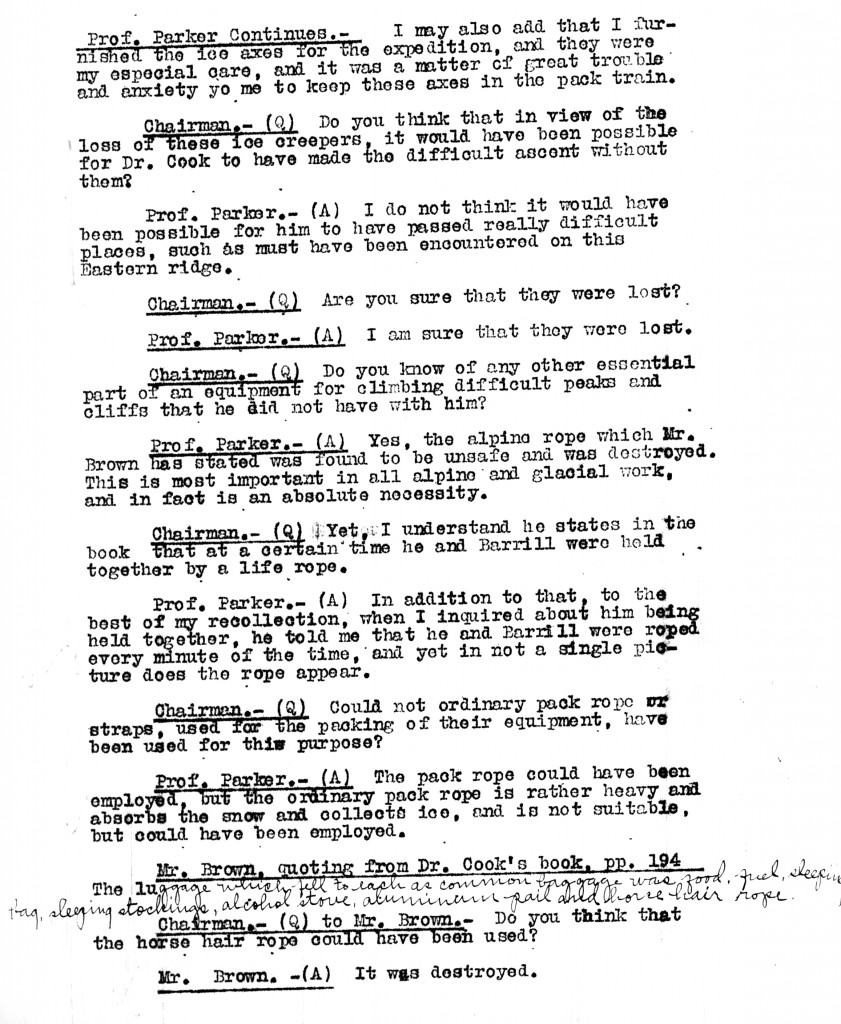

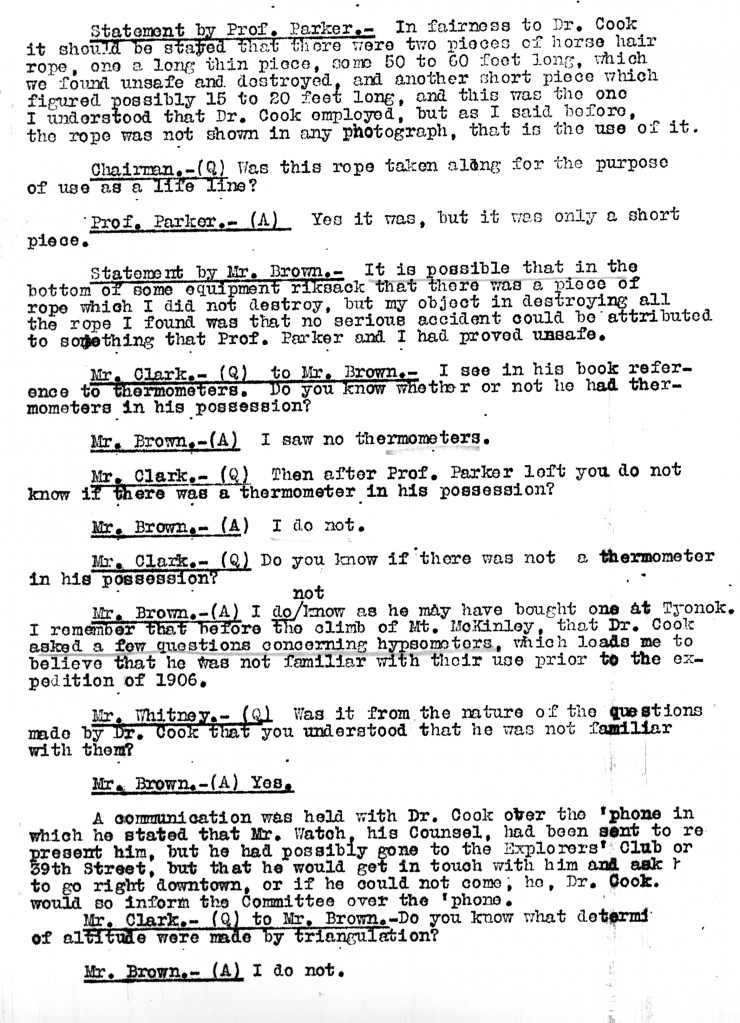

After Parker had finished his own testimony, Belmore Browne had his turn. In many respects he echoed or repeated Parker’s “evidence”: he emphasized what he considered Cook’s suspicious behavior in going off alone with Barrill after he had “assured” Parker that he would make no further attempt to climb the mountain that season, and also that Cook sent him on a hunt to obtain trophy heads, only to never once ask for them once he returned; he cast doubt that Cook was properly equipped to make the ascent, having no safety line or ice creepers, all of the rope, Browne testified, having been burned by he and Parker after the silk climbing rope had failed during a test of its strength, and the ice creepers having been lost; and he laid great importance, as Parker had, on Cook not having the instruments necessary to measure the height of the mountain, even if he did climb it.

