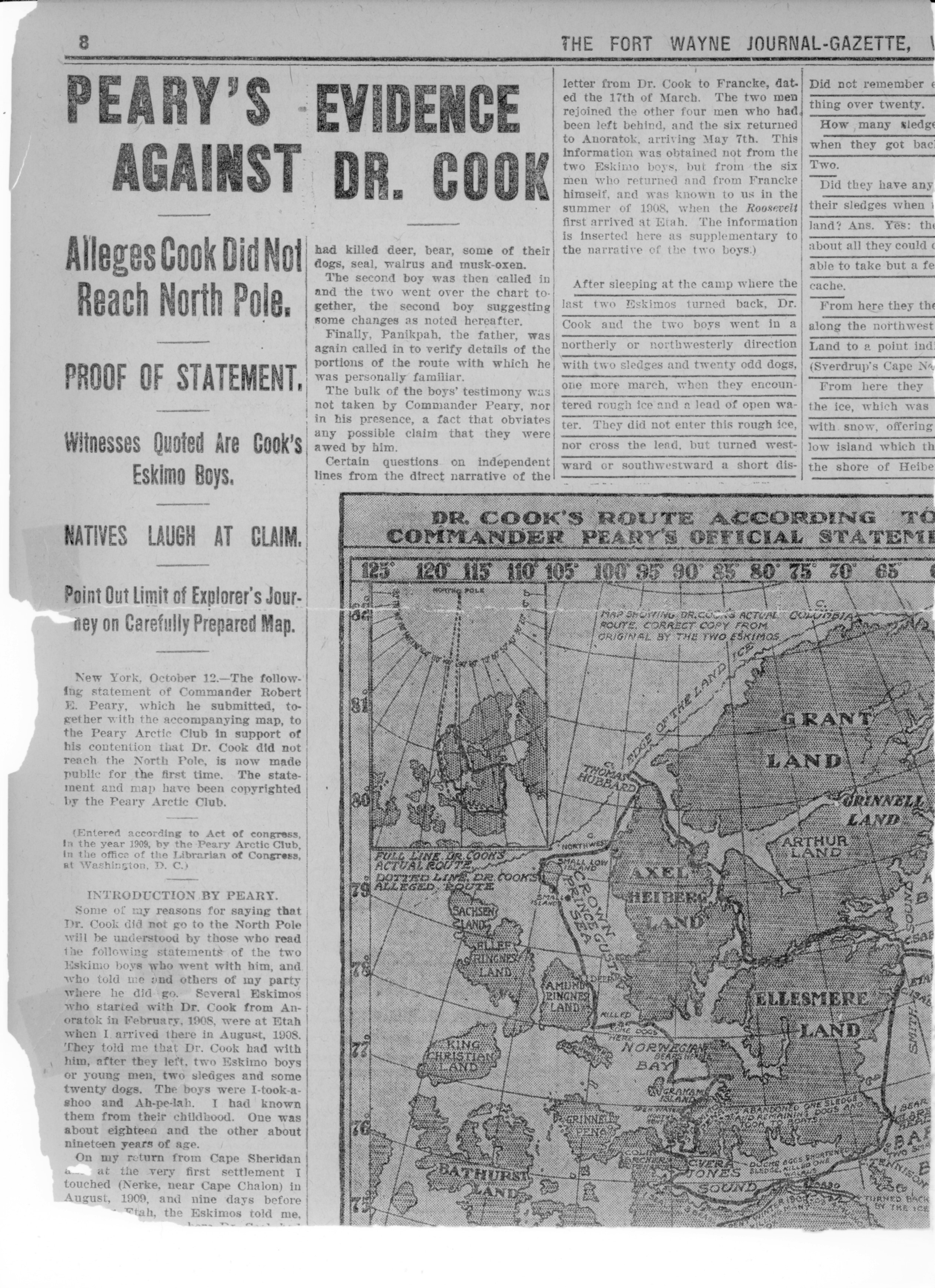

This is the latest in a series of posts that publish for the first time significant documents related to the Polar Controversy.

Since the original posting, I requested that the National Archives and Record Administration digitize the notebook in which George Borup wrote notes of the Inuit interviews conducted by Matt Henson in August 1909. I have now received that digital copy. I’ve requested that they post the entire digitized notebook on their website under record group XL. After examining the digitized copy in detail, I have revised the section of this post that deals with it. See the section on George Borup below.

In the last post we dealt with all of the eyewitnesses. The rest are only hearsay witnesses, but there were many of these in position to hear the Inuit gossip directly and what Cook’s two companions said of their journey through others. However, it should first be remembered that most of these had only scant knowledge of the native language and so could not get the story directly from Cook’s two companions or the tribesmen they may have told it to without an intermediary. What they heard must have come from someone who was fluent in the Inuit language.

Of Peary’s crew, including Peary himself, only Matt Henson would have had a level of understanding in Inuktitut that would enable him to grasp so complex a story as was related in the statement released by the Peary Arctic Club to the press on October 13, 1909. Of Peary’s assistants on the 1908 expedition, three, George Borup, Donald MacMillan and Dr. John Goodsell, had never been in the arctic before. Only Ross Marvin had been on a previous expedition with Peary, but he had been murdered by one of his Inuit companions between the time he left Peary’s party out on the sea ice and when the two Inuit companions in his support party reached land again. So the only statements of his knowledge of Dr. Cook’s movements were those previously reported (see the posts for the series “Inside the Peary Expedition” below). Marvin seems to have had a fair grasp of the native language, but after his death, as mentioned in the post on “Peary’s Proofs,” what Etukishuk and Ahwelah said was most likely given to Henson. But Henson was not functionally literate, and so could not write their story down himself. It appears that George Borup, and possibly Donald MacMillan as well, acted as scribes and took notes on what Henson said the Inuit said as they said it. Notes to this effect are among Peary’s papers in Borup’s hand, and the personalized language, using the first person singular, indicates that Borup is writing down Henson’s words, not his own. For instance, at one point the notes say that one of the Inuit “had been with me on the ice in 1906.” As just mentioned, neither Borup or MacMillan had been on the 1906 expedition, but Henson was.

But before we look at those crucial notes, let us examine the evidence that each of the other members of Peary’s crew left.

John Murphy

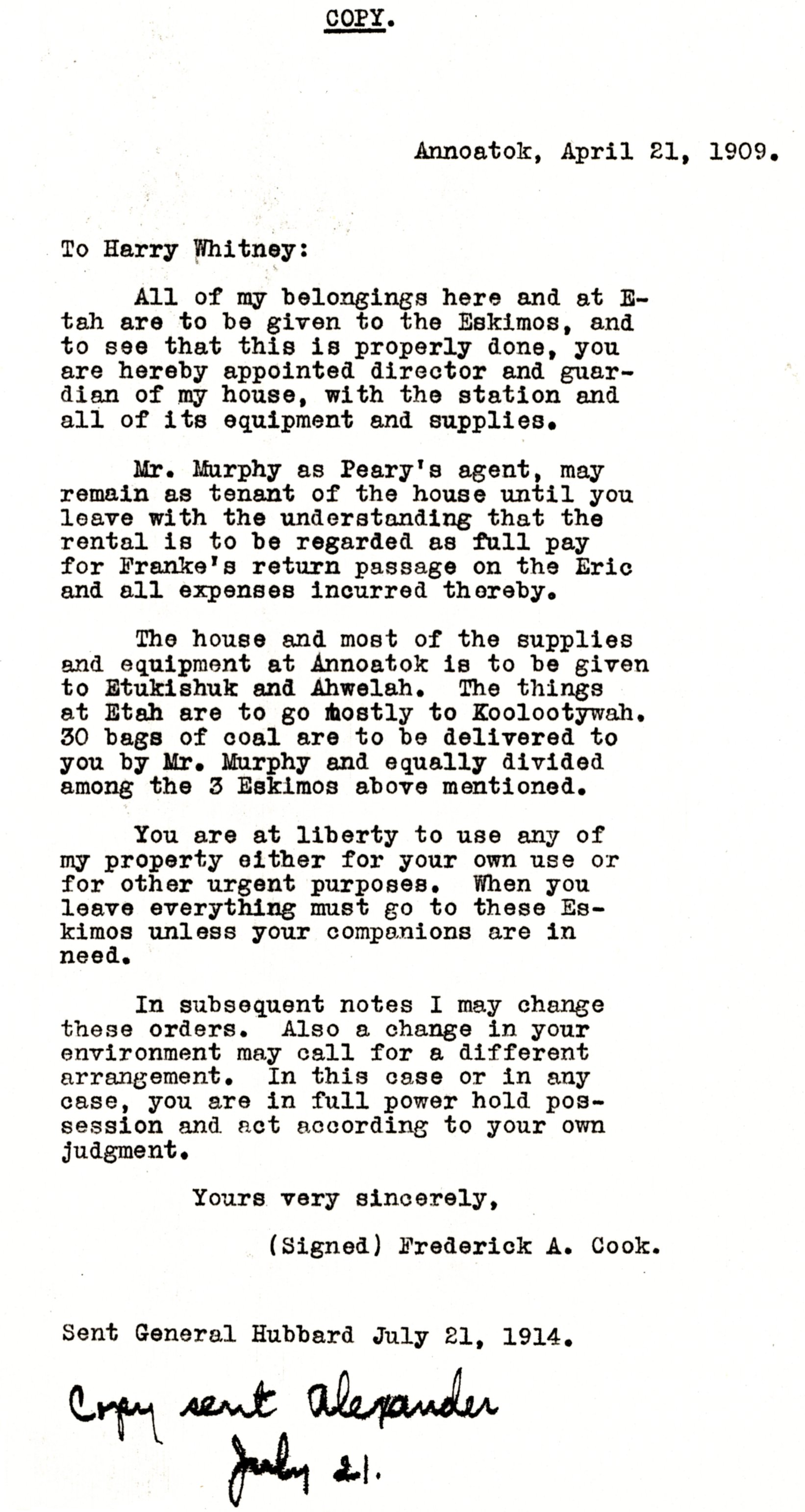

Murphy, as already noted, was the bo’sun of the Roosevelt. He, along with Billy Pritchard, the cabin boy, had been assigned by Peary to “guard” Cook’s supplies left at Annoatok, but had actually been instructed to trade them to the Inuit for valuable items such as furs and ivory. (see “Inside the Peary Expediton” below) The two of them split their time between Cook’s box house at Annoatok and the Inuit village of Etah, twenty-five miles down the coast. Shortly after Cook returned to Annoatok in April 1909, Murphy departed for Etah. He was not present at the time Cook told Whitney and Pritchard that he had reached the North Pole. Both Whitney and Pritchard kept their word to Cook not to tell of his attainment of the pole, so Murphy had no knowledge of it from them.

