The Cook-Peary Files: The “Eskimo Testimony”: Part 1: Background and Prefigurement

October 12, 2022

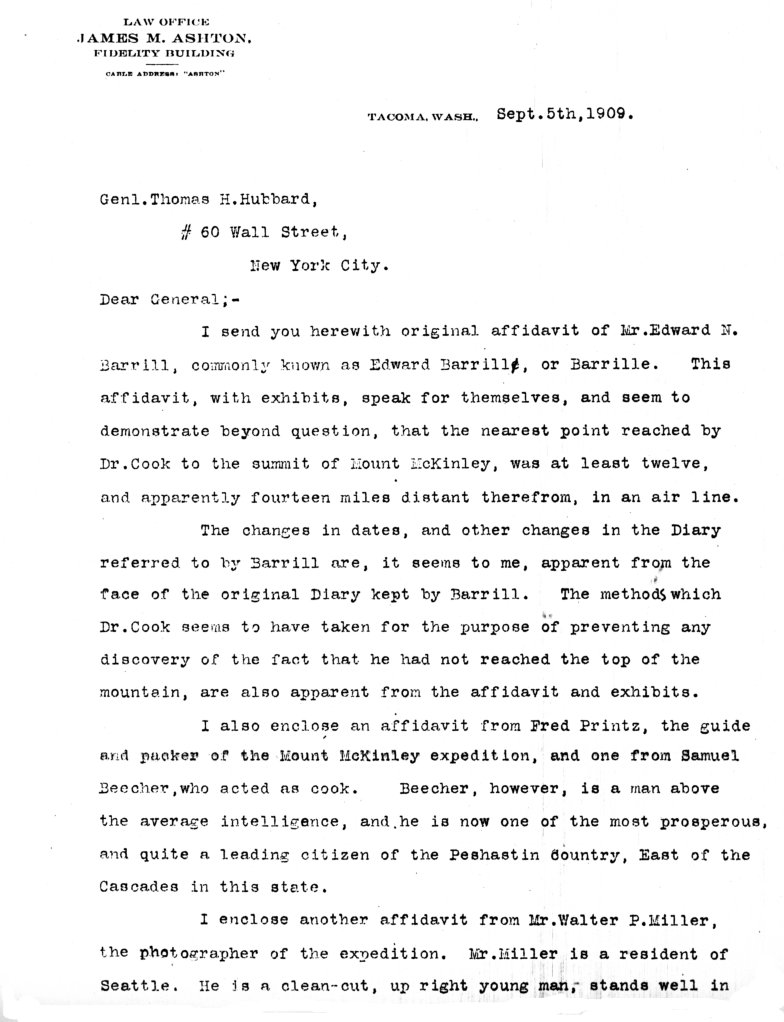

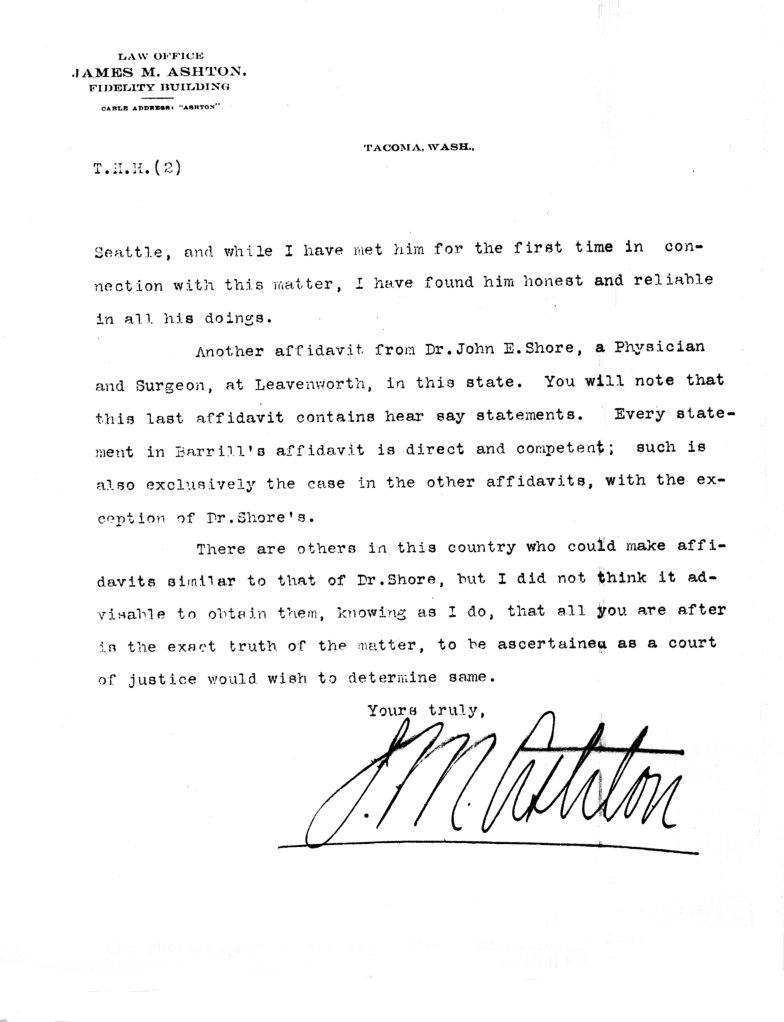

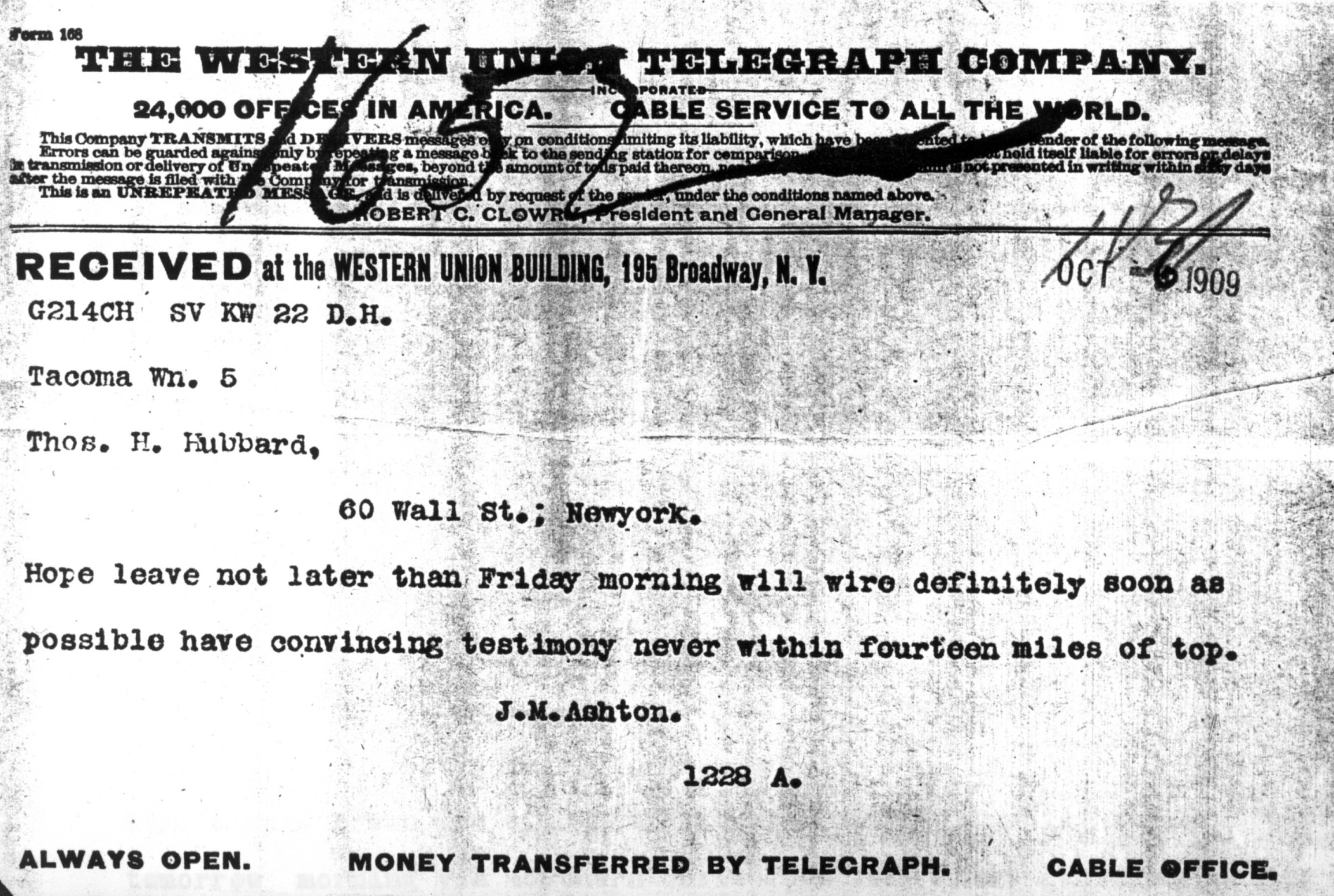

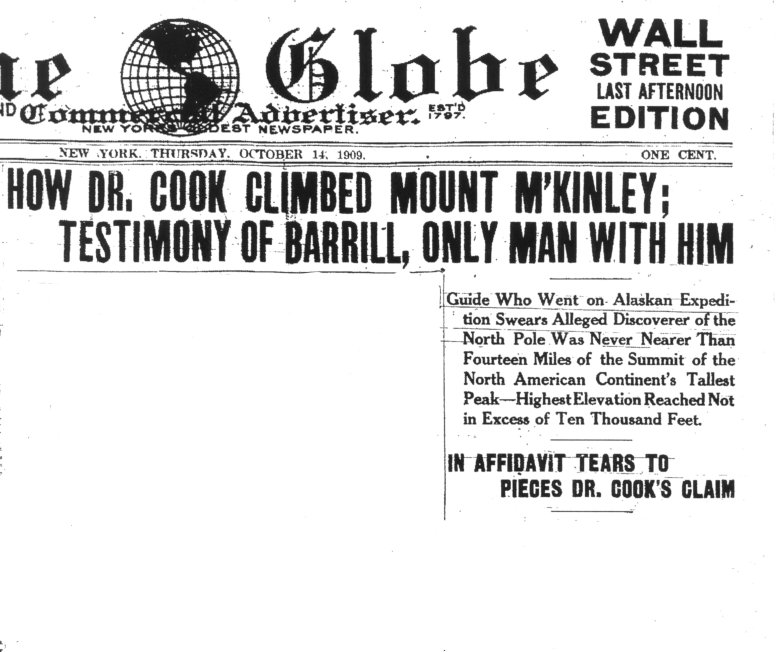

This is the latest in a series of posts that publish for the first time significant documents related to the Polar Controversy.