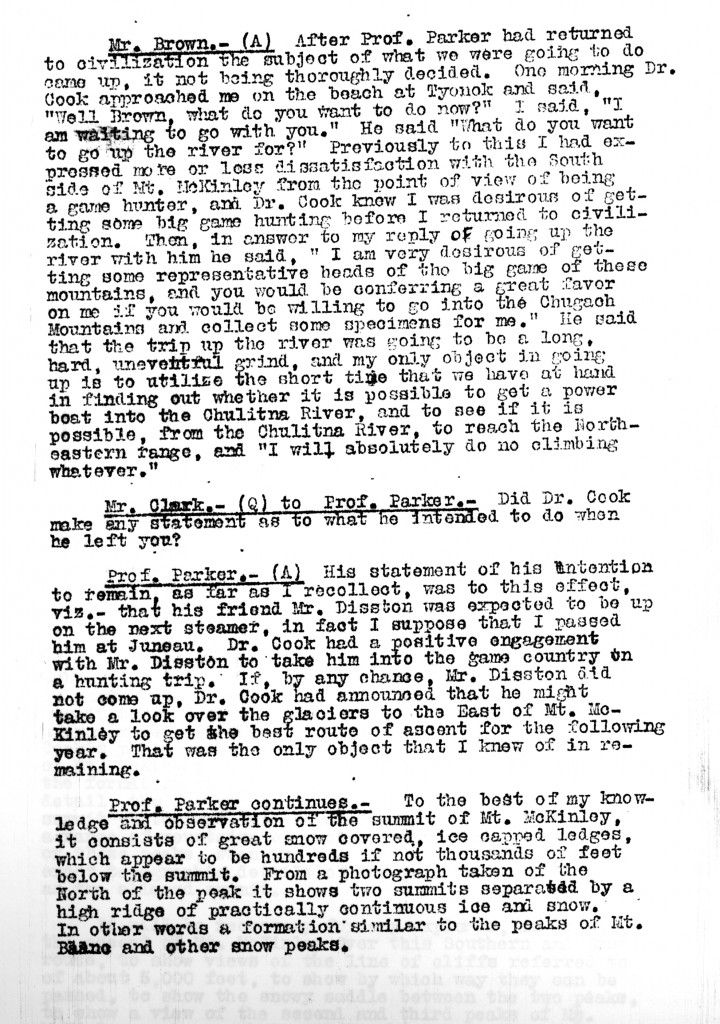

But in all these respects, as Parker’s before him, Browne’s testimony failed to establish any of these doubts as undisputed fact, and in some respects Browne was clearly mistaken. In Browne’s 1913 book, he stated that in Cook’s telegram to Herbert Bridgman, sent before he started for the mountain with Barrill, that he was preparing to make “a last, desperate attack on Mount McKinley,” when the actual telegram read: “We are now arranging our final efforts, and I hope to wire you from Seward about our work in early October.” As to his equipment, Cook lists it in his book, To the Top of the Continent, and never claimed to have a hypsometer or ice creepers (he used no creepers in 1903, but was able to ascend to about 11,000 feet on McKinley’s North Face and return safely), but that he took along a “horsehair lariat,” which could only mean the pack rope, as a lifeline. Browne, like Parker, insists that there was no one to read the barometer at a known location so that he could compare and correct his own readings of a barometer during the climb to determine the mountain’s height. Cook gave just those instructions to John Dokkin, who during the climb was at the location they left their boat, at an elevation of about 1,000 feet. In Cook’s diary, he states that he did have in his possession several aneroids, including one with a scale adjustment for reading heights over 16,000 feet.

As to the Barrill affidavit, which Browne states he believes “absolutely,” it seems clear that neither he nor Parker at the time of their testimony, and for a significant time after, did not understand the route described by Barrill in that sworn statement. As late as early 1910 they published a map that mislocates the “Fake Peak” entirely, placing it on the west side of Ruth Glacier (see the map published at page 494 of Cook and Peary). It seems that they only completely understood the route described by Barrill when they went over the same ground later that year for themselves. Even then, there was an element of chance in their finding the location of the place Cook took his famous “summit” picture. Indeed, Claude Rusk, who was on the same ground as Browne, was unable to find it at all, and misidentified the peak he thought it was taken from, even though he had access to both Barrill’s affidavit and diary and Cook’s published photos, just as Browne did.

Some additional elements of Browne’s testimony are noted below.

As to Cook’s observation of possible routes up McKinley, ironically, he had a very good view of the mountain from the top of the Fake Peak, and this, combined with his observations made three years previously through binoculars from the snout of Muldrow Glacier, probably served as the basis for the route he subsequently claimed. Unfortunately he seems to have failed to realize that the ridge he observed from each of these locations was not the same ridge, as he thought, but two different parallel ridges with a gulf between them, leading to many of the baffling statements he later published about his route up the “Northeast Ridge.” Here is the view he had of McKinley from Fake Peak from a larger photo now held by the Ohio State University Archives, and first published in DIO in 1997.