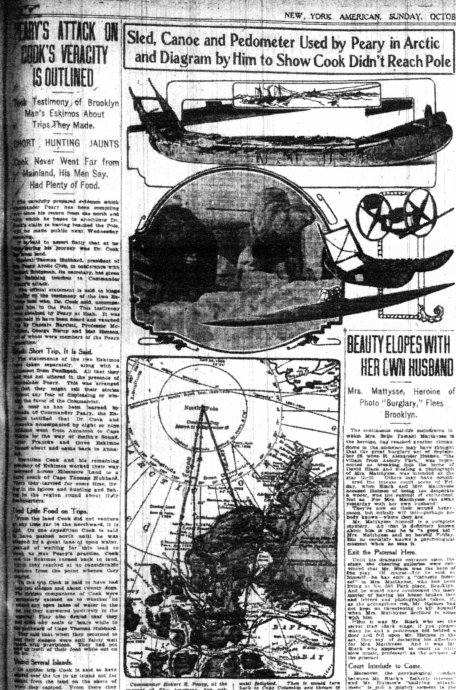

Murphy was perfectly illiterate. In fact, Billy Pritchard had been left by Peary to keep the log because of this. So he left no written account. The only statement attributed to Murphy on the subject was given in the New York American for October 7, 1909:

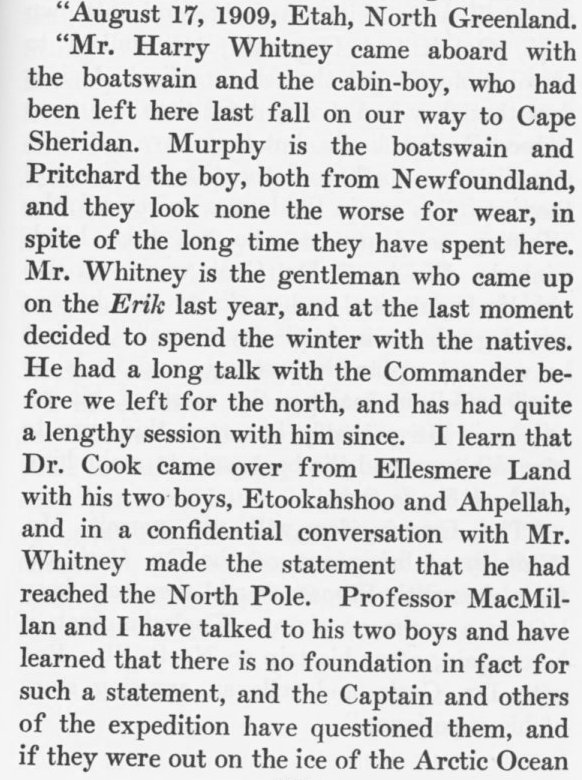

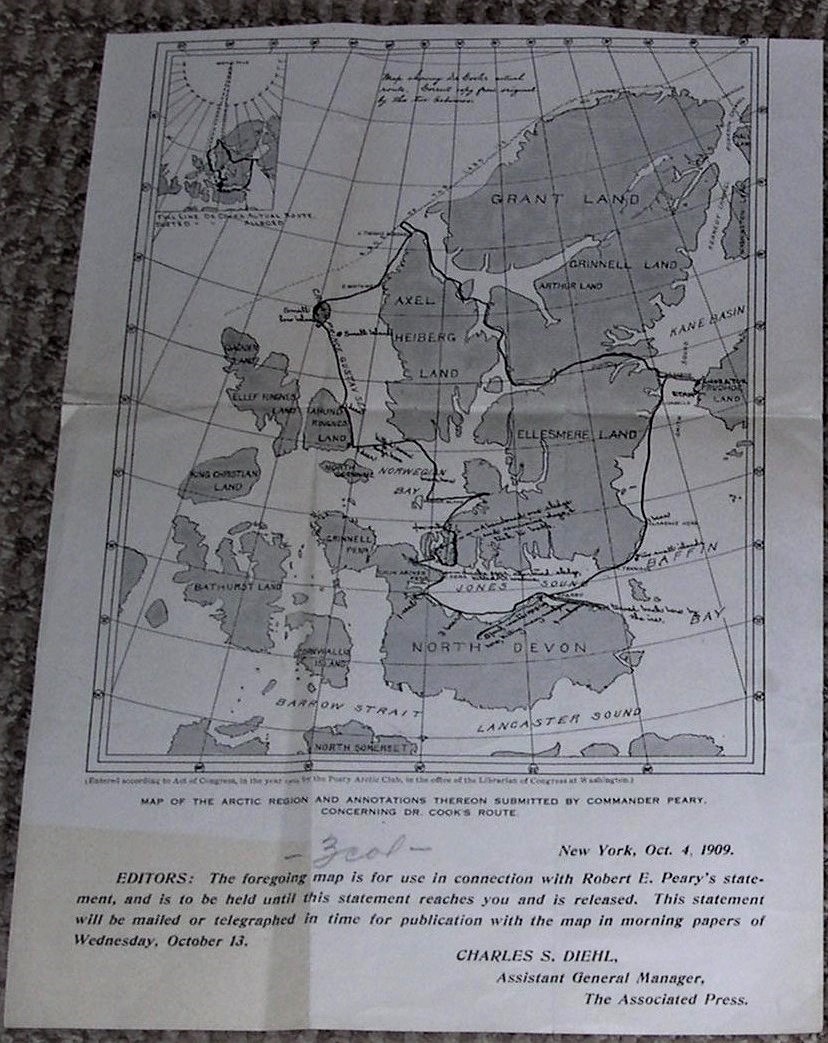

“The Commander,” says Murphy, “talks Eskimo like a native. And so does Henson. The Commander had Cook’s two ‘huskies’ on board and questioned them about where Cook had been. Now an Eskimo knows as much about a chart or a map as a passed mariner, and while they talked they took pencils and showed on the chart just where they had been with Cook. They say he made a two days’ journey toward the North and then stopped. At the end of the first day he had cached a heavy gun. At the end of the second day he ordered one of the huskies to go back and get that gun. Dr. Cook waited two days for the man to come up with the gun and then the three men turned westward, and that was AS FAR NORTH as they EVER GOT. The Commander has those marked charts now.”

Peary might have given the impression that he had mastered “Eskimo,” but in fact he only learned useful phrases that he could use to allow the Inuit to know what he wanted them to do, mostly commands. And the Inuit obeyed because they feared him greatly. Other than this, he relied on Henson as an interpreter. Clearly Murphy had heard the scuttlebutt about what Cook’s companions had told Henson, but even this short statement varies from Peary’s press statement. For instance, Murphy implies Cook camped four days on the ice before they turned westward, but Peary’s statement says he camped but two days.

Billy Pritchard

Peary had raised the point that Cook had told no one of his polar attainment upon his return as suspicious. Whitney had said nothing of it when he was aboard the Roosevelt, and neither had Pritchard. However, while Peary was in Labrador besieged by the press, a reporter got Pritchard to admit that he had known about Cook’s claim since April. This caused Peary to stop at St. Paul’s Island on his way to Sydney to get the full details being reported in the newspapers of what Pritchard said. Apparently, according to some accounts, the Inuit had told him that Cook had gone “way, way North.” After Pritchard’s statement became known, Murphy admitted that Cook had told him that he had gone farther north than Peary’s record in 1906—exactly what he had instructed Whitney and Pritchard to say.

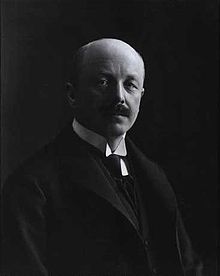

John Goodsell

Peary’s physician on the 1908 expedition was John Goodsell. He kept a meticulous diary daily that was extremely detailed, so detailed that Peary raided it for many of them to fill out his own published narrative, The North Pole. Here is what it had to say there relevant to Dr. Cook’s claim:

August 8, 1909

We hear that Dr. Cook returned to Annoatok this spring stopping but a few days before proceeding southward toward Upernavik.

August 25, 1909

We heard that Dr. Cook claims to have reached the Pole April 22, 1908. The Commander I believe received the information through a letter from Captain Adams.