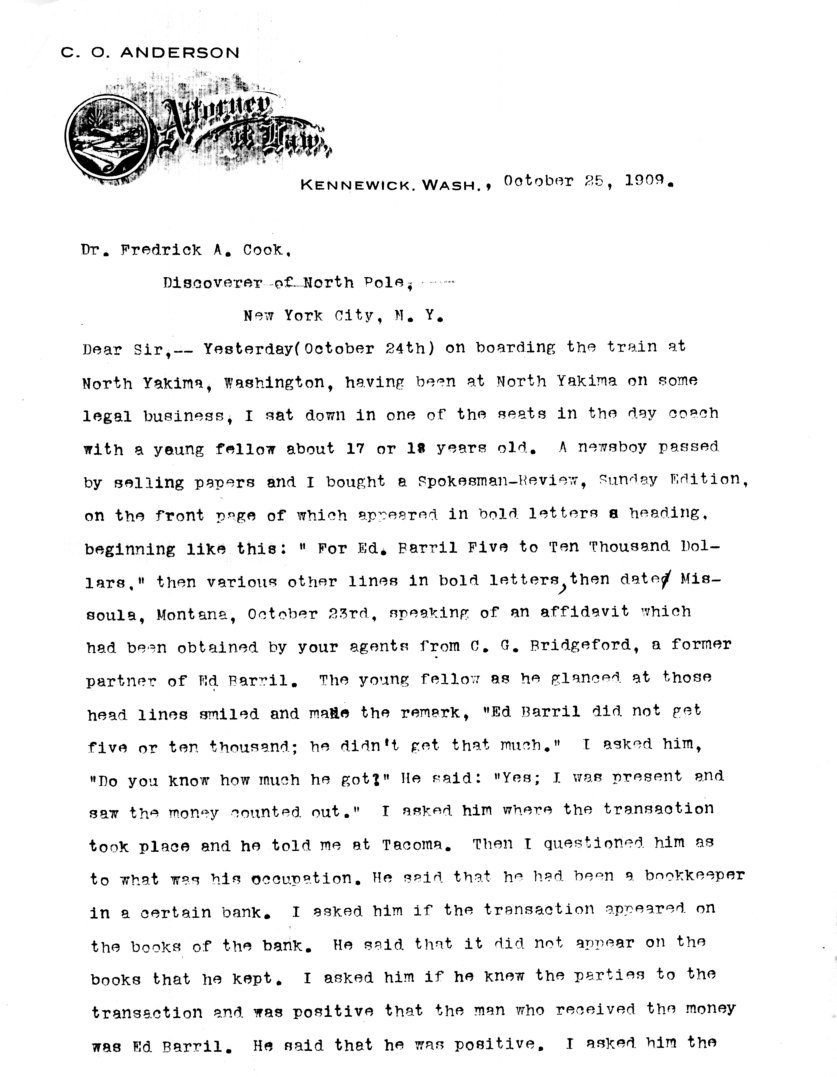

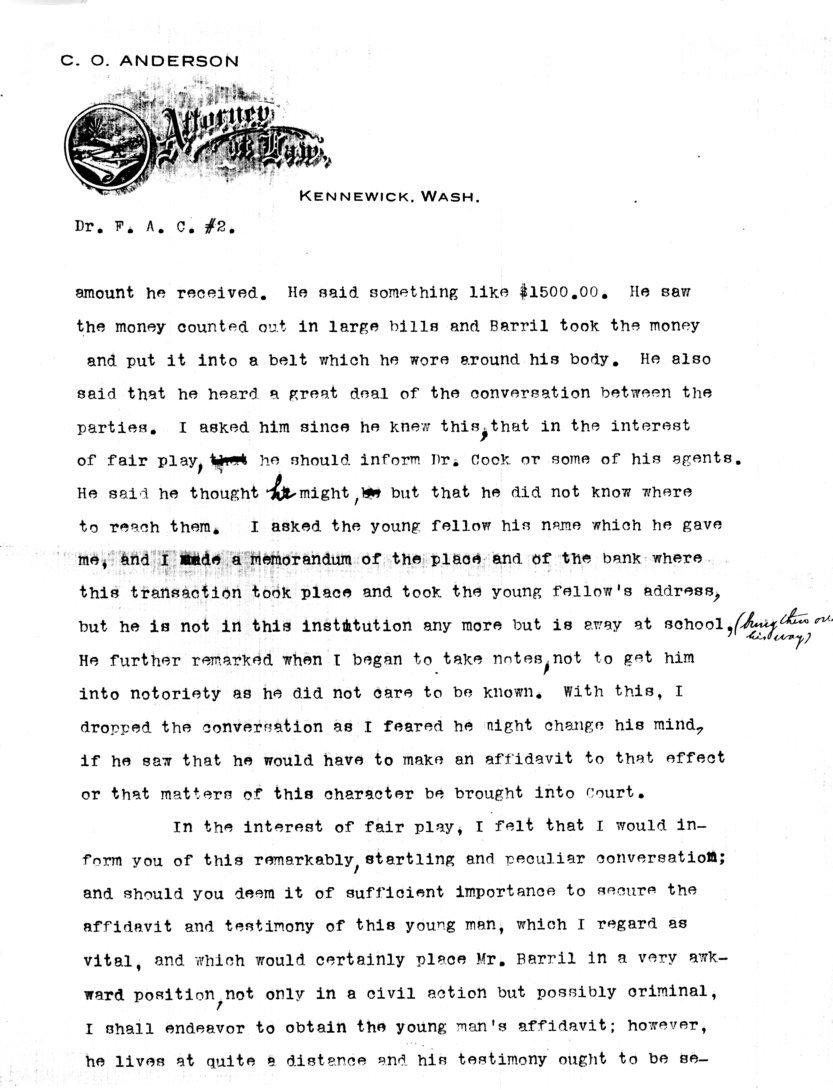

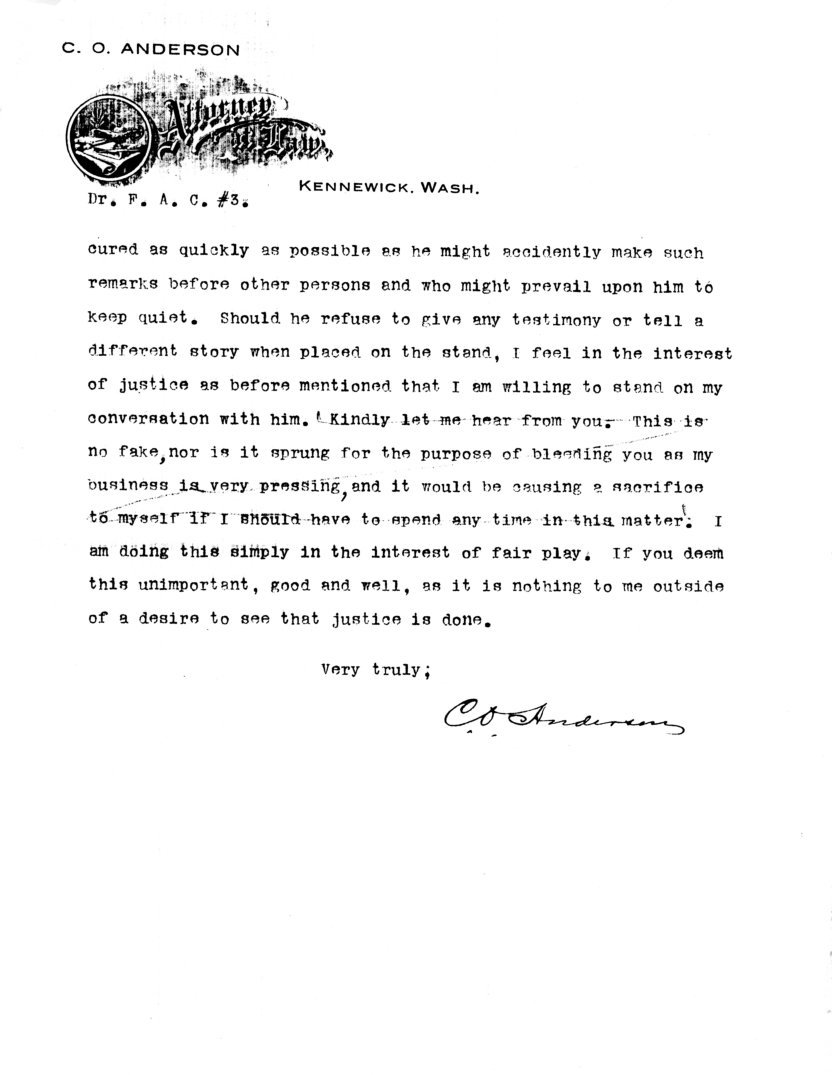

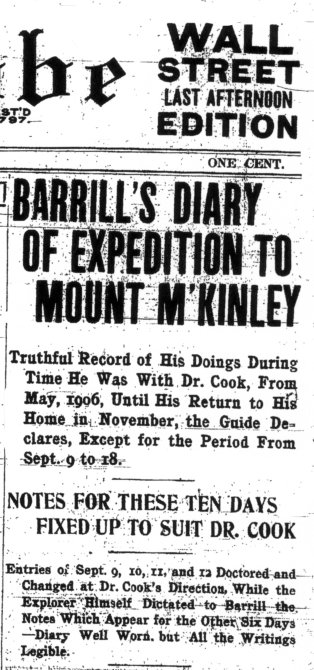

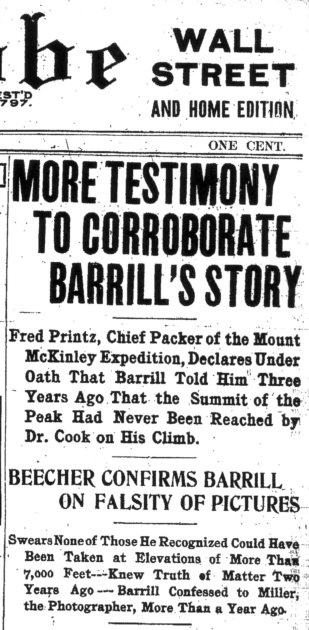

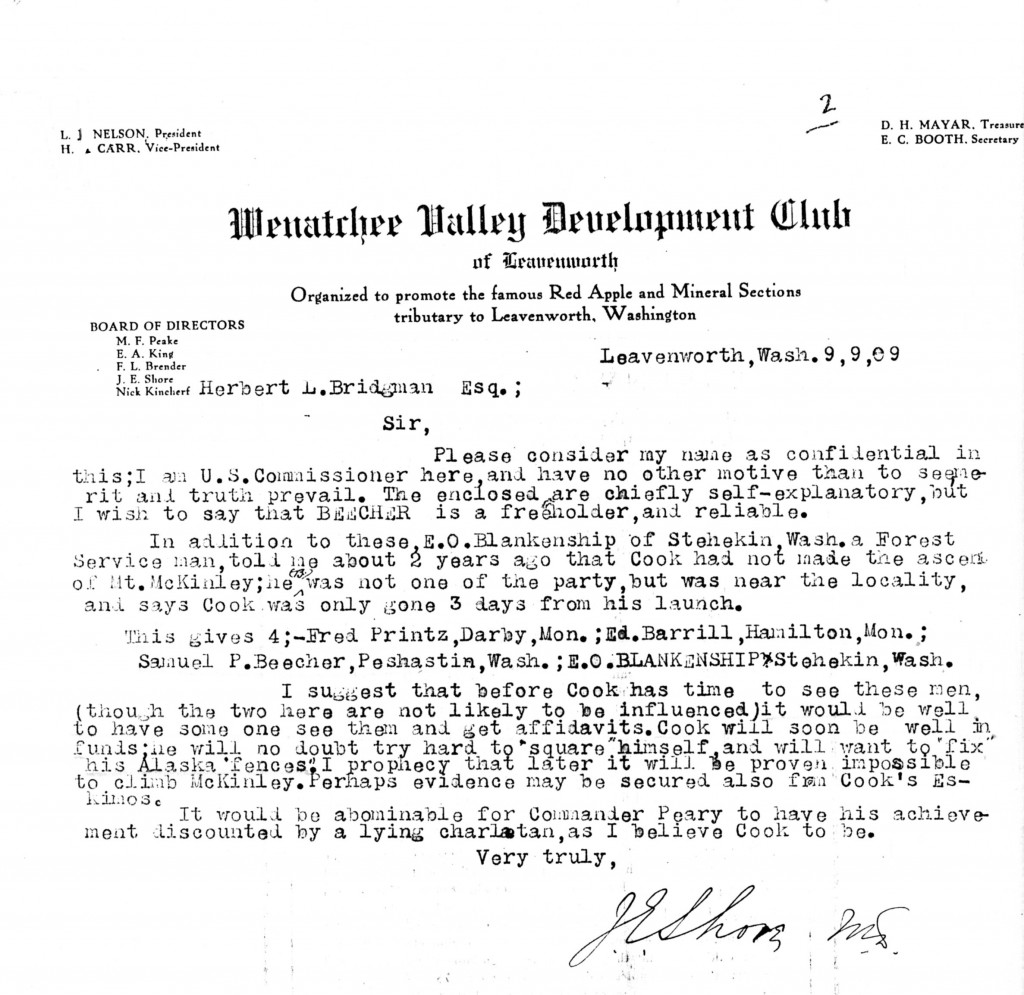

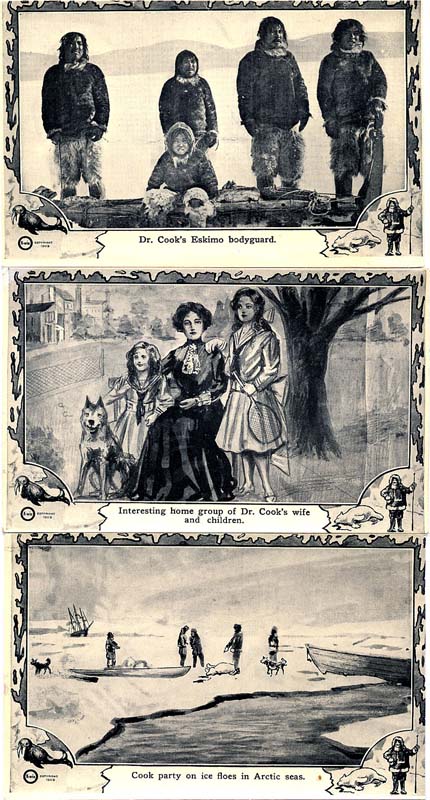

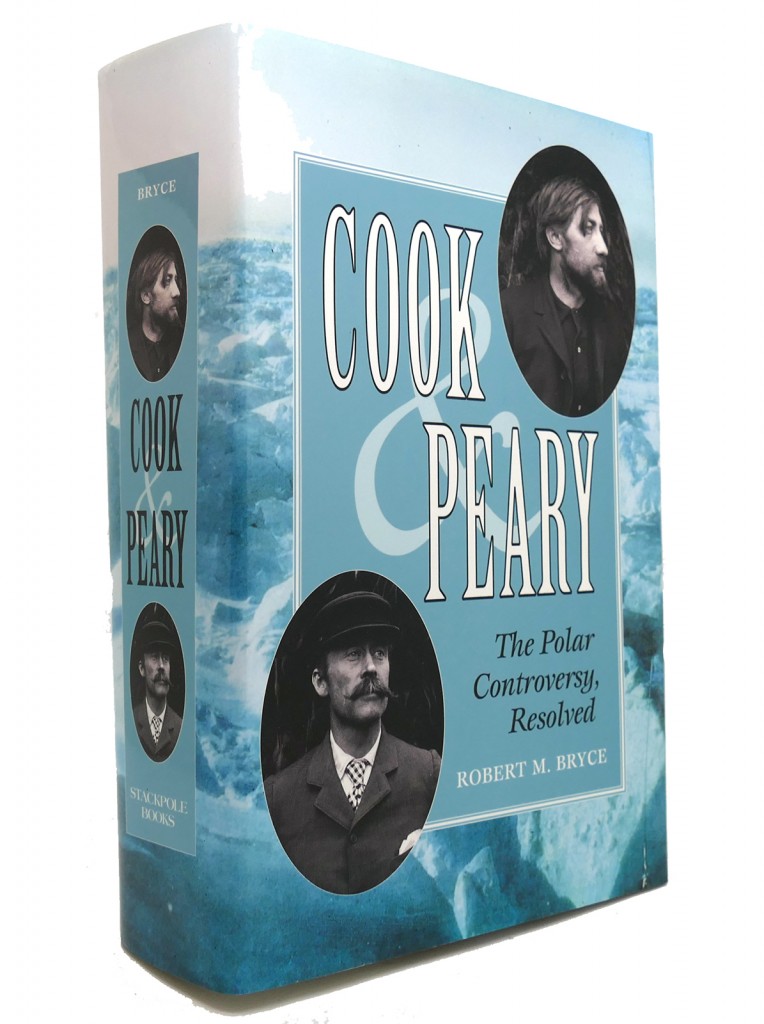

Among aficionados of the Polar Controversy, perhaps no single aspect has raised more debate than the truth and value of the testimony Peary allegedly obtained from Cook’s only two eyewitnesses to where he went after he left land on his purported trip to the North Pole. To evaluate this so-called “Eskimo Testimony” properly requires a highly involved process of