September 10 is a notable day in the history of the Polar Controversy.

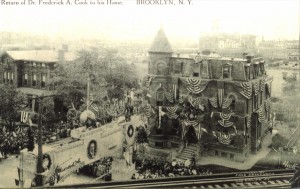

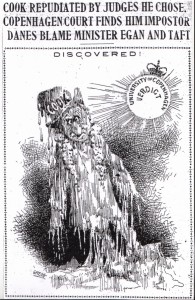

On that day in 1909, Dr. Frederick A. Cook, loaded down with nearly every honor the Danish nation could bestow, departed Copenhagen on the first leg of his journey back to America. The one exception was the exclusive Dannebrog, or Gold Medal of Merit, which it was rumored the Danish King withheld at the last moment when he heard that Cook had cheated one of his subjects of $500 in gold on an earlier visit to Greenland.

Meanwhile, Peary had reached the telegraph station in Labrador several days before and sent out his first messages. Among them were these:

COOK’S STORY SHOULD NOT BE TAKEN TOO SERIOUSLY. The Eskimos who accompanied him say that he went no distance north. He did not get out of sight of land. Other men of the tribe corroborate their statements. Kindly give this to all home and foreign news associations for the same wide distribution as Cook’s story.

Good morning. Delayed by gale. Don’t let Cook story worry you. Have him nailed. Bert.

But it was on this day a hundred years ago that Peary sent this famous message:

Battle Harbor Sept 10

Do not imagine Herald likely be imposed upon by Cook story, but for your information Cook has simply handed the public gold brick. He’s not been at the pole April 21, 1908, or any other time. The above statement is made advisedly and at the proper time will be backed by proof. Peary.

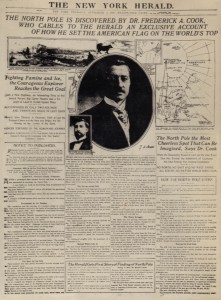

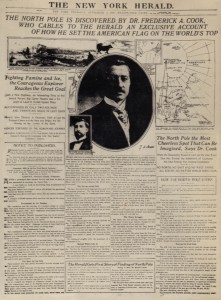

The New York Herald didn’t want to wait and instead asked for the “proof” immediately. After all, it had paid $3,000 to Cook for his exclusive account and had devoted it’s entire front page to Cook’s discovery only eight days before.

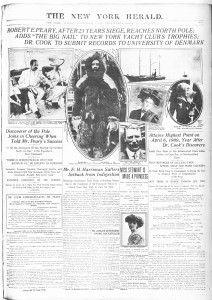

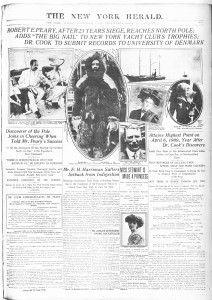

The Herald had given Peary similar coverage on September 7:

When “proof” was not forthcoming, Peary pleading that he had only seen “fragmentary” and “contradictory” reports of Cook’s claims, the Herald editorialized: “If the information he possess is too fragmentary and contradictory to permit of his controverting Dr. Cook’s story, it would have been, to say the least, more dignified to wait until he obtained the correct story before launching his charges.”

Ironically, in hurling his gold brick, Peary inevitably opened up his own unsupported claim to close scrutiny. As the doubts on both sides mounted, Governor Joseph Brown of Georgia, after noting the close similarity of both explorers’ stories, quipped, “If Cook has handed us a gold brick, Peary has handed us a paste diamond.” The governor’s words proved prophetic.

Did you know that Cook was a Democrat and Peary a Republican? No, really, it’s true.