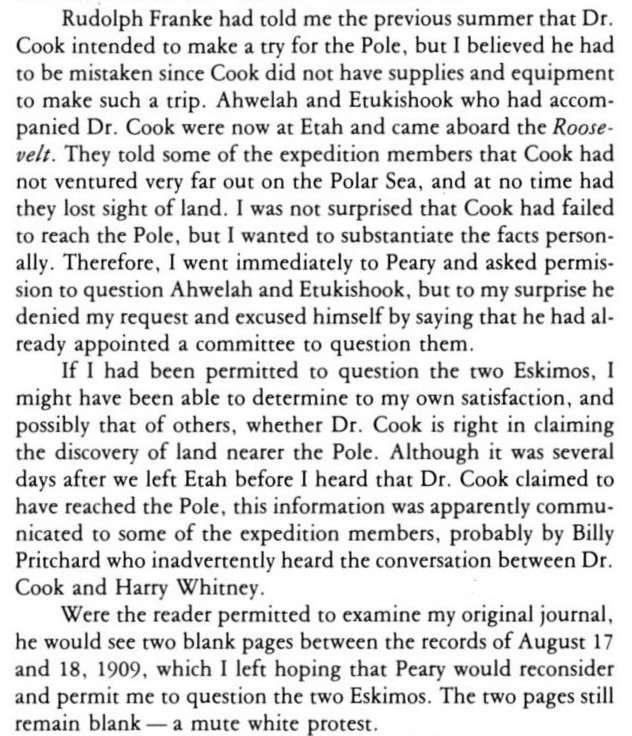

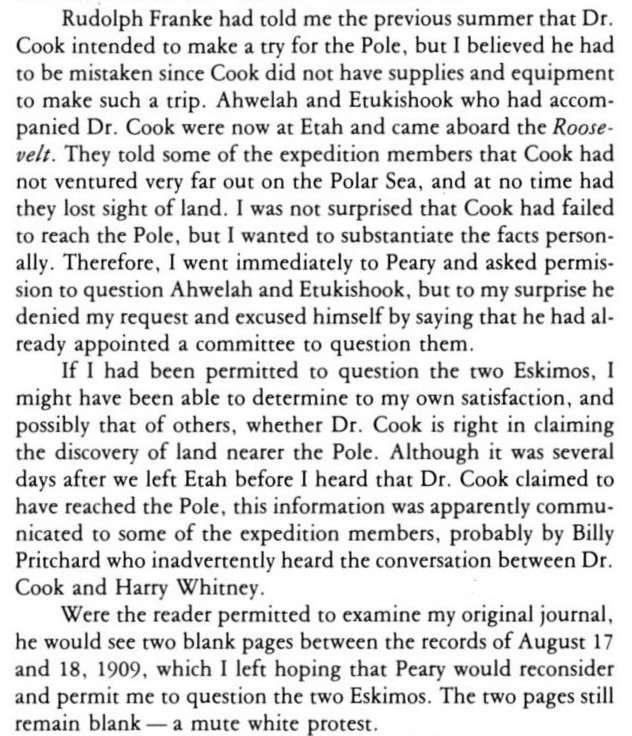

When he heard about Henson’s interview with the Cook Inuit, Goodsell requested permission from Peary to interview them himself so that he could include a record of what they said in his diary. Peary forbade him to do so. Consequently, there is not a word about it in his actual diary. Also, as a result of Peary’s denial of permission to allow him to independently confirm it, he refused to sign the alleged Inuit statement issued by Peary against Cook’s claim.

After his return, Goodsell, using his diary, wrote a book on his experiences in the Arctic which he called “There and Back Again.” Due to the fact that Peary had raided Goodsell’s diary so extensively for his own book, Peary used all kinds of delaying tactics to discourage the publication of Goodsell’s, including failing to return his manuscript for more than a year, which Goodsell had sent to Peary as a courtesy for him to read. By the time Goodsell regained his manuscript, publishers were no longer interested in his account, and it was never published. Only in 1983 was a heavily edited version of Goodsell’s book published under the title On Polar Trails. Here’s what it said relative to the subject at hand:

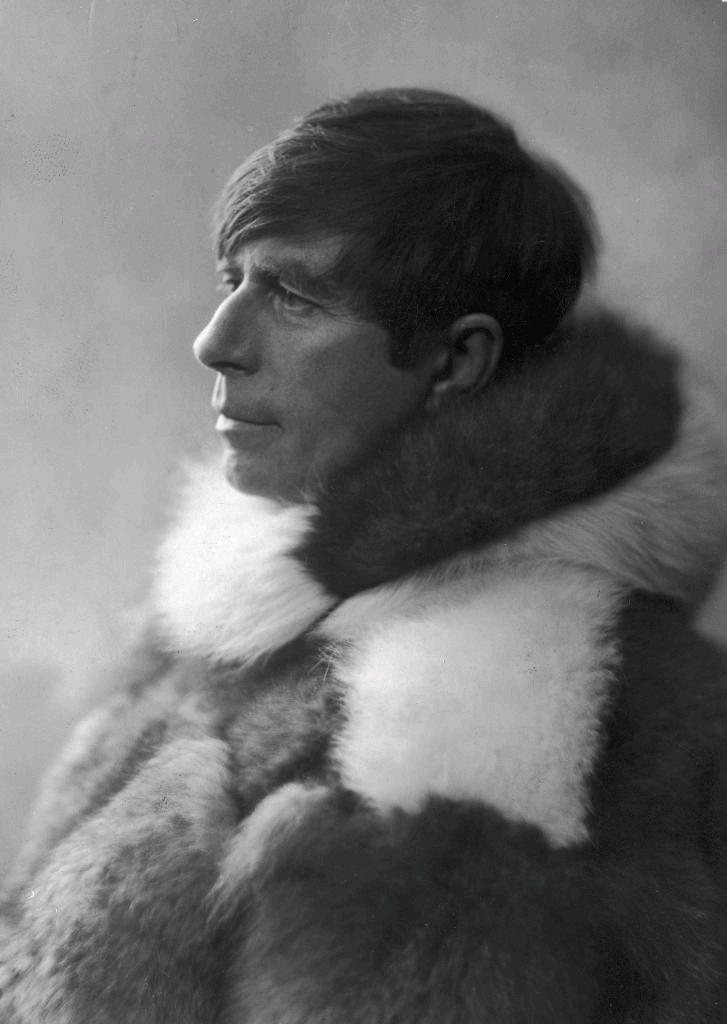

Matt Henson

Henson’s comments on the Inuit testimony are largely in the form of interviews published in the newspapers after the Roosevelt returned to civilization. One appeared in the New York World on September 22:

“[Dr. Cook] ordered [his Inuit] to say that they had been at the North Pole, [but] after I questioned them over and over again they confessed that they had not gone beyond the land ice.” In another interview he said, “It’s a joke to talk about Dr. Cook’s experience. He never had any experience with sea ice in his life. What the old man said about him in that book [Northward over the Great Ice] just meant that Dr. Cook was a good strong sort of a fellow to work around on land ice . . . . The old man has taught me to take observations almost as well as he can. I took a lot of them on our trip to the pole . . . The commander took me to the pole because I knew latitude and longitude so well and all about sea ice.” He then referred to Captain Adams’s letter to Peary: “The next day we got a box of letters at Cape York. That was the 25th [of August]. That’s when we found out that Dr. Cook said he had been at the North Pole. The captain of the whaler had written a letter to the Commander telling how he met Dr. Cook and Dr. Cook said he had been to the North Pole.”

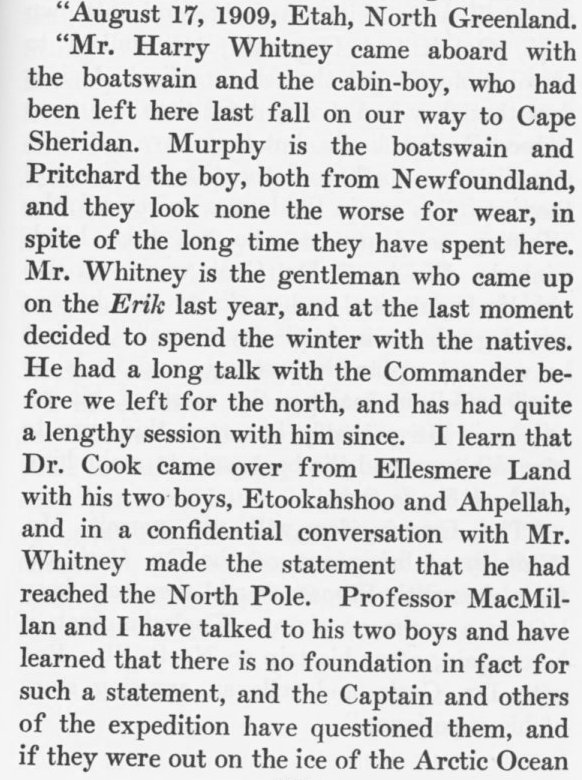

In his ghosted book, A Negro Explorer at the North Pole, Henson said, “At Nerke, just below Cape Chalon, we found the three Esquimo families . . . and it was from these people we first learned of Dr. Cook’s safe return from Ellesmere Land.” On August 17, the Roosevelt reached Etah. “At Etah there were two boys, Etookashoo and Ahpellah, boys about sixteen or seventeen years old, who had been with Dr. Cook for a year, or ever since he had crossed the channel to Ellesmere Land and returned again. These boys are the two he claims accompanied him to the North Pole. To us, up there at Etah, such a story was so ridiculous and absurd that we simply laughed at it . . . and the idea of his making such an astounding claim as having reached the Pole was so ludicrous that, after our laugh, we dropped the matter altogether.”

Henson then claims to “quote from my diary my impressions noted in regard to him”:

All of this proves how little we can trust Matt Henson’s reports. First off, as noted by Dr. Goodsell, definite word that Dr. Cook claimed he had been to the North Pole was not received until August 25, in the letter from Captain Adams. So Henson’s statement to have laughed at the “astounding claim as having reached the North Pole” on August 17 implies that Cook’s two “boys” must have told their tribesmen that Cook claimed to have reached it. He all but admits to this in the New York American interview, saying that Cook had “ordered” his Inuit to say he had been to the Pole, but after he badgered them, they “confessed” they had not been beyond the land ice. Yet he then goes on to say they only learned Cook was claiming the pole on August 25th. Yet in his book that claims it quotes from his “diary” entry for August 17, he says that he knew then that Cook was claiming the pole because he learned that Pritchard had revealed Cook’s confidential conversation with he and Whitney. It is very clear that Pritchard did not reveal what Cook had said until about September 20, well after the Roosevelt had reached Labrador.