analyzing a large number of statements made by various parties, some eyewitnesses, some with only hearsay evidence, that bear upon the statement published by The Peary Arctic Club in a copyrighted story that appeared on October 13, 1909 in papers served by the Associated Press. In this post we will examine the events that give background and context to the publication of Peary’s “proof” against Cook’s claim to have beaten him the North Pole.

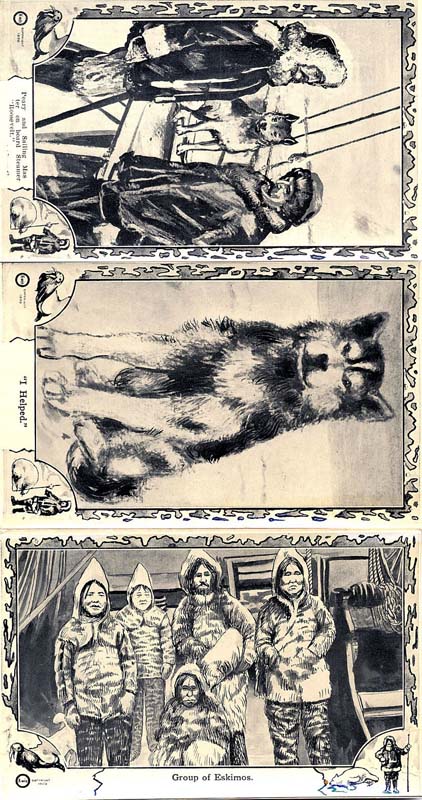

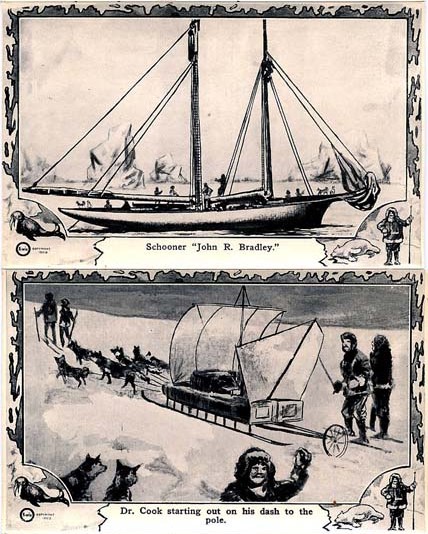

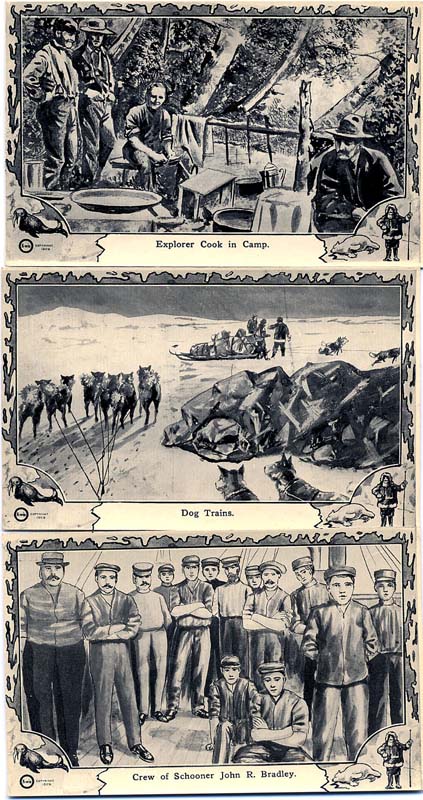

When John R. Bradley’s “hunting trip” to Greenland got back to New York in October 1907, he posted letters written by Dr. Cook in August. One was marked for delivery to the Secretary of the Explorers Club, Henry Walsh. In it Cook explained why he had not returned with Bradley: “I find that I have here a good opportunity to try for the North Pole and therefore I will stay here for a year. I hope to get to the Explorers Club in Sept of 1908 with the record of the Pole.” A similar letter was received by Herbert L. Bridgman, Secretary of the Peary Arctic Club, a wealthy group of backers who had bankrolled Peary’s attempts to reach the Pole for a decade. When he read the letter, Bridgman called Bob Bartlett, who passed the word along to Peary. When Peary got the news, it set him off on a letter writing campaign of his own.