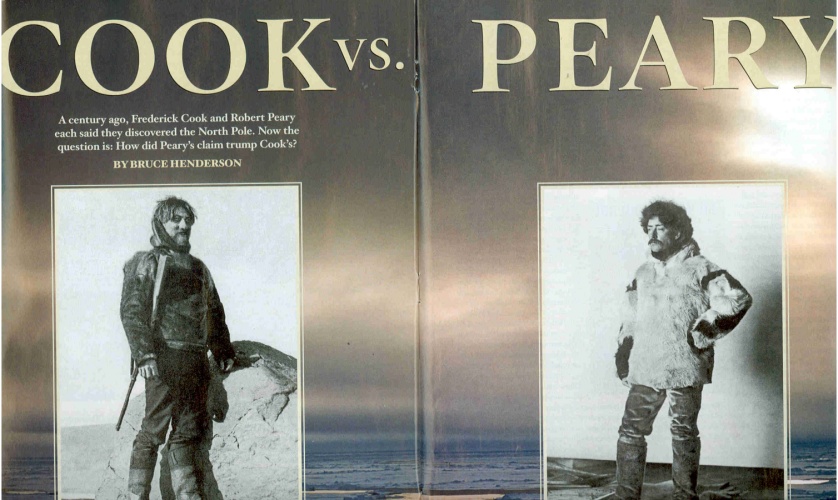

Now, John Tierney, the New York Times science writer, in his Findings column for September 8 and an additional post on his blog TierneyLab, recalls the dispute and the doubts, and then attempts to explain why each man had such devoted followers from the outset and why belief in the explorers’ claims lingers in a few even today. He compares them to political partisans, describing both groups as victims of what psychologists call “motivational reasoning.” Like the reality of Cook’s and Peary’s claim to the North Pole, he writes, it’s all in their heads and nowhere else.

Only a few blog comments show reasons unmotivated.

The comments sent to his blog posts seem to bear these comparisons out. There are several written by haters of “the establishment,” taking any excuse to call any symbol of it, in this case the symbol being the New York Times, to task. Many in the Polar Controversy were of a similar mindset and took their discontent out on Peary, seeing him as the establishment figure, and Cook as the little man being crushed in his big fight against it. There are a few sane comments, but as many of the posts are just disconnected ravings. Other comments address Tierney’s call for their candidate for the title of “Discoverer of the North Pole,” plugging their hero and proving Tierney’s point. He says one of he symptoms of motivational reasoning is that it allows its practitioners to “dispense with the facts” when confronted with evidence contradictory to what they wish to believe. A number of votes for Discoverer of the North Pole are for neither Cook nor Peary, but for Matt Henson, who accompanied Peary on his trek. These are perfectly willing to eliminate Peary, while dispensing with the obvious fact that if Peary was nowhere near the North Pole, then Henson could not have been near it either. That’s because Peary is said to have missed the Pole by at least 100 miles, and by their own individual accounts, the two men were never more than a few miles apart at any time. This is motivational reasoning at it’s finest. Yet, even though the reasoning is inexplicable, it is consistently predictable.

September 9, 2009: the Cook Society discovers the North Pole (blogs).

Predictable too is that the usual suspects will put in an appearance, sooner or later. Yesterday the Frederick A. Cook Society finally discovered the North Pole blogs and chimed in:

Why have “researchers” like Rawlins and Bryce ignored the field work and scholarship of the Russians of the last 30 or more years? One group–the Shapros [sic] have gone to the Pole on the ice cover and have followed Cook’s route up

McKinley

They have written books with English translation printings and participated in the Yale Club symposium of the Cook Centennial in May 2008 (ignored by the Times).

Motivated reasoning can be found where you look. I would love to have the same sociological journals examine Rawlins’ strange little mag, aptly called the Journal of Hysterical Astronomy, which expresses “a general disdain for those who do not agree with him” (Mr Bryce on Mr Rawlins).

— Russell W Gibbons

Gibbons is the Executive Director of the Frederick A. Cook Society, a small group of Cook family members and boosters dedicated to gaining “official recognition” for Cook’s claims through motivational reasoning. Although Gibbons’s comment is attached to the blog post concerning the recovery of Cook’s telegram drafts, which mentions neither sociologists or Mr. Rawlins, it attempts to transfer the society’s characteristics to them and him.

Dispensing the facts.