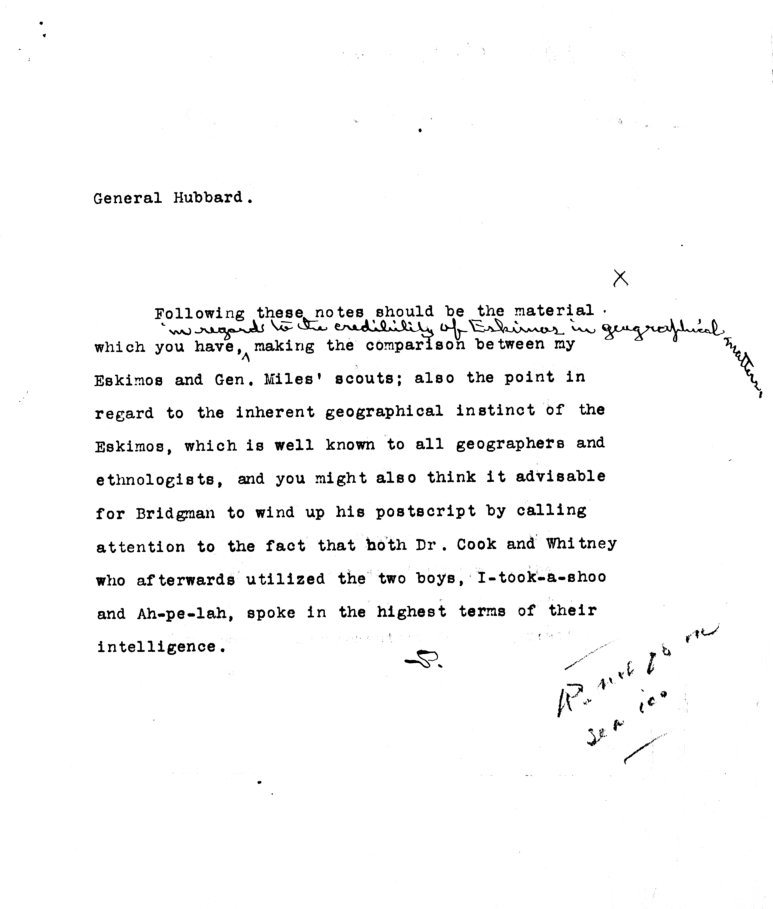

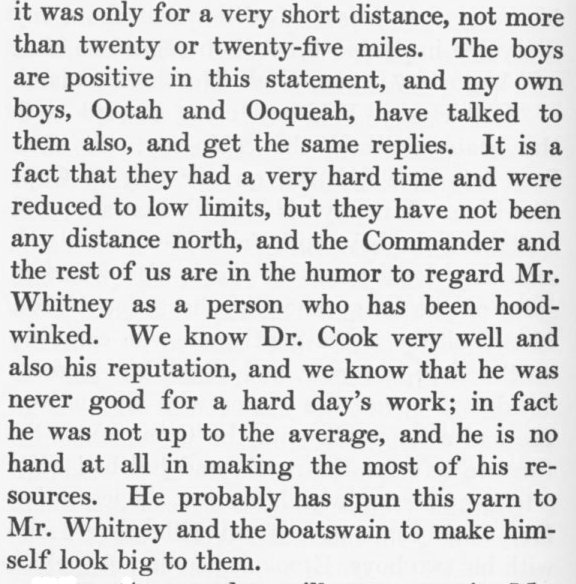

Other details bring into question Matt Henson’s general truthfulness. According to Dr. Thomas Dedrick’s diary of 1900, Henson could neither read nor write, nor do simple arithmetic. Dedrick prided himself on teaching him that winter. There is much evidence, however, that indicates that Henson never achieved full literacy, even later. Peary himself wrote definitively to General Thomas Hubbard in 1909 that Henson “can not take observations.” No diary of Henson’s from any of the Peary expeditions exists, even though Peary habitually kept at least copies of everyone else’s, so Henson’s quotations from his “diary” are no more than recollections, at best, fabrications at worst. This is shown by the so-called quotations from his diary here. For instance, he says that Whitney had told them that Cook was claiming to have reached the pole, when he did not. All of this, and much else in the record concerning Matt Henson tends to confirm Josephine Peary’s characterization of him in her 1891-92 diary as “a vainglorious braggart.” It should also be noted that Henson says that “if they went out on the ice of the Arctic Ocean, it was only for a very short distance, not more than twenty or twenty-five miles.” This was far more than Peary’s statement implied, or anyone else gave Cook credit for at the time of the controversy.

Captain Bob Bartlett

Bartlett, who had captained the Roosevelt for Peary previously in 1905-06, left a confusing record. The bulk of his papers are reported to be in his hometown of Brigus, Newfoundland. I have never seen any of these, but there are also some in the holdings of Bowdoin College in Maine. Although I had access to these, I did not encounter a diary of the 1908 expedition there or among Peary’s papers either. It might in fact be in one of these places, but I did not see it.

Bartlett, you might say, was Peary’s “Right-hand Man.” He was ever faithful to Peary and was the only member of the crew that Peary deigned to share any honors accruing from his false claim to have been at the North Pole in 1909. Bartlett went with Peary on his victory lap around Europe in 1910 and was awarded several silver medals, both there and in America, and he was co-signer of the British limited edition of Peary’s book, The North Pole.

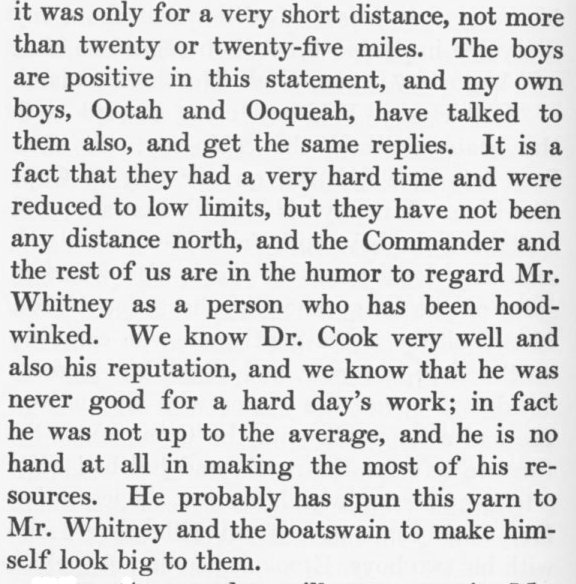

In the Philadelphia Record on October 1, 1909, appeared an interview Bartlett gave while off Sandy Hook. In it he asserted that Cook could not have reached the North Pole because “No man in this world can get Eskimos to go out of sight of land except Peary. . . . They wouldn’t budge unless the commander were there to push them.” Of Cook’s claim, Bartlett said, “While at Etah we didn’t hear that Cook had reached the Pole. There were rumors that he had been pretty far north, but we never took those reports seriously . . . . Recall the elaborate expeditions as Abruzzi’s and Nansen’s and others, including our own in the past–all these have failed. And yet two men and a sledge with two dogs, more or less, are said to have done it.”

Bartlett’s sycophantic attitude toward Peary is reflected in his long-after-the-fact account of the North Pole expedition published as The Log of Bob Bartlett in 1928. There are many Newfoundland fish stories in its pages, but the fishiest come in his chapter entitled “A World of Lunatics,” which addresses facets of the Polar Controversy. Although there is positive evidence (see above) of Peary first learning that Dr. Cook had claimed that he reached the North Pole on August 25, via Captain Adams letter, Bartlett claims that when they reached Battle Harbour, Labrador, in early September they were ignorant of his claim. He writes that Borup and MacMillan went ashore and returned with the news that Cook was claiming he got to the pole: “Quickly the meager details came out and in a few minutes the whole ship was buzzing with the astounding news,” he wrote. He says that only Peary took the news calmly, and then foists the blame for Peary’s intemperate telegram in which he accused Dr. Cook of “handing the world a gold brick” on George Borup, saying that in the heat of the moment he blurted this out in response to Cook’s “absurd” claim. Bartlett then relates that Peary used Borup’s expression in the telegram only reluctantly, and then only after no one on the entire ship could think of a more moderate synonym.

This is only one of several apologias for specific notorious actions by Peary during the controversy that Bartlett takes pains to excuse Peary for. Later in the chapter he spins the incredible tale that Peary believed he was sending his first account of his expedition to the New York Herald rather than the New York Times, when it was well known even before the Roosevelt left in 1908 that Peary had signed an agreement with the latter paper for the exclusive rights to his account. In a few words, the book’s account, whether through tricks of memory or the passage of time, is inaccurate, to give it the most charitable evaluation. As to the Inuit testimony, which Bartlett signed off on as a witness when it was released in October 1909, as did Borup, MacMillan and Henson, there is not a word.