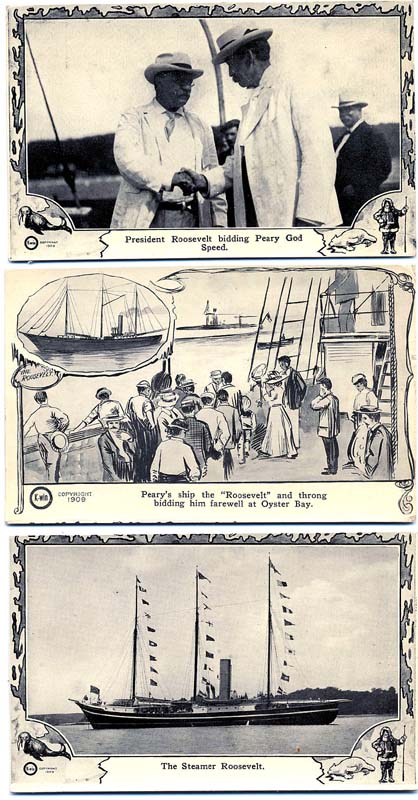

Peary had planned to begin another attempt on the North Pole that summer, himself, but when his chief backer and president of The Peary Arctic Club, Morris K. Jesup, suddenly died, Peary was unable to raise the immense sum of money he needed to repair the severe damage the Roosevelt had suffered on his 1905-1906 expedition. It soon became clear he wouldn’t be able to go north again until the summer of 1908, and if Cook returned when he told Walsh he would and with what he said he hoped, Peary would be in the Arctic and powerless to respond. Typical of the content of Peary’s letters was one to the International Polar Commission in Belgium, which said in part, “If Dr. Cook returns and claims to have reached the Pole, he should be compelled to prove it.” And since Cook was the sitting president of the Explorers Club, when Peary was offered that position in his absence, Peary only agreed to take the presidency if the Club adhered to the exact same demand.

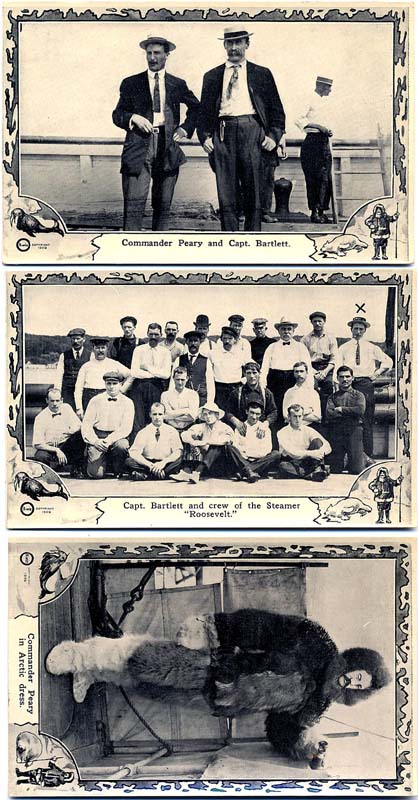

When Peary’s belated expedition reached Etah, the Inuit’s farthest northern village, in August 1908, he soon encountered Cook’s only white companion, a young German named Rudolph Franke, whom Cook paid to stay with him over the winter of 1907-08. From him and a letter written by Cook that Franke had received from Cook dated the previous March, Peary learned that Cook had reached Cape Thomas Hubbard, near the tip of Axel Heiberg Island, and had set out from there for the Pole.

Before he left for his winter base, Peary dictated letters to his private secretary, Ross Marvin, to be returned to New York by his supply ship, Erik, about “the Cook Affair.” To gain further details of Cook’s doings, before sailing, he took aboard his ship several of the Inuit who had accompanied Cook to Axel Heiberg and had returned from there, leaving him and just two Inuit, Etukishuk and Ahwelah. Among these was Koolootingwah, who had been with Peary when he reached Cape Thomas Hubbard in the summer of 1906.

As an emergency base of supplies to fall back on in case of accident to his ship, Peary took over the boxhouse where Cook and Franke had spent the winter at Annoatok, 25 miles northeast of Etah, and put his bo’sun, John Murphy, in charge of Cook’s supplies that it contained. He also left his cabin boy, Billy Pritchard, there to keep the log, as Murphy was illiterate. A young sportsman named Harry Whitney, who had come north with Peary for a fee of $500, elected to stay the winter at Annoatok as well (see the series of posts “Inside the Peary Expedition” starting in June 2020 for more details).

These three were on hand when Cook and his companions unexpectedly reappeared at their winter base on April 15, 1909. They had spent the winter on Devon Island and were so unkempt that Whitney did not even recognize Cook as a white man until he spoke to him in English. Soon after arriving, Cook told Whitney in confidence that he had reached the North Pole, but asked him not to tell Peary or any of his crew. Instead, he asked Whitney to say only that Cook had been farther north than Peary had in 1906, when Peary claimed to have beaten the Italian record for “Farthest North.” Billy Pritchard, who overheard Cook’s conversation with Whitney, was also sworn to silence, but Peary’s boatswain, John Murphy, was in Etah at the time, and was not let in on Cook’s confidence.

In My Attainment of the Pole, Cook wrote that he had given his two Inuit companions the same rejoinder: they were to say they had gone farther north than Peary in 1906, but not to mention his polar attainment. But Inuit could never keep a secret, and soon news that Cook had reached “the Big Navel” started to spread through the native settlements.

The world did not receive word of Cook’s accomplishment until September 1, 1909, when he wired the news from the Shetland Islands that he had reached the North Pole on April 21, 1908. Cook’s preliminary summary of his attainment was published in the New York Herald the next day. At that time, nothing had been heard from Peary, who was then already on his way home, but who had not yet reached the nearest telegraph office, located at Indian Harbour, Labrador.

On receiving word of Cook’s claim, Herbert Bridgman, heeding Peary’s demands for proof of his rival’s claim, suggested how that might be obtained: “The word of the Eskimos who went with him will be of use in getting at the proof,” he said. “The Eskimos cannot write, but Mr. Peary has told me that they can draw a map of the north pole and the regions surrounding that is remarkable for its accuracy. With this skill, the Eskimos ought to be in position to help Dr. Cook establish beyond doubt his claim.” (New York Times, September 3, 1909).

After Dr. Cook arrived in Copenhagen the next day, he seemed to agree: “An esquimau is a better judge of Arctic conditions and Arctic travel than a white man, and there is no real reason why as witnesses the word of Etukishuk and Ahwelah will not be quite as acceptable to the scientific world as that of any white man.” (New York World, September 5, 1909).

On September 6th Bridgman received a coded telegram from Indian Harbour announcing Peary’s own success. The next day Bridgman gave another interview to the New York Times in which he elaborated on his previous remarks: “I think, when Mr. Peary gives to the world his account of the stories told by the two Eskimo boys who accompanied Dr. Cook their narrations will do much to prove or disprove Dr. Cook’s claim. They are a simple minded people but they have a strange and wonderful intelligence regarding geography.” (New York Times, September 8, 1909).

Peary confirmed this line of attack on Cook’s credibility in a telegram dated September 8: “Cook’s story should not be taken too seriously. The Eskimos who accompanied him say that he went no distance north. He did not get out of sight of land. Other men of the tribe corroborate their statements.” (New York Times, September 9, 1909.)