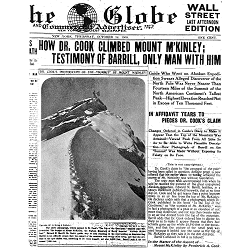

Why have researchers “ignored” the field work and scholarship he mentions? Because they were bought and paid for by the Frederick A. Cook Society. Members of that exclusive body are quick to point out that the sworn statement of Cook’s climbing partner that he and Cook never climbed Mt. McKinley in 1906 is worthless because it was bought by Peary’s backers, but they won’t mention that they contributed to the “field work and scholarship” presented by Dmitry and Matvey the Shparo at several of their occasional get-togethers. Researchers know Peary’s backers gave Edward Barrill $1,500 for his “expenses” related to swearing out his affidavit against Cook. The check that paid him and others for testimony against Cook is still in Robert Peary’s papers at the National Archives II. Perhaps Mr. Gibbons will reveal just how much money from the trust fund controlled by the Frederick A. Cook Society went to the Shparos for the “field work” they did that they now say exonerates Cook, and how much more they paid to have them present a paper on what they found using the society’s “grant” to the self-same society, and which then appeared prominently in the Frederick A. Cook Society’s publications as evidence in Cook’s favor?

Gibbons claims the New York Times ignored their centennial gathering in New York City in 2008. Not so. On the contrary, the NYT was the only news source that noted it at all (see my blog entry for September 1, 2009 below). And it was not a “Yale Club symposium.” It was a Frederick A. Cook Society event for which they rented the Yale Club’s rooms, which you may do for your own event, if you wish. Renting prestigous-sounding venues for such meetings is a recurring MO. Just ask The Mountaineers, who are still denying that the society’s meeting held in their rented rooms to celebrate the 90th anniversary of the day Cook claimed he summited Mt. McKinley was an endorsement in any way by their orgainzation of Cook’s claim.

Honestly, when presented with new evidence and better data, sometimes you have to admit you were wrong.

As for Mr. Rawlins’s “strange little mag” anyone who wants to can examine it and judge for themselves if it is a serious publication, as Mr. Tierney’s blog has provided a link to its online version. The name of the journal is DIO; but it is occasionally published under the sub-title given by Gibbons. That’s a Rawlins joke, reserved for exposures of wildly aberrant scientific “findings,” “fieldwork” and “scholarship,” such as the Frederick A. Cook Society specializes in.

As to the quote from this author about Mr. Rawlins, that comes from my book, Cook and Peary, the Polar Controversy, Resolved, published in 1997. That was my opinion then. At that time, I had only data from Mr. Rawlins’s book, Peary at the North Pole: Fact or Fiction?, and two live appearances from which to make a judgment. Although I still think his style of rhetoric and individual sense of humor sometimes works against his message, and have often told him so, I now have known him for more than a decade and I have a different opinion of him. He is a very thoughtful person to whom Truth, whatever it is, means a lot, and because it does, he is one of the most honest persons I have ever known. He has even been known to admit that he was mistaken.

This change of view came with more evidence. But a change of view based on additional evidence will never come to some. Evidence, “the facts” and even Truth itself doesn’t matter and can’t phase the motivational reasoners of the Frederick A. Cook Society. To this day, 12 years after it was published, not one of its members has ever been able to contradict a single salient piece of the extensive documentary and circumstantial evidence presented in my book that shows, beyond a reasonable doubt, that their namesake never climbed Mt. McKinley or was ever within 400 miles of the North Pole.

Yet, as Mr. Tierney quotes, “There will be a Cook [and Peary, and Henson] party till the end of time.” Anything is believable if you suffer from “motivational reasoning” or unreasonable motivations.

A Busy Week

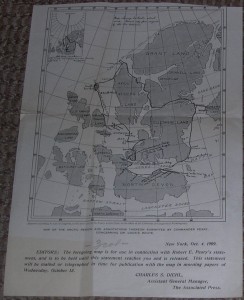

A Busy Week “Editors: The foregoing map is for use in connection with Robert E. Peary’s statement and it is to be held until this statement reaches you and is released. This statement will be mailed or telegraphed in time for publication with the map in morning papers of Wednesday, Oct. 13.”

“Editors: The foregoing map is for use in connection with Robert E. Peary’s statement and it is to be held until this statement reaches you and is released. This statement will be mailed or telegraphed in time for publication with the map in morning papers of Wednesday, Oct. 13.”

The scroll still exists and is on display at the Sullivan County Historical Society in Hurleyville, New York.

The scroll still exists and is on display at the Sullivan County Historical Society in Hurleyville, New York.