George Borup

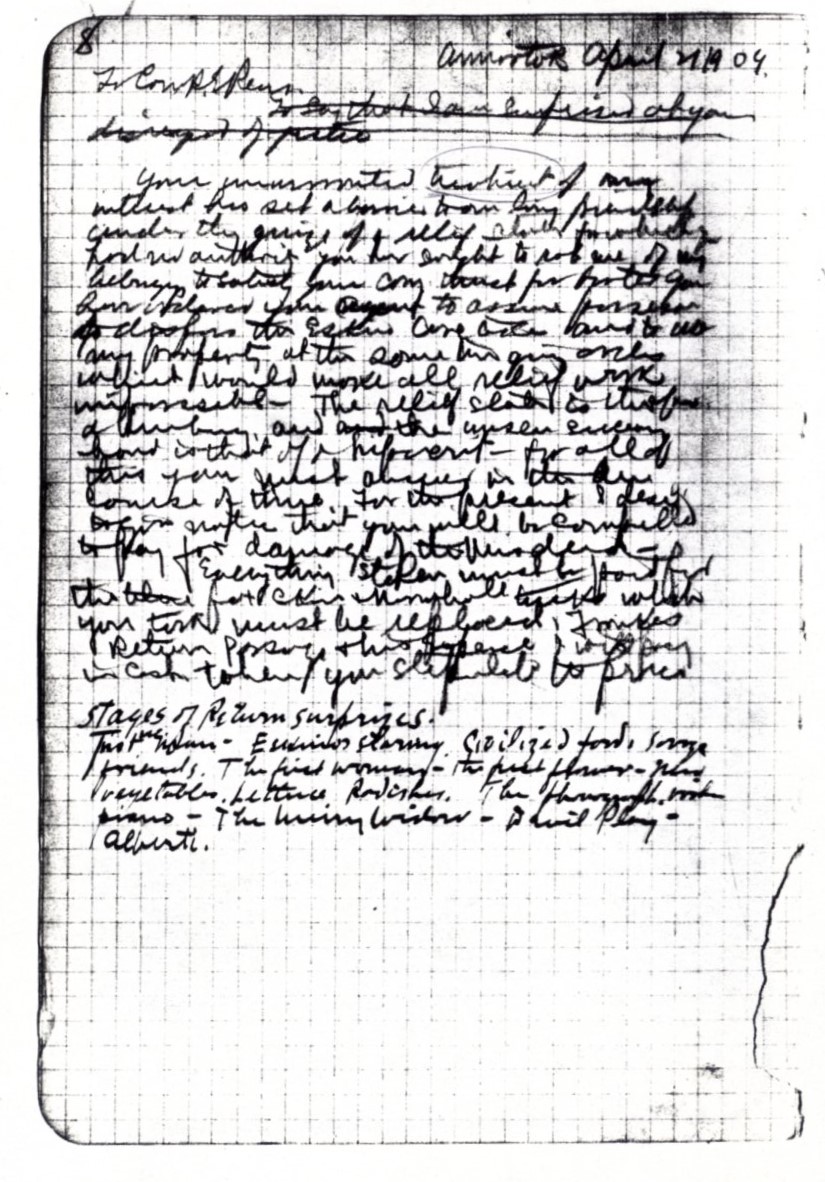

Among the most interesting evidence is that written in the hand of George Borup. It comes in the form of notes which, from their telegraphic phrasing and their character and content, suggest that they were taken down during, or rewritten shortly after, the interview of not only Etukishuk and Ahwelah, but several other Inuit who accompanied Cook to the tip of Axel Heiberg Island in 1908.

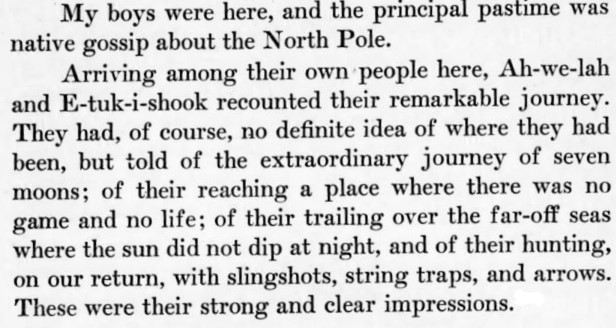

In his book, A Tenderfoot with Peary, Borup devoted only a single paragraph to the Inuit interview:

But he added, “Though my note-book has something more about our talk with the Eskimos, here’s where I quit.” Perhaps he “quit” because what it contains does not support this statement.