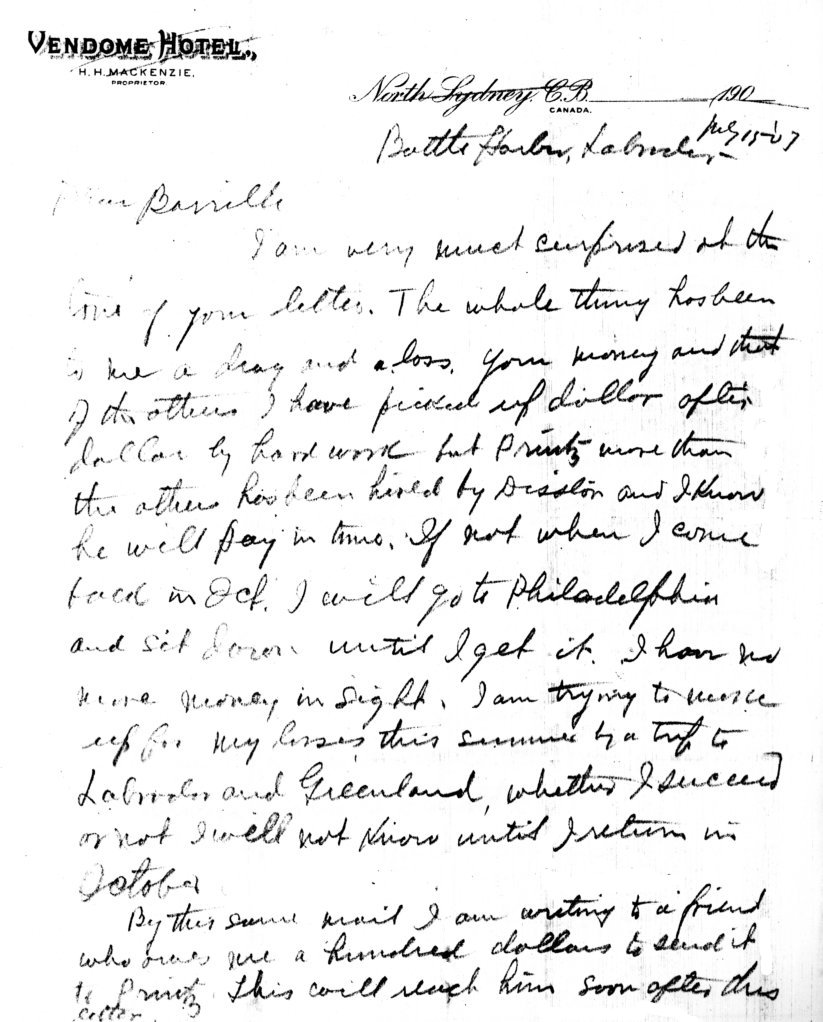

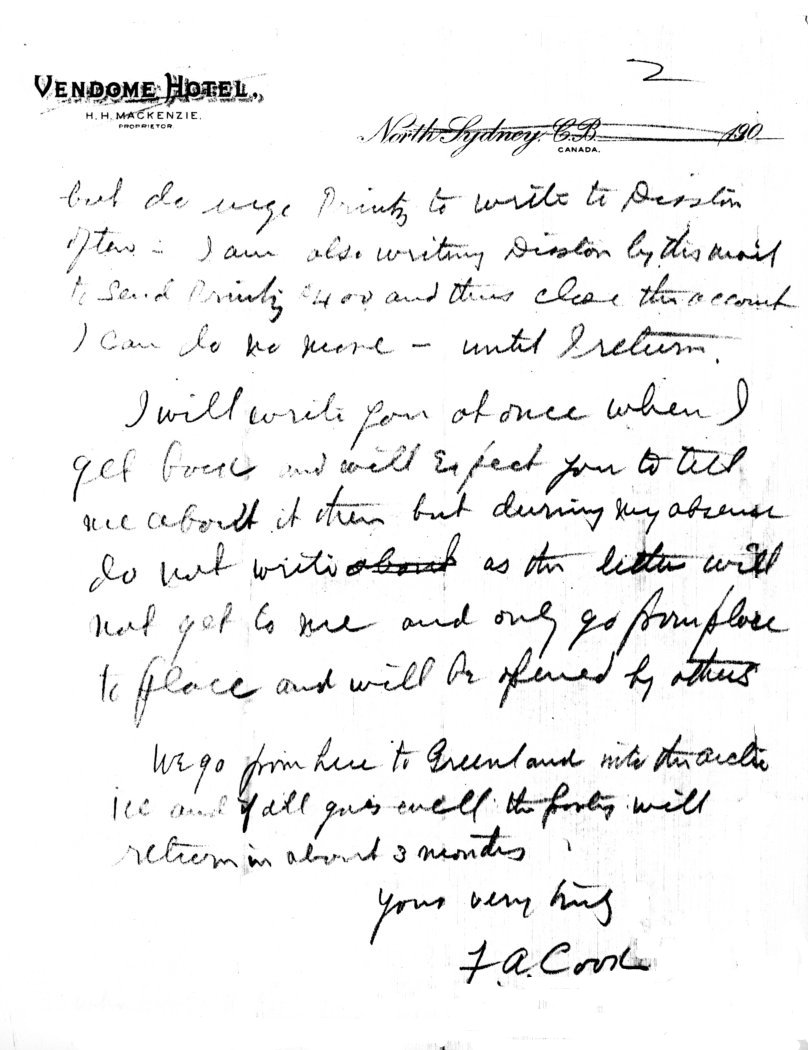

By then, Peary had moved down the Labrador coast to Battle Harbour, where he lingered for more than a week, all the while sending and receiving telegrams by the score, including, finally, the exclusive account of his own polar journey to the New York Times. Upon reading it, many noticed a remarkable similarity to the preliminary report of Dr. Cook, sent a week before. But of course, Cook claimed to have been to the pole nearly a year before Peary. If Peary was to achieve his long-cherished ambition of being The Discoverer of the North Pole, then Cook’s claim had to be convincingly demolished.