Browne’s criticism of Cook’s ability to describe terrain through which he had passed accurately is not justified. Cook’s descriptions in To the Top of the Continent are often uncannily accurate considering he is nearly universally believed to never have gotten past the Gateway to the Ruth amphitheater.

Browne’s statement regarding the route taken by Cook and Barrill from the fork at the Ruth Glacier’s amphitheater is interesting. Many have maintained that Cook never went beyond the campsite Barrill described them making at that location. However, Browne claims that Barrill told him after his return with Cook that they circled to the East, but that Cook said they went right over the summit of the ridge before them, that is, the East Ridge. Later Browne claimed that Barrill intimated to him that they had made no further effort to actually climb the mountain when he met with Browne on this occasion. Browne’s account of Barrill’s statement here seems to support that he and Cook went beyond the “Gateway” to the Ruth Amphitheater, which is also suggested by drawings in Barrill’s own diary.

There is considerable evidence by eyewitnesses, one a business partner of Barrill’s, that Barrill stated to a number of people that he actually made the climb with Cook and displayed his diary, which corroborates Cook’s account, as evidence that he did. The statements mentioned here are no more than third party hearsay.

The height of Mt. McKinley as determined by Russell Porter’s triangulations was almost identical the the height Cook published in his book. They were only off by a few feet of the actual height.

Cook’s lawyer’s name was H. Wellington Wack, not “Watch.” He did indeed go to the wrong place and so did not put in an appearance that day. Wack appeared with Cook at the club’s rooms at 11 AM on October 17, 1909, instead. Cook did not testify in detail before the committee at this time, pleading that he had no access to his diary of he 1906 expedition since 1908 and wasn’t even sure where it was. He asked for a delay to take care of his commitments for a lecture tour of the Western states and to put his records and photos in order before giving testimony to the committee. The committee agreed to grant him this respite, but he never fulfilled his agreement to lay the records before the committee, including his original diary and negatives of his Alaska photographs. Cook was dropped from the membership of the Explorers Club in December 1909, some said for his false claim of having climbed Mt. McKinley, others that he was dropped merely for “non-payment of dues.”