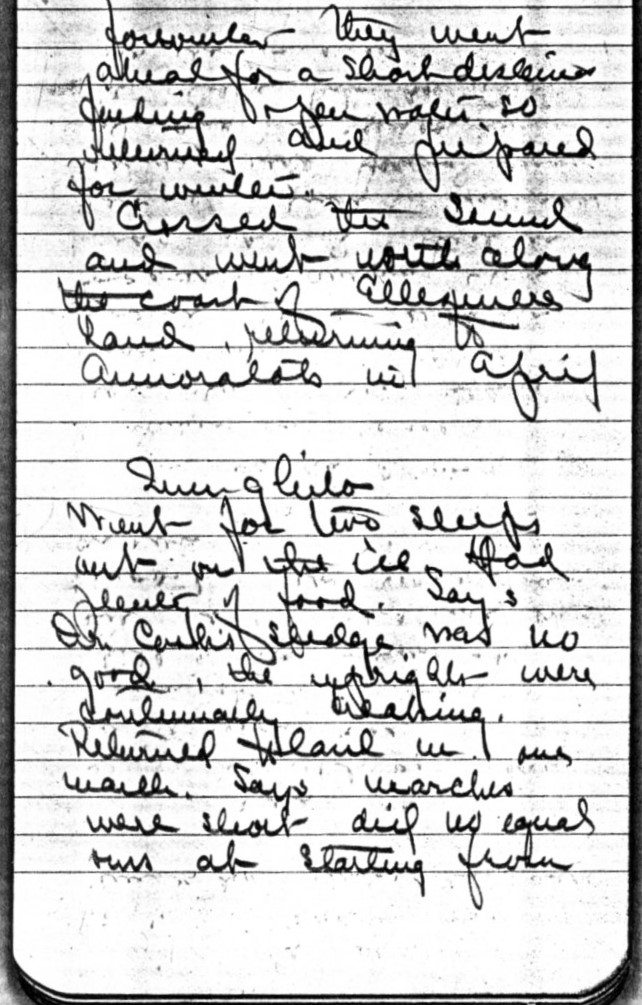

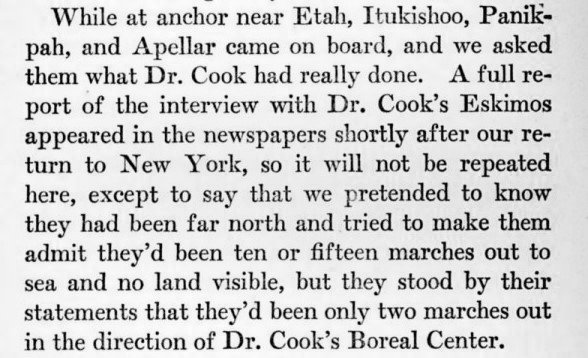

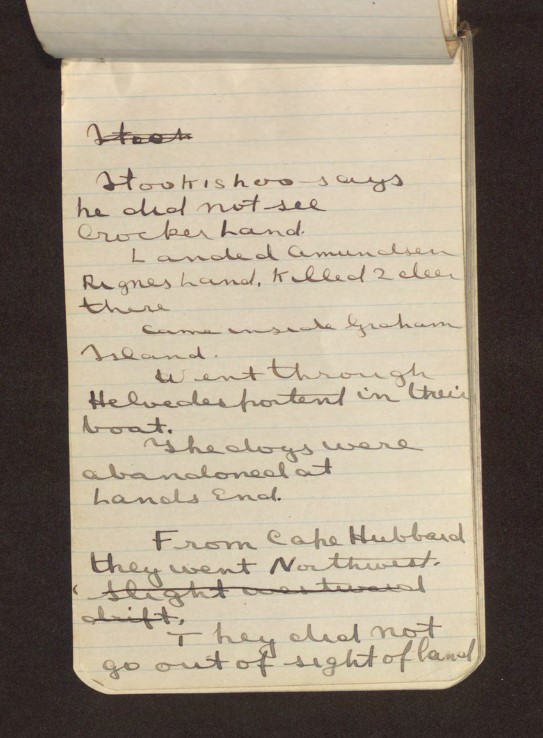

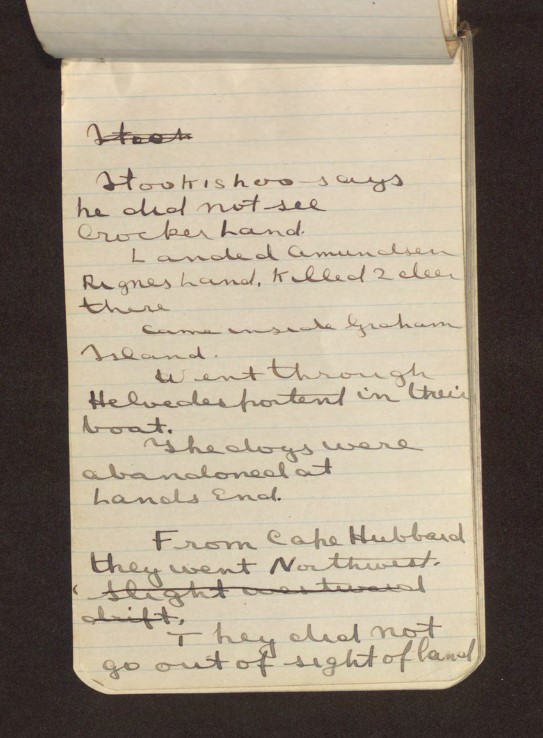

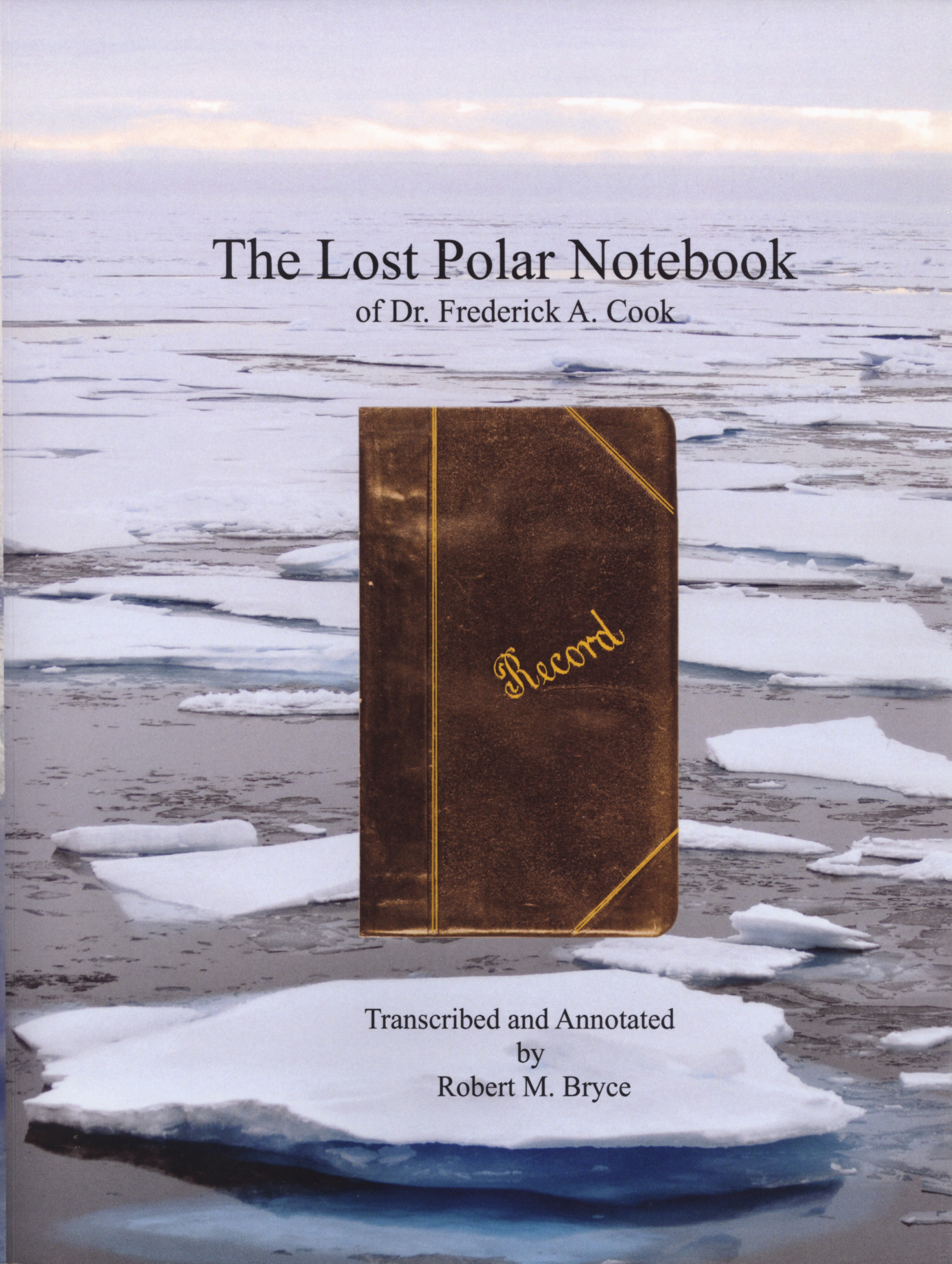

The notes, published here for the first time, are contained in a small pocket notebook bound at the top that is exactly like the one Peary kept his record of his alleged journey to the North Pole in 1909.

All entries are on the lower pages except for the insert noted below, which is on the upper page of the open pair. The ***** indicate a page change; all the deletions and inaccurate spellings of place names, grammatical errors, etc. are faithfully reproduced below. Words and comments in brackets have been added by me for clarity. Words in parentheses are part of the document. On the first page are several lines of shorthand written in pencil including the words “he has an ill feeling” and “N.Y. newspapers.” The rest of the writing in the notebook is in ink. The book contains 44 ruled pages, 19 of which have writing on them. On the front of the back flyleaf is the word “Eskimos” written in Peary’s hand. The book contains two sections. The first is titled “Statements of Panikpah, Itookishoo, Aukpillar” and the second “General Summary.” For context, I’ve reversed these sections in the transcription that follows:

General Summary [The page before the one this is written on has been torn out]

On our arrival at Etah in August 1908, we learnt that Dr. Cook had left Annoratok early in March with the following Eskimos, Panikpah, Egingwah, Aukpillar, Poodlunah, Inughito, Koolitingwah, Itookishoow & Aukpillar.

Later a letter was received from him dated Cape Thomas Hubbard was seen.

From Cape Hubbard the first 6 named Eskimos returned to the Greenland side and 2 boys one of whom had been with me on the ice in 1906 remained with Dr. Cook.

The men and experienced hunters who were in the party and who had returned from Cape Hubbard were asked why some of them had not remained with Dr. Cook instead. They said they did not have confidence in Dr. Cook in going on the ice.

When asked why the 2 boys remained with him they stated that perhaps they were very anxious for the things promised them and perhaps did not know any better.

During the winter at Cape Sheridan [in 1908-09] some of these men who were in my party repeated the above statements.

On our return from the north in August 1909, in our first contact

*****

with the natives August 8th at Nuekky we were told the following.

That Dr. Cook had returned this spring and had gone to Danish Greenland.

That he & his men had come back on foot having lost all their dogs; that they had spent most of their time absence to the southwest and had wintered in a locality which was at once located as Jones Sound; that they & Dr. Cook had wintered told the white men at Anoratok that he had been a long distance on the ice, but they had lied about it.

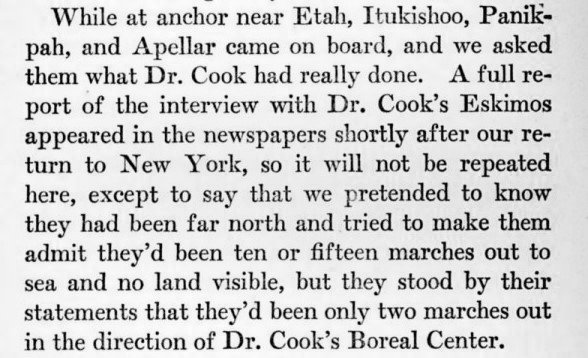

Arrived at Etah on the 14th of August the 2 boys who had been with Dr. Cook were asked about their experiences as was the father of Itookishoo [Panikpa] one of the older men and most experienced hunters of the tribe who is familiar with the Jones Sound region from his various hunting trips.

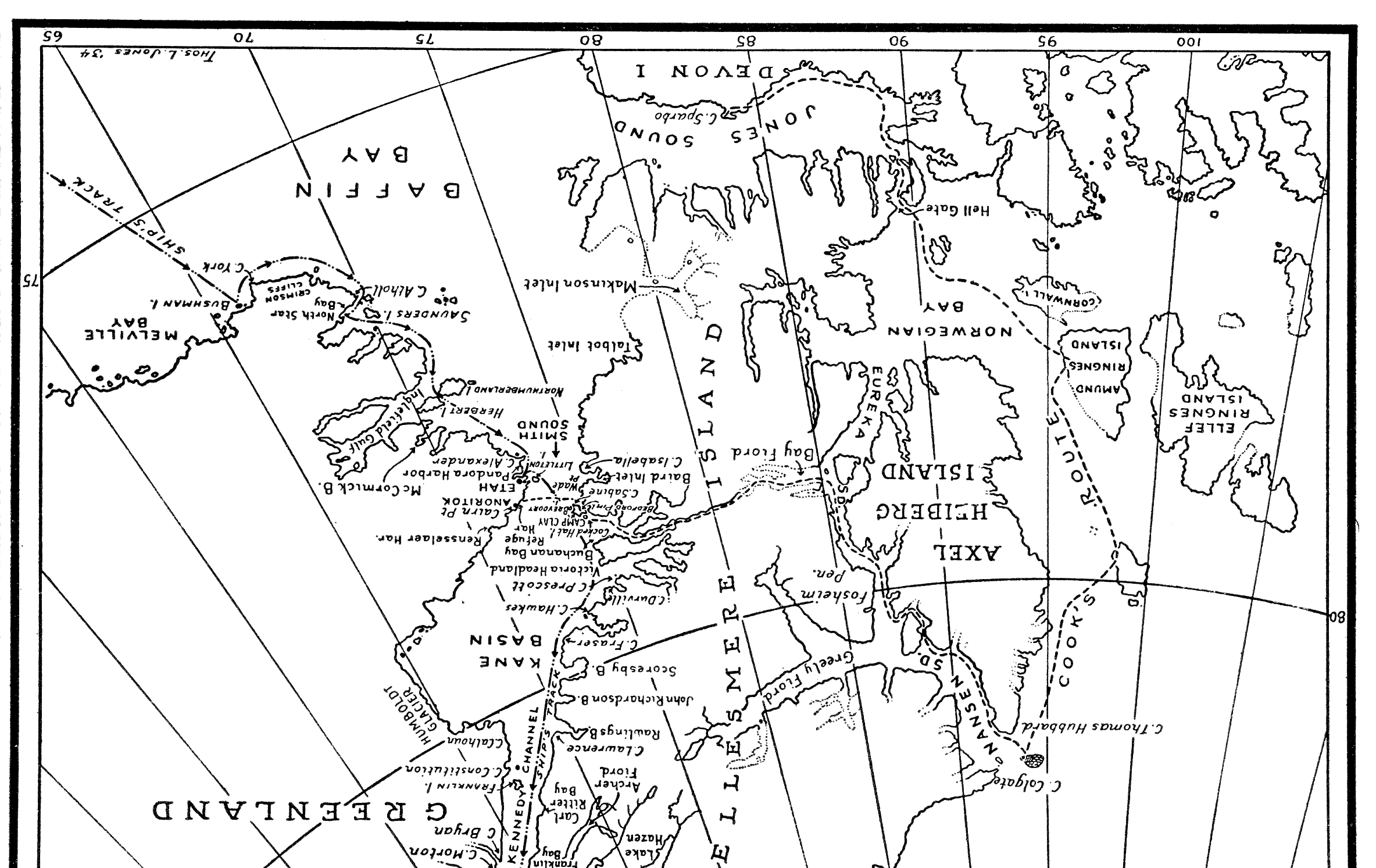

These 3 were questioned separately over Sverdrup’s map of his explorations

*****

and the stories of all 3 agreed.

These men were not threatened. They were given no presents to induce them to tell their story nor where they asked leading questions.

They stated that they had been instructed by Dr. Cook not to give me or any member of my party any particulars of the trip.

Omitting minor unessential details their story was as follows.