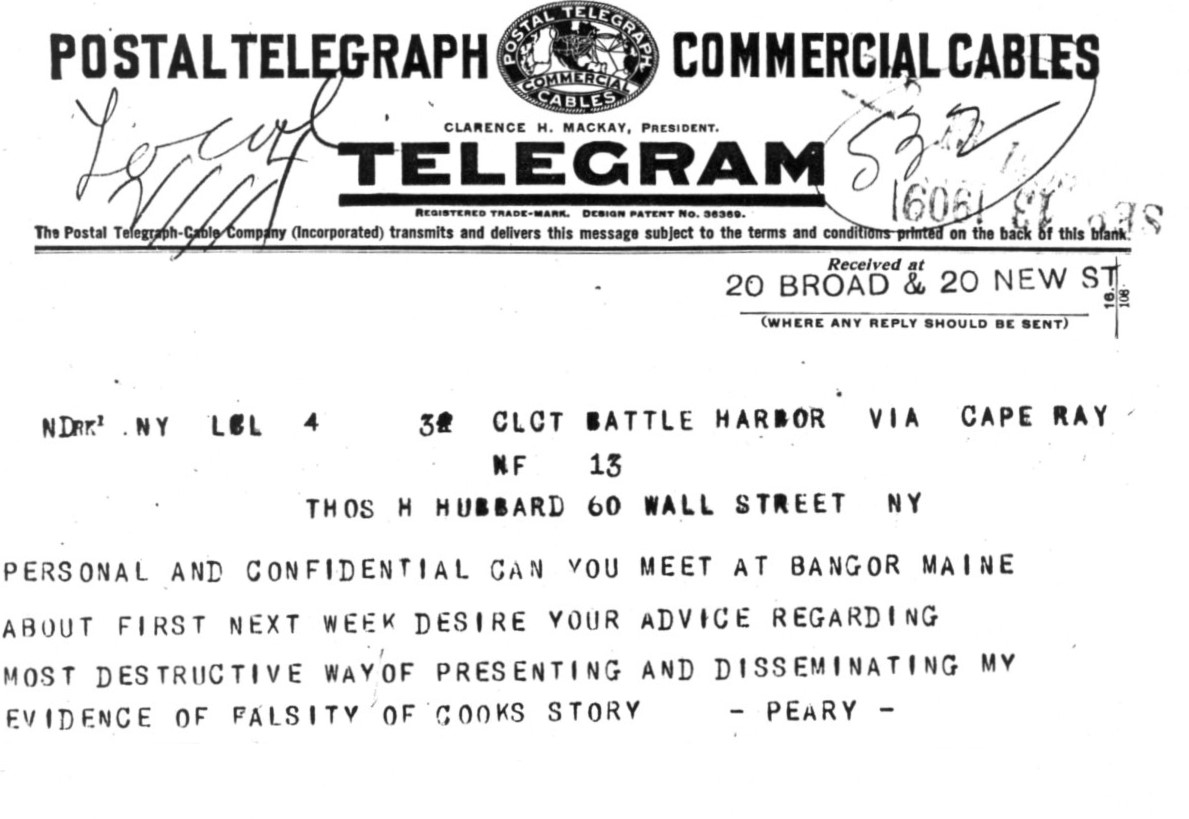

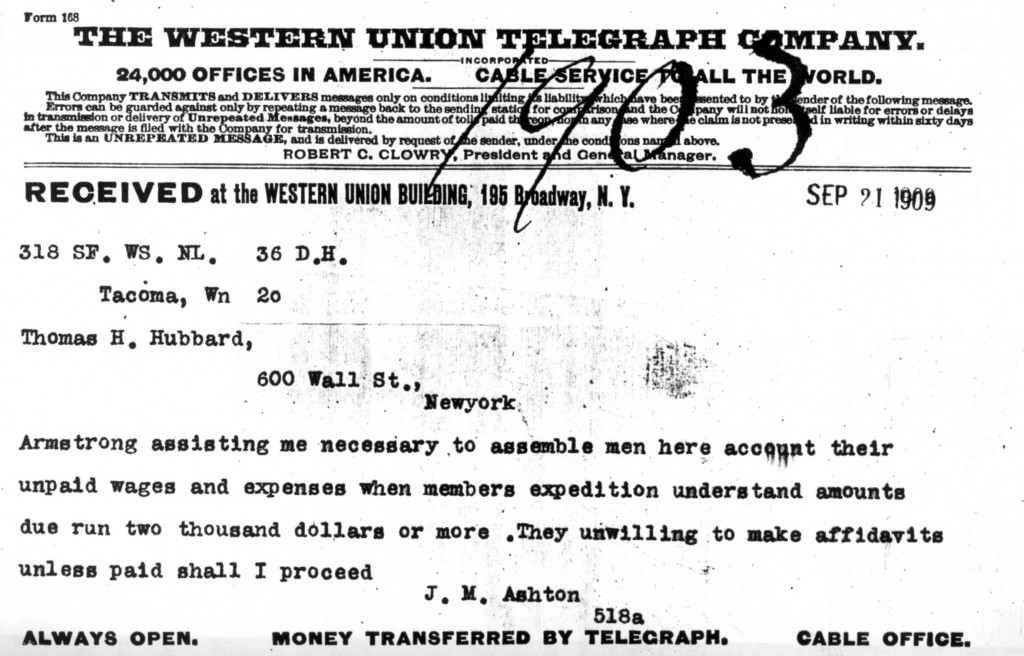

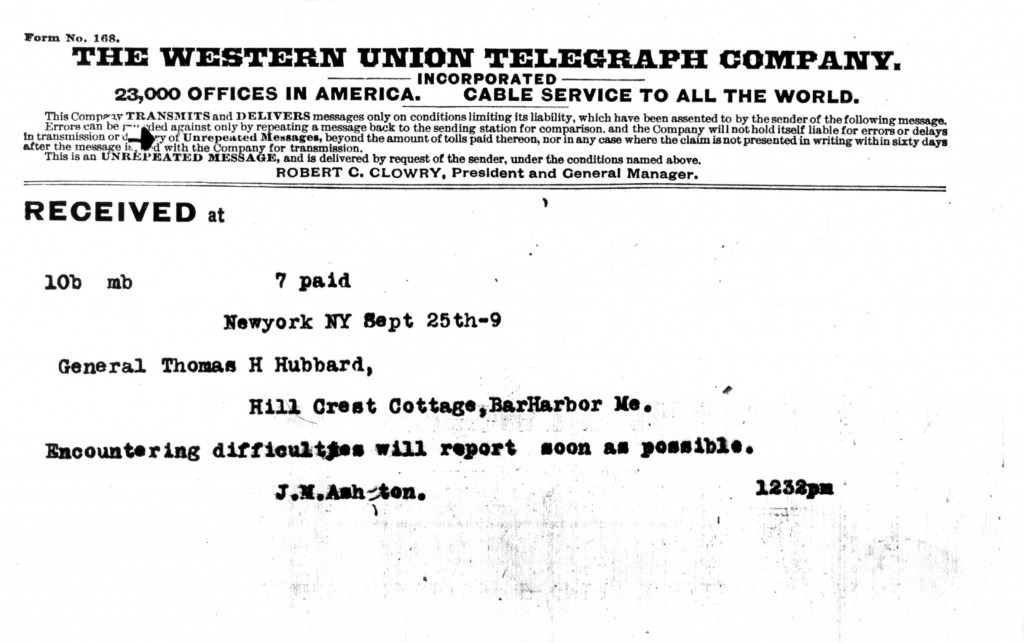

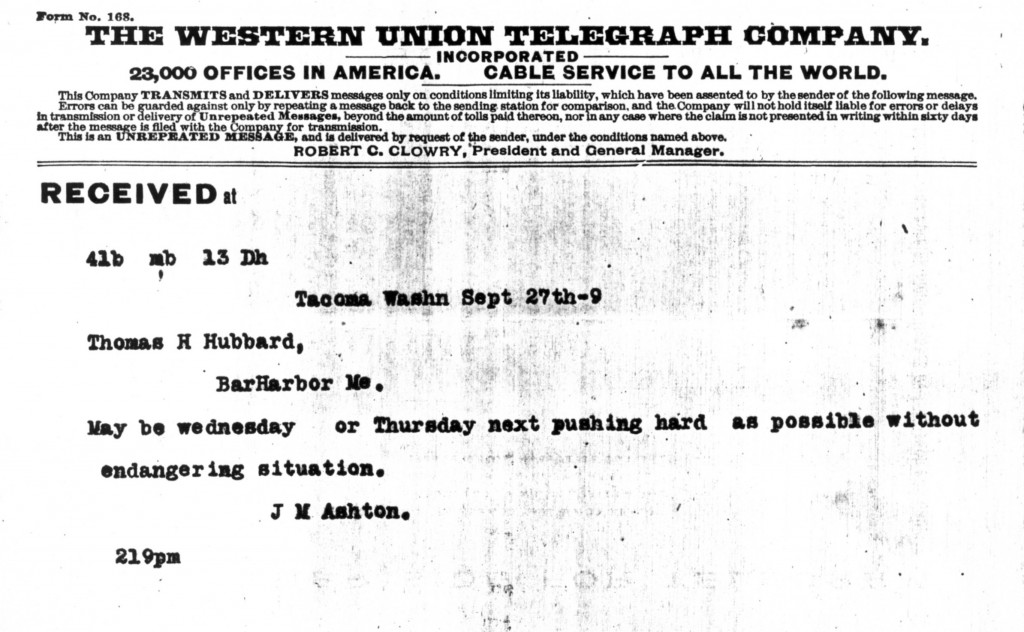

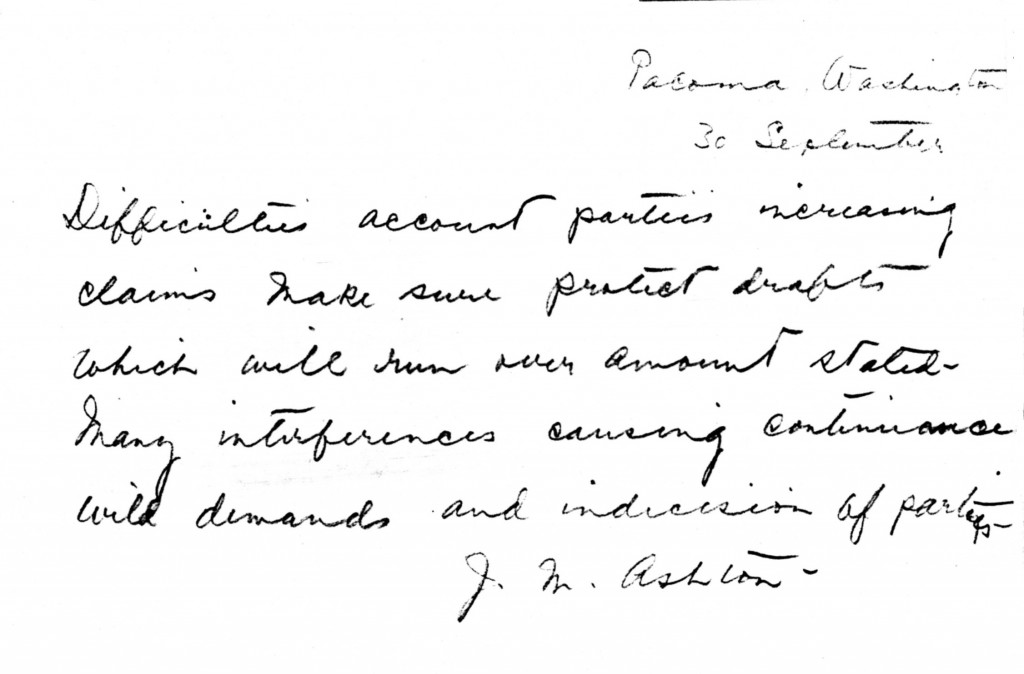

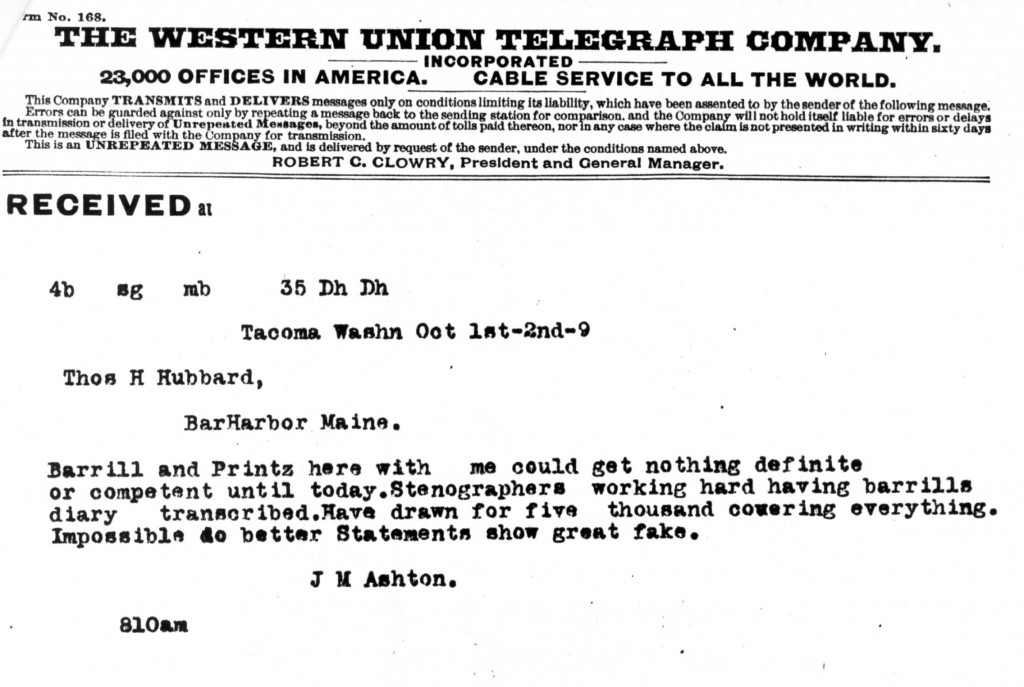

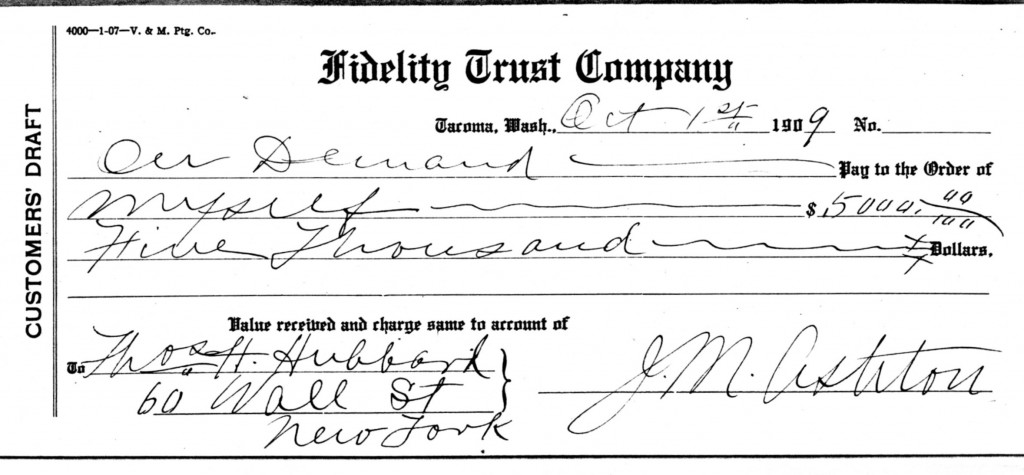

On September 13th Peary wired Thomas H. Hubbard, who had succeeded Jesup as president of the Peary Arctic Club:

The telegram is among the Peary papers at NARA II in College Park, MD.

[“Armstrong” was William Armstrong, one who assisted Cook with his 1906 pack train.]

[“Armstrong” was William Armstrong, one who assisted Cook with his 1906 pack train.]

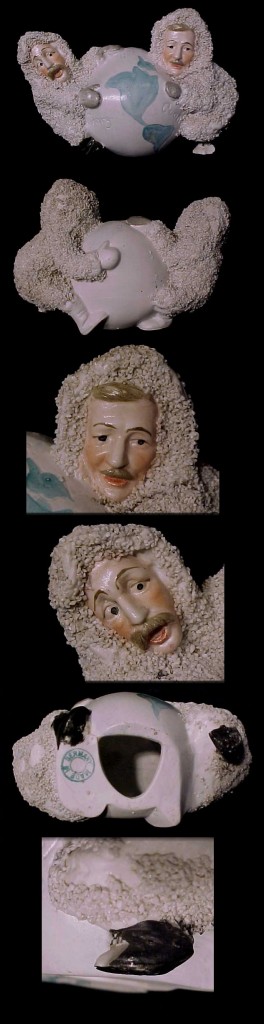

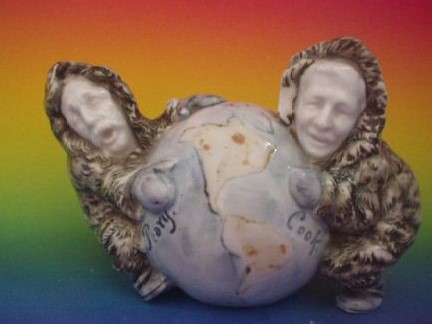

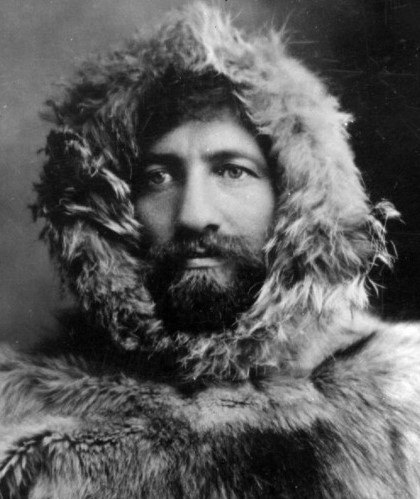

It shows him in a fur outfit, fully bearded. The mug shows his right, mitted hand holding a pair of binoculars. At its bottom it has “COOK’ inscribed in block letters.

It shows him in a fur outfit, fully bearded. The mug shows his right, mitted hand holding a pair of binoculars. At its bottom it has “COOK’ inscribed in block letters.

He has a small pouch strapped across him which he is clutching with his left hand, and a curved brown object in his pocket. Just what this object is supposed to represent is not obvious. “PEARY” is inscribed at the bottom.

He has a small pouch strapped across him which he is clutching with his left hand, and a curved brown object in his pocket. Just what this object is supposed to represent is not obvious. “PEARY” is inscribed at the bottom.