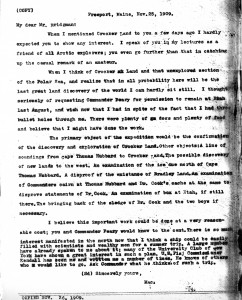

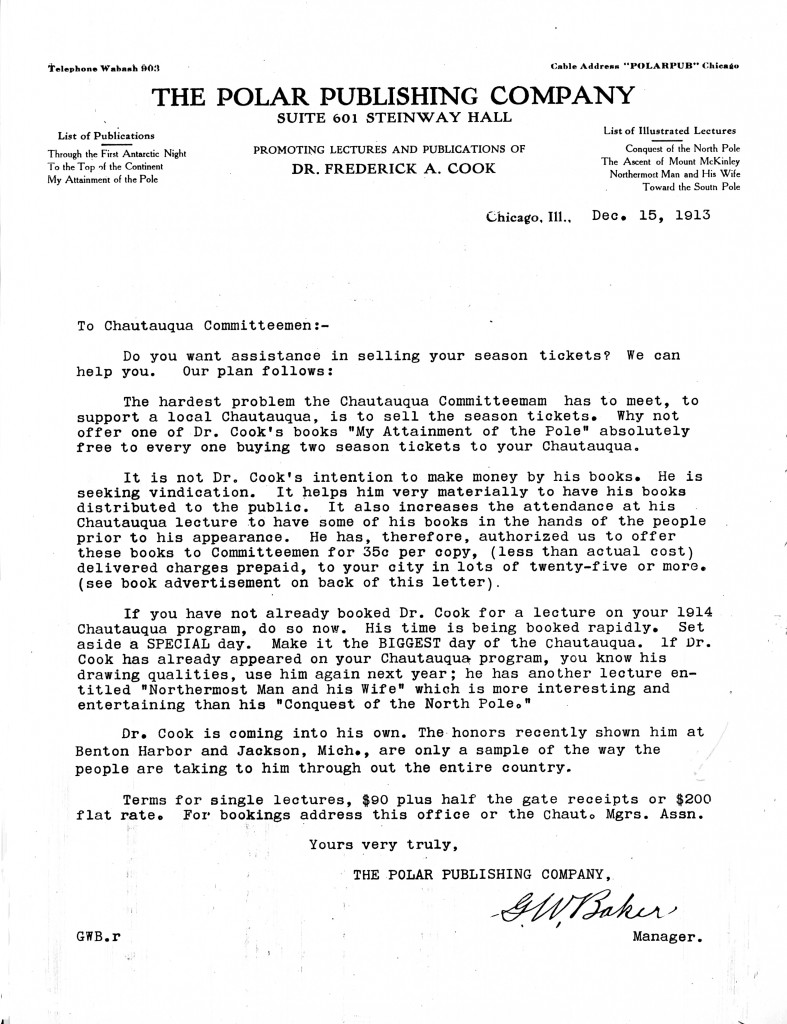

Baker’s letter is among the Peary Family Collection at the National Archives II in College Park, Md.

Baker’s letter is among the Peary Family Collection at the National Archives II in College Park, Md.