*****

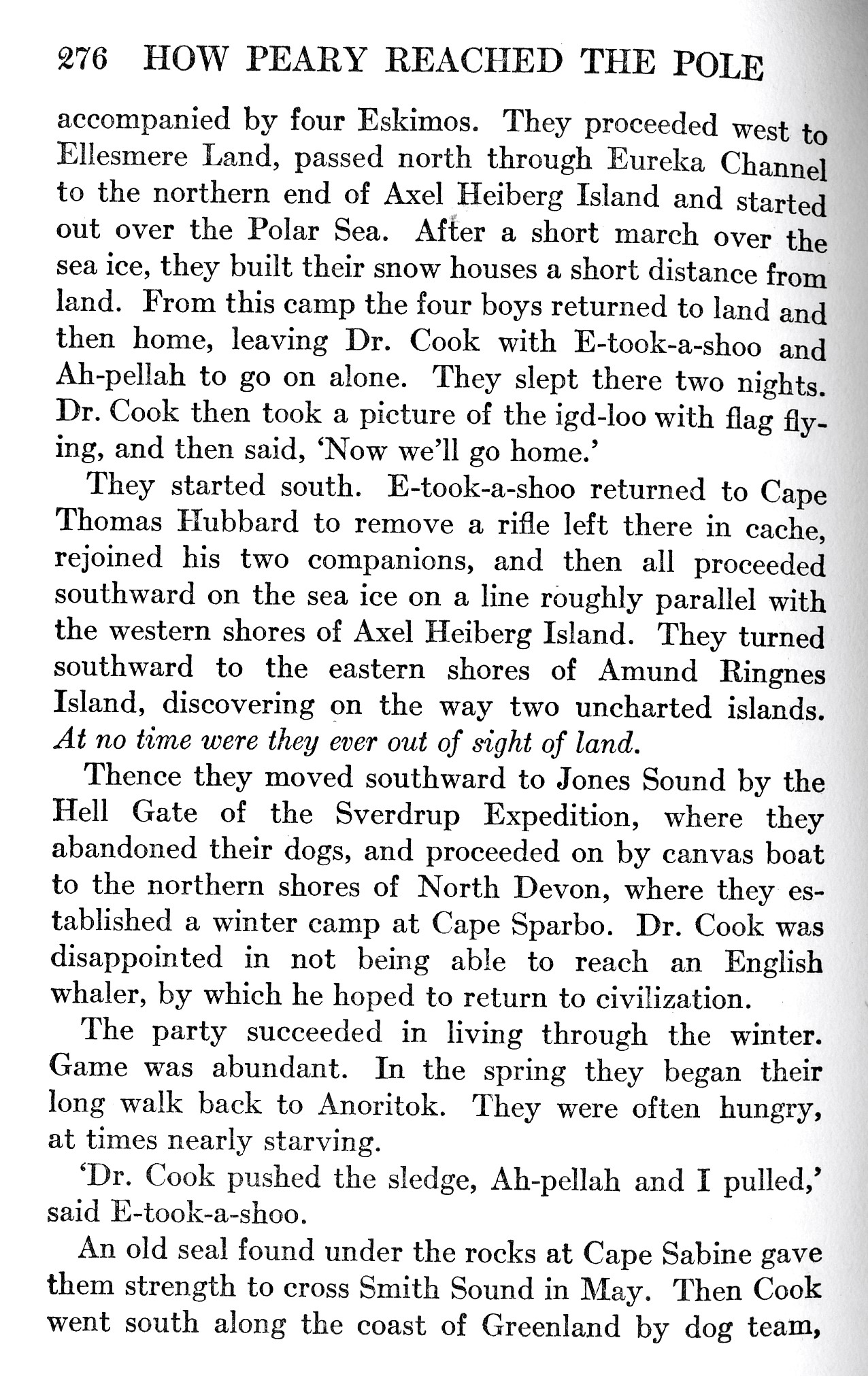

After the return of the other Eskimos they & Dr. Cook had gone north or northwesterly with 2 sledges & 21 dogs from the land (Cape Thomas Hubbard) for a short distance over the ice. They were at no time out of sight of the land from which they started nor did they see any other land.

They returned to land with both sledges with a large amount of supplies (the natives stating particularly their sledges were still heavy when they reached the land)

*****

They saw no bear upon the ice, they had no meat upon their sledges when they left the land. They killed none of their dogs on [the] ice to feed to the others, they made no caches on the ice. They crossed no leads.

They returned to the land from which they had started & Itookishoo got his rifle which he had cached on the land.

They then went down the west coast of Jesup Land. (Heidelbrug <sic> Land of Sverdrup) to the group of small islands shown on Sverdrup’s chart

*****

from whence they crossed the narrow southern end of of Crown Prince Gustav sea to Rignes Land, followed that across Norwegian Bay to Sverdrup’s Simmon’s Peninsular and Hell Gate. Here they abandoned their dogs took to the boat and followed around the head & south shore of Jones Sound, met ice on the inside of Coburg Bay Island; went back to Cape Sparbo where they wintered and then in the spring followed the coast north to Cape Sabine & thence across to Annoratok.

*****

Panikpah says the ice close to the land was good but as soon as the boys struck the rough ice beyond they & Cook returned.

Panikpah states that besides himself there were the following Eskimos. Poodullunah, Aukpillar, Aukpillar [two different Inuit with the same name] Egingwah, Inughito, Koolitingwah, Itookishoo.

4 of them returned back from the northern end of Nansen Strait i.e. Panikpah, Eqingwah, Poodullunah, Aukpillar.

Inughito & Koolitingwah went one short march on the ice, helped build

*****

igloo in a wind, did not sleep there, but returned to land. They caught the others [4 Inuit who had returned from Cape Thomas Hubbard] at Schei Island. On their return they killed one bears & musk oxen.

Aukpillar’s Statement.

Says they saw no land out on the sea ice.

“Dr. Cook Shag-la-hu-tee shu-tee shu-tee” [This translates roughly as “Dr. Cook is a big liar.”]

They only built 2 igloos on the ice.

They travelled up in Colin Archer Penn.

Points out Cape Sparbo at once as place there they wintered and Cape Clarence as where they killed a bear. [Illegible word]

Itookishoo stated

[Here is inserted on the upper blank page what appears to be an unrelated afterthought about Aukpillar’s testimony]:

Aukpillar said they met a lead of open water & turned back

This was at the edge of the glacial fringe.

[The interrupted narrative then continues:]

*****

the same thing.

Emphatically reiterates they did not go out of sight of land.

Aukpillar had 11 dogs

Itookishoo had 10 dogs.

Both boys say they saw cairn built by Peary. Cook says they did not see it it. Said Peary had never been there.

They landed a few miles west of where they started. And followed west coast of

Itookishoo as soon as they returned to land went after his gun which he had

***** [Here two pages have been torn out of the notebook]

which he had cached with provisions at Cape Hubbard.

Their sledges were still heavy when they returned to land. They took a few tins of pemmican from the cache to increase their loads.

At Cape Hubbard on their return they slept 5 times, the sun being warm enough to dry their cloths.

After leaving Cape Hubbard they only built 3 igloos then used their tent

******

Itook

Itookishoo says he did not see Crocker Land.

Landed Amundsen <sic> Rignes Land. Killed 2 deer there

Came inside Graham Island.

Went through Helvedesportent in their boat.

The dogs were abandoned at Lands End.

From Cape Hubbard they went Northwest slight westward drift.

They did not go out of sight of land.

A sample page from Borup’s notes

*****

Itookishoo who knows the sea ice from his experiences in Matt Ryan’s party says they did not go as far as Ryan went.

States that Cook said he went a long way but that he lied. They went for a short distance and made poor progress.

Many bear in Norwegian Bay.

Musk ox at Cape Sparbo.

1 bear killed at Cape Clarence. Nothing else secured for food till they reached Sabine where a seal cached by Panikpah the year before was secured. [An indeterminate number of pages have been torn out between the last intact page and the back flyleaf.]

The rest of the members of Peary’s crew left no statements or written records that have yet come to light. As one reporter characterized their mood upon the Roosevelt’s return to Labrador, “Speculation is rife over the possibility of a rebellion among certain members of the Roosevelt crew who were sworn to silence concerning Dr. Cook. ” He also noted that some of the men were “bearing themselves as men who had been badgered for weeks over that single issue of fact,” and then added: “There is no doubt of the fact that Peary exercises an almost savage dominance over the members of his expedition. He is a man of tremendous physical energies and said to have a volcanic temper.” [New York World September 21, 1909]

As for Peary himself, an indication of what he knew about Dr. Cook’s journey and when he knew it came at his first interview with dozens of reporters in Sydney. When asked if he had any comment on Pritchard’s “confession” that he had known for months of Cook’s claim to the pole, he said “Not the slightest” with a finality “that made some of the interviewers jump.” And when asked at what time he had first heard of Cook’s claim to have reached the North Pole, he began to answer, “I heard while at Etah that . . .”, but then, according to one reporter, cut himself short: “His jaws snapped together like a bear trap, and he flung himself back in the chair so that it creaked and rocked. Winking his eyelids and working his jaws for a moment, he said more softly than he had yet spoken: ‘I do not wish to say any more yet. Let us waive that.’” [New York World, September 22, 1909]

This indicates, like Henson’s statements, that Peary was aware that Cook’s two companions had initially said that Cook had told them they had reached the North Pole.