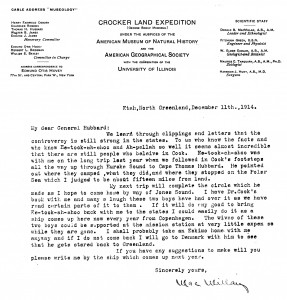

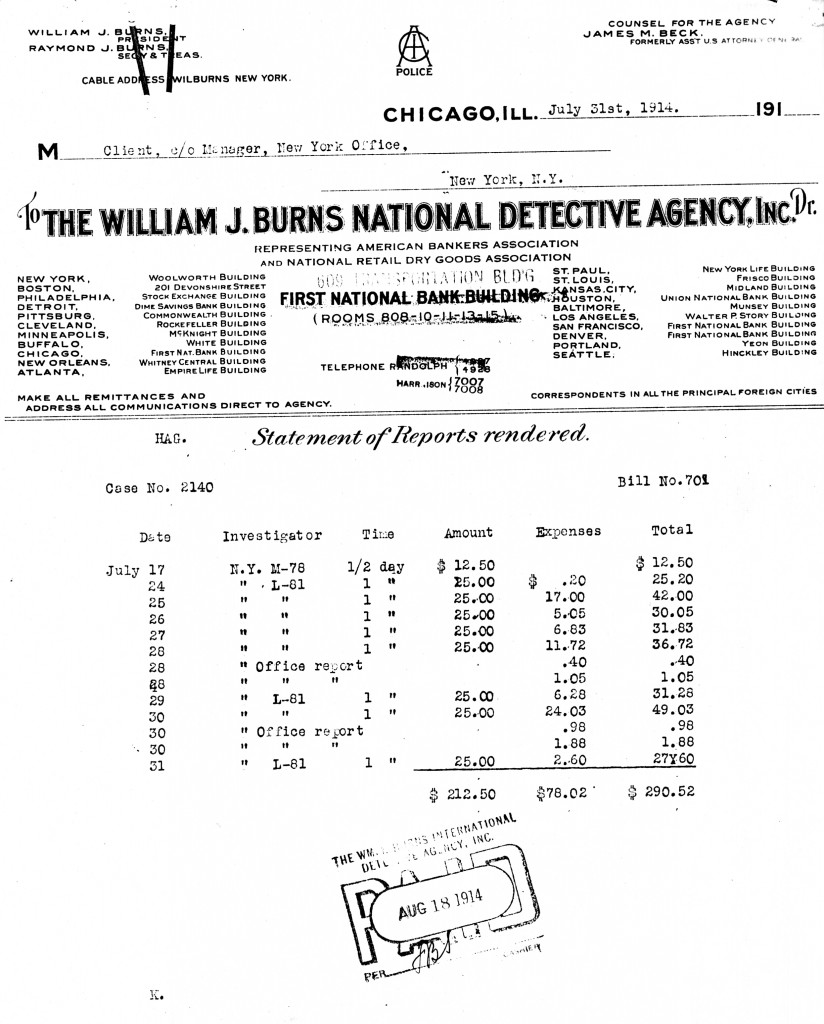

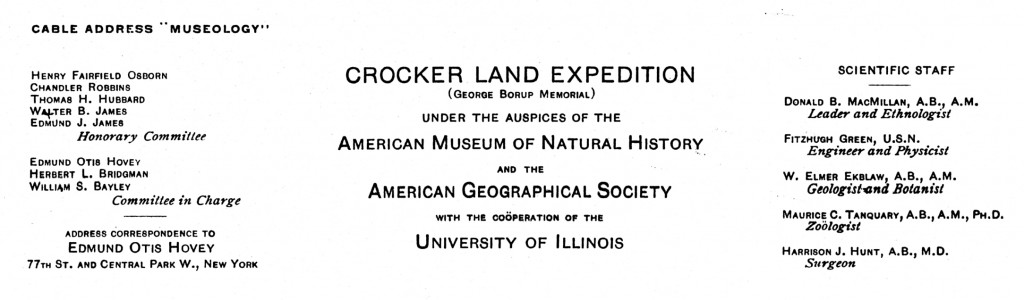

When the Crocker Land Expedition arrived in Greenland, the ship’s captain was unwilling to risk the crossing of Smith Sound to land the expedition near Bache Peninsula on Ellesmere Island, the preferred site of its winter headquarters. So Donald MacMillan was compelled to winter at Etah, site of a permanent Inuit settlement about 30 miles to the east in Greenland. After he proved that Peary’s Crocker Land didn’t exist in the spring of 1914, MacMillan settled in for his second winter there. He had not forgotten the other purposes he had outlined to Herbert Bridgman in 1909 (see previous post).

When the Crocker Land Expedition arrived in Greenland, the ship’s captain was unwilling to risk the crossing of Smith Sound to land the expedition near Bache Peninsula on Ellesmere Island, the preferred site of its winter headquarters. So Donald MacMillan was compelled to winter at Etah, site of a permanent Inuit settlement about 30 miles to the east in Greenland. After he proved that Peary’s Crocker Land didn’t exist in the spring of 1914, MacMillan settled in for his second winter there. He had not forgotten the other purposes he had outlined to Herbert Bridgman in 1909 (see previous post).