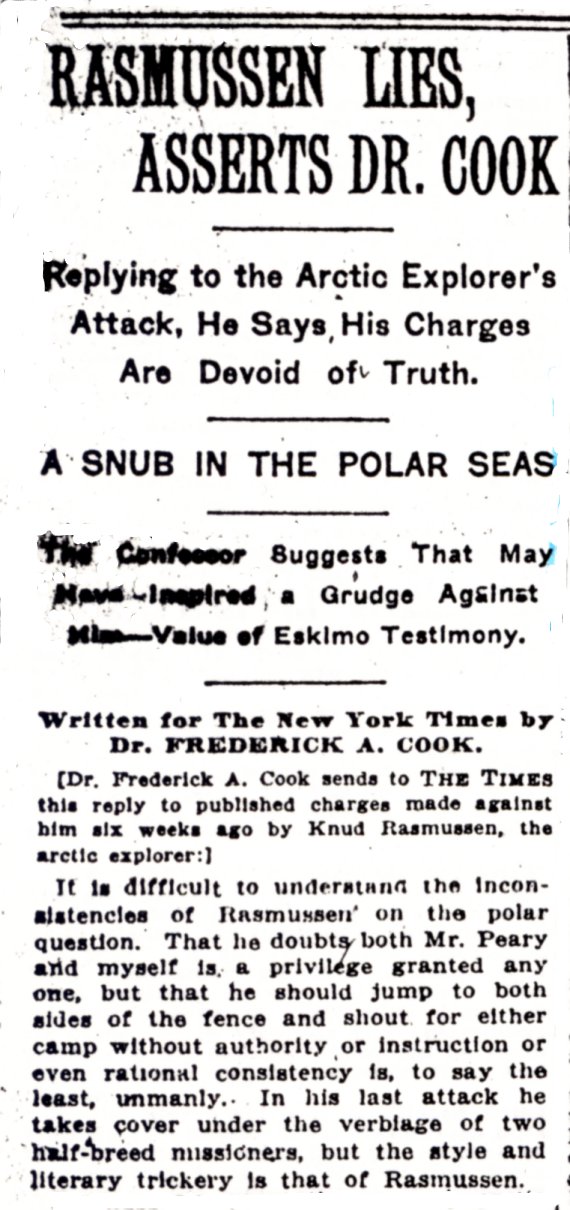

Harry Whitney

Harry Whitney confirmed this in an interview printed by the New York Times on September 29, 1909. Whitney, though not a part of Peary’s crew, was the one who first met Cook upon his return to Annoatok and who lived with him in Cook’s box house for the three days before he departed south. Whitney said he had spoken with Cook’s Inuit after Cook left for the Danish settlements and that they said they had been to the pole with Cook. As soon as the Roosevelt reached Etah, Whitney had boarded her but, acceding to the doctor’s request, stated to Peary that Cook had said he had gone beyond Peary’s Farthest North of 1906. Peary made no comment on this, but went straight to his cabin.

The next day Cook’s Inuit companions came to Whitney and asked him what Peary’s men were trying to get them to say. Peary’s men had shown them papers and maps, they said, but they did not understand these papers. When Whitney reached Newfoundland, he told reporters that he had heard nothing of Cook’s Eskimos retracting their statements to him or saying they never went out of sight of land, until he reached St. John’s. To the best of his knowledge, he said, Cook’s two companions never varied their story, though he admitted that Peary’s men could have gotten such a retraction without his knowledge.

It did not take long for Whitney to realize he had come down on the “wrong” side of the Polar Controversy, however. Peary thought Whitney had been lax as his “guest” and lacking in judgment and “gentlemanly feeling” to have had anything to do with his rival. Whitney was even personally chastised by General Hubbard, and bribed by Bob Bartlett with a prospective berth on Peary’s abortive Antarctic expedition to come over to the “right” side. By the time Whitney published his book, Hunting with the Eskimos, in 1910, he had. He recounted his meeting with Dr. Cook, but said not a word about what the Inuit had told him about their journey with him. That same year he accompanied Bob Bartlett to Etah where the records and instruments Whitney had been entrusted with by Cook to return safely to America, but which Peary had refused to transport on the Roosevelt, were apparently dug up from the cache where he and Bob Bartlett had buried them in August 1909 and disposed of.

That leaves Donald MacMillan. MacMillan had so much to say on the Inuit testimony that we must reserve a discussion of it for the next post.

Sources: Goodsell’s original diary is at the Mercer County Historical Society, Mercer, PA, as his unpublished manuscript of “There and Back Again.” A typed copy of Goodsell’s diary is in NARA II, College Park, MD, Record Group XP; Borup’s notebook is also at NARA II. The diaries of Thomas Dedrick and Josephine Peary referred to here are also at NARA II.

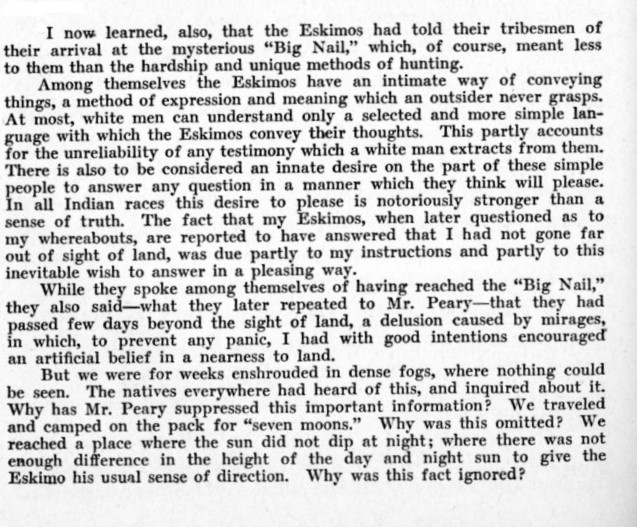

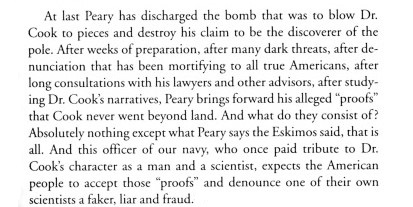

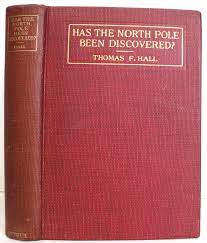

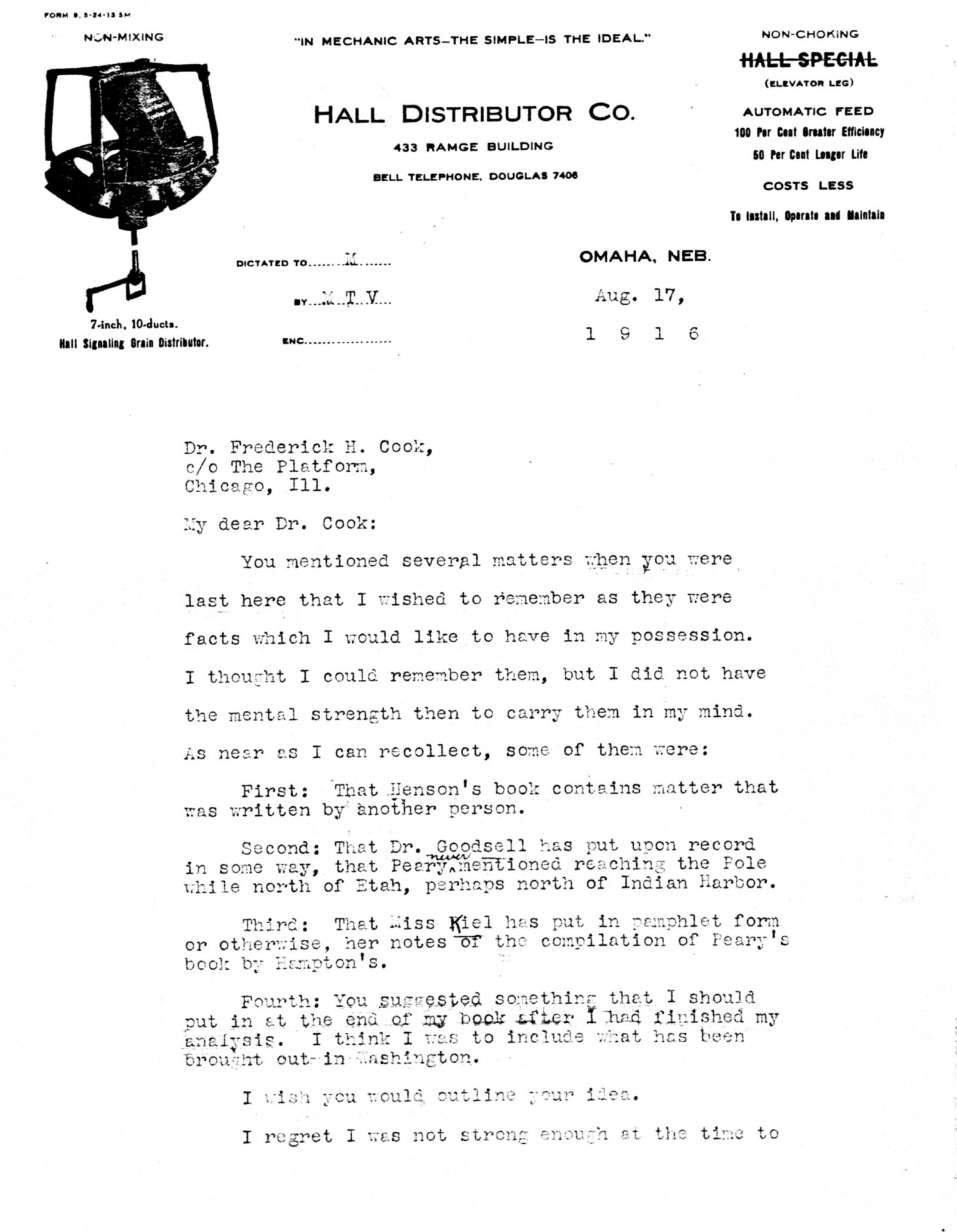

Hall takes up the “Eskimo Testimony” in his chapter entitled “How Peary Discredited Cook.” For anyone but a devotee of the subject, Has the North Pole been Discovered? is a laborious read, with it’s numerous rhetorical questions, repetitive digressions and involved theoretical suppositions. But for those willing to wade through its acres of rhetoric, it does contain a number of salient points on the topic at hand.

Hall takes up the “Eskimo Testimony” in his chapter entitled “How Peary Discredited Cook.” For anyone but a devotee of the subject, Has the North Pole been Discovered? is a laborious read, with it’s numerous rhetorical questions, repetitive digressions and involved theoretical suppositions. But for those willing to wade through its acres of rhetoric, it does contain a number of salient points on the topic at hand.

Members of the Swiss expedition: August Stolberg is at the far right, de Quervain is standing next to him

Members of the Swiss expedition: August Stolberg is at the far right, de Quervain is standing next to him